Kraków

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Kraków (disambiguation).

Kraków (Polish: Kraków [![]()

![]() ˈkrakuf]), the capital of the Lesser Poland Voivodeship, is located in southern Poland about 250 km southwest of Warsaw and is the country's second-largest city, with a population of about 775,000.

ˈkrakuf]), the capital of the Lesser Poland Voivodeship, is located in southern Poland about 250 km southwest of Warsaw and is the country's second-largest city, with a population of about 775,000.

The independent city on the upper Vistula was the capital of the Kingdom of Poland until 1596, is home to the second oldest university in Central Europe after Prague, and has developed into an industrial, scientific and cultural centre. Numerous buildings from the Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque and later periods of art history characterize the cityscape. Even in the 21st century, Krakow is still referred to as the "secret capital of Poland" and is considered the "centuries-old centre of Polish statehood". This is also evident in the former residence on Wawel Hill with the castle and cathedral, where most of Poland's kings are buried, as well as numerous personalities of outstanding historical importance.

Today, Krakow is a vibrant technology and life sciences hub for Central and Eastern Europe and the second largest office market in Poland after Warsaw. Krakow is also a major cultural, artistic and scientific hub, with, for example, the headquarters of the National Centre for Science (Polish: Narodowe Centrum Nauki), the Centre of the Knowledge and Innovation Community and the EIT. One of the most important film studios in Central Europe is located near Kraków. According to the 2011 World Investment Report of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Krakow is the most emerging location for investment in innovation in the world. About eight million people live within a 100 km radius.

In 2000, Krakow was the European Capital of Culture. Krakow was one of the venues for the 2014 Men's Volleyball World Cup and the 2016 European Handball Championships. Krakow was also European City of Sport in 2014. In 2016, Krakow hosted the World Youth Day of the Catholic Church.

Main Market Square (Rynek Główny) with the Cloth Halls, Wawel, Barbican, St. Mary's Church, St. Peter and Paul, Collegium Maius

Geography

City breakdown

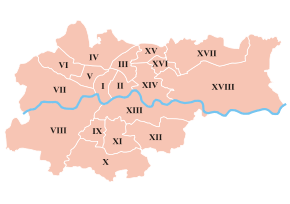

Krakow has been divided into 18 city districts since 1990:

|

|

The administrative districts are not to be confused with the former towns of the same name, because they can include several former towns (districts). For example, Municipal District I includes the originally independent towns of Kazimierz and Kleparz.

Climate and weather

Krakow is located on the threshold from the Atlantic maritime to the continental climate. Depending on the prevailing wind direction, the weather is influenced. Westerly winds (~40 percent) bring humid weather with rain especially in summer, while easterly winds (~22 percent) bring dry and very cold weather especially in winter. The wind blows on average with 11 km/h.

The average temperature in January is about -2 °C, with lows of less than -20 °C not uncommon. The average temperature in July is about +19 °C, but the thermometer can reach +35 °C and more. In general, the weather is very calm with little daily variation.

On very hot summer days, powerful thunderstorms can occur. In recent years, extreme weather phenomena have increased in the region. These include torrential rain with 50 l/m² or even small tornadoes.

| Krakow | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monthly average temperatures and precipitation for Krakow

Source: wetterkontor.de | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Map of the 18 boroughs

History

Prehistory and early Middle Ages

Wawel Hill, where the castle and cathedral stand, was settled as early as 20,000 years ago. People mined and traded salt near Krakow already in prehistoric times.

According to the city's founding myth, first described by Wincenty Kadłubek, "tribal prince Krak built the city on Wawel Hill above a dragon's lair after killing the dragon that lived there". Two burial mounds date from this time, in which, according to tradition, Krak and his daughter Wanda found their final resting place.

In the 9th century the Slavic Wislans are described by Method of Salonika in the area around Krakow. In the 9th century in the vicinity of the later city Chrobates are also mentioned - the relationship between Wislans and Chrobates is disputed by researchers. Both have been described as belonging at times to the Great Moravian Empire hypothetically. Great Moravian chronicles report that Cyril and Methodius advised the (unnamed but powerful) ruler of the Wislanes to be baptized a Christian. It is not known whether the latter accepted the offer. However, it is said that already at this time the first church in Krakow was built on the site of a pagan place of worship (the site of the later Church of St. Andrew). In 965, Krakow was first mentioned in a document by the Arab-Jewish merchant Ibrahim ibn Yaqub - most likely at that time the territory of the Wislanes or White Khrobats belonged to Bohemia. Around 990, most recently in the year of the death of Boleslav II of Bohemia (999), Kraków was conquered by Bolesław I Chrobry, Duke of the Polans, and thus came under the rule of the subsequent Polish Piast dynasty.

By the end of the 10th century Kraków was already an important trading centre and in 1000 Bolesław I the Brave (Bolesław I Chrobry) elevated it to the seat of the Kraków Bishopric. The first stone buildings were erected (a castle on Wawel Hill and various Romanesque sacral buildings).

High Middle Ages

Under Casimir I the Renewer, Krakow became the capital of Poland in 1038. Casimir left Gniezno, which had been destroyed by the Czech ruler Břetislav I and had been the capital of Poland until then, and chose the more conveniently located Cracow as the royal seat. Nevertheless, Gniezno remained the seat of the most important Polish archbishopric and thus the Polish primate. Because of its new role as Polish capital, Krakow developed very rapidly in the 11th century. Numerous buildings in the Romanesque style, including the Wawel Rotunda, the churches of St. Adalbert and St. Andrew, the Tyniec and Norbertanki monasteries, and the Okół district northeast of the Wawel around today's St. Mary Magdalene Square were built. However, this period also saw the conflict of secular with ecclesiastical power in Poland, which culminated in King Bolesław II the Bold, son of Casimir I, slaying Archbishop Stanislaus in St. Michael's Church in 1079. Stanislaus became one of the first patron saints of Poland. Bolesław II had to flee Poland and was later poisoned in Hungary. His brother Władysław I Herman, who succeeded him on the throne in 1079, moved the capital further to Płock for a short time. Władysław Herman and his son Bolesław III Schiefmund are buried in the Płock Cathedral.

But already at the beginning of the 12th century Krakow again secured the position of the Polish capital. After the death of Boleslaw III, Krakow was the capital of the Seniorate of Poland from 1138 to 1320. Under the Seniorate constitution, the princes of Krakow were superior to the other Polish constituent princes and attempted to reunite the Kingdom of Poland. During this period many Jews and Germans immigrated to Kraków and acquired citizenship. In 1228 Petrus scultetus Cracoviensis - the Schulz of Krakow was mentioned, which was the first indication of German law. In the 13th century Krakow was besieged by the Tartars several times. Particularly devastating was the first onslaught of the Mongols (Golden Horde) in 1241 in the course of the Battle of Wahlstatt, which only the Wawel Castle and the Okół district survived. The citizens were able to find shelter in St. Andrew's Church and the castle. After this destruction, Krakow was rebuilt in the Gothic style according to a checkerboard pattern.

In 1257 Krakow was refounded and rebuilt by Boleslaus the Shameful according to Magdeburg city law. During this period, the market squares and the chessboard-like street network of the Old Town were formed, into which older fragments, such as St. Mary's Church or Grodzka Street, were embedded. Bolesław the Timid and his wife, Saint Kinga, promoted underground salt mining in Bochnia and Wieliczka. They thus laid the foundation for the town's wealth in the late Middle Ages. In 1281, the last major Tatar attack on Kraków took place, but the citizens, warned by the tower bell, were able to repel it. According to a modern legend, the Hejnał signal commemorates this, as does the figure of Lajkonik (a warrior with a hobbyhorse).

In 1311, the German burghers, led by the bailiff Albert, rose up against the Polish senior duke Ladislaus I Ellenlang. After putting down the uprising, Ladislaus had most of the Germans banished from the city, and some executed. The nationality of the citizens was checked by a shibboleth: Anyone who could not pronounce soczewica, koło, miele, młyn without mistakes was considered a German. According to the British historian Norman Davies, the first traits of Polish chauvinism appeared during the dispute. Around 1480, 36 percent of the inhabitants with city rights were German-speaking again and German was preached in the most magnificent parish church, St. Mary's Church - until German sermons were moved to St. Barbara's Church by royal decree.

Further repressions against the city were the deprivation of the council election and the founding of neighbouring rival cities such as Kazimierz and Kleparz. The political aspirations of the cities, especially Krakow, were thus permanently broken. In 1320, a Polish king was crowned in Wawel Cathedral for the first time since the partition in 1138, Ladislaus Ellenlang. Krakow remained the coronation and burial place of the Polish kings until 1734, but in the 16th century Warsaw became the capital.

A Latin school of the Krakow Archbishopric existed since 1150 and Casimir III the Great - the son of Władysław Ellenlang - founded the Krakow Academy (later Jagiellonian University) in 1364, the second oldest in Central Europe after the University of Prague. Casimir the Great founded the suburbs of Kazimierz (1335) and Kleparz (1366) and had the Wawel Cathedral and many other churches rebuilt or rebuilt in the Gothic style. In his time, after the plague pogroms of 1348/49, a particularly large number of Jews came to Poland and Krakow, to whom Casimir III secured extensive privileges and, in the extension of the Kalian Edict of Toleration of 1265, religious freedom. Contrary to a widespread misconception, the Jews did not settle in Kazimierz at first, but in today's university quarter around St. Anna Street.

For centuries, the city government of Kraków was under the rule of the Archbishop of Kraków as a prince-bishopric. During the reign of Ladislaus II Jagiello at the end of the 14th century, Krakow became a member of the Hanseatic League, but left it again in 1478.

Late Middle Ages

After the death of Casimir III the Great in 1370, his nephew Louis of Anjou came to power, who was also King of Hungary. After his death, the 12-year-old Hedwig ascended the Polish throne as king (not queen) in 1384. She married the Lithuanian Grand Duke Ladislaus II Jagiello, laying the foundation for the union between the two states. She died very young in 1399 and bequeathed her entire estate to Kraków University. Her husband Władysław II. Jagiełło defeated the Teutonic Order militarily at Tannenberg in 1410 and legally at the Council of Constance in 1416. After the Polish-Lithuanian Union of Krewo in 1385, Kraków developed economically, culturally, scientifically and urbanly as the capital of one of the largest European continental powers. Władysław II. Jagiełło is considered the progenitor of the Jagiellonian dynasty, who ruled Poland-Lithuania, the Kingdom of Bohemia and Hungary, and had strong family ties with Habsburg, Wittelsbach and Vasa. Under their rule Kraków continued to grow and joined the Hanseatic League. The prince-bishop ruled very skillfully from 1434 for the minor sons Władysław II. Jagiełłos, Władysław III of Varna and Casimir IV. Jagiello. Under the latter, Kraków flourished in the late Gothic period. Of the couple's numerous children - his wife Elizabeth of Habsburg was called Mother of the Jagiellons - four alone became kings; seven others held important church offices or married into mostly German noble families. As a result, almost all contemporary European monarchs are related to Casimir IV and Elizabeth. The Italian humanist Kallimachus, who had fled from Rome to Krakow for political-religious reasons, educated the children.

In 1475 the Bavarian Duke George the Rich, heir to the Duchy of Bavaria-Landshut, courted the hand of Hedwig Jagiellonica (Jadwiga Jagiellonka). After a two-month journey, the Landshut princely wedding took place in Landshut.

Many scholars and artists from German-speaking countries, mostly from Franconia, went to Krakow, including book printers. Kasper Straube was the first in 1473, but it was Johann Haller who was able to operate a printing press for a longer period of time in Krakow. In 1488, the humanist Conrad Celtis founded the Sodalitas Litterarum Vistulana, a scholarly society modeled on the Roman Academy. In 1489, Veit Stoß (Polish: Wit Stwosz) from Nuremberg finished work on the high altar of Kraków's St. Mary's Church and then made the marble sarcophagus for Casimir IV. Jagiellonicus, Kallimachus as well as for bishops of Krakow and Poznan. Numerous other artists from Italy, Holland and southern Germany also came to Krakow during the time of Casimir IV and worked in the late Gothic and Renaissance styles. Three of his sons were successively Polish kings, but the eldest was king of Bohemia and Hungary. Kings Alexander and Jan I Olbracht had the city fortifications extended against a feared Turkish onslaught, adding the Barbican in 1499, and laid the foundation stone for the new Jewish quarter in Kazimierz, where the Old Synagogue (the oldest preserved in Central Europe is, of course, Prague's Old Neo-Synagogue from the 13th century) was built in the Renaissance. Her younger brother Sigismund I the Old (Zygmunt I Stary) and his son Sigismund II. August (Zygmunt II August) built Kraków into the center of power of the Jagiellonian lands in Poland-Lithuania and Czechia-Hungary. At that time Krakow had about 30,000 inhabitants. A large number of architectural monuments and artistic treasures of the Gothic and Renaissance periods have been preserved from this cultural heyday of the city. In particular, the castle complex on Wawel Hill and the fortified Old Town - barbican, cloth halls, burghers' houses, etc. - have been preserved. The university also flourished during this period. Nicolaus Copernicus studied here at the end of the 15th century together with numerous German-speaking scholars.

early modern period

Sigismund I the Old had the Gothic royal castle, which had been built by Casimir the Great and burned down in 1499, rebuilt in the Renaissance style by the Florentine masters Francesco Fiorentino and Bartolomeo Berrecci. Berrecci's Sigismund Chapel at Wawel is considered the finest work of Italian Renaissance architecture outside Italy. Berrecci's work was so outstanding that one of his compatriots, who had also come to the Krakow court as an artist, stabbed him to death in Krakow's Market Square in 1534 out of envy. Berrecci was buried with great honors in the Corpus Christi Church in Kazimierz. Sigismund I married Bona Sforza from Milan, who brought many Italian artists to the Krakow court. However, Germans, Dutch and Poles were also artistically active in Krakow under Sigismund I. In 1505, the Balthasar Behem Codex described the statutes of the German-speaking citizens' guilds. In 1520 Johann Beheim arranged for the manufacture of the largest Polish church bell to date (as of 2015), the Sigismund Bell. Peter Vischer from Nuremberg opened a bronze foundry in Kraków. Stanislaus Samostrzelnik created many Renaissance frescoes in Kraków churches. During the same period Hans Dürer, the younger brother of Albrecht Dürer, was court painter to Sigismund I the Old. Hans von Kulmbach painted the altar of St. John in St. Mary's Church.

In 1525, Albrecht, the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, paid homage to the Polish king in Krakow's marketplace and, on the advice of Martin Luther and with the approval of the Polish king, converted the Order's state into a Polish fief. With this Duchy of Prussia as a Polish fief, Albrecht created the first territory to adopt the Lutheran faith. The conflicts over Reformation and Counter-Reformation soon affected Krakow as well. The first Protestant devotions were preached in 1545 and 1547. In the second half of the 16th century there was also a Reformed congregation there, as well as after the split in it, from October 16, 1562 the first congregation of the Polish Brethren. After the royal permission, the Lutheran St. John's Church was opened in 1572. On May 23, 1591 it was destroyed by the Catholic plebs. After that the seat of the parish was moved to Aleksandrowice. The event is considered the turning point in the Polish Counter-Reformation.

Sigismund II. August became King of Poland in 1530 during his father's lifetime and ruled with him until his death in 1548. On the advice of Queen Bona Sforza, he also brought many Italian artists to Krakow, among whom the Santi brothers and Monti Gucci were the most important. The former rebuilt the Cloth Halls in the Renaissance style and created many marble sculptures in the Wawel Cathedral, the latter rebuilt the old synagogue in Kazimierz. In the mid-16th century, work began to replace the German-speaking city government with a Polish or Italian one. In 1572 died the last Jagiellonian king, Sigismund II. August. His successor from France Henry of Valois ruled only one year on the Wawel. He was succeeded by the Hungarian Stephan Báthory, under whom Krakow continued to develop in the Mannerist style. However, in 1596 the Polish and at times Swedish king and temporary tsar of Russia Sigismund III. Wasa (Zygmunt III Waza) moved the residence to Warsaw, which had been the capital of the Duchy of Mazovia until 1526 (the year of the extinction of the Mazovian Piast dynasty), which reverted to the Polish crown. Sigismund preferred Warsaw's proximity to his hereditary Swedish kingdom and to his Russian ambitions. Nevertheless, ambitious Baroque projects were still being built in Kraków, the formal capital, such as the Peter and Paul Church, St. Anne's Church, the Benedictine Church, the Camaldolese Abbey, and so on. However, Krakow's importance declined, accelerated by the plundering during the Swedish invasions of 1655 and 1702 and by the plague, which claimed 20,000 victims. By the end of the 17th century and in the 18th, Kraków lay apart from Polish politics, which now centered in Warsaw. In 1778 the population of Kraków, excluding the suburbs, was 8,894, and in 1782 the total was 9,193. The suburbs (including Kazimierz, Stradom, Kleparz, Garbary) were incorporated into Kraków by the Quadrennial Sejm in 1792.

Austrian period and Republic of Krakow

| Jews in Krakow | |||||||

| Year | Ges.-Bev. | Jews | Share | ||||

| 1857 | 034.200 | 12.937 | 37,8 % | ||||

| 1869 | 049.800 | 17.670 | 35,5 % | ||||

| 1880 | 066.300 | 20.269 | 30,6 % | ||||

| 1890 | 072.400 | 20.939 | 28,0 % | ||||

| 1900 | 091.000 | 25.670 | 28,1 % | ||||

| 1910 | 152.000 | 32.321 | 21,3 % | ||||

| 1921 | 183.706 | 45,229 (nationality: 27,056) | 24,6 (14,7) % | ||||

In 1795, in the course of the Third Partition of Poland, Kraków was assigned to the crown land of Galicia in the Habsburg Monarchy, the Habsburg share from the First Partition of Poland in 1772. From 1809 to 1815 it belonged to the Duchy of Warsaw established by Napoleon Bonaparte, and after the Congress of Vienna it was a condominium as the Republic of Kraków until 1846 under the joint protectorate of its neighbours Russia, Prussia and Austria. The Republic of Kraków became a liberal, prosperous commercial enclave in Central Europe. After the Kraków Uprising of 1846, which failed because of the Galician Peasants' Revolt, Austria annexed Kraków with the consent of Russia and Prussia. The city, now provincial in the Austrian Empire and consequently impoverished, lost its importance. The enterprises dependent on Russia went bankrupt. There followed a period initially characterized by Germanization tendencies of the Viennese leadership, which, however, was replaced by far-reaching autonomy for Galicia after Austria's defeat in the war against the forming Italy and a weakening of the centralists in Vienna by the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867.

In 1847 the Krakow-Upper Silesian Railway reached the city. Shortly after, the construction of numerous fortifications began, the beginning of "Fortress Krakow", which gave new impetus to industrialization (brickworks, quarries). Krakow was connected with Vienna as the capital of that time since 1856 by the k.k. Nordbahn, the most important railway line of the monarchy. From 1855 Krakow was the seat of a district.

In the Cisleithanian part of the real union, now called the imperial and royal monarchy. Monarchy, which was governed liberally and granted equal rights to all nationalities, Krakow once again developed into the centre of Polish art and culture. This period saw the work of Jan Matejko, Stanisław Wyspiański, Jan Kasprowicz, Stanisław Przybyszewski, Juliusz Kossak, Józef Mehoffer and Wojciech Kossak, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz and Leon Chwistek. Kraków became the center of the neo-Romantic Young Poland movement, Art Nouveau, as well as Polish Modernism. Thus, along with Warsaw, Krakow became one of the most important centers of the Polish independence movement. In the last two decades before the First World War, Krakow experienced a rapid modernization, which was not least supported by the Jewish bourgeoisie. In 1900 Kraków ranked sixth in Cisleithania with 91,323 inhabitants, but with only 6.88 km² (5.77 km² excluding Błonia Meadows) it was the most densely populated large city (15,851 inhabitants per square kilometre). Between 1910 and 1915, numerous municipalities were incorporated into Kraków by the Galician Diet, according to the City of Kraków Development Plan of the city's president Juliusz Leo. On 1 April 1910, these were Zakrzówek, Dębniki, Półwsie Zwierzynieckie, Zwierzyniec, Czarna Wieś, Nowa Wieś Narodowa, Krowodrza, Grzegórzki and parts of the municipalities of Prądnik Biały and Prądnik Czerwony with Olsza, totaling 22.74 km² (from 6.88 km² to 29.62 km²). In 1915, this process was completed with the incorporation of Podgórze. "Greater Kraków" then had 46.9 km² and about 180,000 inhabitants.

The Wawel was used by the Imperial and Royal Army as barracks. The Wawel was used as barracks by the imperial and royal army, during which time significant historical elements were removed or damaged. On the occasion of a stay of Emperor Franz Joseph I in Krakow in 1880 (he was a guest in the town house of governor Count Potocki on the Main Market Square), a petition was presented to the monarch to declare the Wawel an imperial residence. Franz Joseph agreed to do so; however, negotiations between the city administration and the Imperial and Royal War Ministry did not lead to the declaration of the Wawel as an imperial residence until 1905. However, it was not until 1905 that the military vacated the royal castle, whereupon restoration work began immediately, which could not be completed until the interwar period.

The Russian border was only a few kilometers away from Krakow. The k.u.k. Army therefore had numerous outer forts built around the walled city in the last third of the 19th century, in order to be able to defend it as a fortress against Russia if necessary. Some of these forts have been preserved.

On April 16, 1918, riots broke out in Krakow (again) because of the poor supply situation, which resulted in anti-Semitic riots. Jewish shops were looted and Jews were beaten with sticks, one man was beaten to death. The funeral procession to the cemetery the following day was also attacked.

See also: History of Galicia

Second Polish Republic

At the end of the First World War, Krakow, like the whole of Galicia, saw itself as part of the re-emerging Polish state from 28 October 1918. This was confirmed in the Treaty of Saint-Germain in September 1919. In 1921 Kraków had 183,706 inhabitants, the majority of whom were of Polish nationality (154,873) and Roman Catholic (136,241). Kraków developed rapidly in the interwar period and was one of the most important cultural centers in Poland, along with Warsaw and Lviv. Krakow became the seat of a voivodeship. Many large buildings were constructed, especially northwest of Kraków's Old Town (Czarna Wieś, Nowa Wieś).

German occupation 1939-1945

At the beginning of World War II, during the invasion of Poland, the German Wehrmacht took Kraków without a fight on 6 September 1939. Western Galicia became part of the General Government for the occupied Polish territories as the Kraków District, with its seat in Kraków. According to Jacek Purchla, Kraków rather than Warsaw became the capital because it was smaller, closer to the border, and would be easier to Germanize. Under Governor General Hans Frank, the infamous Plaszow, Auschwitz and Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camps were built near the city. From 1939 to 1944 Krakow was the seat of the Institute for Spotted Fever and Virus Research of the Army High Command.

The German occupiers more than doubled the size of the city with incorporations in 1941. Hans Frank wanted to build a representative government district around the Błonia Park, but the architect Hubert Ritter, on the other hand, had designed a project "East Nuremberg" in Dębniki, which was more destructive of the cityscape, through expropriations and demolitions. The largest settlement of the several dozen multi-storey buildings, on the other hand, was founded on Reichstrasse, in Nowa Wieś. The occupiers established the Kraków Ghetto in the Podgórze district on the right bank of the Vistula for Jewish citizens of the city, where at times 20,000 people were held as work slaves. In the autumn of 1941, 2,000 people were "selected" from the ghetto for killing, taken away or murdered there. The ghetto area was initially cordoned off with walls. After further deportations (June 1-8 and October 27-28, 1942), the entire compound was divided into Housing District A and Housing District B in December. This was the preparation for the final liquidation, which began on 13 March 1943.

The occupiers destroyed a large part of the art treasures of the Wawel, especially those of Polish artists. However, the building fabric of Krakow was largely preserved, as the Nazi regime considered Krakow to be originally a German city. Krakow was largely spared bombardment and major destruction. However, it lost almost half of its population, almost the entire Jewish community, and especially the university elite in the "Special Action Krakow" of November 1939.

Since 1945

When the Red Army unexpectedly advanced on Krakow in January 1945 in the course of the Vistula-Oder operation, Governor General Frank had all Germans evacuated and left the city while the German troops retreated to the Oder. This allowed the Red Army to enter the virtually undestroyed Kraków on January 19. The blowing up of the city, which was supposedly prevented by this, probably belongs to the realm of legend. The Soviet Union and the Polish communist regime suppressed the bourgeois and aristocratic currents of the Cracovians. On August 11, 1945, there was the Krakow pogrom of Jewish survivors of Nazi terror.

For ideological reasons, the world's largest steelworks at the time and the socialist satellite town of Nowa Huta (New Steelworks) were built in the immediate vicinity of the city (incorporated in 1951). The regime hoped to eliminate the influence of "capitalist intellectuals" by increasing the proportion of "socialist workers". Nowa Huta later became a focal point of social and political reformism against communism during the Solidarność movement. Until the 1990s, emissions from the steelworks damaged Kraków's historic fabric.

In 1978, the Archbishop of Krakow, Karol Wojtyła, was elected Pope and as such took the name John Paul II. He visited Krakow several times during his pontificate. This election had a significant impact on the Polish opposition movement and indirectly on all international politics. In the same year, the Old Town of Krakow and Wawel were declared UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The Wieliczka Salt Mine at the city gates of Kraków also became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1978 and was extended in 2013 to include the Salt Count's Castle and Bochnia. The monasteries in the districts of Tyniec, Bielany and Salwator were on the World Heritage nomination list for several years.

After the Round Table talks in 1988/89 and the first free elections in 1989, Krakow was able to develop freely again. The failures of earlier restoration work were made up for in the 1990s. Motorway connections to Katowice and Wroclaw were built and the airport in Balice was expanded. Now the A4 motorway in the direction of Tarnów is being extended and the "Zakopianka" expressway to the High Tatras is being modernised.

Interned Jews near Krakow, around the end of 1939 (photograph from the Federal Archives)

Parade on 25 October 1940 (photograph from the German Federal Archives)

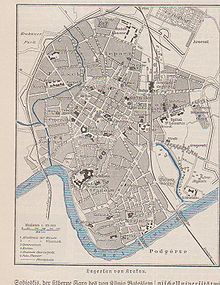

"Greater Krakow" in 1916.

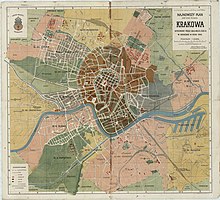

City map from 1896. Almost all streets are named in 2010 as they were then.

Monument to Nicolaus Copernicus in front of the Collegium Novum of the University of Krakow

Leonardo da Vinci's Lady with the Ermine, Czartoryski Museum, Krakow

High altar in the Marienkirche, main work by Veit Stoß

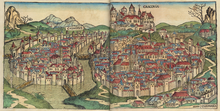

Town view in the Schedel'schen Weltchronik of 1493

View from the Wawel to the old town

View of the Wawel from the Vistula

The surroundings of Krakow before the granting of the town charter

Search within the encyclopedia