Knowledge

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Knowledge (disambiguation).

Knowledge is usually understood as a stock of facts, theories and rules available to individuals or groups, which are characterised by the highest possible degree of certainty, so that their validity or truth is assumed. Certain forms of knowledge or its storage are considered cultural assets.

Paradoxically, descriptions of facts declared as knowledge can be true or false, complete or incomplete. In epistemology knowledge is traditionally determined as true and justified true belief, the problems of this determination are discussed up to the present. Since in direct cognition of the world the present facts come to consciousness filtered and interpreted by the biological perceptual apparatus, it is a challenge to a theory of knowledge whether and how the rendering of reality can be more than a hypothetical model.

In constructivist and falsificationist approaches, individual facts can thus only be regarded as certain knowledge relative to others, with which they represent the world for the cognizers in combination, but the question of ultimate justification can always be raised. Individual modern positions, such as pragmatism or evolutionary epistemology, replace this justification by proof in the social context or by evolutionary fitness: in pragmatism, knowledge is recognized as knowledge by a reference group, which makes it possible to successfully pursue individual and group interests; in evolutionary epistemology, the criteria for knowledge are biologically pre-programmed and subject to mutation and selection.

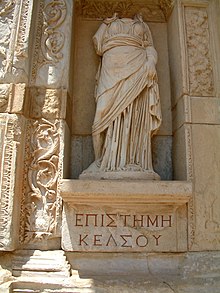

ἐπιστήμη (Episteme), personification of knowledge in the Celsus Library in Ephesus, Turkey.

Etymology

The expression 'knowledge' comes from Old High German wiȥȥan or the Indo-Germanic perfect form *woida 'I have seen', thus also 'I know'. From the Indo-Germanic root *u̯e(i)d (to see) or *weid- are also derived Latin videre 'to see' and Sanskrit veda 'knowledge'.

Philosophical conceptual analysis

The analysis of our concept of knowledge is considered one of the central problems of contemporary epistemology. Already Plato discusses in the Theaetet various attempts to determine the concept of knowledge. However, such an analysis only became a central topic with the emergence of analytic philosophy, according to which the analysis of our language is the core area of philosophy.

Know-how and know-that

A common distinction made by Gilbert Ryle separates so-called knowledge-how (or "practical knowledge") from knowledge-that (or "propositional knowledge"). By knowledge-how Ryle means a skill or disposition, such as the ability to ride a bicycle or play the piano. Linguistically, we express such knowledge in sentences like "Tina knows how to ride a bike" or "Paul knows how to play the piano." Such knowledge usually does not refer to facts and often cannot be easily represented linguistically. For example, a virtuoso piano player cannot convey his knowledge-how to a layman by mere explanation. Ryle himself opposes the "intellectualist" view that knowledge-how can ultimately be reduced to a (possibly complex) set of known propositions. This thesis continues to be discussed in epistemology.

In contrast to knowledge-how, knowledge-that refers directly to propositions, that is, to statements that can be expressed linguistically. For example, we talk about knowledge-that in sentences like "Ilse knows that whales are mammals" or "Frank knows that there is no highest prime number." However, the known proposition need not always be directly embedded in the knowledge ascription. Sentences such as "Lisa knows how many planets there are in the solar system" or "Karl knows what Sarah gets for Christmas" also express knowledge-that is, because there is a proposition known by Lisa or Karl, respectively, to which the sentence alludes. Knowing-that refers to facts, which is why epistemological debates about skepticism, for example, are usually limited to knowing-that.

Definitions of knowledge

According to a thesis held in analytic philosophy, propositional knowledge is a true, justified belief. Accordingly, the proposition "S knows p" is true if (1) p is true (falsehoods S can only believe to be true, but he is then mistaken) (truth condition); (2) S is convinced that p is true (conviction condition); (3) S can give a reason/justification for p being true (justification condition).

The extent to which this analysis was already discussed by Plato is disputed. In the Theaetetus, among other things, the thesis is raised that knowledge is true opinion with understanding, however, this is then rejected.

See also Gettier problem/Historical classification

The idea of definition

First of all, you can only know something if you also have a corresponding opinion: The sentence "I know it is raining, but I do not have an opinion that it is raining." would be a self-contradiction. However, an opinion is not sufficient for knowledge. For instance, one can have false opinions but not false knowledge. So knowledge can only exist if one has a true opinion. But not every true opinion constitutes knowledge. For example, a person may have a true opinion about the next lottery numbers, but he can hardly know what the next lottery numbers will be.

It is now argued by many philosophers that a true opinion must be justified if it is to represent knowledge. For example, one can have knowledge about lottery numbers that have already been drawn, but here justifications are also possible. In the case of future lottery numbers this is not possible, so even a true opinion cannot constitute knowledge here. Such a definition of knowledge also allows a distinction between "knowledge" and "mere opinion" or "belief".

The Gettier problem

→ Main article: Gettier problem

In 1963, the American philosopher Edmund Gettier published an essay in which he claimed to show that even a true, justified opinion does not always constitute knowledge. In Gettier's problem, situations are designed in which true, justified opinions, but no knowledge, exist. Among other things, Gettier discusses the following case: suppose that Smith and Jones applied for a job. Smith has the justifiable opinion that Jones will get the job because the employer has given hints to that effect. In addition, Smith has the justifiable opinion that Jones has ten coins in his pocket. From these two justified opinions follows the equally justified opinion:

(1) The man who will get the job has ten coins in his pocket.

Now, however, Smith - without Smith knowing this - and not Jones gets the job. Moreover, unbeknownst to Smith, he also has ten coins in his pocket. So Smith not only has the justified opinion that (1) is true, the proposition is actually true. Smith thus has the true, justified opinion that (1) is true. Yet, of course, he does not know that (1) is true, because he has no idea how many coins are in his own pocket.

This example seems rather contrived, but it is also only about the basic point that situations can be thought in which a true, justified opinion does not constitute knowledge. This is already enough to show that "knowledge" cannot be defined accordingly.

The "Gettier Debate"

Gettier's essay was followed by an extensive debate. It was generally accepted that Gettier's problem shows that knowledge cannot be defined as true, justified opinion. However, how to deal with the problem raised by Gettier remained controversial. David Armstrong, for instance, argued that all that was needed to arrive at a definition of knowledge was to add a fourth condition. He suggested that true, justified opinions should count as knowledge only if the opinion itself is not derived from false assumptions. Thus, in the example discussed by Gettier, one would not be talking about knowledge because Smith's opinion was based on the false assumption that Jones would get the job. In the 1960s and 1970s, numerous similar proposals were made about a fourth condition for knowledge.

Within this debate, numerous other counterexamples have also been put forward against proposals to define knowledge. A particularly well-known thought experiment comes from Alvin Goldman: Imagine a region in which the inhabitants set up deceptively real fake barns at the side of the road, so that visitors driving through them have the impression of seeing real barn doors, similar to Potemkin villages. Now suppose that a visitor stops by chance in front of the only real barn in the area. This visitor has the opinion that he is in front of a barn. Moreover, this opinion is true and justified by the visual impression. Nevertheless, one would not want to say that he knows he is in front of a real barn. After all, it is only by chance that he has not ended up in front of one of the countless dummies. This example, among others, is a problem for Armstrong's definition, since the visitor does not seem to base his opinion on false assumptions, and thus Armstrong's definition would also attribute knowledge to him.

Goldman himself wanted to support an alternative approach with this example: he argued that the justification condition had to be replaced by a causal reliability condition. What matters, he argued, is not that a person can rationally justify his or her opinion, but rather that the true opinion must be caused in a reliable way. This is not the case in the barn example above: the visitor is only able to reliably recognize barns because he would often be deceived by barn dummies in the present environment. Goldman's theory fits into a series of approaches that call for a reliable method in various ways. These approaches are referred to as reliabilist. A key problem for these approaches is the so-called "generality problem": it is possible for the same person to have a reliable method at a general level, but for it to be unreliable at a more specific level. For example, the visitor in the barn example still has a reliable perception, but his barn perception is very unreliable. On an even more specific level, namely the perception of the very specific barn the visitor is in front of, his perception would again be reliable. If a representative of reliabilism now wants to commit himself to a level of generality, on the one hand there is the problem of defining this level precisely, and on the other hand there is the threat of further counter-examples in which another level represents the more natural perspective.

Is knowledge definable?

The problems presented arise from the claim to give an exact definition, consequently even a single, constructed counter-example is sufficient to refute a definition. In view of this situation, one may ask whether a definition of "knowledge" is necessary or even possible at all. In the spirit of Ludwig Wittgenstein's late philosophy, one can argue, for instance, that "knowledge" is an everyday linguistic concept without sharp boundaries, and that the various uses of "knowledge" are held together only by family resemblances. Such an analysis would rule out a general definition of "knowledge", but would not have to lead to a problematization of the concept of knowledge. One would merely have to give up the idea of being able to define "knowledge" precisely.

Especially influential is Timothy Williamson's thesis that knowledge cannot be explained by means of other concepts, but should rather be regarded as a starting point for other epistemological efforts. This thesis of Williamson's is the core of the currently widespread "knowledge first" epistemology. But even outside this current, the attempt to define knowledge is increasingly being rejected, for example by Ansgar Beckermann, who proposes truth as a better target concept of epistemology.

Semantics and pragmatics of knowledge attributions

In the recent epistemological debate, attempts at a definition have taken a back seat. Instead, there is extensive discussion of how the semantics and pragmatics of sentences of the form "S knows that P" (so-called knowledge ascriptions) interact and what influence context exerts. The following table presents the five main positions in this debate:

| Position | Meaning of knowledge attribution | Main representatives |

| Contextualism | Depends on the context of the utterance of the knowledge attribution | Fred Dretske, Robert Nozick, Stewart Cohen, Keith DeRose, David Kellogg Lewis |

| Subject-sensitive invariantism | Depends on context of the subject (the "knower") | Jeremy Fantl, Matthew MacGrath, Jason Stanley |

| Relativism | Depends on context of consideration | John MacFarlane |

| Infallibilist Pragmatic Invariantism | Requires absolute certainty | Peter K. Unger, Jonathan Schaffer |

| Fallibilist Pragmatic Invariantism | Requires less than absolute certainty | Patrick Rysiew |

From the perspective of contextualism, semantic truth depends directly on certain properties of the context in which the knowledge ascription was made. For example, a court hearing would produce higher standards of knowledge in this respect than a pub conversation. In contrast, subject-sensitive invariantists hold that only the context of the subject about whom the knowledge ascription is made affects the truth of that knowledge ascription. Relativists, on the other hand, hold that the truth of these knowledge ascriptions depends on the context in which they are viewed.

All three of the above positions have in common that they allow for an influence of context on semantics. In contrast, pragmatic invariantists reject such an influence. They argue that it is only because of pragmatic effects that the truth conditions of knowledge ascriptions are subject to variation. A distinction is commonly made between fallibilist and infallibilist manifestations of this position. Infallibilists hold that knowledge presupposes absolute certainty. As a result, many attributions of knowledge turn out to be semantically false, which is why this position is also called skeptical. In contrast, falibilists hold that the truth conditions of knowledge ascriptions are less stringent. This avoids scepticism, but in this way quite different pragmatic effects have to be asserted.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is knowledge?

A: Knowledge is information that is true and can be supported by evidence. It can refer to a theoretical or practical understanding of a subject, and it can be implicit or explicit.

Q: How did Plato define knowledge?

A: Plato defined knowledge as "justified true belief".

Q: What is the most widely accepted way to find reliable knowledge?

A: The most widely accepted way to find reliable knowledge is the scientific method.

Q: Is all scientific knowledge absolute truth?

A: No, all scientific knowledge is provisional, not a claim of absolute truth.

Q: What was the point of Ryle's distinction between "knowing that" and "knowing how"?

A: The point of Ryle's distinction between "knowing that" and "knowing how" was to show that there are different types of understanding when it comes to knowing something - either theoretically or practically.

Q: What kind of claims are certainly true?

A: Claims which are certainly true are circular, based on how we use words or terms. For example, we can correctly claim that there are 360 degrees in a circle since that is part of how circles are defined.

Q: What does Aristotle's syllogism demonstrate?

A: Aristotle's syllogism demonstrates that this kind of reasoning has a machine-like form - if all swans are white, and this is a swan, then it must be white - but in reality not all swans may actually be white.

Search within the encyclopedia