Khasi people

![]()

This article is about the people - for other meanings, see Khasi (disambiguation).

The Khasi - proper name Ki Khasi ("Those Born of a Woman") or Ki Khun U Hynniewtrep ("The Children of the Seven Huts") - are an indigenous people in northeastern India with over 1.4 million members in the small state of Meghalaya in the foothills of the Himalayas; they form about half of the total population there. About 35,000 Khasi live in the neighboring state of Assam and about 100,000 in Bangladesh, which borders to the south. The Khasi form a matrilineal society through matrilineal lines, in which descent, surname, and succession are derived only from the mother, not the father. These relationships are enshrined in the Meghalaya constitution, including for the neighbouring matrilineal Garo people; both created the state in 1972, the Indian constitution guarantees them special rights of protection and self-government as "Scheduled Tribes". According to Khasi tradition, ownership of land is in the hands of women only; it ensures social and economic independence and security for mothers and their extended families. Men belong to their mother's extended family, inherit the family name and clan affiliation from her, and contribute to her maintenance; they are part of the solidarity community, but usually cannot inherit land. After marriage, the husband usually moves in with his wife and her mother (matrilocal order of residence), and his children will belong to their extended family. The wife's brother is considered her protector and advisor and will traditionally take care of her children as a social father (avuncular of the mother's brother).

Most families practice traditional crop cultivation with animal husbandry as a subsistence economy and trade with harvest surpluses on the weekly markets of the approximately 3000 Khasi village communities; men are almost always designated as village chiefs. Families that belong together form associations (clans) that have elected leaders (chiefs) in addition to their clan mothers. The 3363 clans of the Khasi tribes, some of which are very large, organize themselves politically as a tribal society, subdivided into 64 clan chiefdoms. The original origin of the Khasi is believed to be east, in the area of the Mekong River (see below), because the Khasi language in no way resembles the neighboring Indian languages. The Khasi are 83% Christians of various churches, but besides that they maintain their traditional animistic religion Niam Khasi with ancestor worship and sacred forests as well as their own egg oracle. Some Khasi villages became world-famous for their large root bridges made of living rubber trees (see pictures).

Economy of the Khasi

Most Khasi extended families (iing) operate in the manner of a family business and form overlapping associations in the manner of agricultural cooperatives, especially in village communities (see above). Around 1800, documents from the British East India Company describe the Khasi as a very experienced market-oriented people, with a stable economy consisting of the three elements of land ownership, field work with production, and trade in the many local markets.

Many families practice subsistence farming and use various types of traditional field cultivation (planting), in addition to manageable livestock farming with a few pigs, native cattle, goats, chickens or bee colonies and perhaps a small village shop. The main food of the Khasi is cooked rice, vegetables and eggs, meat or (dried) fish; pulses and nuts are not common. There are some food taboos, so no cow's or goat's milk may be drunk. Vegetables are mainly potatoes, sweet potatoes, cabbage and increasingly tomatoes; fruits are mainly the sweet Khasi mandarins, pineapples and bananas, distributed in different altitudinal regions. On the high plains, the kitchen gardens with vegetables, spices, medicinal plants and orchids are protected by small ramparts and hedges. There are a few villages here with small-scale industries such as knife smithies, otherwise very little industrial production is found in the Khasi area. The spread of the sewing machine has enabled the mass production of home-made garments, but increasingly cheap plastic goods are also displacing traditional weaving.

Land ownership

All land in a village and its individual extended families is regulated in the manner of a cooperative or cooperative and managed by the village community or its village council: There are about 30 different types of land ownership in a village, some involving commons and common land (village land) or collective and joint ownership, other land being inherited only within individual family lines (see below), and others involving newly developed or privately acquired land. Over centuries, locally different systems with stable traditions have developed to ensure the well-being of the resident families and to keep together the basic economic base for the whole village (compare agrarian community). All villagers have equal access to cultivate the community land (for self-sufficiency), not differentiated by social standing or wealth. The village community may lease land or use rights to outsiders (transfer for use), for example for a private plantation or animal farm or for mining. In Meghalaya, about 82% of all houses were owned in 2011, and only 16% were rented out. A government study of land ownership by private households in India in 2003 found that Scheduled Tribes (tribal people) had slightly more households owning land than the India-wide average, and that each tribal household owned slightly more land than the average (0.70 hectares at 0.56 per household).

Conflicts:

- With regard to community land, a comprehensive study from 2007 on the question of social security within the tribes of Meghalaya came to the conclusion that the treatment of Khasi land is changing noticeably: Increasingly, shares of village and family land are changing to private ownership, with Khasi men in particular becoming new landowners (non-indigenous people are prohibited from buying land in Meghalaya). This weakens the economic basis of the families and villages, in addition to the overuse of the remaining communal land (compare tragedy of the commons - tragedy of the anti- commons). Many families find themselves forced by privatization to move to less productive land, which in turn exacerbates the harmful effects of their slash-and-burn farming (see below). Women, as owners of the (family) land, face increasing social insecurities; increasingly, women are also unable to provide a desired husband with social security to start a family, which in turn increases men's desire to own land. The proportion of land ownership among the 705 Scheduled Tribes in India has also declined: in 2001, 45% of tribesmen worked on their own land, whereas in 2011 this figure was only 35%, while the proportion of tribesmen working on land belonging to others remained the same at 46%.

Fishing

In the southern foothills of the mountain ranges, the monsoon waters run off in numerous small and larger rivers, at times forming crystal clear lakes, and the network of water bodies is very rich in fish and species. Village communities have always set binding rules for their area, setting fishing quotas and imposing fishing bans during spawning seasons to preserve the sustainability of their community's economic base. Meghalaya's government has set up support programs for this purpose and banned chemical and blasting tools that have been used elsewhere.

In the southern Khasi Mountains, the Khasi tribe of War uses its own traditional methods of fishing for self-sufficiency, with techniques and jigs for different types of water, seasons and animals. For the War, edible fish and other aquatic animals are the main source of their protein, along with meat; if the catch is dried within hours, it can be stocked for several days. Edible aquatic plants are also collected or harvested at the appropriate time. There are six different plants used to stun animals, for example, a juice of berries poisonous to fish is put into the running water of a stream, then the stunned fish are collected downstream (compare fishing with plant poisons). Eleven plants are used as bait for various types of catches, bamboo baskets woven in different ways are used as fish traps, and some species of frogs are caught. These traditional and cooperative forms of management conserve fish stocks and have been shown to maintain the biodiversity of the many water bodies.

Fieldwork

The Khasi Mountains consist of many ranges of hills with a large plateau at 1500 m, intersected by valleys and gorges, on which Shillong is also located. To the south, this open, very humid plateau drops steeply towards Bangladesh, accompanied by many waterfalls. For up to nine months between March and November, tropical monsoon rains drench the wet and rain forests of the mountains and hills. The jungles merge into extensive areas of shrubs and bushes, and on the plateau there are smaller grassland areas.

The Khasi cultivate four different types of land:

- extensive forest and jungle areas in the hills for gathering, traditional agroforestry and shifting cultivation

- local grasslands on the plateau, mainly for maize and millet (food crops for self-sufficiency)

- moist land, mainly for private rice cultivation, mainly in the southeast neighbouring Jaintia area (cash crops for sale)

- small field and kitchen garden areas near the residential house for mixed cultivation (diverse fruit, vegetable, spice and ornamental plants)

Accordingly, the village communities have specialized in the cultivation of their respective natural environment and have developed differences in way of life and traditions, up to their own language dialects (compare ecosystem people). At the same time, the diversity of cultivation has led to the intensive trade exchange even between distant villages, which forms one of the three pillars of the Khasi economy (besides land ownership and field work).

Conflicts:

- There is a continuing population explosion in Meghalaya (annual increase over 2.5%), with the total population growing from 1.33 million in 1981 to nearly 3 million in 2011 (+122%). This led to major problems early on because available arable land in the mountainous and hilly areas is limited; it is hard to develop more and provide new jobs. Although agriculture accounts for 70 % of the total economy, more and more Khasi families are unable to obtain (new) land ownership; their relatives have to seek their fortune in wage labour, usually low-paid. As early as 2001, poverty had increased significantly throughout Meghalaya, against which the government set up appropriate support programmes; in 2011, 11% of the total population lived below the statistical poverty line. The rate of population growth in the six Khasi administrative districts was in line with the national average of nearly 3% per annum, with 78% of Khasis living in rural areas; the Khasi share of the population had fallen to 48% from 56% in 2001 (see population data table). By 2020, Meghalaya's population is expected to grow to 3.77 million.

Broom grass

In the mountains and hills grows the "broom grass", a sweet grass of the species Amriso (Thysanolaena maxima), which can be found up to altitudes of 1800 meters and holds together the most diverse soils with its dense root system. Amriso is also being promoted by the International Climate Initiative (IKI) as an adaptable plant with a promising future. The German Environment Ministry is supporting an initiative in the nearby mountain state of Nepal, which is similarly threatened by landslides and frequent earthquakes. The harvesting, planting and sale of broom grass has been promoted by the Meghalaya government since 1995, after the corresponding products were presented at a trade fair in India's capital and were in great demand. In 2000, an initial survey shows that 40,000 families benefit from broom grass and its processing. Although the buying middlemen earn an equal amount from the products, broom grass allows families to earn extra money, especially in the low-income winter season. It also provides an alternative to damaging shifting cultivation (see below) and is increasingly grown in plantations, as cash crops for sale. Widespread is the traditional (art) craft of broom-making, which entire Khasi villages pursue, selectively cultivating various suitable plants for this purpose. Throughout India, 250 million households buy two new brooms a year, preferably made of broom grass.

Slash-and-burn

In the forested hills, Khasi farming practices involve alternate slash-and-burn cultivation to obtain new land for cultivation (shifting cultivation), commonly known in Asia as jhumming (compare the Jumma tribes) or slash-and-burn cultivation. For this purpose, at the beginning of the four-month dry season in November, the whole village community decides to clear a limited area, sometimes an entire hilltop or hillside. Usually the areas are on steep hillsides. All vegetation is lopped off and left for a few weeks to dry out in the sun before the remains are burned in a controlled manner. The remaining trees and rootstocks are also set on fire. The ashes provide minerals to the soil and make it more fertile. Without ploughing beforehand, the seeds are sown at the beginning of the new rainy season in March, eliminating the need for irrigation. Cultivation by individual families follows the division of the land as determined by the village community. Normally, an area is used with annual rotation of crops for three or four years, then it remains fallow land for various slow-growing crops and a new jhum area is developed ("shifting cultivation"). 40% of Meghalaya's land is under shifting cultivation.

Jhumming requires many hours of labour, the effort can only be made collectively; in Meghalaya, around 52,000 families depend on it. For centuries, this method of cultivation has preserved the protective plant cover of the hills and mountain sides because village communities did not want to "exploit" their own lands, but to cultivate them sustainably. Shifting cultivation is seen as an optimal indigenous adaptation to the hill areas affected by the heaviest monsoon rains to grow purely organically a diversity of crops for self-sufficiency (sometimes up to 30 at a time). Slash-and-burn cultivation is generally declining because its yield is diminishing, as the damage caused has a lasting impact on the overall habitats (biomes) of the village communities.

Conflicts:

- The time intervals between slash-and-burn operations at the same site used to be 15 years or more, during which the soil and its protective vegetation could recover - increasingly the intervals are shortening, sometimes to less than 5 years. For decades, this overexploitation has led to severe erosion of the soils (soil degradation) because there is no vegetation to protect the soil and store the monsoon rainfall; the run-off water washes the fertile topsoil downhill, while other watercourses seep away. To counteract this, university-trained Khasi have successfully introduced new farming methods, including stationary terrace farming. The government programs mainly recommend a change from shifting cultivation to plantation cash crops for sale, for example broom grass, which can hold together even eroded and depleted soils with its strong root system and produces a lot of biomass very quickly. Plantation cultivation, however, requires a fundamental change from traditional, mixed cultivation methods to monocultures, with all the known disadvantages such as high investment costs, the inevitable use of chemical fertilizers and poisons, and the loss of self-sufficiency. Increasing plantations also do not replace the needed protective plant cover and prevent opportunities for traditional mixed agroforestry. In addition to cash crops, the government supports the establishment of protected areas and sacred forests along the lines of the Khasi (see above).

- Particularly affected by deforestation are the adjacent Garo Mountains to the west, where international projects with alternatives to slash-and-burn are underway with the willing participation of the village communities. In the Garo Mountains, the wildlife suffers most, the number of wild elephants has dropped to less than 1000 (in 2008 there were still 1811 elephants in Meghalaya), the number of gibbon apes has more than halved. Here, the matrilineal Garo are adopting the Khasi tradition of natural forest reserves; these are also to ensure the elephants' migration corridors.

Trade

At the beginning of the British East India Company's influence from 1750 onwards, the Khasi were still engaged in extensive trade with their neighbouring peoples, as far east as Cambodia - their Mon-Khmer language is related to Cambodian, from which direction their original origin is also assumed (see below). Some time later, as part of their advancing conquests, the British imposed a comprehensive boycott on all Khasi goods, which led to growing resistance from the chiefs in the border areas. In peace negotiations beginning in 1860, the chiefdoms were granted tax exemptions and self-government, and the Khasi's extensive trade flourished again. The British colonial masters were impressed by the Khasi's economic and trading skills, but they depended on cross-border exchanges. Even today, almost all Khasi extended families trade in crop surpluses or specially made products, act as middlemen or intermediaries, or run a shop.

Conflicts:

- The nationwide Khasi trade is limited in the south by the basically closed border with Muslim Bangladesh (420 km long); there, too, some 100,000 Khasi live in the large district of Sylhet. Until 1971, an extensive trade network spanned between the Brahmaputra River in the north, the Khasi mountains and the large area of the Ganges in the south, mainly via markets along the main trunk road between Calcutta via Shillong to Guwahati, still built by the British occupiers (compare National Highway 40). The Third Indo-Pakistani War brought this network to a halt. In 1972, the state of Bangladesh seceded and became independent, border traffic was hardly possible any more, and the whole of northeast India was cut off from access to the Indian Ocean. For decades the exchange of goods remained difficult, the Khasi could no longer trade their coveted Khasi mandarins (origin species), betel nuts (areca nuts) and betel leaves (paan) as well as their rich mineral resources (coal and limestone) to the south. Although the border remains impermeable, around 90% of Khasi mandarin exports went to Bangladesh in 2015, while trade links to northern India are generally weak, with only a narrow bottleneck through West Bengal.

- The rich uranium deposits in the southwestern Khasi mountains (9 million tons) are beyond their trade because the valuable metal is exploited only by the Indian government, without any influence on the part of the authorities (India is a nuclear power). This state of affairs, as well as the widespread environmental damage caused by toxic uranium mining, has become a public issue in Meghalaya, with the three main Khasi organisations also using ethno-centric arguments under the rubric of "alienation" (see below). In 2018, the dispute over illegal coal mining in the form of "rat-hole mining" in Khasi territory is also playing an important role in the election and subsequent formation of a new government (compare coal mining in Meghalaya).

Weekly markets

Markets are held alternately in the many villages, on a marketplace prepared for this purpose at the edge of the village near the memorial stones that have been erected. The frequent weekly markets, in addition to the economic, also fulfill important social functions, they allow the constant exchange of information, serve as a marriage market and sometimes organize sports competitions. The most popular of these is archery, of which the Khasi are particularly proud of their distinctive tradition (see below on archery). The largest market is located in the middle of the Khasi region in the capital Shillong (at 1500 m): Police Bazar occupies a whole quarter, is open daily and attracts visitors and traders from the wide plateau and the surrounding Khasi mountains.

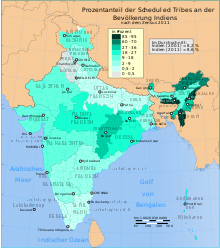

Gender data

Meghalaya is the only (federal) state in the world with an officially matrilinealsociety (matrilines), both the Meghalaya government and the Union government of India emphasize this matrilineal society, whose matrilineal descent rule and family affiliation is enshrined in the constitution. The Khasi accounted for 47.6% of the total population in 2011, while the Garo accounted for 27.7% (75.3% combined). Both are recognized as Scheduled Tribes and together constituted 87.4% of the 17 tribal peoples in Meghalaya, which in turn constituted 86.2% of the total population; there were a total of 705 recognized Scheduled Tribes in India in 2011, accounting for 8.6% of India's population (1,210,855,000).

The following lists from 2011 compare data from Khasi, Garo, Meghalaya, Scheduled Tribes and all of India - broken down by women and men and their shares in the total group. For example, literacy: 77% of Khasi can write, compared to 79% of females (of all ♀ aged 7 and above) and only 76% of males (of all ♂ aged 7 and above); there are 448,600 female alphabets and 411,200 male alphabets, so the total is divided into 52.2% females and 47.8% males: 4.4% more Khasi females than males can write. This division is calculated below for employment rates, gender distributions and literacy rates. Various measures of wealth and gender equality are then listed.

Employment rate

Nowadays, Khasi are increasingly pursuing a modern occupation or studying at one of the ten universities, such as the North Eastern Hill University in Shillong (population about 150,000), which was founded in 1973. Their families continue to keep some animals for self-sufficiency and cultivate their own garden areas (horticulture). Since 82% of all houses in Meghalaya are self-owned and all villagers have equal rights to use the common land (see above), this results in only a low official unemployment rate of 4.8%. Living below the poverty line in Meghalaya in 2012 was 11.9% of residents (less than 890 Indian rupees monthly in rural areas or 1150 in urban areas), compared to 21.9% India-wide (816 rupees monthly in rural areas, 1000 in urban areas).

In 2011, the official employment rate in India calculated the ratio of the number of employed persons (workers) to all other residents:

| Employment rates 2011 | |

| Khasi (48% of the population, 55% of the tribes) | Garo (28% of the population, 32% of the tribes) |

| 0rr 40,2 %, of which 59 % in agriculture

| 0rr 40.0 %, of which 72 % in agriculture

|

| Scheduled Tribes in Meghalaya (86 % of the population) | ST in India (705 recognised: 9 % of total population) |

| 0rr 40,3 %, of which 64 % in agriculture

| 0rr 48,7 %, of which 79 % in agriculture

|

| Meghalaya (3 million inhabitants) | India (1.21 billion inhabitants 2011) |

| 0rr 44.3 % (2001: 49 %) ... % of women:' ... ... | 0rr 39,8 %, of which 55 % in agriculture

|

The employment rate of Tribes in Meghalaya was the 4th lowest among the 29 states in India at 40%.

Globally, the rate calculates the proportion of employed persons out of all employable persons aged 15-64, in 2018, the average of the 36 member countries of the OECD was 68.3% (60.8% for women and 76.0% for men), in India in 2012: 53.3% = 27.3% for ♀ and 78.5% for ♂ (compare India in the list of global employment rates).

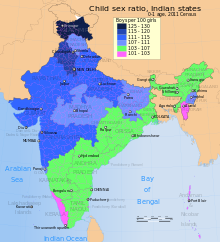

Sex ratio

The sex ratio in India in 2011 was officially calculated by the number of females to 1000 males; for the Khasi this was 717,000 ♀ to 695,000 ♂ = 1033 females to 1000 males. The Khasi have no relation to the sex preference practiced by aborting female embryos in much of India and China - this is shown by the number of girls under 7 years of age in relation to 1000 boys (together 21%):

| Sex ratios 2011 (2001, 1991) | |

| Females per 1000 males | Girls per 1000 boys (together ≈ 20 %) |

| 1033 ♀ among the Khasi (1017) | 971 ♀ with the Khasi (979) |

| 0988 ♀ with the Garo (979) | 976 ♀ with the Garo (...) |

| 1013 ♀ at Scheduled Tribes in Meghalaya (1000) | 973 ♀ at Scheduled Tribes in Meghalaya (974, 991). |

| 0990 ♀ at Scheduled Tribes in India (978) | 957 ♀ at Scheduled Tribes in India (972, 985). |

| 0989 ♀ in Meghalaya (972; 1901: 1036). | 970 ♀ in Meghalaya (973, 986) |

| 0943 ♀ in India (933) | 914 ♀ in India (927, 945) |

| 0984 = global average | 935 = global average |

Meghalaya was ranked 6th in India in 2011, with Kerala ranked 1st with 1084 females to 1000 males; for children, Meghalaya was ranked 2nd with 970, behind Arunachal Pradesh with 972 girls to 1000 boys.

Globally, the sex ratio of males to 100 females is measured, in 2015 it was 102 ♂ (107 ♂ babies to 100 ♀), in India: 107.6 males, at birth: 110.7 boys per 100 girls.

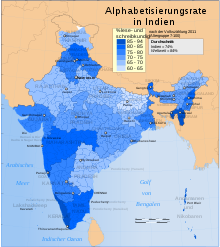

Literacy rate

Reading ability was calculated in India in 2011 for all persons aged 7 years and above. Among the Khasi, the 3% higher rate of reading ability among females compared to males (4.4% more females can read) clearly stands out from the countrywide and India-wide gender differences. The rate shows how much girls' schooling is valued among the Khasi - also in contrast to the neighbouring matrilineal Garo, among whom there is a particularly balanced gender ratio (50.3% of the 820,000 Garo in Meghalaya are male), but 6.4% more men than women can read, and the female literacy rate is 8.4% lower than the male literacy rate:

| Literacy rates 2011 (2001) | |

| Khasi (48% of the population, 55% of the tribes) | Garo (28% of the population, 32% of the tribes) |

| 0rr 77.0 % (66 %) ♀ 78.5 % of women:' 52.2 % of alphabets | 0rr 71,8 % (55 %)

|

| Scheduled Tribes in Meghalaya (86 % of the population) | ST in India (705 recognised: 9 % of total population) |

| 0rr 74,5 % (61 %)

| 0rr 59.0 % (47 %)

|

| Meghalaya (3 million inhabitants) | India (1.21 billion inhabitants 2011) |

| 0rr 74.4 % (63 %; 1951: 16 %)

| 0rr 73.0 % (65 %; 1951: 18 %)

|

Globally, literacy is measured from 15 years of age, it was 86.3% in 2015 (82.7% for females and 90.0% for males), in India: 71.2% = 60.6% for ♀ and 81.3% for ♂ (compare India in the list of global literacy rates).

Indexes

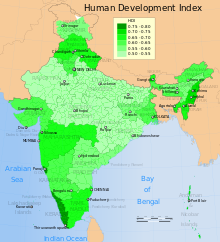

Human and gender development

As a comparative measure of well-being and gender equality in the countries of the world, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) calculates several statistical indices (indicators with values ranging from a low of 0.001 to an optimal 1.000) each year:

- HDI Human Development Index = average life expectancy, years of schooling and purchasing power per capita (officially from 1990)

- GDI Gender Development Index "Index of gender-specific development" = HDI values of women and men in relation to each other (officially from 1995)

- GEM Gender Empowerment Measure "Women's Participation Index" = political and economic participation and income, by gender (1995-2014).

- GII Gender Inequality Index = women's reproductive health, proportion of women in parliament, and schooling and labour force participation by gender (as of 2010)

Both the Meghalaya Government (Planning Department) and the Union Government of India (Ministry of Women and Child Development) have prepared their own calculations based on UNDP calculation methods, with partly divergent values. They serve as planning bases for improvement programmes; the respective ranking may refer to the 29 states ofIndia or also include the 7 Union Territories. The HDI of the total 705 Scheduled Tribes is calculated as a low 0.270 (unchanged since 2000).

- 1991: HDI of Meghalaya ranked 18th with 0.464 (India: 0.432)

According to Meghalaya's government:' ranked 24th with 0.365 (India: 0.381), and the then

GDI Gender Disparity Index: ranked '7 at 0.807 (India: 0.676).

Both governments cite the matrilineality of society ("due to matrilineal society") as the reason for this gender advantage compared to the India-wide average.

- 2006: HDI of Meghalaya ranked 22nd with 0.543 (India: 0.544)

The Union Government states: rank 17 with 0.629 (India: 0.605), and the

GDI Gender Development Index: rank 14 with 0.624 (India: 0.590), and the

GEM Gender Empowerment Measure: ranked 28th at 0.346 (India: 0.497).

UNDP's GII Gender Inequality Index in 2011 for all India: 0.617 ranked 129th (out of 146 countries).

- 2017: HDI of Meghalaya ranked 19th at 0.650 = comparable to Guatemala or Tajikistan (also compare Meghalaya in India-wide list by GDP).

HDI of all Scheduled Tribes still only 0.270

India ranks 130th in the world with 0.640 (2016: 129th), comparable to Namibia, in the group of countries with "medium human development"

GDI Gender Development Index: ranked 149th at 0.841 (HDI 0.575 ♀ to 0.683 ♂).

GII Gender Inequality Index ranked 127th with 0.524

In terms of gender, the large Indian state with its population of more than 1.3 billion has low scores, mainly due to low female employment and political participation (GDI and GII are not known for Meghalaya).

Femdex (2015)

The index called Femdex (Female Empowerment Index: comparable to the former GEM) was calculated by the McKinsey Global Institute in 2015 for the 28 Indian states and the 3 largest of the Union Territories. Here, Meghalaya ranked 2nd at 0.69 (behind Mizoram at 0.70; India: 0.54), comparable to Argentina, China and Indonesia - while neighbouring Assam had the third lowest Femdex in India at 0.47 (comparable to Yemen or Chad). Gender equality in terms of work was much more pronounced in Meghalaya and Mizoram at 0.56 than in the other states, with women in Mizoram being socially better off at 0.87 than in Meghalaya at 0.82 (ranked 1: Chandigarh at 0.92).

2011: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) 2011f per capita in India (world list) 2011f Meghalaya low 2014: Meghalaya ranked 20

2006 with values of the Union Government: HDI India: ' 0.605Meghalaya : 0.629 (see map) 2006 - United Nations values: HDI India:f 0.544Meghalaya : 0.543 (UNDP HDI list)

2011: Reading ability in India: 73.0 %. Meghalaya | Women | Men | Cardalle : ' 74.4 % 72.9 % 76.0 % Khasi: 77.0 % 78.5 % 75.5 % Garo: 71.8 % 67.6 % 76.0 % Meghalaya | Women | Men2001 : 62.6 % 59.6 % 65.4 %1991 : 49.1 % 44.9 % 53.1 %1981: 43.2 % 38.3 % 47.8 %1971: 35.1 % 29.3 % 40.4 %1961: 32.0 % 25.3 % 38.1 %1951: 15.8 % 11.2 % 20.2 %

2011: Sex distribution in IndiaNumber of male babies up to 1 year of age in relation to 100 femaleMeghalaya : ≈ 104 ♂ to 100 ♀.

Street vendor of paan: finely chopped betel nuts and spices wrapped with leaves of betel pepper and coated with slaked lime; legal selling and daily chewing of the mildly narcotic stimulant drug is widespread in India, it reddens gums and blackens teeth (Shillong, Meghalaya, 2014)

Former slash-and-burn agriculture in today's small UNESCO biosphere reserve Nokrek in the Garo Mountains (2004)

2011: Shares of the 705 Scheduled Tribes in the populations of the 29 states and 7 Union Territories in India. highest percentage: 85-95 low percentage: 2-9 % 08.6 % of the total population86 .1 % of the inhabitants of Meghalaya 55.2 % are Khasi (48 % of the inhabitants) 32.1 % are Garo (28 % of the inhabitants)

The Khasi people consist of several tribes and sub-tribes, listed in the 2011 census as "Khasi, Jaintia, Synteng, Pnar, War, Bhoi, Lyngngam" (1,412,000 in the state of Meghalaya, 48% of the total population). Each tribe is composed of independent clans, each clan consists of many extended families who consider themselves related to each other. These clans form over 60 chiefdoms in Khasi and Jaintia territory (see below for political structures).

Matrilineal extended families ("houses")

The smallest independent social and economic unit of the Khasi is the 3-generation family, called iing (house, family), respectfully and affectionately referred to as shi iing "One House": a woman with her children and the children of her daughters, i.e. the extended family of a grandmother with grandchildren. All members of the iing live together or close to each other in the village community, including the (unmarried) sons and grandsons. This family is headed by the grandmother, in consultation with all adult relatives (cooperative). Often a brother or uncle of the grandmother lives with her, sometimes a sister or aunt, gladly with offspring.

The following diagram shows an example of an iing, founded by the "mother", the kinship names are related to her (grandmother from the point of view of her grandchildren):

|

|

|

|

| Progenitor mother |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother's brother |

| "Mother" |

|

|

| Mother's Sister |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sons |

| Heir daughter |

|

| Daughter |

| Daughter |

|

| Nephews (cousins) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| grandsons |

| Granddaughter |

| Granddaughters |

|

| Granddaughters |

| Grandson |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| great-grandchild |

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Land ownership: The house and land ownership, the rights of use and the assets of an extended family are exclusively in the expert hands of the "mother", usually managed by her older brother ("mother-brother") or her uncle (her social father), in consultation with all adult members of the iing in the manner of a cooperative or cooperative as a community of solidarity. The "mother" started her iing with her own kitchen garden and dwelling house as well as land use rights, to which her descendants have added or earned additional land and use rights within the village community (see above on village land administration). Her youngest daughter will inherit all of this and in turn pass it on to her youngest daughter (see below on succession by youngest daughters). If a woman has no daughter, she cannot establish iing because the family would not continue; the woman remains (perhaps with sons) with her mother or joins a sister and her children to support her.

| Data |

|

A Khasi woman asks questions at a briefing on measures under the Bharat Nirman, the government's rural development programme (Tynring, Eastern Khasi Hills, Meghalaya, 2013) |

| Matrilinearity |

| Northeast India:' Khasi, Garo Linearity of all 1267 ethnic groups worldwide:(1998)

1300 ethnic groups are recorded worldwide (2018). |

| Matrilocality |

| 164 matrilineal ethnic groups worldwide - their marital residence after marriage:

neo-local = in a new place bi-local = in both places (mother/father) ambi-local = selectable: with mother or father nato-local = at the respective place of birth = "visiting marriage": man only comes overnight 1 patri-lineal ethnicity of 584 resides matri-locally. |

| Matrifocality |

| Matrifocality = "matrifocused, matricentered" "Matriarchy" = latin. "rule of the mother" ↔' feminist: "in the beginning the mothers". History of matriarchal theories =1861 |

| Matriarchy? |

- Identical descent: All the relatives shown are related to each other by blood, all are descendants of the same woman: the mother of the "mother" (from the grandchildren's point of view: the great-grandmother). In their understanding of consanguinity, the biological fathers of the relatives play no role; they do not belong to the iing. This extended family also does not include children of brothers, sons or grandsons - like the biological fathers, all children of the male relatives belong to the extended families of their own mothers. Thus, the family shown is not a whole extended family, but a half extended family (only 1 of the 2 parental lineages): sons of all generations inherit the family and clan name from their mother, but cannot in turn inherit it, and sons cannot inherit landed property, title, or privilege from their mother (nor from their father).

This restriction to matrilineal

descent is technically called matrilineality: "in the line of the mother," and is found in some 160 ethnic groups and indigenous peoples worldwide. Such a matrilineal lineage goes further back through the physical foremothers to a progenitor mother (sometimes only legendary) who is revered as the founder of the entire lineage (see below). In contrast to this are families of other peoples who derive their descent only from the father and his forefathers (patrilinearity: "in the line of the father"); in some peoples children inherit certain affiliations and positions only from the mother's side of the line, others only from the father's side (bilinearity, example: Jewish religion from the mother - Jewish ethnicity through the father). The

Khasi also know forms of joint adoption: After the adoption of an unrelated person "in the place of a child", this person becomes a member of the adopting mother's family and receives her clan affiliation.

- Social fathers: All brothers care for the children and children's children of their sisters, in all generations (see below on the importance of mother brothers and their social fatherhood).

- Husbands: "Married-in" husbands may live with the wives of the iing, as supporters of the whole family - but they are not members of the "house", for they are sons of other iing to whom they belong. The married men of the family (brothers, sons, grandsons) are absent, residing in the families of their wives, as married-in supporters; that is where their natural children belong (see below on residence with the mother). Since all husbands are also social fathers to their own sister children, a husband's biological children always have a social father as well, often several (see below on men's family roles).

Advantages of the matri-linear extended family:

- The "mother" first provided for her children and does the same for her daughters' children (the daughters' eggs have already been created in the "mother's" womb). With the accumulated economic wealth of the family, the "mother" now ensures the raising of her grandchildren and can care for them. This support of a mother by her mother is seen as a human evolutionary advantage, because it measurably improves the survival possibilities of the grandchildren - in comparison to other primate species and also to patrilineally ordered families, in which the wives basically live separately from their mothers and often have to subordinate themselves to the husband's mother (compare findings on the importance of the maternal grandmother).

- The power of disposal over the economic assets in the hands of only one group mother guarantees the security of all dependents, including those who are not able to work: Children, the sick, the disabled, the handicapped and the elderly of several generations. Thus all men and women are covered as members of their mother's or sister's family. All of their interest in this social security acts as a check on the group mother and her advising brother or uncle not to jeopardize the group's fortune by way of wayward decisions or interests. The Khasi extended family sees itself as a solidarity community in the manner of a "social insurance", to which all members "pay in" their available labour and income.

Matrilineal Lineages ("Bellies")

At the latest with the birth of the "great-grandchild" indicated in the diagram, its grandmother (the "older daughter") is thinking about moving out. With her husband, a brother or uncle as well as her children and the husbands of her daughters she now is going to found her own iing, a new "house" (compare also nobility/ruler "house" and differences "house, family, family sex"). Then the "mother" has "produced" from her bodily womb a new, independent extended family: a grandmother with granddaughters. She is now a great-grandmother, probably over 50 years old, and has successfully managed her family business as an experienced family manager - in close cooperation with the many other family branches of her lineage as well as the other clan families in her village community.

With the departure of the "elder daughter" the remaining extended family has grown to the next largest social unit of the Khasi, to a self-confident kpoh, literally "belly, womb", technically lineage: a "single-line descent group" with at least 4 living generations, with the Khasi going back after the line of their mother, her mother, and so on (maternal line). Worldwide, individual families live with 6 generations, the Guinness Book names 7 as a world record: a line through 6 generations of women from the 109-year-old great-great-great-grandmother Augusta Bunge to her newborn biological great-great-great-grandson in 1989 in the USA (compare generation names). The chart of a living Khasi great-great-great grandmother would depict over 200 members of her 6 successor generations.

This lineage, respectfully referred to as shi kpoh "One Belly" (One Womb, One, United), will be continued by the heir daughter and then her youngest daughter, forming new iings with each "elder daughter" in each generation. The extended family of the outgoing elder daughter will in turn grow into a kpoh a generation later, a lineage of its own (also called a "subclan"). Khasi women are generally not considered inferior if they have no children, or only sons, or if they do not feel called to set up their own house - in a sisterly household their support is welcome and they are offered security.

The designation of such large family groups as "clan" is inaccurate and outdated, it refers to the ancient Germanic tribes; likewise reserved for the patri-linear extended families is the designation as "lineage" (succession after the "male tribe"). The designation of a lineage as a "clan" is also incorrect, because such a clan is understood as a superordinate association of many individual lineages that derive their commonality from descent, from a local origin or from other identity-forming references (compare also totemic clans).

Ancestor Worship

The original founder of a kpoh is revered as "the Old Grandmother": ka Lawbei-Tymmen. This ancestral mother is asked for protection against suspected external evil influences on the whole family with ceremonies and offerings. The veneration of ancestors, technically called ancestor worship, is a natural part of the Khasi world view: The remembered powers of the foundress reach into the present and are often invoked to ward off unwanted forces from the surrounding nature or from other persons. For her part, the kpoh foundress is considered a blood descendant of the original "fundamental Great Mother" of the entire lineage, the ka Lawbei-Tynrai (lawbei: great mother; tynrai: fundamental; see above for chanted names). Over the course of centuries, hundreds of lineages related by blood to one another may have outgrown the "womb" (kpoh) of the ancestress-she is held in honorable memory by all her descendants. This presence of the common ancestor causes all these descendants to feel "sistered" to each other and share a solidarity that distinguishes them from the descendants of the other Khasi ancestresses (compare culture of remembrance). They see themselves as members of a large family and form a "clan", in the manner of an interest group, with all the belonging kpoh as "subclans".

In addition to the respective kpoh progenitor mother, her (then) husband is also honoured and asked for assistance: u Thawlang, as "the First Father", can provide spiritual help, especially in disputes within the family. Even more, the eldest brother of the ancestral mother is revered as u Suid-Nia: "the First Uncle" (on the mother's side). He is often found as the largest of the three upright memorial stones (mawbynna), some of which can be several meters high (comparable to megaliths). The upright stones represent the male ancestors protecting their reclining sisters and nieces. They are not graves, but honorary tombs visible from afar, comparable to the old European menhirs (see pictures).

Residence with the mother

Khasi follow their traditional marriage rules, which forbid marriage within one's own clan and can punish it with the couple's final expulsion (see below on the religious incest taboo). This universal rule of exogamy (external marriage) first prevents incest, since all descent groups within a clan (kpoh, iing) are related to each other by blood through branching maternal lines - or are at least considered to be related by blood. Going further, exogamous marriage rules serve the need for hereditary mixing through systematic avoidance of similar hereditary material within one's own clan. In addition, inter-clan marriages often serve the social fraternization or political alliance of clans (alliance building). Worldwide, most clans only marry members of other clans, and some have formed solely for this reason. Marriage partners have to be sought in the extended families of other Khasi clans, among them can also be the children of the mother's brother or mother's uncle, because these cousins do not belong to their own clan but to the clans of their mothers (compare the ethnological technical term of cross-cousin marriage). Before a planned marriage, the mothers of the bride and groom will carefully check whether the two did not have a common ancestor in the distant past. This rule of exogamy is restricted by endogamous rules and prohibitions to the contrary (internal marriage): Thus, it is considered desirable to marry within the Khasi village community; non-Khasi as spouses are not desired in many clans, and in recent times men have even threatened to punish them (see below). In the border areas there is sometimes a tolerated exchange of marriage partners with neighbouring indigenous people (see below).

In the middle of the last century, Khasi women mostly married between the ages of 13 and 18 and men between 18 and 35; there is now a legal minimum age of 18 for women and 21 for men. In 2001, the census revealed regarding marriages among Khasi (with Jaintia) and the small group of Synteng (1,300 dependents):

- 63.4 % unmarried (highest rate among Scheduled Tribes in Meghalaya)

- 30.9 % married (lowest rate of the tribes)

- 03.2 % widowed

- 02.5 % divorced/separated (highest rate of the Tribes)

- 01.4% of girls under 18 had married (lowest rate among the Tribes; highest: 1.8% among the Synteng)

- 01.3% of males under 21 had married (1.5% for synteng: highest rate)

In order to choose a husband, a woman must either provide social security through her mother's family's property as an heiress daughter, or the opportunity to be promoted through her mother's family as an "older daughter." The youngest daughter will never move out of her mother's house, the prospective husband must move in with her; older daughters have more freedom and can establish a new residence with her husband over time, near the mother's house.

In general, the desire for contact comes from the women, and the local weekly markets also serve as a marriage market. The young men like to come here, or they proudly present themselves to the assembled ladies at the monthly feasts and festivals of the Khasi calendar. At wedding ceremonies, ritual gifts are exchanged between the two families, such as the universally prized betel nuts and betel leaves. There are no bride-price payments or a morning gift on the part of the husband among the Khasi, nor is there the dowry system of the dowry, which is widespread throughout India and in which husbands demand high dowries from the bride's parents (compare dowry murder). The clan of the spouse is respectfully referred to as kha (comparable to a sister-in-law), while one's own clan is affectionately called kur. According to both Khasi tradition and their Christianization, the Khasi conduct marital relations monogamously ("one marriage"). Divorce was traditionally quite easy and could well be initiated by the woman; even today the Khasi divorce rate is slightly above the Indian average. "Single" Khasi mothers and related problems are almost non-existent, as at least female family members live in the house, plus the importance of the older brother or uncle for the mother and her child.

The chosen husband has hitherto supported and worked for his own maternal family - now the wife expects him to move in with her and her extended family and support them and the planned children. This choice of marital residence is technically called matrilocality: "at the place of the mother". In an analysis of all 1300 or so data sets on ethnic groups and indigenous peoples worldwide, matrilocality is found in one-third of the 160 or so matrilineal cultures, and even more prefer avunculocality: marital residence with the wife's mother's brother (her maternal uncle). In the case of a wife who is not entitled to inherit, in more recent times residence "in a new place" (neolocality) is also increasingly being considered, with employment opportunities in cities playing a role in particular.

Since a wife is normally secured by her mother's family, she is not necessarily dependent on the presence and assistance of her husband, in some cases the latter stays predominantly with his own extended family, both spouses remain respectively "at the place of their birth" (natolocal). Already earlier ethnologists reported observations among the Khasi tribe of the Jaintia (Synteng/Pnar) that the husband remained at his mother's place of residence and visited his wife only occasionally, mainly overnight. In 1952, the German priest and ethnologist Wilhelm Schmidt put forward the thesis of a "visiting marriage" as an "even older form of maternal law" (compare also the small southern Chinese people of the Mosuo). In fact, Khasi husbands often do not contribute all their labour to the wife's household or (temporarily) leave their partner again; this is compensated by the unmarried male members of the extended family living with them as well as by the support of the wife's mother (grandmother of the children).

After a birth, therefore, a Khasi mother is assisted in her extended family not only by her mother and other experienced relatives, but also by her social father (uncle), her favourite brother, and - if desired (and known) - the biological father of the child.

Succession of the youngest daughter (Ultimagenitur)

To this day, almost all Khasi adhere to their traditional way of life within a matri-lineal and matri-local social order (technically matrifocality: "matri-centred, matri-focused"), in which the mother's lineage, choice of residence and succession prevail: the children are attributed to the mother and goods, rights, privileges and duties are inherited from the mothers to their daughters, preferably to the youngest. Male descendants within an extended family also receive the family and clan name, are attributed to the whole lineage, and reside in their mother's place (as long as unmarried); in advanced age, they like to live with a sister and her children. But they cannot pass on this membership to their biological children, because they are descended from the mother, not from them (compare descent rules). Therefore, men do not inherit property from their mother; it would be taken from the family property without providing any benefit to the extended family. Among the Jaintia tribe, a man's (mother's) clan can even claim his private property as clan property. A Khasi man, therefore, cannot bequeath anything to his children except personal property, for the inherited property would change from his mother's side clan to his children's mother's clan. Such a change of property and land is impossible between clans and is only possible by mutual exchange by mutual consent (in earlier times occasionally by war).

The lands and buildings belong to the group mother, managed mostly by her brother or her social father (uncle). The earnings from work, agriculture, production and trade of the family members also go to the mother. In earlier times, the Khasi did not know any distinct private property apart from their personal ornaments; even today, the land ownership of an extended family is mostly managed in the manner of a cooperativeorcooperative (see above on the extended family as social security).

Ultimagenitur

The youngest daughter of a Khasi mother has an official title: ka Khadduh ("the custodian" of the ancestral property), conferred by the mother if she does not want another child. According to tradition, the last-born is intended to be the mother's principal heir and will inherit the family home and land (compare heiress daughter). She will cherish her mother's jewelry, which may have been accumulated for generations. Older sisters expect a small share of the inheritance, especially if they are about to establish their own "house" (iing). Sons rarely get an inheritance share, perhaps some movable property such as animals, but no land. Among the War-Khasi tribe (in the southern border area), inheritance is divided equally between daughters and sons.

The succession to the youngest child is technically called ultimogeniture (last-born right), in the case of the youngest daughter ultimageniture ("the last-born as successor") - in double contrast to primogeniture as the inheritance right of the first-born son in patrilineal families. In some Khasi areas, the youngest daughter gets the best schooling from the start; generally, schooling is encouraged, but females have a 3% higher literacy rate than males (see above for literacy rate). In contrast to the Khasi, among the matrilineal Garo people, who are neighbors to the west, the eldest daughter inherits preferentially (the firstborn as the daughter of inheritance: primageniture). Among them, the position of village head (nokmas) is assumed only by a youngest daughter.

The following chart shows the succession of the youngest daughter:

|

|

|

|

| "Mother." |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Sons |

| youngest = |

| olderdaughter |

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| grandsons |

| (youngest) |

| (youngest) |

| grandsons |

| |||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

After the death of the "mother", her youngest daughter inherits most or all of the economic assets and family land and becomes the new head of the extended family (iing) or the larger lineage (kpoh). She may well already be a grandmother herself. She also inherits the ka Bat ka Niam, the religious, spiritual responsibility for the extended family (see below on the Niam Khasi religion), as well as the ka Iing-Seng, the ceremonial house of the group (iing: house, family; seng: united). In this, the understanding of the united Khasi extended family as a managed cooperative requires the heiress to be in constant consultation with all adult family members, including the more experienced and the respected elders. She will in turn pass on the leadership and overall ownership to her youngest daughter; this is the form in which the lineages have held their land together for many centuries, while always supporting the newly emerging branches of the family with a dwelling house and a small field area. The youngest daughter of an "elder daughter" also inherits her property and jewels, if already accumulated; in any case, she inherits responsibility for her siblings and her sisters' children (her nieces and nephews).

If the intended heir's daughter proves to be too young or unsuitable or is not accepted by the family council, an older daughter or a daughter of the mother's sister can take her place: In the case of the choice of a sister's daughter (cousin of the heir's daughter), this would also continue the straight line of the "mother", only no longer through the youngest lateral line (compare straight line versus lateral relationship, always relative: all children and children's children of a woman continue her straight line, all children are lateral lines to each other).

Reasons for the Ultimagenitur scheme and its benefits for the extended family:

- Preferring only one child (as sole heir) keeps the accumulated property of the whole family together - if several children inherit a separate share, the economic fortune and the social security and effective possibility of all relatives is weakened.

- A daughter is what all Khasi want - not so much to continue the line or for inheritance reasons, but to take care of them in their old age.

- The youngest daughter ensures longer care and provision for her mother in old age - traditionally the youngest often receives preferential schooling and takes on the role of the mother's personal assistant and apprentice at an early age in preparation for her managerial duties (training to become a family manager); all family members live in the knowledge that the sole heir is prepared and will care for the parents.

- The youngest usually outlives her older sisters - the passing of overall responsibility from one generation to the next changes less frequently.

- The heiress cannot claim any additional authority as the eldest or most experienced of the children - she must consult with all adult family members (consensus principle), and she also has her experienced social father (uncle: mother's brother) and usually an older brother at her side.

If a mother has another daughter after the "hereditary daughter", this daughter will take over. A mother's ability to conceive is limited in time, her natural menopause can begin from the age of 45 (average: from the age of 51; compare also the grandmother hypothesis). In contrast, fathers can still father many children in old age, which in patri-lineal families often results in problems concerning illegitimacy (legitimacy), neglect or even neglect of such children - among the Khasi there are hardly any problems in this respect.

Conflicts:

- From the beginning, the heiress daughter is prepared for her role - but also forced into responsibility. For a girl of the present time, this requires a far-reaching assessment of her situation, because as an heiress daughter she can never leave her beloved shi iing. It is true that she offers her future husband a "good match" with social security, but her future husband would have to subordinate himself entirely to her perspective on life - another place of residence would be out of the question, not without the "mother" (and her husband). But not all men are ready for this, many prefer to move in with an "older daughter", and preferably outside her mother's home. The prevailing estimate cites no conspicuousness or social friction, for the obligations of the particular expectation are never too strictly framed, and leave scope for their execution. If the intended heir's daughter does not make it or does not want to take on the responsibility, there are obvious alternatives: Her sister or a cousin (daughter of the mother's sister) may agree to stay with the mother for the rest of her life and take over family management from her. In addition, sisters and brothers as well as uncles and aunts are happy to help because the community is important to them.

Matrilineal clans

Each Khasi clan sees itself as an interest group of interrelated kpoh (bellies) and iing (houses) and derives all of its ancestry from a common ancestor, an original progenitor mother who may have lived many generations and centuries ago. This is respectfully called "The Great Mother of the Root" (of the clan tree): ka Lawbei-Tynrai (lawbei: great mother; tynrai: fundamental). Not all clans can name their foundress and the generations of mothers following her, they then speak generalizingly of their "Fundamental Grandmothers", to whom highest reverence is due. Again and again, on special occasions, individual groups or small tribes had joined other Khasi clans and then embellished a common origin (an "Ansippung" with fictitious genealogy). For all clans, it is taken for granted that none of these many founders were related to each other. Some clans, however, derive from different daughters of a "founding grandmother", see themselves as an independent clan line in each case and often form a clan association together. Thus, over time, individual family branches have in turn become independent clans of their own, and perhaps foreign groups have joined in between: The names of matrilineal clans collected by one Khasi researcher amounted to 3363, combined into clan associations and chiefdoms. In contrast, the 1 million members of the neighbouring matrilineal Garo are divided into only three large clans (katchis).

Clan Mother

A Khasi clan is led by a clan mother (compare "clan mother" among Indians), usually one of the oldest and most experienced women of the large family unit - while the clan chief, who is co-determined by her, performs administrative, representative and political tasks outside. Clan mothers and chiefs are bound by decisions of the clan council (dorbar) or clan assemblies and can be voted out if necessary. Like other indigenouspeoples, the Khasi know a strict division of labour according to gender (gender order) in many areas, which can hardly be broken by individuals: women are responsible for their activities, men for theirs. Both areas are coordinated by mutual agreement. An example of the responsibilities is told by a legend from the Jaintia tribe, according to which the clan mother - as spiritual leader also the high priestess - managed the entire assets of the chiefdom and was reluctant to give her chief sparse financial resources.

Mixed lines

In border areas or on occasion, entire families may be "adopted" by a lineage or its clan, with appropriate adoption rituals. Individual Khasi subgroups handle the importance of male lineage differently and involve both sexes in inheritances. Among the northeastern Khasi tribe of Bhoi (in the Ri-Bhoi district), matrilineal lineages can be carried on staggered over two generations: There, a woman without a daughter will ask her son to marry a woman of the neighboring Karbi people. The small ethnic group of the Karbi, also called Mikir, settles in the adjacent Assamese district of Karbi Anglong and consists of patri-lineal clans (patrilines). The children of such a mixed marriage belong to the patrilineal Karbi clan of the wife, because the Khasi father cannot pass on his matrilineal group affiliation to his children. His youngest granddaughter, however, reassumes the name of her Khasi great-grandmother and continues her lineage matrilineally; thus she changes her clan affiliation (within her village community) and switches from the Karbi back to the Khasi people. Such mixtures and alliances between opposing clan lineages exist in various borderlands, in some clans or tribes some members feel they belong to a different tribe or clan - depending on the lineage they prefer. There are entire clan groups that refer to themselves as Garo-Khasi, while others try to distinguish themselves as their own sub-tribe from other Khasi tribes (see below on the "Seven Lodges").

Fundamental to the tribal diversity is the unity and community of one's own clan (kur) and the pride of belonging to it. Accordingly, among the Khasi the male leaders do not lead a tribe but their clan, elected chief by their clan council and the clan mother. In a federation of clans, the largest clan provides the common chief; he works together with the other leaders and clan mothers, but presides over them in a representative capacity and also represents the whole community externally.

Roles of the men

Like almost all of the approximately 160 matrilineal ethnic groups worldwide, the Khasi also follow a traditional division of labour between the sexes (compare difference: gender habitus vs. gender role, gender order). Khasi men are of equal importance to their female tribesmen: They have basic tasks within their nuclear family, extended family (iing) and lineage (kpoh), but in addition they have tasks in external representation, including representative and religious ones, which are less often or hardly ever performed by women. While the female principle is revered in the idea of the strong goddess who is supported by a husband, the British colonial rulers tried for 150 years to restrict the role model for landowning women to the family and domestic sphere. This pressure is also perpetuated within the Khasi organisations by a growing male self-esteem, which can increasingly take on masculinist forms, accompanied by the formation of nationalist and populist opinions.

The following list describes the social roles that arise for Khasi men through kinship, marriage and politics:

- Sons are just as welcome as daughters (see above on sex ratio), though Khasi want at least one daughter to care for in old age. Sons get the family and the clan name from their mother as an expression of the group affiliation also to the superior clan, but according to Khasi tradition they cannot inherit any rights, titles or privileges from their mother, especially no land or house ownership. From the father, sons inherit nothing, for he cannot inherit his group membership and usually owns no land or property of his own. A son provides much of his mother's support, and later that of his wife and her mother.

- Brothers are very important for sisters: a brother will protect and support his sister, perhaps also live with her and her husband, but above all he will assume social fatherhood for her children (his nieces and nephews), the sister children will also call him father. The eldest brother will become the guiding and protective uncle of the family.

- Uncles (kñi, mother brothers), in addition to their social paternity, have the task of managing their family's land and household property: They are the experienced advisors of their sisters and nieces and may assume duties as male head of their extended family or lineage (see above on uncle worship). As such, father-side uncles (father-brothers) have no special role, nor do father-side aunts (father-sisters). In contrast, the mother-side aunts (mother-sisters) belong to the closely trusted family members.

- Cousins are distinguished according to which parental side they are cousins: The sons of maternal sisters belong to the family, are equal to brothers of their own. The sons of father's sisters belong to another clan, are not seen as blood relatives and can be married (compare cross-cousin marriage).

- Husbands are always welcome in women's families; they are considered the head of their nuclear family, contribute to the upkeep of the wife's extended family, and help maintain and manage their family property. A husband lives with wife close to or in her extended family, but also continues to take care of his own sister's children. It may happen that both spouses stay with their mother families by mutual agreement (compare visiting marriage: husband visits his wife only overnight). With other children of his wife (his stepchildren) he has a relaxed relationship: he will accept the role of their social father without weighing up which child he might prefer for reasons of inheritance. As long as a husband lives with his wife, he cannot claim land use rights with his family of origin, he farms the land of his wife and her family or goes to work for them.

- Fathers are seen as belonging to another clan (see clan-internal marriage ban), whose lineage is honored but not continued by his children, because they belong only to their mother's clan. While the mother's clan is affectionately called kur, the father's clan is respectfully called kha, expressing a kind of relationship of sisterhood. The Khasi maxim "Know your kur, know your kha" (tip kur tip kha) expresses the connection of both clan lineages. A father cannot bequeath anything, but knows that his children are in good hands with their mother; in his own clan, as a brother, he assumes the protection of his sister, and as an uncle, he assumes social paternity for her children.

- Grandfathers do not play a special role: The father of the father has little relation to his children's children - he lives with his own family and is important there as a great uncle for the children and children's children of his sister. The mother's father, as the husband of the grandmother, probably lives with the extended family, but is also the social father of his own sister's children.

- The head of the family (jaid) is a man: in the nuclear family the husband (if he lives with the wife) or the uncle or elder brother of the wife, in the extended family the husband of the grandmother in interaction with her brother and uncle. The head of the family has mainly official duties at religious ceremonies. Christianization has preached to the Khasi for two centuries the notion of the father as the "head of the family," while the Khasi tradition sees the wife's uncle (u kñi), her social father, as the "head" and protector.

- The village head-man is appointed by the village council, comparable to an official mayor, usually a man. The Indian system of village panchayat self-government also favours men for this political task and uses only male designations (see below on village politics).

- The chief of a clan (chief) is appointed by the clan council (dorbar) and the clan mother (often her nephew) - only in rare cases does a woman take on this political task of external representation and coordination with other villages and chiefs. Already in the British colonial period the importance of the clan chiefs was increased compared to the clan mothers (see below).

The weighting of the individual roles and the way they are shaped can differ among the various Khasi groups and tribes - the basic principle remains the interplay between the husband and the wife's uncle (her social father) and the wife's older brother (her protector and social father of her children): if one of them does not live with the wife, then one of the others; children have a "father" at their side in any case.

Mother brother (social father)

Although many Khasi men move in with the wife after marriage (matrilocal), where they have to contribute their work and earnings, after the birth of a joint child the (older) brother of the wife will also establish a close relationship with the child, who will also call him father. Khasi men basically take care of their sister children (their nephews and nieces) and assume social fatherhood for them from the very beginning (compare Social Parenthood). This importance of the mother-brother is found in most of the approximately 160 matrilineal ethnic groups worldwide. For comparison: In the German language there is also the old term "Oheim" for the maternal uncle, who had a special meaning as the caretaker of his sister's children (compare also Patenonkel). In Latin, the mother's brother is called avunculus, from which is derived technically the avunculate for the social paternity of the mother's uncle. Together with avunculocality (matrimonial residence with the mother's brother), avunculate can be understood as kin selection: the promotion of sister children as proportional carriers of one's own genetic material (kinship coefficient: 25%) to strengthen overall biological fitness. A further socio-cultural evolutionary advantage comes from the fact that Khasi children can have several "fathers" at their side as protectors and supporters.

Classification

The exclusion of Khasi men from the inheritance of the land and buildings of their mother families guarantees that the ownership of the economic foundations remains in the hands of the women, more precisely: the (grand)mothers. However, these are not given the hand to manage for their own purposes and out of personal interest - the mothers manage the land and houses as social security for the entire extended family. Thus all men (as sons and brothers) are secured through the families of their mothers, for which purpose they contribute their work and earnings there (see above on social security on the mother's side). Mothers additionally secure the children of their daughters - but not the children of their sons, because these are not counted as part of the family, but belong to the family and clan of the respective mother and her mother. For a Khasi man as a father, the result is that his biological children are socially and economically secured in the family of the (wife), under his demanded assistance; in addition, his children have a social "father" there, their uncle. A husband always has to fulfill his family duties as well and to protect and promote the children of his sister, for whom he is the social father as uncle.

This dual father role results in a fundamental contradiction for men in matrilineal societies between their paternal feelings for their biological children and their responsibility for their sister's (blood-related) children. This constellation has been termed the "matrilineal puzzle" in research conducted in the "matrilineal belt" of the Congo region of Africa: The sister's children continue the husband's line, while his biological descendants continue their mother's line. The mother, in turn, has to deal with the influence of her brother, who exercises a kind of guardianship over her children.

Conflicts

The labour and earnings of a Khasi man belong to his mother before marriage - after marriage to his wife and her mother. In recent decades this clear division is changing, and in inheritances the older daughters and the sons also want a greater share. Increasingly, men are claiming their own rights in terms of marital residence, as well as the parentage of their children and the transmission of their own family name. As wage labourers, craftsmen, traders or businessmen, men want to dispose of their own earnings and accumulate their own property, including land (see above on the conflicts caused by land privatisation and population explosion). In addition, there is widespread rural exodus (urbanization) as men and young married couples increasingly move to larger cities and conform to Western lifestyles. In 2011, 22% of Khasi lived in urban environments (national average: 20%) and there were 1.6% more women than men (23,000) among the 1.4 million Khasi in the state of Meghalaya. The Khasi have for decades resisted the increasing immigration of single men from Hindu West Bengal and Muslim Bangladesh, which borders them to the south. Since the state was founded in 1972, there have been repeated protests with violent attacks against "foreigners", especially in the capital Shillong, where even generations-old West Bengalis, Nepalese and others have been targeted as "non-tribal". The biggest riots took place in 1987, 1992 and 2013.