Karate

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Karate (disambiguation).

Karate [kaɺate] ![]() (Japanese 空手, engl. "empty hand") is a martial art whose history can be safely traced back to 19th century Okinawa. It is a martial art whose history can be traced back to 19th-century Okinawa, where native Okinawan traditions (okinawa Ti, 手) merged with Chinese influences (jap. Shorin Kempō / Kenpō; chin. Shàolín Quánfǎ) to form the historical Tode (okin. Tōdi, 唐手). At the beginning of the 20th century, this found its way to Japan and was spread from there across the world as karate after the Second World War.

(Japanese 空手, engl. "empty hand") is a martial art whose history can be safely traced back to 19th century Okinawa. It is a martial art whose history can be traced back to 19th-century Okinawa, where native Okinawan traditions (okinawa Ti, 手) merged with Chinese influences (jap. Shorin Kempō / Kenpō; chin. Shàolín Quánfǎ) to form the historical Tode (okin. Tōdi, 唐手). At the beginning of the 20th century, this found its way to Japan and was spread from there across the world as karate after the Second World War.

In terms of content, karate is mainly characterized by punching, pushing, kicking and blocking techniques as well as foot sweeping techniques as the core of the training. A few levers and throws are also taught (after sufficient mastery of the basic techniques), in advanced training also choke holds and nerve point techniques are practiced. Sometimes the application of techniques with the aid of Kobudō weapons is practiced, although weapons training is not an integral part of karate.

Quite a high value is usually placed on the physical condition, which nowadays has in particular mobility, speed strength and anaerobic resilience as its goal. The hardening of the limbs, among other things, with the goal of the breaking test (jap. Tameshiwari, 試し割り), so the smashing of boards or bricks, is less popular today, but is still practiced by individual styles (for example: Okinawan Goju Ryu).

Modern karate training is often more sports-oriented. This means that great importance is attached to competition. This orientation is often criticized because it is believed that this limits the teaching of effective self-defense techniques, which are definitely part of karate, and dilutes karate.

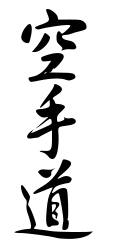

Calligraphy of Japanese Kanji characters for "Karatedō"

History

Name

Karate-"dō" (jap. 空手道 'way of the empty hand') used to be referred to mostly just as karate and is still most commonly referred to under this name. The suffix "dō" is used to emphasize the philosophical background of the art and its importance as a way of life. Until the 1930s, the spelling "唐手" was common, literally meaning "Chinese hand" or "foreign hand". The character "唐" with the Sino-Japanese reading tō and the Japanese reading kara referred to Tang Dynasty China (618 to 907 AD). Thus, the Chinese origins were already manifested in the name of the martial art. Probably for political reasons - Japanese nationalism - at the beginning of the 20th century, initialized by Funakoshi Gichin, people in Japan switched to using the homophonic spelling kara "空", meaning "empty, void". The historical "Chinese hand" or "foreign hand" (karate, 唐手) became the current "karate" (空手) with the meaning for "empty hand". The new character was read like the old kara and was also appropriate in meaning in that karate usually involves fighting with empty hands, i.e. without weapons. (cf. Tang Soo Do)

In German, in the pronunciation of the word "karate", an emphasis on the second syllable is common. Often, even as in several Romance languages, for example, in French or Portuguese, emphasis is placed on "te"; in Spanish, however, on the first syllable "Ká". According to the Japanese pronunciation of the word, on the other hand, an equal accentuation of each syllable is common.

Origins

Die Legende erzählt, dass der buddhistische Mönch Daruma Taishi (jap. 達磨大師, dt. Meister Bodhidharma, in chinesischen Chroniken als „blauäugiger Mönch“ bekannt) aus Persien oder Kanchipuram (Südindien) im 6. Jahrhundert das Kloster Shaolin (jap. Shōrinji, 少林寺) erreicht und dort nicht nur den Chán (Zen-Buddhismus) begründet, sondern die Mönche auch in körperlichen Übungen unterwiesen habe, damit sie das lange Meditieren aushalten konnten. So sei das Shaolin Kung Fu (korrekt Shaolin-Quánfǎ, jap. Shōrin Kempō / Kenpō) entstanden, aus dem sich dann viele andere chinesische Kampfkunststile (Wushu) entwickelt hätten.

Since karate is aware of its Chinese roots, it also likes to consider itself a descendant of that tradition (Chan, Bodhidharma, Shaolin), whose historicity lies in the dark and is disputed among historians. Nevertheless, the image of Daruma adorns many a Dōjō.

Okinawa

Karate in its present form developed on the Pacific chain of the Ryūkyū Islands, especially on the main island of Okinawa. This is located about 500 kilometers south of Japan's main island of Kyūshū between the South China Sea and the Pacific Ocean. Today, the island of Okinawa is part of the prefecture of the same name in Japan. As early as the 14th century, Okinawa, then the centre of the independent island kingdom of Ryūkyū, maintained lively trade contacts with Japan, China, Korea and Southeast Asia.

The urban centres of the island, Naha, Shuri and Tomari, were important transhipment points for goods at the time and thus provided a forum for cultural exchange with mainland China. This brought the first impressions of Chinese Kempō / Kenpō1 fighting techniques (Chinese 拳法, Pinyin Quánfǎ1, obsolete after W.G. Ch'üan-Fa, literally "method of fist", correctly "fighting technique, technique of martial arts, technique of fist fighting") to Okinawa, where they merged with the native fighting system of Te / De (okin. Tī, 手) and thus evolved into the Tōde (okin. Tōdī, 唐手) or Okinawa-Te (okin. Uchinādī - "hand from Okinawa", 沖縄手). Te literally means "hand", figuratively also "technique" or "hand technique". The original term for Tōde or Karate (jap. 唐手) can therefore be freely translated as "hand technique from the land of the Tang" (China) (but of course means the various techniques as a whole).

The different economic importance of the islands meant that they were constantly beset by unrest and rebellion. In 1422, King Sho Hashi finally succeeded in unifying the islands. To maintain peace among the rebellious population, he then banned the carrying of any weapons. From 1477, his successor Shō Shin ruled and reaffirmed his predecessor's policy of banning weapons. In order to control the individual regions, he obliged all princes to permanently reside at his court in Shuri - a means of control that was later copied by the Tokugawa shoguns. Due to the ban on weapons, the weaponless martial art of Okinawa-Te enjoyed growing popularity for the first time, and many of its masters travelled to China to further their education by training in Chinese Quánfǎ.

In 1609, the Shimazu of Satsuma occupied the island chain and tightened the ban on weapons to the point that even the possession of any weapons, even ceremonial weapons, was made a severe punishment. This ban on weapons was called katanagari ("hunting for swords," 刀狩). Swords, daggers, knives, and any bladed tools were systematically collected. This even went so far that a village was allowed only one kitchen knife, which was attached to the village well (or other central location) with a rope and strictly guarded.

The tightened ban on weapons was intended to prevent unrest and armed resistance to the new rulers. However, Japanese samurai had the right of the so-called "sword test", according to which they could test the sharpness of their sword blade on corpses, wounded or even arbitrarily on a peasant, which also happened. Annexation thus led to an increased need for self-defense, especially since feudal Okinawa at the time lacked policing and legal protections that could protect individuals from such interference. The lack of state institutions of legal protection and the increased need for defense against arbitrary acts of the new rulers thus justified an intensification and subtilization process of the fighting system Te to the martial art karate.

It took about twenty years until the great masters of Okinawa-Te formed a secret oppositional alliance and decided that Okinawa-Te should only be passed on in secret to selected persons.

Meanwhile, among the peasant population, Kobudō developed, transforming tools and everyday objects into weapons with its special techniques. In the process, the spiritual, mental and health aspects taught in the Quánfǎ were lost. Designed for efficiency, techniques that involved unnecessary risk, such as kicks to the head, were not trained. Thus, in this context, it is possible to speak of a selection of techniques. Kobudō and its weapons made from everyday objects and tools could not be banned for economic reasons alone, since they were simply necessary for the supply of the population and the occupiers.

However, it was very difficult to face a trained and well-armed warrior in combat with these weapons. Therefore, in Okinawa-Te and Kobudō, which were still taught closely linked at that time, the maxim developed to avoid being hit if possible and at the same time to use the few opportunities that presented themselves to kill the opponent with a single blow. This principle, specific to karate, is called Ikken hissatsu. The selection of the most efficient fighting techniques possible and the Ikken hissatsu principle gave Karate the unjustified reputation of being an aggressive fighting system, even the "toughest of all martial arts" (see Film and Media below).

The deadly effect of this martial art led the Japanese occupiers to again extend the ban, and also put the teaching of Okinawa-Te under draconian punishment. However, it continued to be taught in secret. Thus, knowledge of Te was restricted to small elite schools or individual families for a long time, as the opportunity to study martial arts in mainland China was available only to a few wealthy citizens.

Because the art of writing was hardly widespread among the population at that time, and one was forced to do so for reasons of secrecy, no written records were made, as was sometimes the case in Chinese kung fu styles (see Bubishi). One relied on oral tradition and direct transmission. For this purpose, the masters bundled the fighting techniques to be taught in didactic coherent units into fixed sequences or forms. These exactly given sequences are called Kata. In order to keep the secrecy of the Okinawa-Te, these sequences had to be encoded in order to protect them from non-initiates of the fighting school (i.e. from potential spies). For this purpose the traditional tribal dances (odori) were used as cipher code, which influenced the systematic structure of the kata. So every kata still has a strict step diagram (embusen). The efficiency of the coding of the techniques in the form of a Kata is shown in the Kata demonstration in front of laymen: For the layman and in the untrained eyes of the Karate beginner the movements seem strange or meaningless. The actual meaning of the fighting actions is only revealed through intensive Kata study and the "deciphering" of the Kata. This takes place in the Bunkai training. A Kata is therefore a traditional, systematic fighting action program and the main medium of the tradition of Karate.

The first known master of the Tōde was probably Chatan Yara, who lived in China for several years and learned the martial art of his master there. According to legend, he taught "Tōde" Sakugawa, a student of Peichin Takahara. A variant of the kata Kushanku, named after a Chinese diplomat, can be traced back to Sakugawa. Sakugawa's most famous student was "Bushi" Matsumura Sōkon, who later even taught the ruler of Okinawa.

20th century

Until the end of the 19th century, karate was always practiced in secret and passed on exclusively from master to student. During the Meiji Restoration, Okinawa was officially declared a Japanese prefecture in 1875. In this time of social upheaval, in which the Okinawan population adapted to the Japanese way of life and Japan opened up to the world again after centuries of isolation, karate began to push back into the public eye.

The Commissioner of Education in Okinawa Prefecture, Ogawa Shintaro, became aware of the particularly good physical condition of a group of young men in 1890 during the mustering of young men for military service. They stated that they were being taught karate at the Jinjo Koto Shogakko (Jinjo Koto Elementary School). As a result, the local government commissioned Master Yasutsune Itosu to create a curriculum that included, among other things, simple and basic kata (pinan or heian), from which he largely removed tactics and methodology of fighting, and emphasized the health aspect such as posture, agility, flexibility, breathing, tension and relaxation. Karate then officially became a school sport on Okinawa in 1902. This incisive event in the development of karate marks the point at which the learning and practice of fighting techniques no longer served only self-defense, but was also seen as a kind of physical exercise.

After the beginning of 1900, a wave of emigration to Hawaii began from Okinawa. This brought karate for the first time to the USA, which had annexed Hawaii in 1898.

Funakoshi Gichin, a student of the masters Yasutsune Itosu and Ankō Asato, excelled in the reform of karate: on the basis of the Shōrin-Ryū (also Shuri-Te after the city of origin) and the Shōrei-Ryū (Naha-Te) he began to systematize karate. In addition to pure physical training, he also understood it as a means of character building.

In addition to the above three masters, Kanryo Higashionna was another influential reformer. His style integrated soft, evasive defensive techniques and hard, direct counter techniques. His students Chōjun Miyagi and Kenwa Mabuni developed their own styles on this basis, Gōjū-Ryū and Shitō-Ryū, respectively, which would later become widespread.

In the years from 1906 to 1915, Funakoshi toured all of Okinawa with a selection of his best students and held public karate demonstrations. In the following years, the then crown prince and later emperor Hirohito witnessed such a performance and invited Funakoshi, who was already president of the Ryukyu-Ryu Budokan - an Okinawan martial arts association - to present his karate in a lecture at a national Budō event in Tōkyō in 1922. This lecture received great interest, and Funakoshi was invited to give a practical demonstration of his art in the Kōdōkan. The enthusiastic audience, led by the founder of judo, Kanō Jigorō, persuaded Funakoshi to stay and teach at the Kōdōkan. Two years later, in 1924, Funakoshi founded his first Dōjō.

Through the schools, karate soon came to the universities for athletic training, where at that time Judo and Kendō were already being taught for the purpose of military training. This development, which the Okinawan masters had to accept in order to spread Karate, led to the recognition of Karate as a "national martial art"; Karate was thus finally Japaneseized.

Following the example of the system already established in Judo, the Karate-Gi as well as the hierarchical division into student and master grades, recognizable by belt colors, were introduced in Karate in the course of the thirties; with the also politically motivated intention to establish a stronger group identity and hierarchical structure.

Due to his efforts, karate was then introduced at Shoka University, Takushoku University, Waseda University and Japan Medical College. The first official book on karate was published by Gichin Funakoshi under the name Ryu Kyu Kempo Karate in 1922. It was followed by the revised version Rentan Goshin Karate Jutsu in 1925. His main work appeared under the title Karate Do Kyohan in 1935 (this version was expanded again in 1958 to include the karate-specific developments of the last 25 years). His biography appeared under the name Karate-dō Ichi-ro (Karate-dō - my way), in which he describes his life with karate.

After World War II, through Funakoshi's relationship with the Ministry of Education, karate was classified as physical education rather than a martial art, which allowed karate to be taught in Japan even after World War II during the Occupation.

Through Hawaii and the American occupation of Japan and especially Okinawa, karate became more and more popular as a sport in the 1950s and 1960s, first in the USA and then also in Europe.

From the school Shōtōkan ("House of Shōtō"), named after Funakoshi or his authorial pseudonym Shōtō, emerged the first internationally active karate organization, the JKA, which is still one of the most influential karate associations in the world. Funakoshi and the other old masters completely rejected the institutionalization and sportification as well as the associated splitting into different styles.

Note

1 The Chinese term "Quanfa - 拳法", in Japanese "Kenpo (Kempo)", is linguistically a "compound word", a kind of syllable word standing for "拳術的技法 / 拳术的技法 - technique of Chinese fist fighting". It is often translated as "Chinese fist fighting technique", "Chinese boxing technique", "Chinese boxing", "Chinese martial arts technique", "Kungfu", etc.

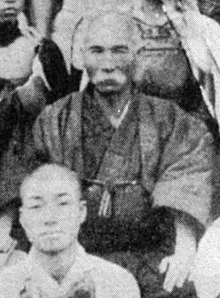

Matsumura

Itosu Yasutsune, called Ankō

Karate in Germany

In 1954 Henry Plée founded the first European Budō-Dōjō in Paris. The German judoka Jürgen Seydel first came into contact with karate at a judo course in France with Master Murakami, whom he enthusiastically invited to teach in Germany as well. From the participants of these courses, a sub-organization developed within the judo associations, which taught karate and from which the first German umbrella organization of karateka, the German Karate Federation, finally emerged in 1961.

Finally, Jürgen Seydel founded the first karate club in Germany in 1957 under the name "Budokan Bad Homburg" in Bad Homburg vor der Höhe, where Elvis Presley trained during his time in the army in Germany.

The greatest spread of karate in Germany was in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s under Hideo Ochi (until he founded the DJKB, the German offshoot of the JKA in 1993) as the national coach of the DKB and the successor organization DKV as an association of different styles. Ochi has thus significantly spread and built up karate in Germany at the end of the 20th century.

In the GDR, karate officially only played a role within the security organs: as a young sports student in the mid-1970s, Karl-Heinz Ruffert dealt with karate in his thesis at the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg - this brought him to the attention of the Ministry of State Security. As an officer of the MfS, Ruffert eventually introduced karate into the training of the domestic intelligence service. Under the leadership of the DHfK's rector, Gerhard Lehmann, karate was officially recognized as a martial art in the GDR from 1989 onwards and was incorporated into the German Judo Association.

Shōtōkan is by far the most widespread karate style in Germany today, followed by Gōjū-Ryū. Since the turn of the millennium, there are also increasingly individual Dōjō in Germany, where different Okinawa styles are trained, for example Matsubayashi-Ryū.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is Karate?

A: Karate is a Japanese martial art that uses all parts of the human body as a weapon such as the hand, fist, elbow, leg and knee.

Q: Where was Karate developed?

A: Karate was developed in the former Ryūkyū Kingdom, which is now Okinawa Prefecture.

Q: What are the main sections of Karate training?

A: Karate training has three main sections.

Q: What are the different parts of the human body used in Karate?

A: The different parts of the human body used in Karate are the hand, fist, elbow, leg, and knee.

Q: Is Karate a form of self-defense?

A: Yes, Karate is a form of self-defense.

Q: What makes Karate unique from other martial arts?

A: Karate is unique from other martial arts because it uses all parts of the human body as a weapon, such as the hand, fist, elbow, leg, and knee.

Q: What is the history of Karate?

A: Karate was developed in the former Ryūkyū Kingdom, which is now Okinawa Prefecture. The practice has its roots in traditional Chinese martial arts and was brought to Okinawa where it was further developed into the martial art we know today.

Search within the encyclopedia