Justice

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Justice (disambiguation).

The concept of justice (Greek: δικαιοσύνη dikaiosýne, Latin: iustitia, French: justice, English equity and justice) since ancient philosophy in its essence denotes a human virtue, see theories of justice. Justice, according to this classical view, is a standard of individual human conduct.

The basic condition for human behaviour to be considered just is that what is equal is treated equally and what is unequal is treated unequally. Whereby in this basic definition it remains open according to which value standards two individual cases are to be considered equal or unequal to each other.

In the knowledge that no human being can claim to act justly at all times and from all points of view, the view that justice was not a human but a divine quantity prevailed in the Middle Ages. According to this view, justice could only exist in heaven and not on earth. In the Renaissance, the divinity of justice was replaced by the idea of a natural law. In principle, justice was already inherent in nature and man had to strive to recognize this justice.

Against this, the philosopher Immanuel Kant formulated his ethics of reason from the position of the Enlightenment. A divine or natural justice are not reasonable categories, because both are fundamentally not or at least not completely recognizable for man. According to the categorical imperative, a person acts justly if he gives an account of the maxims of his actions by exerting his intellectual powers and acts accordingly, provided that these maxims of his actions can also be elevated to the status of general law.

It is also part of the modern concept of justice that it is not only applied to the individual actions of people, but also to the sum and interaction of a multitude of human actions in a social order. In the abstract, a social order is just if it is designed in such a way that individuals are free to behave justly.

The concept of justice is further extended from a social point of view to social justice. This term no longer denotes a human virtue, but a state of a society, whereby it is not a question of the individuals in this society being free to behave justly - in the sense of virtuously - themselves, but rather of each member of society being enabled to participate in society through the granting of rights and possibly also material means.

Justice is regarded worldwide as a basic norm of human coexistence; therefore, in almost all states, legislation and jurisprudence refer to it. In ethics, in the philosophy of law and social philosophy, as well as in moral theology, it is a central theme in the search for moral and legal standards and for the evaluation of social conditions.

In Plato's understanding, justice is an inner attitude. For him, it is the outstanding virtue (cardinal virtue), according to which everyone does what is his duty, and the three parts of the soul of man (the desiring, the courageous and the rational) are in the right relationship to each other. Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, on the other hand, emphasized that justice is not merely a (character) virtue, but must always be thought of in relation to others (intersubjectivity). Acts such as charity, mercy, gratitude or caritas go beyond the realm of justice (supererogation).

In recent theories of justice, egalitarianism, libertarianism and communitarianism oppose each other as basic positions.

Globalization, world economic problems, climate change and demographic developments have contributed to the fact that, in addition to questions of domestic social justice, those of intergenerational justice and a just world order have also come to the fore.

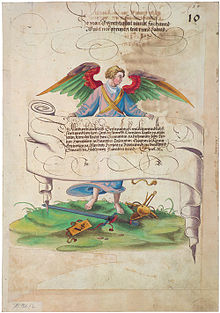

The allegorical representation of justice as Justitia, common in Western culture. She usually has three attributes: the scales (weighing, arbitrating, private law), sword (condemning, criminal law), and a bandage before the eyes (regardless of the person).

The Kiss of Justice and Peace . Unknown artist, Antwerp c. 1580

On the term 'justice

Problems of the basic definition

The basic definition of just action, to treat equal things equally and unequal things unequally, is merely formal. Whether two situations are judged to be equal or unequal to each other depends on the underlying standards of value. The concept of justice is therefore always in need of filling out.

Example 1: Women's suffrage. Women were not granted the right to vote in the early days of democracy. This was not seen as unfair because women are not men. So unequal things are treated unequally, which in principle seems fair. By today's standards of value, there is no difference between women and men with regard to the right to vote. Women are subject to democratic decisions just as men are, they carry society just as men do, and they are capable of reason and democratic decisions just as men are. It is therefore unfair if, although they are indeed equal to men in terms of democratic capacity, they are not also granted the right to participate.

Example 2: equal pay. The bible knows the parable of the workers in the vineyard as a classical story about justice. The master of the vineyard gives each worker what the master considers to be a fair wage, namely what he needs to live. He does not distinguish that some workers have worked twelve hours, but others only one. The latter, therefore, receive twelve times the hourly wage. Depending on whether the master's free decision, the needs of the workers or their performance are used as a yardstick, the remuneration appears to be just or unjust.

The general concept of justice thus incorporates different values. According to John Rawls, this harbours the danger that in a political debate about justice, those values which are particularly beneficial to one's own (class) interests will be brought to the fore. For an open discussion about justice and the values on which it is based, he therefore demands the veil of ignorance. Only those who argue independently of their own interests have a chance of devising a reasonable balance between the various value concepts that are to be incorporated into a modern concept of justice. In particular, the relationship between performance justice, according to which those who perform better than others should also live better, and egalitarian justice, according to which all people, provided with similar needs, should also have similar material opportunities, should, according to Rawls, be discussed in ignorance of one's own performance capacity or disregarding it.

Etymology and word field

In Old High German the adjective "gireht" can be traced for the first time in the 8th century. It meant "straight", "right" "fitting" (stronger form of "reht"), in Middle High German "gereht" the more abstract meaning "according to the sense of justice" is added, as already before in Gothic "garaihts". Later on "gerecht" also stands for "straightforward", "appropriate" and "according to".

Justice is a normative concept associated with an ought. It is associated with the call to transform unjust conditions into just ones. Those who want to be just have a duty to themselves, but also in the expectation of others, to act accordingly. If one recognizes justice as an imperative of morality, one bears part of the responsibility for ensuring that just conditions are established.

Injustice is a violation of justice. Injustice also includes the omission of a dutiful act. Arbitrariness is one of the main causes of injustice, because through it the principle of impartiality is broken.

Reference to different fields of action

The concept of justice is used in different contexts, for example in relation to

- human work and its results (fair wages, fair staffing),

- Judgments about actions (in court, in sports, in education),

- social rules (norms of action, laws, procedures),

- attitudes (justice as a human virtue) and

- existing relationships between persons or in society (equitable relationships).

Occasionally institutions or even emotions (righteous anger) are called righteous.

The concept of justice in earlier societies

Justice as a principle of a balancing order in a society is found in all cultures and can be traced back very far historically. Originally, justice was understood as the observance of social norms and laws. Social order was regarded as a principle of nature (natural law) or as the establishment of transcendent powers, such as a deity, who was regarded as justice personified or at least as having this quality. To be just therefore meant to fulfil the commandments of God or the gods.

Early cultures used terms that today are inaccurately and too narrowly translated as "righteous." They were religiously influenced and also included meanings such as righteous or wise, as in the Egyptian Ma'at doctrine or the ancient Israeli concept of sädäq (community faithfulness). Similarly broad is "yi" (义,righteousness), one of the four pillars of lunyu in Confucianism, which calls for an attitude that one can justify to oneself. Righteousness in these traditional teachings was understood primarily as personal righteousness, as a quality and virtue of a person within the ruling structure, which should contribute to the maintenance of the given order.

In the philosophy of antiquity, the first systematic reflections on justice are found in Plato and Aristotle. Aristotle in particular made the distinction between personal and social justice as a civic virtue. This view of personal justice was predominant until the Middle Ages. It was not until the beginning of the modern era that elaborate concepts of defining justice as a contractual relationship between people for the resolution of conflicts emerged, as in the ideas of the social contract in the mid-17th century in Thomas Hobbes or about a century later in the Age of Enlightenment in Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Justice was now no longer conceived merely as the expression of a divine order. Justice acquired the meaning of an institution for balancing different interests. Accordingly, the definition as personal justice was displaced by the view of an institutional justice, iustitia legalis.

The concept of justice was expanded and shifted with the industrial revolution and the accompanying impoverishment ("pauperization") of large parts of the population, which raised the social question. Hegel, who noted the "generation of the mob" by economic conditions, reflected on the problem philosophically and called for the abolition of "pauperism" by the public. In the emerging workers' movement, this became concrete in the demand for social justice, which has thus become the content of political disputes up to the present day.

Critique of the concept of justice

There is historically a strong change of value-related postulates. It is true that in legal-philosophical discourse the concept of justice is often used in the singular. Against this, however, it is objected that this is an illusion after the experience of numerous system and constitutional changes. According to this, the content of the concept of justice in history and the present is determined by religious or ideological pre-understandings and changes to a great extent with the change of cultures and politically established value concepts. Those who claim justice as "the" justice fail to recognize the subjectivity and relativity of value-related postulates. In a liberal state and social order, justice exists only in the plural, namely as a reflection of the different ideals of justice in society and as a competition for majority solutions to problems of design and regulation.

Ernst Topitsch pointed out the danger that the omnipresence of the category of justice in all religions, philosophies and world views ultimately leaves only a word facade. He postulated "the fact that certain linguistic formulas have been recognized through the centuries as relevant insights or even as fundamental principles of being, knowing and valuing, and still are today - ... precisely because and insofar as they have no, or no further specifiable factual or normative content." Hans Kelsen also came to a similar assessment from the point of view of legal positivism: the determination of absolute values in general and the definition of justice in particular obtained in this way turn out to be completely empty formulas by which any social order can be justified as just. Similarly, for Max Weber, the postulate of justice was "untenable from 'ethical' premises." For the systems theorist and constructivist Niklas Luhmann, too, the question of justice remains confined to the legal system. For him, "the idea of justice can be conceived as a contingency formula of the legal system" because "the preconditions of a natural law concept of justice have fallen away."

Allegory of Justice. Virgil Solis 1540/45 "If you take justice for granted, you will be well served by your people and your country."

Sculpture of the Ma'at in the Louvre

Human coexistence

Conditions of justice

In order for justice to become widely effective as an appropriate balancing of the manifold differences existing in every historical society, it is a necessary prerequisite that the existing interests and moral evaluations can be openly and unreservedly communicated. They are discussed in an open debate and subsequently translated into valid but changeable legal norms or agreements in a political process that may take different forms.

If the social norms are heteronomously (from outside, externally determined), for example by a (dictatorial) ruler or a ruling elite (for example aristocracy), people are dependent on the interests and power of a few or individuals and cannot have an equal discourse.

Secondly, as a formal basic principle, the equality (equal rights) of people must be ensured.

The so-called protection of minorities is also based on the principle of equality. It is intended to ensure that a majority does not permanently dominate individuals or minorities with regard to religion, race, gender, sexual orientation or other conditions by majority decision.

Forms of justice

Different concepts of justice play a role in different areas of human coexistence. They depend on the addressees as well as on the respective social conditions:

- Equality of all people as renunciation of discrimination of social groups on the basis of gender, sexual orientation, race, religion or other world views (principle of equality)

- Political justice in terms of freedoms, offices and opportunities both at the national and international level

- Legal justice in the form of adequate and balanced laws, an adequate administration of justice and an adequate execution of sentences (legality, legitimacy, principle of proportionality)

- Transitional justice as appropriate compensation for violence and crimes committed in a past conflict (violations of international law)

- Justice of exchange in relation to economic relationships as well as in the evaluation of performance and counter-performance, for example in the assessment of damages and penalties (also: compensatory justice).

- Social justice as the adequate distribution of material goods, jobs and resources, including equality of opportunity or equity of opportunity through access to the objects of satisfaction of basic needs such as food, housing, medical care or educational opportunities.

- Protective justice through peacekeeping, criminal or institutionalized sanctioning of structural violence in the public and private spheres, protection of minorities as tolerance of deviations from social and cultural customs and norms (for example, for the disabled and homosexuals), and protection against assaults by others through criminal law

- Intergenerational justice in the relationship between those living today and future generations, above all by limiting public debt, sufficient investment in education and environmental protection, but also within families in the relationship between parents and their minor children and between children and their parents who have grown old.

- Environmental justice, on the one hand, as the equal distribution of environmental burdens among different regions and, on the other hand, as the participation of all those affected in political decisions that burden their environment (environmental justice).

- Gender justice as a duty to create equal opportunities between women and men in professional and private life as well as in politics and the public sphere in the sense of gender mainstreaming.

- Contributive justice as a right to participate, but also as a duty to participate

- Organisational justice in organisational psychology deals with the individual or collective perception and assessment of justice in the work context.

- Procedural justice as adherence to recognized rules without regard to the person for the preservation of legal discipline, for example in the context of criminal law, social justice or (also: rule justice in contrast to result justice)

- Formal justice is a general regulatory principle that determines a course of action by which all like cases are to be treated alike.

- Restorative justice is an alternative approach to justice and a form of conflict transformation. It is an alternative to standard judicial criminal proceedings and at the same time refers to social initiatives outside the state system. Restorative justice brings together those directly involved (injured parties, defendants) and sometimes also the community in a search for solutions. The aim is to make amends for material and immaterial damage and to restore positive social relationships.

Benchmarks of systemic justice

If the concept of justice is not applied to individual behaviour, but to a social order, then there are two possibilities: Either the social order is understood as the sum of human actions, in which case actions of people from the past are also involved (e.g. through laws and institutions created in the past), or the social order is judged as a whole from the point of view of a concept of justice to be defined and applied to it. The latter is then a systemic concept of justice, which is fundamentally different from the classical concept of virtue, if only because of its approach, and must not be equated with it.

In the case of systemic justice, however, the core definition of justice remains that what is equal must be treated equally and what is unequal must be treated unequally. Here, too, the question arises as to which value standards are used in a social order to evaluate two cases as equal or unequal. In addition, the call to action contained in the concept of justice now requires an addressee. If a situation is systemically judged to be unjust, it is not yet clear who should then act and how.

Thus, an acute emergency situation due to a natural disaster cannot be judged as just or unjust in the first place, because a natural disaster is not human behavior. However, if this distress can be dealt with or alleviated through the actions of human beings, then a concept of justice that includes empathy and mercy, as demanded by Thomas Aquinas, can declare the command to provide help to be just. Systemically, however, the next question then arises as to who should behave justly: is it the state, perhaps a branch or institution of it, is it the international community of states, is it the neighbor who is closest to the sufferer spatially or on the basis of personal relationships, is it a community of people to be defined in whatever way, is it everyone who knows about the suffering in the same way, or is help most justly to be organized by a community of insured persons?

Before the question of the addressee, however, the question of which values fill out the concept of justice is particularly important in the case of systemic justice. Although obviously egoistic objectives, which express themselves e.g. in corruption and arbitrariness, are already excluded from the basic definition of justice, beyond that no general objectives can be derived from the basic definition. Virtually any well-meaning goal for a social order can also be defined as just. If a goal that is recognized as good justifies unequal treatment, then the preference fits under the aspect that unequal things must be treated unequally.

Against this background, different objectives postulated as just can be grouped into different concepts of justice, which in turn can then be defined in different ways. These are, for example:

- egalitarian justice

- social justice

- Performance equity

- ecological justice

- Generational justice

- Contractual justice

- Procedural justice

In the process, these different concepts of justice come into conflict, revealing that different values in a society lead to conflicts, especially conflicts of interest.

For example, subsidising goods that are only purchased by wealthy people may seem unfair from the point of view of egalitarianism, but fair from other, e.g. ecological, points of view. This applies, for example, to photovoltaic systems, which are only purchased by homeowners, or expensive electric cars, which are also not purchased by low-income earners. Also, the pension at 63, introduced in Germany as a life benefit pension, which almost exclusively benefits people who can expect a far above-average pension anyway, can be seen as fair in terms of benefits, even if it is diametrically opposed to egalitarian considerations and considerations of intergenerational justice.

Criteria of justice

The social function of debates and conceptions of justice is to enable value judgments about distributions or allocations within human relationships. The yardstick for this can be what someone needs according to his own opinion or that of others, what he has a right to, or what he deserves.

There are many criteria according to which the measure of justice can be assessed. Such criteria are defined according to different distribution principles, which are often chosen depending on the concrete decision-making situation:

- Needs principle, i.e. meeting the - different/different sized - needs.

- Contractual principle, i.e. doing justice to what has been agreed upon

- Performance principle, i.e. those who contribute a lot to the community are entitled to more.

- Principle of equality, that is, everyone gets the same - egalitarianism.

- Random principle, i.e. everyone is given the same chance (choice by lot)

- Principle of equality, i.e. equalisation of rights and opportunities - for example between men and women.

- Maximin principle, i.e. the worse-off receives at least what the worse-off would have received in a different distribution (called the difference principle in John Rawls' work).

- Sustainability principle as a principle of environmental ethics, i.e. not to consume more than will grow back in natural resources.

- Communist principle, that is, each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.

- Authoritarian power principle, that is, to each is forcibly assigned his own.

In contrast to the principle of distribution, which is oriented towards the recipient, the principle of subsidiarity refers to the giver of goods and services. It states that everyone should first help themselves as much as possible. This includes the duty of the individual to make his contribution to the community according to the possibilities given to him. Only if (basic) needs are not met in this way is the community obliged to provide compensation. The idea of subsidiarity underlies, for example, German social assistance. Moreover, the principle of subsidiarity states that the higher level of the community is not responsible where the lower level can solve tasks on its own responsibility. In this sense, the principle is fundamental for the relations of the Federal Government, the Länder and the municipalities in Germany, but also for the institutions of the European Union vis-à-vis the Member States.

The multitude of ideas on justice shows the breadth of the subject and at the same time its problematic nature. None of the individual principles is suitable for resolving all conflicting interests to everyone's satisfaction. Representatives of individual approaches tend to point out above all the disadvantages of alternative designs. Depending on the justification of the different postulates, which are related to the lifeworld of their originators, different value judgements are made. The question of weighting is significant for many practical areas of life when it comes to correcting conditions that are considered unjust. This concerns educational opportunities as well as co-determination in companies, tax justice, a fair wage or the assessment of just punishments. The standard "to each his own" (suum cuique), which was already formulated in antiquity, provides a point of reference, but solves neither the problem of distribution (quantification) nor conflicts of interest. Ludwig Erhard refers to the danger of misuse of the term: "I have got into the habit of almost always pronouncing the word justice only in quotation marks, because I have experienced that no word is more abused than precisely this highest value."

Justice as a political task

Justice has always been a central theme of political philosophy. Thus, B. Sitter refers to the ancient pre-Socrat Anaximander, who understood justice in a comprehensive sense, as a cosmic principle of order and as an ideal of human behaviour towards all that exists. The question of justice continues to determine political thinking and the issues of practical politics in the present day. In the Western industrialized countries, questions of gender equality, cultural and individual self-determination, and justice towards animals and nature have joined the classical debates about domestic social justice, which were and are characterized by the struggle for a solution to the social question and for the creation and development of a social security system with its various branches.

Above all, however, the ever closer interconnectedness brought about by globalization has sharpened the awareness of problems with regard to international distributive justice, the realization of justice through human rights and through a just political order worldwide. Whereas international diplomacy and politics of understanding traditionally focused on war prevention, peace agreements and national trade interests, the agenda (agenda) of the United Nations as well as that of international summits and forums (World Economic Forum, World Social Forum) is today increasingly concerned with problems of poverty, climate protection, migration as well as the worldwide relocation of capital flows, corporate investments and of sector-related jobs.

The question of whether there can be "just wars" has also been and continues to be discussed in the context of international security policy and beyond.

In this context, Jürgen Habermas and others raise the question of a world domestic policy. Otfried Höffe even envisages a "world republic" in the style of Kant. Competing positions emphasize the primacy of economic, social and cultural justice. There is a broad consensus that a more just world order can only be achieved through global cooperation.

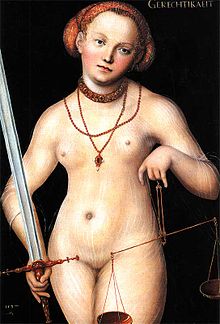

Justice as naked woman with sword and scales. Lucas Cranach the Elder 1537

Justice spiral - St. Valentinus in Kiedrich

Representation of Justice at the Tomb of Pope Clement II in Bamberg Cathedral

Search within the encyclopedia