Kingdom of Egypt

![]()

This article is about the modern Kingdom of Egypt from 1922 to 1953; for the ancient Egyptian kingdoms, see Ancient Egypt. For the modern state, see Egypt.

The Kingdom of Egypt (Arabic المملكة المصرية, DMG al-Mamlakat al-Miṣrīya), also (New) Egyptian Empire (Arabic الإمبراطورية المصرية الجديدة, DMG al'iimbiraturiat almisriat aljadida) refers to the overall state of the Muhammad Ali dynasty empire in North and East Africa in its final phase during the period from 1922 to 1953.

The Kingdom was granted state independence by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland on 28 February 1922 and came into being with the proclamation of the previous Sultan Fu'ad I as King on 15 March 1922. This had been preceded by a popular uprising against the colonial power in 1919. Thus, after more than 2,000 years of several foreign dominations under a monarchical form of government, a sovereign Egyptian nation state had emerged again for the first time.

The Kingdom of Egypt covered the territory of the present-day republics of Egypt, Sudan and South Sudan and at times included parts of the states of Libya (most of the historical region of Cyrenaika) and Chad (Ennedi and Borkou regions) and the disputed Ilemi Triangle (now controlled by Kenya) and was the largest modern African state to date and the sixth largest state on earth at the time. With over 27 million inhabitants, the monarchy was also the most populous country in the Middle East. As a result, the country had an enormous political and cultural influence in the Arab and Islamic world and thus virtually replaced the Ottoman Empire, which had fallen in 1922 and to which the country had nominally belonged until 1914, as the leading Sunni power. For three decades, the Kingdom of Egypt therefore claimed a regional hegemonic power role politically, militarily and economically vis-à-vis the European colonial powers there and the already independent Arab-Islamic states. In Libya, the empire fought with Italy and local tribal leaders and in Sudan with Great Britain for economic and political supremacy. After the Second World War, it struggled with the Kingdom of Iraq, Iran and Turkey for military and economic dominance in the region. In the newly formed Arab League in 1945, the empire challenged Saudi Arabia for the leading role in the organisation and wrestled with the latter for economic influence in the Kingdom of Yemen. In Palestine, Egypt's expansionist policy led to conflicts of interest with the neighbouring states of Jordan and Syria.

During the time of the kingdom, Egypt's economic and social history was marked by rapid industrialisation and a course of social modernisation that aimed, among other things, at radical secularisation, extensive gender equality and an improvement in the standard of living. Economically and socio-structurally, the empire began to transform itself from an agricultural to Africa's first industrial state from around 1925. Through the expansion of trade in cotton and banking, the service sector also gained in importance. The rapid economic growth was temporarily slowed down by the world economic crisis and the long economic crisis that followed it. Despite considerable political consequences, this did not change the structural development towards an industrial state. This phase of economic and social stabilisation lasted from 1922 to 1939.

Characteristic of the demographic changes in the Monarchy were rapid population growth, internal migration, urbanisation and the intensified immigration of European foreigners. The structure of society was significantly altered by the increase in the urban working-class population and the formation of a new bourgeoisie of technicians, white-collar workers and small and medium-sized civil servants and military personnel. In contrast, the economic importance of crafts and agriculture - in terms of their contributions to the gross national product - tended to decline. Nevertheless, the Egyptian and Sudanese aristocracy were able to maintain their high social prestige, their dominant role in the military, diplomacy and higher civil administration. Moreover, public opinion gained weight through the rise of several mass associations and parties and the development of radio and newspapers into mass media.

Domestic and foreign policy development was determined by the nationalist Wafd Party, especially in the early years. Its various governments pursued a relatively liberal course with many political and social reforms. In foreign policy, attempts were made to secure the empire through a complex system of alliances with the great powers Italy, France and Great Britain (e.g. Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936).

The period after the death of King Fu'ad I in 1936 led to considerable personal influence of his son Faruq on day-to-day politics. His reign was also marked by corruption and a contradictory foreign policy that vacillated between aligning itself with the fascist dictatorships in Europe and the Western democratic states, ultimately leading Egypt into isolation on the eve of the Second World War. The economic situation also increasingly deteriorated with the Great Depression from 1930 onwards. The subsequent rise of the fascist Young Egyptian Party and the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood led to a five-year dictatorship (1930-1935).

In 1940, Egypt was occupied by Great Britain. The country was involved in a multi-front war and it was not until 1942 that the troops of the British Empire were able to repel the Axis invasion that had been ongoing since 1940. The deep economic and political crisis resulting from the war in 1946 and the continued considerable British influence led to a strong loss of support for the monarchy among the population and the military.

The decline and end of the empire came in the wake of the Cold War. In this, the kingdom initially gained enormous geopolitical influence as a strategically important power. As an initially pro-Western non-aligned state, the country intervened symbolically successfully in the Greek Civil War against the communist insurgents there. With the defeat of Egyptian-Arab troops by the newly created state of Israel in the Palestine War of 1948/49, Egypt lost its position of power in the region and broke politically with the West in 1951. The increasing repression of the left-liberal, communist and Islamist opposition in the post-war period led to multifaceted social tensions that culminated in the "Revolution of 23 July" in 1952, in which Faruq was overthrown. The subsequent dictatorship of the military during the reign of the minor Fu'ad II until 1953 led to increased alignment with the Soviet Union and its satellite states and the strengthening of Arab nationalism. On 18 June 1953, the centuries-old monarchy was abolished and the territory of the empire was divided up. The northern part of the country became the Republic of Egypt in the same year, the southern part the Republic of Sudan in 1956. The two subsequent states abolished the aristocracy, expelled the Muhammad Ali dynasty from the country and Egypt carried out a land reform. Not least because of the experiences of the following decades (the Six-Day War in 1967, the rise of Islamism, the dictatorship of Husni Mubarak from 1983 to 2011, military rule and the war of secession in Sudan from 1969 to 1985 and from 1983 to 2005), there is a positive culture of remembrance of the Kingdom of Egypt in the successor states.

Prehistory

Ottoman rule and establishment of the Muhammad Ali dynasty

→ Main article: Ottoman rule in Egypt

The roots of the Kingdom of Egypt lay in the conquest of the country by the Ottoman Sultan Selim I. Afterwards, Egypt became a major province of the Ottoman Empire as Eyâlet. In the 16th century, the country became an important base for the Ottomans to expand in North Africa and Arabia. The constant military presence of the Ottomans resulted in profound cuts in Egyptian civil society and previous economic institutions. It led to a weakening of the economic system. Eyâlet Egypt subsequently became impoverished and suffered six famines between 1687 and 1731. The famine of 1784 alone cost it about one sixth of the population of the time their lives.

In 1798, in the course of the Second Coalition War between the European monarchies and the revolutionary French Republic, the conquest of Egypt by Napoleon Bonaparte began. The Egyptian expedition only ended with the expulsion of the French in 1801 by the Ottomans. Thereafter, internal power struggles broke out in the country, with the Mamluks, parts of the British forces, the Ottomans and Albanians, nominally loyal to the Ottomans, vying for power. The commander of the Albanian regiments, Muhammad Ali Pasha, emerged victorious from this chaos. Muhammad Ali was granted the title of Wālī (Governor) of Egypt by Sultan Selim III in 1805. In the same year, he founded the dynasty of the same name.

After coming to power, Muhammad Ali Pasha shifted his focus to the military. He created the modern Egyptian army and in several campaigns conquered Sudan (1820-1824), Syria (1833), parts of the Arabian Peninsula, Anatolia and Greece (see Greek Revolution). In 1841, the leading European powers, fearing that Muhammad Ali might overthrow the Ottoman Empire, put the brakes on Egypt's territorial expansion and forced the province to return most of its conquests to the Ottomans. However, Muhammad Ali was granted the Turkish-Egyptian Sudan and allowed to continue to rule largely independently. He then modernised the country. To do this, he sent Egyptian and Sudanese students to the West to make the new techniques of the great powers accessible to Egypt and invited foreign training missions to Egypt. He tried to industrialise the country, had a system of canals built for irrigation and transport, and reformed the civil service.

In 1820, Egypt began exporting cotton. The cultivation was supported and promoted by Muhammad Ali. This resulted in a monoculture that would shape Egypt until the end of the century. The social impact of this project was enormous: land ownership was restricted, many foreigners entered the country and production was shifted to international markets.

In September 1848, Muhammad Ali, who was to die in 1849, handed over the office of Wālī to his son Ibrahim, then he was succeeded by his grandson Abbas I (in November 1848), then Said (in 1854) and Ismail (in 1863). Abbas ruled Egypt in a relatively restrained manner, while Said and Ismail were ambitious developers. The Suez Canal, built in partnership with France from 1859 to 1869, was completed in November. However, the construction came at a high cost.

British rule until the First World War

→ Main article: British rule in Egypt

The construction of the Suez Canal, with its high costs, had two effects: it led to enormous national debts of Egypt to the European banks and caused discontent among the local population because of the burdensome taxation. In 1875, Ismail was forced to sell shares of the canal to the British government. Within three years, this led to the introduction of British and French financial control and made the country dependent on the three great powers of France, Britain and the Kingdom of Italy. France and Britain also reserved the right to each send an official to assist the Egyptian government.

The influence of European countries on Egypt gave rise to an Islamic and Arab nationalist opposition. However, the most dangerous opposition for the British at this time was the Egyptian army, which was largely dominated by Albanians and the Mamluks. The military saw a threat to its previous privileges above all in the reorientation of economic development.

A large military demonstration by the Urabi movement in September 1881 forced the Khedive Tawfiq to dismiss his Prime Minister Riyad Pasha and issue several emergency decrees. Europeans already living in the country retreated to their neighbourhoods, like Alexandria, and organised self-defence against nationalist attacks.

The unrest led to the dispatch of French and British warships to the Egyptian coast in April 1882. However, the invasion did not begin until August, after the Urabi movement had taken power in Egypt in June. It began nationalising all assets in Egypt and encouraged anti-European violence and protests. In conjunction with an Islamic revolution in British India, the British sent an Anglo-Indian expeditionary force to capture the Suez Canal. At the same time, French forces landed in Alexandria. The operation succeeded and the Egyptian army was defeated at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir in September 1882. Tawfiq then took control of the country again.

The aim of the invasion had been to restore political stability in Egypt under a government of khedives and to make the country accessible to foreign influences again. However, the permanent occupation of Egypt soon became apparent. In 1883, a British Consulate General for Egypt was created, with Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer becoming its first consul. Cromer believed that Egypt's political stability would require financial stability and created a programme of long-term investment in Egypt's productive resources, especially in cotton production, the mainstay of the country's export earnings.

In 1881, a religious uprising broke out in Sudan, which still belonged to Egypt. The rebel leader Muhammad Ahmad proclaimed himself the Mahdi of the country and conquered large parts of the state by 1885. With the capture of the city of Khartoum in 1884/1885 and the proclamation of the Caliphate of Omdurman, Egypt had finally lost control over Sudan.

In 1896, during the reign of Tewfik's son Abbas II. a massive Anglo-Egyptian force under the command of General Herbert Kitchener began the reconquest of Sudan. In the Battle of Umm Diwaykarat in 1899, Egyptian rule in Sudan was restored.

In 1906, the Dinshavai incident led to nationwide protests in Egypt and the formation of new nationalist political camps, some of which were funded and supported by the German Empire. Britain's main goal, in the early 20th century, in Egypt was to eliminate these groups once again. By the eve of the First World War, Egypt under British rule had developed into a regional economic power and a major Middle Eastern trading destination. Immigrants from less stable parts of the world, including Greeks, Jews and Armenians, as well as many British, French and Italians, began to go to Egypt and settle there. The number of foreigners in the country increased from 10,000 in the 1830s to 90,000 in the 1840s and to over 1.5 million in the 1880s.

Egypt under the Muhammad Ali dynasty from its foundation to 1914

Map of the Khedivate of Egypt from 1912

Muhammad Ali Pasha, painting by Auguste Couder 1840

The road to independence

Emergence of the Sultanate of Egypt

→ Main article: Sultanate of Egypt

In December 1914, following the declaration of war by the Ottoman Empire, of which Egypt was still nominally a part, Britain declared a protectorate over Egypt and deposed the previous Khedive Abbas II, replacing him with Hussein Kamil, who proclaimed himself the first Egyptian Sultan.

At the beginning of the First World War, the main target of the Ottoman army in the Middle East was the Suez Canal area, which was strategically very important for Great Britain and the shortest connection to its colonies. In January 1915, it crossed the Sinai Peninsula and advanced towards the Canal. In the first half of 1916, the Egyptians and British managed to recapture parts of the Sinai Peninsula and repulse the Ottomans. After the battle of Rafah in January 1917, the Turkish troops were completely driven out of the Sinai.

When the war ended, nationalists again began to demand Egyptian independence from Britain. They were influenced and supported by US President Woodrow Wilson, who defended self-determination for all nations. In September 1918, Egypt took its first steps towards independence by forming its own delegation (from Arabic وفد Wafd) for the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. The idea for such a delegation came from the Umma Party (حزب الأمة, Hizb al-Umma), whose prominent members such as Lutfi as Sayyid, Saad Zaghlul, Mohamed Mahmoud Khalil, Ali Sharawi and Abd al Aziz Fahmi were to be the delegates.

On 13 November 1918, as Egypt celebrated Yawm al Jihad (Day of Struggle), Zaghlul, Fahmi and Sharawi were granted an audience with the British High Commissioner to Egypt Reginald Wingate. They demanded complete independence with the stipulations that Britain be allowed to control the Suez Canal and oversee the country's public debt. They also asked for permission to go to London to bring their demands before the British government under David Lloyd George. On the same day, the Egyptians formed a delegation for this purpose. However, the British refused to allow the delegation to go to London.

On 8 March 1919, Zaghlul and three other members of the Wafd were arrested and deported to Malta the next day. An action that triggered the 1919 revolution.

First World War and its consequences

The 1919 revolution, called the "first revolution" in Egypt, marked the end of British rule in Egypt. Representatives of all social classes (nobles, upper classes, clergy, workers and peasants) took part in the popular uprising. There were violent clashes in Cairo and the provincial towns of Lower Egypt, especially Tanta, and the uprising spread to Cyrenaica, north-eastern Chad, Sudan and Upper Egypt.

The deportation of the Wafd delegates also sparked student demonstrations and escalated with calls for strikes by students, government officials, professionals, women and transport workers. Within a week, Egypt's infrastructure had been shut down by general strikes and unrest. Railway lines and telegraph lines were disrupted, taxi drivers refused to work, lawyers did not show up for court proceedings and so on.The revolution was largely carried by women from the upper strata of society. They organised strikes, demonstrations and boycotts of British goods and wrote petitions which they sent to foreign embassies.

The British reacted to the unrest with harsh repressive measures that led to the deaths of more than 800 Egyptians and 31 Europeans by the summer of 1919.

In November 1919, a commission headed by Alfred Milner was sent to Egypt to try to clarify the tense situation. However, cooperation with the commission was boycotted by the nationalists, who rejected a continuation of the protectorate as demanded by Britain. The arrival of Milner and his advisers was accompanied by renewed strikes by students, lawyers, professionals and workers.

In 1920, Milner submitted his report to British Foreign Secretary George Curzon and recommended that he abolish the protectorate and establish a British-Egyptian military alliance. Curzon agreed and invited an Egyptian delegation led by Saad Zaghlul and Adli Yakan Pasha to London. The delegation arrived in London in June 1920 and by August 1920 negotiated a treaty that would bring Egypt into broad independence from Britain. In February 1921, the British Parliament approved the agreement and Egypt was invited to send another delegation to London to reach a final agreement. The second delegation arrived in June 1921 and obtained far-reaching concessions from the British. Egypt was guaranteed full sovereignty over itself and the Sudan, but the British retained control over the Suez Canal. However, parts of the agreement were not fulfilled later.

Shortly before Egypt's planned declaration of independence, there was renewed unrest in Cairo in November and December, which the British were unable to bring under their control. In December 1921, the British authorities in Cairo imposed martial law and had Zaghlul exiled to the Seychelles.

.jpg)

Revolutionaries with the religious symbols of the Islamic crescent, the Christian cross and the Jewish Star of David during the 1919 Revolution, Cairo.

Egyptian Revolutionary Flag

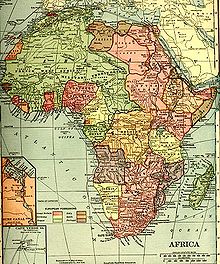

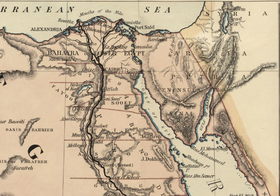

Africa and the Sultanate of Egypt 1917

Granting of independence and foundation of the empire

→ Main article: Declaration of Independence of Egypt

On 28 February 1922, Egypt was granted broad state independence by Great Britain, which continued to regard itself as Egypt's protecting power, in the Declaration to Egypt. The treaty was ratified by the Egyptian and the liberal British government of David Lloyd George.

This was done under four restrictions. British troops remained stationed in the country for external defence. In addition, the British retained far-reaching rights of intervention in Egypt and in the jointly administered Sudan, which limited the country's foreign policy independence. Furthermore, these included rights regarding transport routes, such as the Suez Canal and the Nile, and to secure the claims of foreign creditors. On the subject of Egyptian foreign policy, a reduction of British interventions as well as a reduction of British troops, personnel and military bases in the kingdom were stipulated. In return, Egypt undertook to support the British Empire in times of crisis, to provide the use of airspace, and to allow the British to operate military bases on Egyptian territory. Other political, economic and cultural commissions were also included.

The treaty met with rejection from parts of both sides. Some Egyptian nationalists saw the country's independence as not complete. Nevertheless, the British succeeded in splitting the Egyptian national movement and calming the country. In London, in addition to the failure in Syria to support Arab nationalists against the French, the treaty led to the fall of Lloyd George in October 1922 in the wake of the Chanak crisis and the formation of a Conservative government under Andrew Bonar Law that recognised Egyptian independence.

Shortly after independence was granted, the previous Sultan, the son of the Khedive Ismail Pasha, Fu'ad I, who was highly respected and popular among the population, proclaimed himself King of Egypt in Cairo on 15 March 1922. The monarchy's first prime minister was Abdel Khalek Sarwat Pasha, who had been head of government since 16 March 1922. Egypt was thus the only sovereign state in Africa, along with Liberia (independent since 1847), the Abyssinian Empire (never colonised) and the South African Union (independent since 1910).

Fu'ad I took his title of "king" from the tradition of the pharaohs (Hebrew for "king") in ancient Egypt. The country was therefore also called the "New Egyptian Empire" (الإمبراطورية المصرية الجديدة al-imbiraturia al-misriyya al-jadida). On 4 November 1922, it once again gained international attention with the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun.

The first parliamentary elections were held in January 1924. The newly formed Wafd Party emerged victorious with 87.4 %. Prior to this, a 30-member committee of representatives from all walks of life had worked out a new constitution together with the king, which came into force on 19 April 1923 and made the Kingdom of Egypt a federal and constitutional hereditary monarchy under a parliamentary system of government, oriented towards the monarchical principle. The new constitution was mainly modelled on the constitution of the Kingdom of Belgium of 1831 and partly on the constitutions of Prussia, Japan, Italy, the United Kingdom, the United States, and so on. It nevertheless guaranteed the ruling monarch far-reaching powers. Fu'ad I had the right of veto and frequently made use of his right to dissolve parliament. During his reign, no parliament could constitutionally end its legislative term.

A flag with three white stars representing Muslims, Christians and Jews, enclosed by a crescent moon, was chosen as the new state symbols. The coat of arms of the Muhammad Ali dynasty served as the state emblem.

King Fu'ad I in the new Egyptian Parliament, 1924

Founder and stabilisation phase

New frontiers, secularisation, social reforms

See also: State Crisis in Egypt 1928 and Sudan Crisis

On 26 January 1924, Saad Zaghlul was elected by the Egyptian parliament as the new prime minister. He succeeded Abdel Fattah Yahya Ibrahim Pasha (in office since 15 March 1923). He pursued a course of modernisation and was in conflict with Great Britain. Zaghlul demanded that the British recognise Egyptian sovereignty in Sudan ("Unity of the Nile Valley") and wanted to completely remove the Egyptian army from British influence.

On 19 November 1924, an assassination attempt was made in Cairo on the British Governor General of Sudan and British Commander-in-Chief of Egyptian Forces (Sirdar) Lee Stack, who died as a result on 20 November and pro-Egyptian riots broke out in Sudan.

The murder led to a state crisis in Egypt and became the first stress test for the young state. When the British demanded a public apology from the Egyptian government for the act, the payment of a heavy fine, the expansion of irrigation systems in Gezira for the benefit of European settlers and the withdrawal of all Egyptian officers and Egyptian army units from Sudan, supposedly to protect foreign investors, the crisis escalated. It is true that the Zaghlul met the first demand. The second failed due to the resistance of King Fu'ad I.

The Egyptian troops did not see themselves bound by their oath to the Egyptian king to obey the orders of their British officers and mutinied. The British tried to put down the mutiny by force, removing parts of the Egyptian army from Sudan and liquidating some important Egyptian officials from the administration. Nevertheless, it was only after pressure from the Egyptian government that the rebellion was calmed down and the condominium remained legally in place de jure, but in practice Egypt had lost much of its influence over the administration of Sudan. However, the uprising, along with the Mahdi uprising, was one of the most successful uprisings in the Third World against colonialism.

In the period following the attempted overthrow, the British administration regarded most Sudanese, some of whom had supported the revolt, as potential spreaders of "dangerous" nationalist ideas from Egypt. Lee Stack's successor, Geoffrey Francis Archer, was appointed Governor General of Sudan in 1925 and began forming his own Sudan Defence Force, completely separate from the Egyptian army. The new army was under his command and included only pro-British Sudanese officers who had previously served in the Egyptian army.

On 24 November, Zaghlul was deposed by Fu'ad I, who was increasingly in conflict with the Wafd party, and under pressure from the British, and replaced by Ahmed Ziwar Pasha. Ahmed Ziwar Pasha continued the modernisation course and he and his successors established the final borders of the Kingdom of Egypt with its neighbouring states of Italian Eritrea and Abyssinia to the east, British Uganda and Kenya to the south, Belgian Congo, French Equatorial Africa and Italian Libya to the west.

In 1926, Egypt ceded the Kufra oases and parts of today's Libyan provinces of al-Kufra, Murzuq and al-Wahat to Italian Libya, despite widespread resistance up to the royal family and unrest among the population. However, the territories were not conquered by Italian troops until 1931. After a treaty for the final Egyptian-Libyan border settlement, the small town of al-Jaghbub with al-Butnan was still ceded in 1926 at the suggestion of Great Britain. In the same year, in an Egyptian-French border agreement, Egypt ceded a 152.436 km² territory, which included the north of today's Chadian regions of Ennedi and Borkou, to the colony of French Equatorial Africa.

In 1934, the Sarra Triangle, which included the oasis of Ma'tan as-Sarra, was separated from Anglo-Egyptian Sudan and annexed to Libya. In total, the Egyptian monarchy ceded an area the size of 855,370 km² to Libya with Sudan by 1934. Nevertheless, the land mass of the kingdom remained enormous at over 3.5 million square kilometres. The kingdom was by far the largest state in Africa, followed by the Belgian Congo with over 2.3 million km², the largest Arab and Muslim country, and by 1930 the fourth largest contiguous independent state in the world after the Soviet Union, the Republic of China, the United States and Brazil.

From 1925 onwards, the ruling Wafd party aimed at secularisation and, despite the preservation of the aristocracy, a modernisation of the previous social order. Although Islam formally remained the state religion in the constitution of 1923, the principle of separation between religion and state de facto prevailed and the kingdom can be considered a secular state. The Wafd Party went even further. It initiated a fundamental upheaval of the previous religious structures. Among other things, the public wearing of the burqa was banned (but mostly tolerated) and a reorganisation of marital divorce law was carried out, although women were still denied the right to vote until 1956. For the Wafd Party, the process of gender equality that had been ongoing since the 1919 revolution was largely complete. Other reforms included the abolition of the Islamic calendar and the introduction of the European Gregorian calendar, which was mainly due to Adli Yakan Pasha and Mustafa an-Nahhas Pasha. In the Egyptian school system, too, the various secular and sometimes anti-religious governments of the Wafd went toe-to-toe with Islam. All religious influences were banned from schools until Fu'ad I's death in 1936, and religious and Koranic instruction was abolished. From 1930 onwards, the Wafd governments increasingly expelled numerous clerics from the country, as the party considered them a danger to the nation and the royalty, and in 1923 replaced the Qur'an-oriented jurisprudence of the Sharia with a civil code. The legal norms were modelled on the civil code. The entire economic, criminal and civil law, which still stemmed from Ottoman times, was also redesigned according to Western models. The modern law of succession and family law of the civil code and Italian criminal law were also adopted. The Egyptian government took its cue from Turkey under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and from Iran, which appeared to be rising rapidly under the rule of Shah Reza Shah Pahlavi.

In opposition to the social reforms was the Muslim Brotherhood. It was founded in 1928 by Hasan al-Bannā and campaigned for the end of British domination in Egypt and actively for the strengthening of Islam and the Ummah. It also called for the abolition of the aristocracy and the end of the monarchy, which put it in conflict with the secular Egyptian state. Its popularity therefore remained limited in the first years after its founding. Even staged boycotts of Jewish and Coptic shops were unsuccessful.

Economic upswing, failure of the liberal state from 1930, instability

In 1929, the Wafd won another clear election victory and the party's leader Mustafa an-Nahhas Pasha was appointed prime minister for the second time on 1 January 1930.

During his tenure, conflicts arose with King Fu'ad I, as Nahhas Pasha considered himself a defender of the constitutional order and had already been deposed by the monarch in 1928 when he spoke out against the king's suspension of the constitution. He also began to modernise the country, which had already been promised by the Wafd Party in 1924. He was responsible for the reorganisation of the Cairo Stock Exchange, which thereafter became one of the five largest stock exchanges in the world, and carried out tax and agricultural reform. Nahhas Pasha's main concern, however, was to increase the industrialisation of the country in order to be on a par with European nations. New industrial plants were built in Cairo, Alexandria and Giza. Most of the port cities, such as Port Said or Suez, were greatly expanded and new roads and railway lines, some of which reached as far as present-day southern Sudan, were built. New electricity grids and a renewed communication system were also formed to supply the whole kingdom with electricity and information respectively. Egypt was thus the first industrialised state in Africa and the most modern country in the Middle East.

Despite strong popular support, the Wafd Party suffered two decisive defeats on the domestic and foreign policy fronts between 1930 and 1935. The first was the failure to reconcile with Britain, which was prepared to make serious concessions. Talks to this end were initially successful, but were broken off due to disagreements over the disputed status of Sudan. At the same time, the emerging world economic crisis pushed the king to take the political initiative. Fu'ad I dissolved parliament and appointed Ismail Sedki Pasha as the new prime minister on 20 June 1930. Ismail Sedki was party leader of the Hizb ash-Shaab ("People's Party"), a monarchist party that advocated more political rights for the king. Fu'ad I let the party have its way and Sedki began to undermine the previous democratic institutions in favour of royalty. His first official act was to resign from the party he had founded, which refused to support his course. The parliament also refused to support him. When, in the summer of 1933, Sedki presented an unconstitutional decree to the then Speaker of Parliament, Wisa Wasif, and he refused to sign it, riots broke out in the towns and villages. In addition, there were calls for violence from the Muslim Brotherhood, which incited against Jews and Coptic Christians.

Sedki crushed the revolt with police violence. In parliament, he was able to get the majority of MPs behind him through bribery. He sentenced the leading protesters to heavy fines and exiled some of them to Sudan. On 27 October 1930, he announced that he would draft a new constitution that would significantly expand the powers of the king and the government. However, he met with fierce criticism in the press and the opposition parties refused to cooperate with him in any way. They boycotted the 1931 parliamentary elections and violence erupted again. Sedki then arbitrarily appointed people he had selected as new members of parliament.

From 1932 onwards, Sedki became increasingly radicalised politically and began to establish a dictatorship. The work of opposition political parties and associations was restricted under his rule, press censorship was introduced and numerous alleged and actual opponents were arrested or murdered. From 1933 onwards, Sedki was empowered to issue decrees with the force of law and was formally accountable only to the monarch. During this time, he also had a personality cult conducted around him.

The creeping seizure of power met with resistance from Fu'ad I, who had effectively been played up against the wall by Sedki and no longer carried any weight in Egyptian political life. Parts of the government, led by the Minister of Justice Ali Maher Pasha, also turned against the dictatorship. In September 1933, Sedki was dismissed by the king and the dictatorship was replaced by an authoritarian monarchy.

Economic crisis, return to democracy, reconciliation with Great Britain

→ Main article: Anglo-Egyptian Treaty

After the New York stock market crash in October 1929, the world economic crisis also hit Egypt from 1930 onwards. Foreign trade fell considerably and the country could hardly export cotton. Industrial production also fell by more than 60 %. There was a short-lived hyperinflation and unemployment rose to a quarter of the population by 1935. The situation was particularly disastrous for the peasants. Producer prices for agricultural products fell by 50 % from 1929 to 1933, causing production to decline and impoverishing many people.

The severe economic crisis in Egypt was to be solved by Abdel Fattah Yahya Ibrahim Pasha. On 22 September 1934, Fu'ad I appointed him as the new prime minister. During his term in office, he tried to cope by creating jobs, regulating the financial markets and introducing social insurance. However, the wages of the Egyptian workforce remained low. Workers' unrest ensued and the Egyptian Communist Party, founded in 1921, emerged for the first time as a significant political force. In November 1934, Fu'ad I deposed Abdel Fattah Yahya Ibrahim Pasha. The new prime minister on 15 November was Muhammad Tawfiq Nasim Pasha, who, however, continued the measures of his predecessor instead of taking a new course.

The National Socialist seizure of power in the German Reich in 1933 also led to a burgeoning of fascism in Egypt. The Egyptian branch of the National Socialist foreign organisation NSDAP/AO had already existed in Egypt since 1926. Since the group was not very successful at first, Hitler successfully threatened to boycott Egyptian cotton after the transfer of power. The Egyptian government then made a U-turn on its previously anti-Nazi policy and condemned the anti-German boycott movement in the country. In the face of the German threat, the Egyptian press now also pilloried the Jews as destroyers of the Egyptian economy, although such campaigns stopped again as early as 1936. In 1935, the Nazis opened a branch of the German Intelligence Bureau in Cairo as a propaganda and intelligence centre. Just three years later, the German Reich had risen to become the second largest importer of Egyptian goods.

In October 1933, Ahmed Husayn founded the ultra-nationalist Young Egyptian Party, which advocated the founding of a new Egyptian empire and laid claim to Egypt's 1922 borders. The party had a paramilitary organisation in the form of the so-called Green Shirts and was mainly oriented towards National Socialism with its radical anti-Semitism. The party and the Muslim Brotherhood subsequently became more and more popular and gained political weight. As a result, the Wafd Party and the Egyptian parliament urged Fu'ad I to abrogate the 1930 constitution in 1935, supposedly to prevent another dictatorship. After initial hesitation, the king agreed.

On 30 January 1936, Ali Maher Pasha of Fu'ad I's Wafd Party was appointed Prime Minister. On 28 April 1936, after 14 years of rule and at the age of 68, the king died. He was succeeded by his sixteen-year-old son Faruq. He returned to Egypt from his studies in Britain on 6 May. At first, a Regency Council consisting of Muhammad Ali Tewfik, Adli Yakan Pasha, Tawfiq Nasim Pasha, Aziz Ezzat Pasha and Sherif Sabri Pasha assumed guardianship of the young king. On 29 July 1937, the council was dissolved and Faruq was declared fit to rule.

In the parliamentary elections of May 1936, the Wafd party again won a majority in parliament and Faruq, who like his father rejected the democratic order of the state, had to appoint Mustafa an-Nahhas Pasha as prime minister on 6 May. Nevertheless, there was some cooperation between the monarch and the government. Faruq announced a comprehensive reform programme at the beginning of his reign and entrusted Nahhas Pasha with its implementation. The government amnestied all participants in political protests arrested between 1930 and 1933, granted financial credit to all peasants and reduced taxes for all citizens. In terms of foreign policy, the government sought a balance with Great Britain. Nahhas Pasha resumed talks with the British and successfully negotiated a treaty that settled the dispute between the two nations that had been going on since 1924 and made them allies. Through the Anglo-Egyptian Peace Treaty of 26 August 1936, Britain relinquished certain reserved rights in Egypt and gradually withdrew its troops except for the Suez Canal Zone, while securing the right to access Egypt's transport and communications system in the event of war. In addition, the Egyptian army was placed under the supreme command of the King and the previous office of Sirdar was abolished, and instead of a High Commissioner, an ambassador was sent to Egypt as the British representative. On 14 November 1936 Miles Lampson (High Commissioner) and in 1937 Charlton Watson Spinks (Sirdar) had to vacate their posts and the Kingdom of Egypt was finally able to shake off British rule, although British influence remained considerable.

New foreign policy, full employment, eve of the Second World War

On 26 May 1937, Egypt joined the League of Nations and reoriented its foreign policy. It aligned itself with the Western democracies and once again moved away from the fascist Kingdom of Italy and the National Socialist German Reich, to which Egypt had increasingly aligned itself since 1933. Responsible for this was Mohamed Mahmoud Khalil, who was appointed the new prime minister by Faruq on 29 December 1937, after Nahhas Pasha had almost fallen victim to an assassination attempt by the Young Egyptian Party. Mahmoud maintained good relations with the British royal family and was a supporter of the Egyptian-British alliance of 1936. Under his government, Egypt condemned the annexation of Austria in 1938 and the previous Italian conquest of Ethiopia in 1935/1936. Tensions subsequently arose with Italy and conflict flared up again between the two countries over the final demarcation of Egypt's borders with the colony of Italian Libya. Italy also demanded that Egypt extradite supporters of the overthrown freedom fighter Umar al-Mukhtar who had fled to the country during the reconquest of Libya between 1923 and 1931. The Egyptian government refused and Italy erected a barbed wire enclosure 270 to 300 km long and four metres wide with fortified checkpoints on the border with Egypt.

The new course met with rejection from a considerable part of Egyptians. The Wafd party, which had been in opposition since Mahmoud's appointment, also rejected it. The ruling Liberal Constitution Party (حزب الاحرار الدستوريين, Ḥizb al-aḥrār al-dustūriyyīn), which split from the Wafd, was subsequently put under increasing pressure by Faruq and moderated its course again. Thus Egypt did not condemn the German-Italian intervention in the Spanish Civil War and kept a low profile in the occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1939. Nevertheless, Egypt had discredited itself in foreign policy terms with the later Axis powers as well as with the Western democracies, whose appeasement policy (above all the Munich Agreement of 1938) Mahmoud did not want to support, and only maintained good relations with the United States, which also made it possible to end the economic crisis in Egypt. Mahmoud relied on economic-liberal structural reforms and Egypt reached full employment again in 1937/1938. The liberal government also revived and continued the Wafd Party's modernisation programme, which had stalled in 1930 and was aborted in the turmoil of Ismail Sedki Pasha's dictatorship. The standard of living, especially in Cairo and the countryside, rose considerably thereafter. With an average per capita income of 1,300 US dollars, the country approached the European average. Whereby there were great differences between the north and south of the country. In today's Southern Sudan, there was no sign of the development and the majority of the population continued to live in poverty. In Khartoum, on the other hand, a comprehensive urban renewal took place on behalf of Faruq. Large parts of the city were demolished and numerous European architects were brought in for the redesign. Egypt was able to return to the international stage on 16 March 1939. The marriage of Faruq's sister Fausia to the Iranian crown prince and later Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi had created a strategic alliance between Egypt and Iran and Turkey. From then on, Iran supplied Egypt with extensive raw material supplies (especially oil), while Egyptian officials helped to build up Iran's then underdeveloped infrastructure. The alliance survived the Second World War and effectively lasted until the couple divorced on 18 November 1948.

On 18 August 1939, Mahmoud of Faruq was replaced by Ali Maher Pasha, who thus became prime minister for the second time. Ali Maher was also a member of the Liberal Constitution Party, but was critical of Britain and advocated permanent neutrality for Egypt. Nevertheless, like his predecessor, he condemned the Nazi Nuremberg Race Laws and offered persecuted German Jews a new home in Egypt. He tried to keep his country out of the burgeoning Middle East conflict.

Upper Egyptian-Libyan border as of 1926

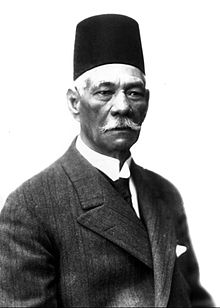

Saad Zaghlul, important social reformer and Prime Minister in 1924. In Egypt he is called Zaeem al Ummah (Leader/Father of the Nation).

Port Said, painting by Alexander Yakovlev 1927

Fu'ad I with the Belgian King Albert I and his wife Elisabeth Gabriele in Bavaria at Misr railway station visiting an industrial exhibition in Cairo, January 1930

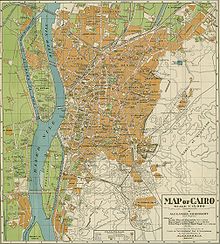

Modern city map of Cairo, 1933

The Shinnawi Palace in al-Mansura, built in 1928

Official portrait of King Faruq

The King after his enthronement in the Egyptian Parliament, 1937

A banquet at the Abdeen Palace on the occasion of the wedding of King Faruq and Queen Farida of Egypt. People photographed from right to left: Princess Nimet Mouhtar (1876-1945), Faruq's aunt (paternal); King Faruq (1920-1965), the groom; Queen Farida (1921-1988), the bride; Melek Tourhan (1869-1956), widow of Hussein Kamil; Prince Muhammad Ali Ibrahim (1900-1977), Faruq's uncle (paternal).

Prime Minister Mohamed Mahmoud Khalil reached a settlement with Britain during his second term until 1939

World War II

Neutrality and British occupation 1940

In September 1939, the Second World War began in Europe with the German invasion of Poland. King Faruq announced the general mobilisation of the army in the same month. The general staff under Aziz Ali al-Misri sent most of the units to the Libyan-Egyptian border in order to repel a possible Italian attack and possibly advance into the territory of the colony of Libya. However, the Italians were far superior in material and men to the only 100,000 Egyptian soldiers.

Italy finally entered the Second World War on the side of the German Reich after the Wehrmacht's successful campaign against France on 10 June 1940 and declared war on Great Britain and France. Benito Mussolini wanted to use the war to reestablish the Imperium Romanum around the Mediterranean and also laid claim to Egypt and Sudan. On 10 June 1940, the East African campaign began with Italian attacks on neighbouring British colonies. Egypt was thus drawn into the Second World War and Italian troops advanced into its territory. They occupied the now Sudanese towns of Kassala, Gallabat, Kurmuk and Qeisan.

On 13 June 1940, in response to the invasion, the Egyptian parliament broke off all diplomatic relations with Italy, but declared that it would remain neutral in the war. On 13 September, the same steps were taken towards the German Reich. On 28 June 1940, Ali Maher Pasha was dismissed as Prime Minister for refusing to break off relations with Italy. Hassan Sabry Pasha became the new head of government. Shortly afterwards, Britain invoked the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936, which allowed the occupation of the Suez Canal if it was threatened. The Egyptian army had nothing to oppose this. Faruq protested against the occupation but was stopped cold by the British. Protests by the parliament and the population were also ignored and partly suppressed. In Alexandria and Cairo, the British interned the Italian minority for sympathising with the enemy.

In August 1940, there were uprisings and protests against the British occupation policy. Italy used this as an opportunity to attack the seemingly unstable and militarily weakly defended country from the north in September, thus tying up the Egyptian-British troops in a multi-front war.

Invasion of the Axis Powers

→ Main articles: Italian invasion of Egypt, African campaign and East African campaign

After minor fighting on the Libyan-Egyptian border on 9 September 1940, with a series of air raids on British border posts, the Italian invasion of mainland Egypt began on 13 September. Benito Mussolini had demanded this advance from the Italian commander-in-chief in Libya, Rodolfo Graziani, in order to wrest the Suez Canal from the British, occupy Egypt and thereby link the Italian possessions in North and East Africa. The cautiously advancing Italians advanced within a few days to about 100 kilometres into Egyptian territory, where they halted and set up fortified camps due to the destruction of their supply routes by British aircraft and warships. There they collided with the top of the British forces in Egypt, whose headquarters were in Marsa Matruh. On 16 September, the town of Sidi Barrani was occupied, bringing the Italian hold on the country to its maximum.

On 14 November 1940, Prime Minister Hassan Sabry Pasha died. He was succeeded by Hussein Sirri Pasha, who was said to be sympathetic to the Axis powers. Nevertheless, he supported the British counterattack with Operation Compass, which began on 8 December 1940. On 10 and 11 December, Sidi Barrani was recaptured by British units. The Italian invasion of Egypt had thus failed. On 11 December, Rodolfo Graziani and his troops had to retreat to the Libyan-Egyptian border, where the British also arrived the next day and captured around 38,000 Italian soldiers. Within the next 10 weeks, they advanced about 800 km into Libyan territory, destroying 400 tanks, capturing 1292 guns and capturing about 130,000 prisoners of war.

During the entire Italian invasion of Egypt and the subsequent clashes from 9 September 1940 to 9 February 1941, the British and their allies lost only 500 men and suffered 1373 wounded and 55 missing. For the Kingdom of Italy, the enterprise was a disaster.

The news of the Italian defeat in Egypt and the unsuccessful attack on the Kingdom of Greece, which soon claimed the full attention of the Royal Italian troops due to strong Greek resistance, and the attack on Taranto in October 1940, forced Hitler to intervene. In February 1941, he sent the newly formed German Africa Corps under the command of Erwin Rommel to Tripoli, where it prepared to attack together with the Italians. On 31 March, the advance began, the main thrust of which was directed towards Marsa el Brega in order to be able to establish a bridgehead for the capture of the Kyrenaika. The German-Italian advance stopped in mid-April at the Egyptian border town and fortress of Sallum, east of Tobruk. On 10 April, the Afrika Korps launched the siege of Tobruk.

In November 1941, the Allies launched Operation Crusader to end the siege. The attack proved successful and after a complex series of battles they reached Berga on 6 January 1942. The siege of Tobruk finally ended on 27 November and the Axis forces withdrew from Cyrenaica up to and including El Agheila. King Faruq and the Wafd Party placed enormous expectations on the victory and sought to reintegrate the territories ceded to Libya in 1926 and 1934 respectively, but to no avail.

In November 1941, the British were also able to regain the initiative in East Africa. The fighting ended with the abandonment of Italian East Africa and freed Egypt from the grip of the two-front war. On the night of 18-19 December 1941, however, an attack was launched on Alexandria by combat swimmers from a special unit (Decima Flottiglia MAS) of the Italian Regia Marina on the base of the British Mediterranean Fleet. Six Italian torpedo riders grounded the two battleships HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Valiant with explosive charges. As a result of this attack, the balance of power in the Mediterranean shifted in favour of the Axis powers for several months.

In May 1942, the Afrika Korps launched Unternehmen Theseus. This offensive was able to push the British back as far as Egypt.

On 20 June 1942, the Axis forces attacked Tobruk again. The attack resulted in the capture of large quantities of fuel and ammunition. The British were unable to hold the city and surrendered on the evening of 21 June. A day later, Rommel again crossed the Libyan-Egyptian border, where he stopped on 24 June. On 26 June, the Battle of Marsa Matruh took place, where Rommel was able to capture the city on 29 June. The fall of Marsa Matruh was a great victory for Rommel. Now his troops were only 200 km away from Alexandria and captured important war material. On the same day, the small town of El Dabaa was taken, from where Panzerarmee Afrika was to advance on El Alamein (112 km west of Alexandria and 592 km east of Tobruk).

The first battle of El Alamein began on 1 July. The fighting lasted for about four weeks in July 1942 and ended with a British victory, because the British 8th Army concentrated mainly on weakening the Italian troops in order to weaken their German allies in the long term.

From the government crisis in 1942 to the end of the war

→ Main articles: State crisis in Egypt in 1942 and Egyptian declaration of war on the German Reich and Japan

In February 1942, when the Afrika Korps began a successful offensive towards Egypt, conflict broke out between the British and the Egyptian royal family for the first time since the death of King Fu'ad I in 1936. King Faruq wanted to reappoint the nationalist Ali Maher Pasha, who was hated by the British, as prime minister, but then decided to keep the previous government under Hussein Sirri Pasha in office. When the British government got wind of this, it called for the formation of a new government under Mustafa an-Nahhas Pasha of the Wafd Party to provide stability in the administration in the face of the African campaign. When Faruq tried to prevent the appointment of an-Nahas by postponing it, the British ambassador in Cairo Miles Lampson summarily had the king's palace surrounded by British troops with tanks on 4 February, whereupon Faruq relented. This act illustrated to the Egyptian military and the local population Faruq's powerlessness in the face of the British and severely damaged his reputation. But the Wafd Party, which had once again won an absolute majority in the March 1942 elections and had once been the standard-bearer of Egyptian nationalism, also became a symbol of collaboration with the British.

After the government crisis, anti-British and pro-German demonstrations and acts of sabotage took place in Alexandria and Cairo in early 1942. High-ranking officers, such as the general staff of the Egyptian army established secret contacts with the Italian and German staff. There were also numerous Axis sympathisers among the Egyptian elite around Faruq. Nevertheless, cooperation with the Axis was largely limited compared to other Arab countries. There were no boycotts directed against Jews, physical attacks did not occur and the practice of religion was not hindered. Moreover, Faruq refused to hand over the Egyptian Jews to the Axis in the event of victory.

The UK leadership successfully tried to pacify the Egyptian people as a result of the protests. The Wafd Party was then able to regain prestige and continued to be the dominant political force until it was banned in 1952.

From 23 October to 3 November, the decisive battle of El Alamein took place, ending in a British victory and leading to the capture of over 30,000 soldiers on 6 November. Bernard Montgomery, who had been appointed Commander-in-Chief of the 8th Army by Prime Minister Winston Churchill on 13 August 1942, was the commander of the British troops. The battle marked an important turning point in the Second World War and was the first major victory for British Commonwealth forces over the German army. Today, some historians believe that, with the Battle ofStalingrad, it was one of two major Allied victories that led to the total defeat of the German Empire in 1945.

After the complete withdrawal from Egypt, Libya also had to be abandoned by the Axis powers in January 1943. The defeat in the Tunisian campaign on 13 May 1943 also marked the end of the African campaign. Subsequently, from 22 to 26 November 1943, the Cairo Conference took place between the US Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and the Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. The three heads of government agreed on the Cairo Declaration on the war aims towards the Japanese Empire in the Pacific War.

Shortly before his fall on 10 October 1944, Mustafa an-Nahhas Pasha organised a meeting of representatives from seven Arab states in Alexandria in September. On 7 October of the same year, the founding of the Arab League was decided with the signing of the "Alexandria Protocol" (so-called Memorandum of Understanding). Further preparatory meetings were held in Cairo in February and March 1945. On 11 May 1945, the Kingdom of Egypt became one of the founding states of the League. The emerging Egyptian dominance (the seat of the organisation was in Cairo and the first Secretary General was an Egyptian, Abdel Rahman Azzam) led to increased tensions with Saudi Arabia.

An-Nahhas was succeeded by Ahmed Maher Pasha of the liberal-monarchist Saadian Institutionalised Party (حزب الهيئة السعدية). Under Maher Pasha, his party and Faruq were able to expand their popularity. In January 1945, the party obtained an absolute majority in the parliamentary elections by boycotting the Wafd Party. On 24 February, Mahir Pasha declared war on the German Empire and Japan. However, Egyptian troops did not take part in any combat operations and only flew reconnaissance flights against Italy until 1943. Shortly after the declaration of war, the prime minister was assassinated in parliament by a member of parliament, and on 26 February Mahmud an-Nukrashi Pasha was appointed as his successor as prime minister.

As one of the victorious powers, Egypt was visited on 13 February 1945 by Franklin D. Roosevelt visited. Other state guests were Ethiopia's Emperor Haile Selassie, Saudi King Abd al-Aziz ibn Saud and Winston Churchill.

The British battleship HMS Howe (32) with a felucca in the Suez Canal, 14 July 1944.

Faruq with ministers after the 1942 crisis

.jpg)

Cairo street scene during the war 1941

.svg.png)

Territories and Colonies of the Kingdom of Italy 1941

Ali Maher Pasha shortly before his release around 1940

Italian Advance into Egypt and the British Operation Compass

The post-war years 1945-1947

On 24 October 1945, Egypt, including Sudan, became a founding member of the United Nations and one of the first members of the UN Security Council. At the end of the same year, an anti-minority company law was passed by the parliament, according to which 75 % of all employees of a company had to be Egyptian (in a factory 90 % of the workers) and that 51 % of the capital had to belong to an Egyptian. As a result, many foreigners lost their assets. Their special jurisdiction was also abolished and all inhabitants of the kingdom were declared equal citizens, whereby the nobility retained its high social prestige and could continue to assert its dominant role in the military, diplomacy and higher civil administration. However, the reforms admittedly came too late; many young Egyptians were disillusioned after the war with parliamentary democracy, which was supposedly "managed" by the British, and with the inaction of the Egyptian political elite. Moreover, the war led to a deep economic and political crisis. The mass of the people had to cope with a rising illiteracy rate. Endemic diseases spread throughout the country and the health system collapsed. In addition, per capita income fell and unemployment rose. The large landowners (in 1952, about 4000 families, who made up only about 1% of the total population, owned 70% of the total arable land) also increasingly oppressed the peasants and minor famines occurred in the countryside. Foreigners also became impoverished and some emigrated. This created an atmosphere of rebellion and unrest. The first outbreak of violence was the Cairo pogroms of 2 and 3 November 1945, in which Egyptian Jews were excluded from Egyptian society for the first time since the founding of the kingdom. Although King Faruq condemned the events and, together with Prime Minister Mahmud an-Nukrashi Pasha, met with the Grand Rabbi Chaim Nahum of Egypt and Sudan, the events were not dealt with legally.

This was followed in November 1945 by a failed assassination attempt by the Muslim Brotherhood on an-Nahhas, the leader of the Wafd Party. In January 1946, a diplomat who had helped draft the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 was killed. On 9 February, an initially peaceful student demonstration ended in several deaths, and on 21 February, students and workers stormed a British barracks in Cairo, with 23 Egyptians shot dead by the British. The tense situation was fuelled by the Young Egyptian Party and Muslim Brotherhood. The two organisations looted numerous foreign shops, set fire to entire buildings, staged protests against the monarchy and carried out several terrorist attacks in Cairo and Alexandria. To put an end to the protests, Faruq Ismail appointed Sedki Pasha as head of government on 17 February 1946. Sediki thus took office for the second time and crushed the protests with police violence. He was thus able to restore a certain stability to Egypt.

During the unrest, foreign relations with the West increasingly deteriorated. In 1946, Egypt granted asylum to the former Mufti of Jerusalem Mohammed Amin al-Husseini, who was wanted as a war criminal in several European countries. In the same year, the country accepted the former King of Italy Victor Emmanuel III, who, after the end of the First World War, condoned the seizure of power by Benito Mussolini and the Fascist Party and the subsequent establishment of a dictatorship, which he maintained until 1943. In addition, the country did not impose economic sanctions against Francisco Franco's regime in Spain, although it had agreed to UN Security Council Resolution 4. British-Egyptian relations, which had been strained since the occupation of the country in 1940, also cooled steadily. Egypt demanded a renegotiation of the 1936 treaty and denied the British the right of access to the Egyptian transport and communications system as had been agreed in 1936.

A reception of Islamic revolutionary personalities in Cairo in 1947. The photograph shows, among others, Hasan al-Bannā, Aziz Ali al-Misri, Mohamed Ali Eltaher and other Egyptian, Algerian and Palestinian representatives.

A French stamp for Alexandria, 1946

Downfall

Defeat in the Palestine War, ban on the Muslim Brotherhood 1948, destabilisation of the government

→ Main article: Palestine War

On 14 May 1948, David Ben-Gurion declared the independence of the State of Israel on the basis of the UN Partition Plan for Palestine of 29 November 1947, which Egypt had rejected, when the British Mandate over Palestine officially ended.

King Faruq and the Egyptian government initially took a more conciliatory stance towards the new state. Fearing a coup d'état or a takeover by the Muslim Brotherhood, and in order to prevent the states of Transjordan and Saudi Arabia from gaining power, they decided, together with the other Arab states of Syria, Lebanon, Transjordan and Iraq, to form a military alliance and attack Israel without declaring war on 15 May. Faruq's goal thereafter was to annex the southern territories of the Palestine region. To this end, the Egyptian government sent an expeditionary force of about 20,000 men into the fighting. It consisted of five infantry battalions and one tank battalion. The regular units were supported by about 2,000 volunteers, mainly members of the Muslim Brotherhood who had already infiltrated the mandate area before the war began, and some Sudanese.

The commander of the Egyptian expeditionary forces, Major General Ahmed Ali al-Mwawi, planned two main directions of attack. The smaller part was to advance through the Negev Desert via Be'er Sheva towards Jerusalem. This advance reached Ramat Rachel on the southern outskirts of Jerusalem on 23 May and was only brought to a halt here by Israeli troops. Meanwhile, the second major part of the Egyptian forces advanced along the coast towards Tel Aviv, meeting determined resistance in the Jewish settlements on the way. This advance was also finally halted north of Ashdod. In the air and on the water, the initiative was also lost. The Royal Egyptian Air Force (REAF), which in May had still been bombing Tel Aviv with Sde-Dov airport en masse, lost many of its best pilots and numerous aircraft due to the deployment of effective Israeli air defence. The country's navy engaged in some minor naval battles with the new Israeli navy early in the war. By the beginning of 1949, however, their operational capabilities were largely exhausted, whereupon Israeli ships bombarded Egyptian coastal installations from Gaza to Port Said.

The final twist in the war came on 8 July 1948 at Kibbutz Negba, when Egyptian troops launched a pre-emptive strike on the village. Although neither side was able to gain a decisive advantage, the Egyptian army was effectively depleted thereafter and suffered increasingly from a lack of ammunition. In October, the country still tried to impose a blockade, but this failed on 15 October with the destruction of the airfield at El-Arish by Israeli air forces, and considered the use of mustard gas as a last resort. On 22 October, Israeli troops finally advanced into Egyptian territory, whereupon the British government under Prime Minister Clement Attlee intervened and forced Israel to withdraw from Egypt. On 6 January 1949, the last Israeli soldiers left Egyptian soil.

On 24 February, a ceasefire agreement was signed between Israel and Egypt in Rhodes, in which the country officially withdrew from the war. Egyptian troops then withdrew from the Negev Desert, retaining control only over what is now the Gaza Strip, where an "Arab government for all Palestine" was proclaimed by Mohammed Amin al-Husseini on 22 September 1948, but completely dependent on Egypt. The other Arab states followed Egypt's insistence on a ceasefire agreement and gradually gave in. On 20 July 1949, the Palestine War ended.

Despite relatively favourable ceasefire conditions, the Egyptian defeat had enormous consequences for the country. In foreign policy, Egypt was discredited as the most powerful Arab country and could not prevent Jordan (which annexed the West Bank) and Saudi Arabia from gaining influence. Domestically, the unrest of 1946/47 flared up again. In a renewed wave of violence, Jews were targeted by targeted bombings and their businesses destroyed in June and July 1948. The European inhabitants of Alexandria and Egyptian Christians also became targets of the Muslim Brotherhood's terror. The riots continued to some extent until 1952 and claimed several hundred lives, including 70 Jews.

The government's response to the pogroms and the growing influence of the Muslim Brotherhood came with its ban on 8 December 1948. The government of Mahmud an-Nukrashi Pasha suspected that the Muslim Brotherhood was planning a revolution and considered them a threat to the ruling elites. Moreover, the Brotherhood had its own hospitals, factories and schools, which were subsequently nationalised. The state also confiscated their considerable assets. This was followed by a brutal wave of repression from the government. From 1948 to 1950, tens of thousands of Brotherhood members were arrested and many of them were tortured or murdered in prisons. In November 1948, 32 prominent Brotherhood leaders were arrested and the organisation's spiritual leader Hasan al-Bannā, after living under close police surveillance for months, was shot dead in Cairo on 12 February 1949 by order of the royal family.

Despite brutal reprisals and the institutionalisation of strict press censorship, the Egyptian government was severely destabilised by the unrest and largely lost control of the country. In March 1948, the Muslim Brotherhood assassinated Judge Ahmed El-Khazindar Bey and, on 28 December, Prime Minister Mahmud an-Nukrashi Pasha. An assassination attempt on his successor, Ibrahim Abdel Hadi Pasha, failed. There were also repeated violent attacks directed at the police and strikes by workers and peasants. It marked the beginning of the decline of the kingdom, culminating in the 1952 revolution.

Nationalism in transition

The defeat in the Palestine War exhausted the ideology of Egyptian nationalism that had prevailed until then and briefly led to the loss of Egypt's hegemonic power in the Arab and Islamic world. Arab nationalism and pan-Arabism, which had emerged in the course of the general emancipation of the colonial peoples and aimed at unifying the Arab countries, became an acceptable alternative for many who, disillusioned with Egyptian nationalism, were looking for an ideological complement. Ideological emphases also began to shift and the democratic element lost weight in favour of left-revolutionary and republican ideas. One example was the formation in 1949 of the so-called "Free Officers Movement", a group of armed army officers led by Muhammad Nagib and Gamal Abdel Nasser. A momentous element of the new nationalism, however, was the suppression of ethnic minorities such as the Copts, Jews and Europeans that began afterwards. Religion also played an increasingly important role. In the provinces of southern Sudan, for example, an increasingly ruthless aggressive Arabisation and Islamisation was pursued, which ultimately deprived the monarchy of the complete support of the population in the black African areas.

When the Arab League was founded, it was also decided to boycott the Yishuv, the Jewish settlements in Palestine, from 1 January 1946. Prominent Islamic clerics, such as the Grand Mufti al-Husseini, aggressively campaigned for the expulsion of all Jews from Palestine, thus also fuelling Arab nationalist sentiment directed against Israel as an enemy. Egypt played a pioneering role in the Arab League's boycott of Israel from 1948 to 1979.

Another sign of rising nationalism was the general effort to renegotiate the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty. The aim was to get the British forces to leave completely or at least to reduce their numbers. However, the British were determined to station at least 80,000 troops around the Suez Canal Zone.

The Egyptian-British negotiations began in 1946, with Faruq sending Prime Minister Ismail Sedki. When he returned from the negotiations in London with a draft treaty that the nationalist groups branded absolutely unacceptable, pressure from the street led to the resignation of the government in December 1946, already demonstrating the powerlessness of the monarchy. No agreement could be reached under subsequent governments either.

On 8 October 1951, the Egyptian parliament under Prime Minister Mustafa an-Nahhas Pasha unilaterally denounced the 1936 treaty, triggering mass demonstrations in support of Egyptian independence and providing the monarchy with one last remedy. Egypt was thus able to fully free itself from the British sphere of influence, although its foreign policy nevertheless remained pro-Western to a certain extent. In particular, proximity to the former colonial powers Italy, France and Great Britain was sought.

On 16 October 1951, in order to further fuel nationalism and restore popular support for the monarchy, Faruq accepted the title of King of Egypt and Sudan offered to him jointly by the Egyptian parliament, an-Nahhas Pasha's government and senior Sudanese dignitaries, which until then had only been the unofficial title of Egyptian monarchs. At the same time, he denounced the Anglo-Egyptian condominium and demanded that British troops withdraw from Sudan. Britain refused and the condominium was effectively allowed to continue until 1956. The coronation of Faruq proved advantageous domestically and brought renewed support for the Egyptian monarchy. In Sudan, the unionist forces were additionally won over to the project and monarchism was also strengthened there. In foreign policy, however, this step led Egypt even further to the sidelines. Many countries protested against it or did not even recognise Faruq's new claim to power and called on Egypt to grant the Sudanese the right to self-determination.

The defeat in the war also led to a decisive strengthening of Sudanese nationalism, which had already developed after the First World War and had its carrier base in the northern provinces of Sudan. The nationalists now sought a breakaway from Egyptian-British rule and advocated a centralised republican national government in Khartoum.

The first Sudanese nationalist movement was founded in 1921 by the Muslim Dinka Ali Abd al Latif. It fought for an independent Sudan in which power would be shared by tribal and religious leaders. In 1924, presumably as a protest against Egyptian independence, it organised large-scale demonstrations in Khartoum. Ali Abd al Latif was then arrested and subsequently exiled to Egypt. A subsequent mutiny by a Sudanese army battalion was crushed and the movement briefly paralysed by the brutal repression of the colonial rulers.

In the 1930s, nationalism emerged more strongly in Sudan, as in Egypt. The most popular demands were to limit the power of the British governor-general and for Sudanese participation in political life in Egypt, where almost exclusively purely Egyptian parties were represented in parliament. However, such a change required the consent of the British government and the Egyptian king. Neither Britain nor Egypt agreed to the change, as both countries feared a reduction in their influence vis-à-vis the other power. Moreover, the British considered themselves as the protecting power of the opponents of a unification of the whole of Sudan with Egypt. The nationalists feared that as a possible consequence of the constant friction between the condominium forces, Sudan would be divided and northern Sudan would be added to Egypt and southern Sudan to the protectorate of Uganda or British Kenya. Although the 1936 Treaty of Alliance removed most of the conflicts and set a timetable for the end of British military occupation, negotiations over the future status of Sudan failed. The treaty also led to increasing tensions between the unionists and their opponents. While Sudanese cleric and Muhammad Ahmad's son Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi advocated independence under him as the self-proclaimed "King of Sudan", in the early 1950s the young leader of the Islamic order Khatmiyya Ahmad al-Mirghani placed himself at the head of the proponents of unification. The two leaders and their political camps fought each other, especially after Faruq's proclamation in 1951, with unofficial support from Britain and Egypt respectively. However, the nationalist, independence-seeking groups proved to be much more radical.

Beginning of the Cold War and decolonisation

Among the countries that did not recognise Egypt's claim to rule in Sudan was almost all of Western Europe and the United States and the Vatican. Thus, at the beginning of the Cold War, Egypt finally had the USA and Great Britain against it. Although King Faruq and the Egyptian government repeatedly affirmed the saturation of the nation, Egypt's policies did not seem quite predictable to these states. Moreover, the US government under its President Harry S. Truman considered Egypt to be an extremely corrupt and unstable country that could easily fall under Soviet influence. To prevent this, "Project FF (Fat Fucker)", aimed at overthrowing King Faruq, whose authoritarian style of government they were mainly disillusioned with, and installing a pro-Western republican government led by the Free Officers Movement, supported by both the Americans and the Soviets, was developed by the Central Intelligence Agency. It was initiated by Kermit Roosevelt Jr. and Miles Copeland Jr. but never implemented.

In September 1947, Egypt officially asked the US Embassy in Cairo for help in training the Egyptian armed forces. However, the request was rejected.

Despite a relatively non-aligned foreign policy, there was a great fear of communism and Stalinism among the Egyptian elite. In particular, the rapid succession of communist takeovers in Eastern Europe from 1944 and in China after the civil war in 1949 forced Egypt to practice its own containment policy, which was modelled on that of the USA and aimed at containing communist expansionist policies in the Arab and Islamic regions. In the Greek Civil War between communist insurgents and the royalist government, Egyptian authorities interned communist-minded Greeks of the local minority and Greek prisoners of war deported from Greece. Allegedly, the Egyptian general staff even offered to deploy ground troops.

Due to the economic crisis of 1946, communism had also gained strong support inside Egypt. Especially the urban working class and the younger generation of Egyptians had communist sympathies. The government, still weakened by the Palestine war, therefore asked the Muslim Brotherhood for help and hoped to turn it into an anti-communist bulwark. In return, the Brotherhood was rehabilitated in 1950 and most of the prisoners were released. The Young Egyptian Party was also supported and its supporters carried out armed "punitive expeditions" against "red" trade union houses, newspaper editorial offices, workers' homes, cultural houses, cooperatives and individuals. After some time, the more than 20 different small socialist and communist parties and organisations had already been largely eliminated as a political factor. In addition, trade unions were massively losing members and influence. The only major "red" party that withstood the unofficial state terror was the Democratic Movement of National Liberation (الحركة الديمقراطية للتحر الوطنى), founded in 1947, whose membership in 1952 was around 2,000-3,000, making it the largest communist organisation in Egypt and the Arab world. It also sought a revolution to overthrow the monarchy and was therefore persecuted. Nevertheless, the party could never really develop into a real threat to the royal house.

Due to some reports from foreign Egyptian communists, the Soviet Union became aware of Egypt from 1950 onwards. Although it also railed against the owning class in Egypt, it nevertheless sought political solidarity.

In 1950, the Soviet dictator Josef Stalin commissioned the construction of the Mogamma, today's Egyptian Central Administration Building, and offered development cooperation. The motive could be seen as being able to exert considerable influence on Egypt and its region and to link the kingdom to the Soviet system of rule. However, Egypt refused, thus making it more difficult for the Soviet Union to build long-term relations and instead concluded a non-aggression pact with it. At the same time, however, although the kingdom had not recognised the overthrow of the Yugoslav monarchy, it maintained good relations with Yugoslavia under Josip Broz Tito, who was also non-aligned and hated by Stalin. Egypt had thus established itself as a non-aligned power in the beginning Cold War, a policy that is still maintained today.