Kingdom of Württemberg

![]()

This article is about the Kingdom of Württemberg (1806-1918). For the history of the territory since the 11th century, see Württemberg.

The Kingdom of Württemberg was a state in the southwest of present-day Germany. It was created on 1 January 1806 as a sovereign kingdom at the instigation of the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, who was striving for political hegemony. The kingdom had emerged from the Duchy of Württemberg (which had been elevated to an electorate in 1803). Its original territory, which was also referred to as Old Württemberg, had been greatly expanded shortly beforehand, mainly in the south and east, as a result of the Imperial Deputation and the Peace of Pressburg, and had thus almost doubled its geographical area.

From 1806 to 1813, Württemberg was a member of the Confederation of the Rhine, which was aligned with the interests of France, and after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, as a result of the decisions of the Congress of Vienna, it was a member of the German Confederation from 1815 to 1866. After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, the kingdom joined the first German nation state proclaimed as a federal state under Prussian leadership.

On the basis of the constitution of 1819, an early constitutional monarchy developed over the years with, compared to many other German states, relatively strong liberal and democratic currents, which were able to assert and strengthen themselves even after the suppression of the German Revolution of 1848/49, which was largely peaceful in Württemberg.

As a result of the German defeat in World War I and the November Revolution of 1918, King Wilhelm II of Württemberg abdicated the throne as one of the last German monarchs. Württemberg was transformed into a parliamentary democracy and remained part of the German Empire as a people's state in the Weimar Republic.

In 1952, its former territory was absorbed into what is now the state of Baden-Württemberg.

Geography

The former Kingdom of Württemberg in its borders as of 1813 lay between 47° 34′ and 49° 35′ north latitude and between 8° 15′ and 10° 30′ east longitude. The greatest extent from north to south was 225 kilometres, the greatest width from west to east 160 kilometres. The boundaries had a total length of 1,800 kilometres. The total area was 19,508 km². In the east, Württemberg bordered on the Kingdom of Bavaria, in the north and west on the Grand Duchy of Baden, and in the south until 1850 on the principalities of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen and Hohenzollern-Hechingen, which from 1850 belonged to Prussia as Hohenzollernsche Lande, and on Lake Constance. Various exclaves, enclaves and other territorial peculiarities existed on the borders to Baden and Hohenzollern. Through the exclave of Wimpfen, Württemberg also had a common border with the Grand Duchy of Hesse.

On a political map of present-day Germany, the former borders of Württemberg with Baden and Hohenzollern can no longer be found, since they were blurred by the enactment of the county reform in Baden-Württemberg on January 1, 1973. Until this reform, the borders were still present in the administrative districts of North Württemberg and South Württemberg-Hohenzollern, and the structure of the districts also coincided with these external borders. In contrast, the territories of the Protestant regional church (not exact, since including the Hohenzollern lands) and the Catholic diocese of Rottenburg-Stuttgart (almost exact, since excluding the Hohenzollern lands) correspond to the old borders of Württemberg to this day.

The hilly and mountainous region comprises in the north the plains of the Triassic formation with valleys rich in vines and fruit, while in the south the plateau country of the Jurassic formation. The climate is Central European temperate in Upper Swabia, in the central Neckar region and in the north, but much harsher in the higher areas of the Swabian Alb, the Allgäu and the Black Forest. The average annual temperature varies between 6 and 10 °C, depending on the area. The abundant forests ensure abundant precipitation. The most important rivers are the Neckar with its tributaries Fils, Rems, Enz, Kocher and Jagst, the Tauber and the Danube with its tributary Iller, which forms the border to Bavaria for 56 kilometres. The area straddles the main European watershed. 70 percent of the area drains to the Rhine, 30 percent to the Danube. Important mineral springs are located in Bad Wildbad and Bad Cannstatt. Larger lakes are Lake Constance and the Federsee in Upper Swabia. The highest point is the Dreifürstenstein on the Hornisgrinde in the Black Forest at 1,151 metres, the highest mountain peak at 1,118 metres is the Schwarze Grat near Isny in the Allgäu. The lowest level, at 125 metres, is near Böttingen, where the Neckar flows from Württemberg into Baden. The average altitude of Württemberg is about 500 meters above sea level.

History

Origin of the kingdom

In the 18th century, the Duchy of Wirtenberg essentially consisted of the former ancestral lands in the middle Neckar region around Stuttgart as well as the associated possessions in the northern Black Forest and in the Swabian Alb. In addition to the area around Heidenheim, the county of Mömpelgard on the left bank of the Rhine was the most important exclave of the duchy. In addition, the county of Horburg and the village of Reichenweier were other smaller exclaves on the left bank of the Rhine in what is now French territory. After the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, which restricted the prerogatives of the nobility and the clergy, coalitions were formed among the European monarchies with the aim of stopping the republican development in France. The first coalition, agreed between Emperor Leopold II and Prussian King Frederick William II in the Pillnitz Declaration, was soon joined by other monarchies. On April 20, 1792, the First Coalition War broke out, won by revolutionary France. In the Peace of Campo Formio on October 17, 1797, Emperor Francis II recognized the Rhine as the eastern border of France. This also affected Mömpelgard and the other possessions of Württemberg on the left bank of the Rhine. The duchy then participated as a partner of Austria in the Second Coalition against France under Napoleon Bonaparte from 1799. In the spring of 1800, the French occupied Württemberg. Since Austria made no effort to defend the country, the Württemberg Duke Frederick II had to join the Austrian retreat with his troops. After this humiliation, his confidence in the alliance with Austria was deeply shaken. In the peace of Lunéville on February 9, 1801, he came to an arrangement with France. His aim was to enlarge the territory on the right bank of the Rhine. The Treaty of Paris of May 20, 1802, secured the existence of the duchy and held out the prospect of compensation for the territories on the left bank of the Rhine. Württemberg had a seat and voting rights in the extraordinary Imperial Deputation, which prepared the Main Imperial Deputation Treaty, which determined the compensation for the lost possessions of German princes on the left bank of the Rhine. Duke Frederick was elevated to the rank of Elector. Numerous small dominions were mediatized and added to the new Electorate under the name of Neuwürttemberg. These included the mediatized imperial cities of Aalen, Giengen an der Brenz, Heilbronn, Rottweil, Esslingen am Neckar, Reutlingen, Schwäbisch Gmünd, Schwäbisch Hall and Weil der Stadt, as well as the following secularized ecclesiastical possessions: the prince-provostry of Ellwangen, the imperial abbey of Zwiefalten, the knightly monastery of Comburg, the monastery of Heiligkreuztal near Riedlingen, the monastery of Schöntal, the monastery of Margrethausen, the monastery of Oberstenfeld, and the Stift-murische part of the village of Dürrenmettstetten. These gains corresponded in total to an area of 1609 square kilometers with 110,000 inhabitants and 700,000 gulden in tax revenue. This contrasted with about 388 square kilometres of territory lost on the left bank of the Rhine with about 14,000 inhabitants and about 250,000 gulden in state revenue. The minister Normann-Ehrenfels was entrusted with setting up the administration of New Württemberg.

On 3 October 1805, Frederick concluded another alliance with Napoleon in Ludwigsburg. Württemberg then participated with troops on the French side in the Third Coalition War. In the Treaties of Brno (10-12 December 1805) and the Peace of Bratislava of 26 December 1805, Vorderösterreich was divided between Württemberg, Bavaria and Baden. This meant that another 125,000 new inhabitants were added to the Electorate of Württemberg. Specifically, these were the following territories: County of Hohenberg, Bailiwick of Swabia, Lordship of Ehingen, the so-called Danube towns of Mengen, Munderkingen, Riedlingen and Saulgau, as well as in the lowlands territories of the Teutonic Order (Amt Hornegg with Neckarsulm and Gundelsheim), territories of the Order of St. John and smaller territories of the Imperial Knighthood. Württemberg became a sovereign kingdom with effect from 1 January 1806. The previous name Wirtenberg was replaced by the more modern spelling Württemberg. The first king was the previous duke and elector Frederick II under the name Frederick (personal name: King Frederick I). With the signing of the Treaty of the Confederation of the Rhine on 12 July 1806, Württemberg left the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. The Confederation of the Rhine added another 270,000 new inhabitants to the Kingdom of Württemberg, who were distributed among the territories of the principalities and counties of Hohenlohe, Königsegg-Aulendorf, Thurn und Taxis, Waldburg and many other lordships in Upper Swabia.

Development of the first years

King Frederick participated with troops in the suppression of the Tyrolean popular uprising in 1809. With the Peace of Schönbrunn on 14 October 1809, the Kingdom of Württemberg was expanded to include the territories of the Teutonic Order near Mergentheim, and a revolt by the population there was bloodily put down. Finally, the Treaty of Paris on 28 February 1810 and related border treaties with Bavaria and Baden increased the population by another 110,000 inhabitants. In addition, Crailsheim and Creglingen as well as the former imperial towns of Bopfingen, Buchhorn, Leutkirch, Ravensburg, Ulm and Wangen and areas of the former county of Montfort were added. In exchange, the old Württemberg dominion of Weiltingen fell to the Kingdom of Bavaria, as well as the Hornberg and St. Georgen offices to the Grand Duchy of Baden. In 1813, the Kingdom of Württemberg also acquired the Hohenzollern dominion of Hirschlatt. In total, Württemberg had thus expanded from the original 9,500 square kilometers with about 650,000 inhabitants to 19,508 square kilometers with about 1,380,000 inhabitants.

In 1812/13, King Frederick took part in Napoleon's war against Russia, from which only a few hundred of the 15,800 Württemberg soldiers returned. Despite this defeat, the kingdom initially continued to stand by France as a member of the Confederation of the Rhine until Napoleon suffered another crushing defeat at the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig in October 1813. Only then did Württemberg switch to the Sixth Coalition, which was led by Austria, Prussia and Russia. On 2 November 1813, King Frederick changed his mind after Austria had guaranteed the state the preservation of its vested rights and the retention of its sovereignty in the Treaty of Fulda.

Württemberg's territorial gains were not revised by the territorial reorganization of Germany at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 and thus indirectly confirmed under international law. Due to its participation in the coalition wars and their consequences, the kingdom experienced an economic decline in its early years, which led to high national debt and the impoverishment of broad sections of the population, even to famine. This economically very difficult situation was further aggravated by the unusually cold year of 1816, which was marked by natural disasters. Thereafter, emigration to Eastern Europe and North America increased by leaps and bounds.

In the first years of the kingdom, Württemberg's involvement in the wars and its loyalty to the alliance with France ensured King Frederick extensive freedom of action in domestic policy. Their goal was the consistent modernization of the administration and the unification of the various territories into a unified and centrally governed overall state. This was all the more difficult because the newly added territories brought a substantial Catholic minority to the previously pure and strictly Protestant Württemberg. Means of modernization were the rigorous abolition of the privileges of respectability in Old Württemberg as well as of the nobility in the newly acquired territories. Resistance to this policy was rigorously combated; a police ministry, a secret police and a censorship authority were set up on the French model. Important reforms of the first years were the separation of the judiciary and the administration, the division of the country into Oberämter and Kreise, the abolition of internal customs duties, and the equal rights of the Catholic and Reformed confessions with the Protestant-Lutheran state confession that had existed since then.

During the negotiations at the Congress of Vienna, the aim was to establish a federal constitution for the newly constituted Germany. The first draft of the concept for a confederation of states was submitted by Metternich to the Assembly of the German Individual States on 23 May 1815. Württemberg, together with Bavaria, opposed this confederation. Because King Frederick wanted to forestall the federal constitution with a constitution of his own, he already submitted a Basic Law of the State to the Diet, which was convened on March 15, 1815. Württemberg did not sign the German Federal Act until September 1, 1815, and thus only belatedly joined the German Confederation, which was founded on June 8, 1815. The draft of the Basic Law of the State met with strong resistance from the Land Estates, which wanted to reinstate the previous constitution based on the Treaty of Tübingen of 1514. The Landstände succeeded in winning the population over to their side in a campaign for the old law. One of the protagonists of this movement was the poet and politician Ludwig Uhland, who wrote the poem Das alte, gute Recht especially for this purpose. The campaign was so effective that the Basic Law of the State presented by King Frederick was not passed. The completely revised constitution was only enacted by his successor King Wilhelm I on 25 September 1819.

Political consolidation after the accession to power of King Wilhelm I.

The relationship between King Frederick and his son William Frederick Charles, later King William I, was marked by strong tensions, both personally and politically. In 1805, Wilhelm openly rebelled against his father, which led to his flight to Paris. Wilhelm tried to persuade France to overthrow Württemberg, but Napoleon refused him. In 1807 Wilhelm and Frederick came to an understanding politically, but their personal and political dislike for each other remained. So it was only logical that the new king began his reign on October 30, 1816, not with his father's name, but with the name Wilhelm, and initiated a comprehensive change of policy. It has been handed down that the population of Württemberg could only with difficulty be kept from celebrating Friedrich's death by soldiers. Together with his wife Queen Katharina, a daughter of the Russian Tsar Paul I, Wilhelm's policies during his first years in power were strongly geared towards alleviating the economic hardship of broad sections of the population. Catherine, who died on January 9, 1819 at the age of only 30, devoted herself with great commitment to social welfare. Thus, the foundation of the Katharinenstift as a girls' school, the Katharinenhospital, the Württembergische Landessparkasse, the University of Hohenheim and other institutions can be traced back to her. On taking office, Wilhelm issued an amnesty and implemented a comprehensive administrative reform based on the new modern constitution of September 25, 1819. However, Frederick's absolutist dictatorship was not replaced by the dualism between the regent and the Land Estates handed down from the Duchy of Württemberg. Instead, the new form of government was based on constitutionalism, which supplemented the monarch's rule with constitutionally defined rights of participation for elected representatives of the people. The constitution thus also became a bracket between the old and the new parts of the country. The old-state opposition practically dissolved. A no less contentious bourgeois opposition of liberal orientation emerged.

Essential components of the reorganization of the administration enforced in connection with the new constitution were local self-government and the separation of the executive and judicial branches. The administration was streamlined and made more transparent. The civil servants, who were beholden to the state and the king, quickly developed into a kind of class and thus a political class that supported the state government.

When Wilhelm I came to power, the national debt amounted to almost 25 million guilders, which was almost four times the annual revenue. These debts were so sustainably reduced in the first 20 years of his reign by the finance ministers Weckherlin, Varnbüler and above all Herdegen that tax cuts were made possible. A particular focus of the king's economic policy was the expansion of agriculture.

In terms of foreign policy, Wilhelm pursued the goal of further streamlining the state structures in Germany and limiting them to the five kingdoms of Prussia, Saxony, Bavaria, Hanover and Württemberg as well as the Empire of Austria. He regarded Prussia and Austria as European powers. The four other German kingdoms were to pursue a common policy aimed at unification into a third German great power through a close alliance. Wilhelm aimed at the mediatization of Baden, Hohenzollern and the acquisition of Alsace. The means to this goal, which was never achieved, was to be the strong family connection with Russia. To this end, in 1776 his aunt Sophie Dorothee was married to the heir to the Russian throne, the later Tsar Paul. To strengthen these ties, Wilhelm's own marriage to their daughter Katharina took place in 1818. After Katharina had already died in 1819, Wilhelm continued to pursue the foreign policy he had developed together with her throughout his reign. So it was only logical that his son and heir to the throne Charles married the Tsar's daughter Olga on 13 July 1846.

Strengthening of the democratic movement and liberalism from 1830 onwards

After the successful French July Revolution of 1830, the liberals gained momentum in almost all of Europe, including Württemberg. In December 1831, they won the elections to the second chamber of the Württemberg state parliament. Wilhelm I then postponed the convening of the Diet for over a year until January 15, 1833. After the dissolution of the Diet on March 22, new elections were held in April, from which the liberals under Friedrich Römer again emerged victorious. Wilhelm then refused to give the elected deputies in the civil service leave of absence to exercise their mandate. Friedrich Römer, Ludwig Uhland and other liberal deputies therefore resigned from the civil service.

In the years 1846 and 1847, famines and increased emigration occurred after crop failures. The until then relatively "content" basic mood of the population changed. Liberal and democratic demands were advocated more forcefully. In January 1848 a protest assembly in Stuttgart demanded an all-German federal parliament, freedom of the press, freedom of association and assembly, the introduction of jury courts and the arming of the people. Wilhelm I first tried to stop the revolution in Württemberg, which had spread to all German states from March 1848 in the wake of the French February Revolution (which had led to the Second French Republic), by making concessions. He reinstated the liberal press law of January 30, 1817, and tolerated a liberal government presided over by Friedrich Römer. The March Ministry, established on March 9, 1848, was the first government in the state with parliamentary legitimacy. This policy avoided major military conflicts in the Kingdom of Württemberg during the March Revolution.

In April 1849, the government and the Landtag decided to accept the imperial constitution adopted at the Paulskirche in Frankfurt, which provided for an all-German nation-state conceived as a small-German solution based on a democratically constituted constitutional monarchy. Wilhelm felt this decision to be a humiliation, but he was the only king among the 29 sovereigns of the German Confederation who approved the constitution adopted by the Frankfurt National Assembly - the kings of Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, Hanover and the Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I rejected it.

After the National Assembly had failed with the rejection of a German imperial crown by the Prussian king, the remaining deputies decided on 30 May 1849 to move the sessions to Stuttgart. From 6 June 1849 onwards, this residual national assembly, sometimes derisively referred to as the rump parliament, met in Stuttgart with an initial 154 deputies under parliamentary president Wilhelm Loewe (1814-1886). When the rump parliament called for tax refusal and, with the support of the imperial constitutional campaign, for an uprising against the governments, it was occupied by Württemberg military on June 18, 1849, and forcibly dissolved after a demonstration march through Stuttgart by the remaining 99 deputies. The non-Württembergian deputies were expelled from the state.

In August 1849, elections to a Constituent Assembly were held in Württemberg, in which the Democrats achieved a majority over the moderate Liberals. While the liberals demanded that the right to vote and stand for election be tied to income level and wealth, the democrats demanded universal, equal and direct suffrage for all men of legal age. At the end of October 1849, the king dismissed the government under Frederick Römer, which had been elected by the state assembly. The ministers were replaced by civil servants under Johannes von Schlayer. When the structure and legal basis of the civil service ministry were rejected by the Landesversammlung, Wilhelm I dissolved it. Two other state assemblies in 1850, in each of which the democrats also had a majority, were also dissolved. Nevertheless, a strong liberal and democratic opposition established itself in Württemberg even after this.

When King Charles took over the government in 1864, he accommodated liberal and democratic demands. Freedom of the press and freedom of association were restored, freedom of trade and freedom of movement were guaranteed. Jews were granted full citizenship rights. Existing marriage restrictions on the poor were lifted. The conservative Chief Minister Joseph von Linden was replaced by the more liberal Karl von Varnbüler (1809-1889).

Württemberg as a federal state in the German Empire

King Karl was, contrary to his father's policy, an advocate of the formation of a German nation state. When, after the war of Prussia and Austria against Denmark in 1864, the tension between the allies Prussia and Austria led to war in 1866, Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden sided with Austria. The Württemberg army was crushed by Prussian troops at Tauberbischofsheim on July 24, 1866, just days before the armistice between Prussia and Austria. Württemberg then concluded an armistice with Prussia on 1 August 1866. The war ended on 23 August with the Peace of Prague, in which Württemberg had to recognise the North German Confederation, which had been founded by Prussia shortly before, and pay war reparations to Prussia.

Prior to this, Württemberg, like Bavaria and Baden, had had to conclude a protection and defence alliance, which initially had to be kept secret, in which territorial integrity was guaranteed, but which transferred the military supreme command to Prussia in the event of war. After the end of the war, the national liberal German Party was founded in Württemberg under the leadership of Julius Hölder, whose goal was the accession of Württemberg to the North German Confederation. It was opposed by the democratic Württemberg People's Party, which had already emerged from the liberal Progress Party in 1864. The People's Party with its leading head Karl Mayer joined with conservatives and representatives of Catholicism to form an alliance whose goal was to prevent a nation state dominated by Prussia.

In the Franco-Prussian War, the Württemberg army was subordinate to the Prussian supreme command in accordance with the alliance concluded. During the war, Württemberg concluded a November Treaty with the North German Confederation on 25 November 1870, which it joined. This accession occurred with the Federal Constitution of January 1, 1871; in the Reich Constitution of April 16, 1871, Württemberg received four of 58 votes in the Bundesrat. Of the 397 members of the Reichstag, 17 came from Württemberg. As reserve rights, the state was granted the administration of the railway, postal and telecommunications systems, the revenues from the beer and spirits tax and its own military administration under Prussian supreme command.

The loss of political power of the state and the ruling house that accompanied entry into the empire was compensated for by a strong focus on Württemberg identity. In 1876, the government was reorganized. The centerpiece of the reform was the establishment of a state ministry under Minister President Hermann von Mittnacht. In the years that followed, King Karl largely withdrew from the operative business of government and, together with Queen Olga, devoted himself more to cultural and social tasks. Although he was head (Summenepiskopus) of the Württemberg Protestant regional church, he placed great emphasis on expanding the rights of the Catholic minority. As a result, the Kingdom of Württemberg was spared a culture war like the one in Prussia.

In his old age, King Charles' homosexuality did not become obvious to broad sections of the population; however, it almost led to a state crisis. The American Charles Woodcock, who had been employed as the king's servant since 1883, came under increasing criticism due to his personal demands, which were considered presumptuous by the government, and due to his behaviour. He was also attacked by the press. The resulting conflict between the King and Prime Minister Mittnacht in 1888 could only be ended through Bismarck's mediation with Woodcock's dismissal.

King Karl died on 6 October 1891 and, as he had no natural children, the regency passed to Wilhelm II, the joint son of his cousin Prince Friedrich von Württemberg and his sister Princess Katharina von Württemberg.

Wilhelm, who had already retired from military service in 1882 at the age of 34, was very distanced from the representational behaviour of Kaiser Wilhelm II and many other regents of the German states. Thus, unlike his predecessors, he did not enter into a marriage alliance with any of the great European dynasties. When his first wife Marie von Waldeck-Pyrmont died in 1882, he did not have her buried in the family vault in Ludwigsburg Palace, but in a civil manner in the cemetery in Ludwigsburg. As king, he did not reside in Stuttgart's New Palace, but lived in the Wilhelmspalais, which corresponded in size and furnishings to a bourgeois villa of the time. He dispensed with the predicate of God's grace on his letterhead, which was customary for monarchs at the time, and wore bourgeois suits instead of uniforms. As a so-called citizen king, he was highly respected by the population. Politically, he aligned himself with the parliamentary majority. His conduct of office was more comparable to that of a president. Although he appointed ministers in accordance with the constitution, he largely left the political work to them and to Parliament. His personal focus was on the promotion of culture. In this way, he made a decisive contribution to the development of Württemberg's cultural independence in the federal empire.

During Wilhelm's reign, Württemberg was thus more democratically organized than the other German states. While Prussia had a three-class electoral system, in Württemberg almost all men over the age of 25 were able to vote for the second chamber of the state parliament. The economic and social structure was more middle-class than large-scale industrial. Accordingly, urbanization and the accompanying impoverishment of the workers were lower than in other parts of the German Reich. Nevertheless, there was notable and increasing housing destitution among the working classes, especially in Stuttgart. Civic social initiatives such as the construction of workers' housing and the founding of consumer associations were not able to eliminate the misery of the workers; however, they contributed to the fact that the living conditions of the lower class were significantly better in comparison to the Ruhr area or Berlin.

The workers' movement, which had also organized itself in Württemberg from the middle of the 19th century, was more moderately oriented than in Prussia. It benefited from the liberal policies of Charles and Wilhelm II of Württemberg. The first workers' association had been founded in Stuttgart in May 1848. The first union-like association was the Gutenberg-Verein der Buchdrucker, also founded in Stuttgart in 1862. The Socialist Law, which was in force in the German Reich from 1878 to 1890, was initially applied with severity, but over the years it was considerably eased in Württemberg, so that well-known Social Democrats such as J.H.W. Dietz, Wilhelm Blos, Georg Bassler and Karl Kautsky were able to operate more or less unhindered in Stuttgart. After the repeal of the Socialist Law in 1890, there was also a wave of founding of Social Democratic associations in Württemberg. Stuttgart became the centre of trade union efforts. The German Metalworkers' Association, founded in 1891, also had its headquarters in Stuttgart. The initial aim of the union's work was to reduce working hours. An initial success was the introduction of the nine-hour day at Bosch in 1894. The increasingly independent cultural identity of the workers' movement became clearly visible with the founding of the Stuttgart Waldheime.

The Landtag election of 1895 resulted in a strong majority for the democratic factions. The supremacy of the German Party was broken. The new majority was formed by the democratic Württemberg People's Party and the Catholic Center, which had been founded before the election. The SPD entered the state parliament for the first time with two seats. In the years that followed, parliamentarism was expanded. A modern party spectrum developed consisting of conservatives, national liberals, the People's Party, the Centre and the SPD. The leading party politicians in the late phase of the Württemberg monarchy were Heinrich von Kraut and Theodor Körner for the conservatives, Friedrich Payer and Conrad Haußmann for the People's Party, Adolf Gröber for the Centre and Wilhelm Keil for the SPD. At the municipal level, Social Democrats participated in politics early on and often found political consensus with bourgeois parties.

In the state parliament, on the other hand, the Social Democratic faction approved the Württemberg state budget only once, in 1907. This was in return for the International Socialist Congress held in Stuttgart in August of that year, the first of its kind on German soil. The Württemberg authorities supported the organizers of the congress, much to the displeasure of the emperor and the imperial government in Berlin. Some 900 delegates, including Stuttgart-based women's rights activist Clara Zetkin and Russian revolutionary Lenin, received a hospitable welcome and were even allowed to use the first-class waiting room of Stuttgart's main railway station. Unhindered, the congress was able to carry out its program in Stuttgart's Liederhalle and hold a major event with public speeches on the Cannstatter Wasen, attended by more than 30,000 people.

The results of the last two Landtag elections for the Second Chamber in the Kingdom of Württemberg are summarized in the following table. After the constitutional reform of 1906, the deputies represented there were elected by the people alone:

| Election Year | Social | People's Party | DeutschePartei | Center |

|

| 1906 | 22.6 %15 | 23.6 %24 | 10.9 %13 | 26.7 %25 | 16.2 %15 |

| 1912 | 26.0 %17 | 19.5 %19 | 12.1 %10 | 26.8 %26 | 15.6 %20 |

Since King Wilhelm II had no sons, it was foreseeable that the succession to the throne would pass from the Protestant line of the House of Württemberg with Albrecht von Württemberg to the Catholic side line. This prospect alarmed the leading Protestant liberal bourgeoisie of Württemberg, and a variety of discussions ensued about the future relationship between church and state. This led to the somewhat paradoxical situation that a Protestant dynasty ruled in the predominantly Catholic neighboring state of Baden, while a Catholic dynasty was to succeed in predominantly Protestant Württemberg.

World War I and the end of the kingdom

On 1 August 1914, the Kingdom of Württemberg, like the other federal states in the Bundesrat, approved the authorization of Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg to declare war on France and Russia. King Wilhelm then signed the call to war to his people on August 2, although he did not share the general enthusiasm of the population for war. By 1918, there were 508,482 Württemberg participants in the war, representing more than one-fifth of the population. 71,641 Württemberg soldiers fell victim to the war.

In the course of the November Revolution, the Württemberg government resigned on November 6, 1918, to make way for a parliamentary government. When State Secretary Philipp Scheidemann proclaimed the republic from a window of the Reichstag in Berlin on November 9, rallies were also held in Stuttgart. Already in the morning demonstrators occupied the Wilhelmspalais. In the afternoon a provisional government was formed in the Landtag from the two socialist parties SPD and USPD under Wilhelm Blos. King Wilhelm then left Stuttgart on the evening of November 9 and moved to the hunting lodge of Bebenhausen. On November 30, he declared his renunciation of the throne and assumed the title of Duke of Württemberg. Württemberg became part of the German Empire as a people's state during the Weimar Republic.

King Wilhelm II monument by Hermann-Christian Wilhelm Zimmerle in front of the Wilhelmspalais in Stuttgart

Standard of King Karl of Württemberg 1864-1891

Karl von Varnbüler was senior minister from 1864 to 1870.

The dissolution of the rump parliament by Württemberg troops - after a book illustration from 1893

Friedrich von Römer on a lithograph 1848

King Wilhelm I. 1822 after a painting by Joseph Karl Stieler

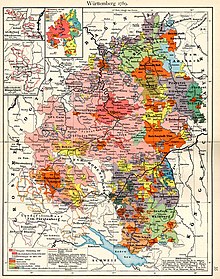

Württemberg 1789

Portrait of King Frederick I of Württemberg in coronation regalia and armour, court painter Johann Baptist Seele (1774-1814), 1806, oil on canvas, 237 cm × 135.5 cm, Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart.

Search within the encyclopedia