Julius Dorpmüller

Julius Heinrich Dorpmüller (* 24 July 1869 in Elberfeld (today a district of Wuppertal); † 5 July 1945 in Malente-Gremsmühlen) was a German railway engineer and politician. From 1926 until his death he was General Director of the Deutsche Reichsbahn, from 1937 additionally Reich Minister of Transport and briefly in May 1945 Reich Minister of Post.

Dorpmüller studied railway construction and road construction at the Technical University of Aachen. After graduating, he began his career with the Prussian State Railways in 1893. In the years before the First World War he gained experience abroad in China and was soon regarded as an internationally recognised railway expert. In 1920, he was taken into the service of the Deutsche Reichsbahn, where he rose very quickly and was called upon to do the preparatory work and consultations for the Dawes Plan. In 1925, a year after the foundation of the Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft, he became deputy to the general director Rudolf Oeser, whom he succeeded after his death in 1926. After Hitler's seizure of power in 1933, he retained his post despite initial vehement criticism from SA and NSDAP members. Dorpmüller was able to preserve the internal autonomy of the Reichsbahn from interference by party authorities, but in return he implemented the National Socialist policy of rearmament and race within the Reichsbahn. He also pushed for the Reichsbahn to take over the construction of the Autobahn. From 1937 he was also Reich Minister of Transport.

During World War II, Dorpmüller remained top Reichsbahn official, despite various attempts, most notably by Albert Speer, to replace him. Under his leadership, the Reichsbahn achieved the greatest transport performance in its history. At the same time, under Dorpmüller, it also ensured the supply of the Wehrmacht on all fronts of the war and was involved in the transport of the victims of the Holocaust to the extermination camps. The Western Allies initially earmarked the Reich Minister of Transport, mindful of his good reputation from pre-war times, to head the reconstruction of the Reichsbahn. However, Dorpmüller, who was already seriously ill, died shortly after the end of the war.

For years after the war, the board members of the German Federal Railways and many railwaymen saw Dorpmüller above all as an exemplary expert whose memory was held in high esteem. It was not until the 1980s, when the role of the Reichsbahn and its general director in the crimes of the Third Reich was increasingly addressed and processed by historians, that the Bundesbahn distanced itself from him.

Julius Dorpmüller (1939)

Live

Youth and education

Julius Dorpmüller was born in Elberfeld as the eldest son of the railway engineer Heinrich Dorpmüller (1841-1918) and his wife Maria Anna, née Raulff (1839-1890). His father came from a Westphalian family and had grown up in Unna. He had entered the service of the Prussian State Railways the year before his first son was born. Heinrich Dorpmüller succeeded in advancing to the position of operating engineer, and was also active as an inventor of various railway engineering aids. His Dorpmüller sliding knife was awarded a prize by the Association of German Railway Administrations in 1882 and was subsequently used by many administrations.

After Julius, his siblings Maria (1871-1966), Heinrich (1874-1935) and Ernst (1877-1958) were born. His father was transferred to Mönchengladbach in 1871 and to Aachen a few years later. Julius Dorpmüller attended school in both cities, graduating from the Kaiser-Karls-Gymnasium in Aachen in 1888. He then studied railway and road construction at the RWTH Aachen from 1889 to 1893. His brothers also studied there and later joined the railway service. All three brothers belonged to the Corps Delta Aachen. In this corps, Dorpmüller made connections with some of his later colleagues and employees; his predecessor as Reich Minister of Transport, Paul von Eltz-Rübenach, was also a member of the corps at this time.

To continue his education after the first state examination, Dorpmüller entered the service of the Royal Railway Directorate in Cologne as a government construction foreman in 1893. He performed military service from 1894 to 1895 as a one-year volunteer with the 5th Westphalian Infantry Regiment No. 53. In 1897 he took part in the competition for the Schinkel Festival 1898 of the Architects' and Engineers' Association in Berlin as one of 14 engineers in the task of designing a seaport at the mouth of a river subject to the ebb and flow of the tide. His work was awarded a Schinkel medal and at the same time counted as a test project for the second state examination (Assessor), which he passed in the summer of 1898. After his appointment as a government master builder in the engineering field, Dorpmüller moved to the Saarbrücken Directorate, where he was taken on in the regular service on December 30, 1903, with simultaneous appointment as a railway construction and operations inspector. His duties included the reconstruction planning for the main stations of Saarbrücken and Neunkirchen. His superiors certified him in 1905 as being "eminently suitable for any managerial position".

Dorpmüller took leave of absence in 1907 and entered the service of the Chinese Shantung Railway in Tsingtau as head of the technical office. In 1908, he became the German chief engineer for the construction of the Imperial Chinese State Railway Tientsin-Pukow, which was financed by German and British loans and went into full operation in November 1912 with the completion of the Luokou Railway Bridge, the first railway bridge across the Yellow River by the MAN plant in Gustavsburg. Dorpmüller had been in charge of the operation of this railway since 1912. In 1910, the Prussian King conferred on him the character of Baurat during his stay in Tientsin.

The First World War interrupted the connections to Germany. Dorpmüller was initially able to continue his work. In 1917 he was relieved of his duties due to China's declaration of war against the German Empire and returned to Europe in 1918 disguised as a Dutch missionary via Manchuria and the Trans-Siberian Railway. On his return in May 1918, he enlisted in the German railway troops in Berlin. He was ordered to Bucharest with the Balkan Platoon and served as part of the German Caucasus Force under General Kreß von Kressenstein in Georgia. Dorpmüller was active there in light railroading in the organization of the Transcaucasian railroads.

Ascent to Reichsbahn Director General

Even before the end of the First World War, Dorpmüller was appointed to the position of government and construction councillor in Saarbrücken in July 1918, as a member of the Central Railway Office and the Railway Directorate there. From January 1919, he was the head of the construction department of the Stettin railway directorate. As early as December 23, 1919, he went to the Essen Directorate with a simultaneous appointment by the Prussian State Government to the rank of Oberbaurat (senior civil engineer). He had to abandon his plans to return to China as an adviser to Krupp after Krupp failed to win the contract to rebuild the railway bridge over the Yellow River that had been destroyed in the war. As part of the Länderbahnen, the Prussian State Railways were absorbed into the newly founded Deutsche Reichsbahn on April 1, 1920, and Dorpmüller was taken on in its service. In the following year he was the German representative in negotiations with the Reparations Commission on the financial valuation of the rolling stock handed over to the Allies after the Armistice.

Reich Transport Minister Wilhelm Groener appointed Dorpmüller as President of the Reichsbahndirektion Oppeln on 23 May 1922. In the period after the end of the uprisings in Upper Silesia and the new border demarcation between the German Reich and Poland, Dorpmüller was thus responsible for organizing the newly founded directorate and adapting the rail network of the former Katowice Railway Directorate, which had been divided by the border demarcation, to the changed requirements in the important Upper Silesian industrial area. Likewise, in accordance with the conservative attitude of the Reichsbahn management, he was to minimise, as far as possible, the co-determination of the Reichsbahn staff that had been introduced since 1918. Dorpmüller proved equal to these tasks, but also made an enemy of the railway unions at an early stage.

In preparation for the Dawes Plan, the new Minister of Transport Rudolf Oeser sent Dorpmüller as an expert to the London Conference in May 1924. He was also subsequently involved in the deliberations on the new Reichsbahn Act, which transformed the Deutsche Reichsbahn into a joint-stock company called "Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft". This company was to use its profits to pay the reparations to which the Reich had been committed in the Treaty of Versailles. As a joint-stock company, the Reichsbahn was to operate economically and largely independently of political influence. The Reich, as the owner, had a say only through the Reichsbahn Administrative Council, which also included representatives of the victorious powers and the business community. The Dawes Plan and the politicians and experts involved in it on the German side were fiercely attacked by both the Völkische and the National Socialists. Dorpmüller, as a representative of the "Dawes Railway", was also attacked by National Socialists such as Gottfried Feder or Hans Buchner, a business editor of the Völkischer Beobachter.

From October 1, 1924, Dorpmüller was president of the Reichsbahndirektion Essen, where he had to deal primarily with the consequences of the Belgian-French occupation of the Ruhr. Due to the occupation, the directorate had its headquarters in Hamm at that time. In accordance with the decisions of the London Conference, after the Dawes Plan came into effect, the directorate gradually ended its operations by 16 November 1924, and the railways in the Ruhr region returned to German operation after an interruption of almost two years. Dorpmüller mastered this difficult task extremely successfully and thus recommended himself for higher functions.

At the request of the seriously ill General Director and former Reich Minister of Transport Rudolf Oeser, who had been in office since September 1924, the Board of Directors of Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft created the post of permanent deputy to the General Director in 1925. Dorpmüller was appointed to this post on 1 July 1925, and was confirmed by Reich President Paul von Hindenburg as early as 3 July 1925. Due to Oeser's frequent absences due to illness, Dorpmüller was soon de facto in charge of the Reichsbahn alone. On 10 December 1925, at the request of the Faculty of Civil Engineering, the Technical University of Aachen awarded him the dignity of Dr.-Ing. e. h. in recognition of his services to the railway industry and to the reputation of German technology and its export opportunities abroad. Dorpmüller was a bachelor, his sister Maria kept house for him.

On 4 June 1926, just one day after the death of his predecessor Rudolf Oeser, he was elected General Manager by the Administrative Board of Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft. This quick election provoked criticism, especially from the trade unions, because Dorpmüller had dealt rigidly with co-determination rights in Oppeln and was also regarded as a "man of big industry". The Reich government itself had considered former Reich Chancellor Hans Luther and Reich Transport Minister Rudolf Krohne. In the Reichstag, the swift approach, perceived as impious, met with fierce criticism. The Reich government also felt ignored and saw its influence over the Reichsbahn endangered. Reich Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann judged Dorpmüller unsuitable after the latter had claimed in a speech to the Reichsverband der Deutschen Industrie (RDI) that the Reichsbahn's freight tariffs could be reduced by 27% without the Dawes Plan. Stresemann thus saw his fulfilment policy endangered. Dorpmüller's appointment had in fact been driven primarily by industrial representatives on the board of directors, in addition to the chairman Carl Friedrich von Siemens, above all by Paul Silverberg, a representative of the Rhenish lignite industry, and the steel industrialist Peter Klöckner. The influential Vice Chairman of the Board of Directors, Karl von Stieler, who came from the ministerial bureaucracy, also wanted to avoid a politician as Director General at all costs. Because of this public discussion, Minister Krohne delayed the submission of the confirmation to the Reich President. Hindenburg wanted the personnel problem solved and put pressure on the Reich government. His Secretary of State, Otto Meissner, together with Siemens and Krohne, finally drafted an agreement that in the future provided for at least the appointment of the deputy general director by the Reich President as well as early consultations in a future selection of the general director. Dorpmüller's speech at the RDI was described as an error that would not occur in the future. The new Director General was finally confirmed by Hindenburg on this basis on 19 October 1926. The Board of Directors confirmed Dorpmüller in office several times in the following years, most recently in 1935.

A series of accidents in the summer of 1926 contributed to the criticism of Dorpmüller's appointment, which raised doubts about operational safety in both the right-wing and left-wing press. Apart from the railway accident at Langenbach, the railway assassination at Leiferde with 21 deaths was particularly spectacular. After an anonymous letter initially suggested an act of revenge by a dismissed Reichsbahn employee, Die Rote Fahne, the party paper of the KPD, wrote of a "record of lies by the Dorpmüller press".

As general manager, Dorpmüller knew how to surround himself with capable employees, whom he also gave great freedom of action. His press officer Hans Baumann developed new ideas for transport advertising, such as the "Reichsbahn Calendar" designed by Jupp Wiertz. The head of the department for the passenger train timetable, Alfred Baumgarten, developed an essential medium for the sale of transport services with the timetable book, which was published for the first time in 1927. He appointed Max Leibbrand as the Reichsbahn's chief operating officer, who made his mark with the introduction of the "Flying Hamburger".

Reich President Hindenburg, who had been involved in Dorpmüller's appointment, appreciated the naming of the Hindenburg Dam and kept in close contact with the new general director in the years that followed, who was a frequent guest in the president's box at the Berlin State Opera on Unter den Linden. Dorpmüller also frequented Berlin's social life and acquired a certain reputation as a hard-drinking entertainer. Internally, Dorpmüller focused primarily on the rationalization and modernization of the Reichsbahn, which was also accompanied by staff reductions. While the state railways still had a good one million employees in 1918, by 1927 this number had fallen to around 710,000. The number of Reichsbahn directorates was also reduced. In 1930 Würzburg and 1931 Magdeburg lost their directorates in the face of fierce resistance from the states concerned. Dorpmüller, on the other hand, did not succeed in dissolving the Bavarian Group Administration, which Bavaria had secured as a separate intermediate authority when the state railways were merged. The economic upswing in the second half of the 1920s enabled Dorpmüller both to fulfil the reparation obligations of the Dawes Plan and to take noticeable steps towards modernising the Reichsbahn. In the end, despite all the criticism, railwaymen and their unions did not deny him respect: one union newspaper wrote on his 60th birthday: "For railwaymen Dorpmüller is a man of the trade who has seen the world and who also knows how a railway must be built." Right-wing forces in particular, on the other hand, continued to revile him as an accessory to "fulfillment politics." They also criticised his salary, which at 122,000 Reichsmarks was far higher than that of the Minister of Transport at 35,000 Reichsmarks, for example Adolf Hitler in a speech at an NSDAP event on 3 June 1927. Dorpmüller, notwithstanding the criticism at home and abroad, appeared many times as a representative of the Reichsbahn, including on visits to foreign railway administrations or as host of the second World Power Conference in Berlin in 1930. The Reichsbahn Director General spoke fluent English and French and had extensive international contacts. The League of Nations therefore made him chairman of a commission for public works of international importance in 1931.

Exemplary for the limited possibilities under the framework conditions of the Dawes Plan is the hesitant progress in the electrification of the Reichsbahn network. Dorpmüller, who was certainly open to technical experiments such as the high-pressure locomotive H 02 1001 or the rail zeppelin - with which he himself made a trip on 14 October 1930 - saw very great economic advantages in the possible reduction of operating and personnel costs. However, it was not possible for the Reichsbahn to raise the required high initial investment to the desired extent. The share of the electrically operated network therefore remained comparatively small compared to many European countries such as Italy, France or Switzerland until the Second World War.

The world economic crisis and the Schenker contract

From 1930 onwards, the Reichsbahn's transport services fell rapidly due to the world economic crisis. In 1932, the Reichsbahn made losses for the first time. In addition to the generally necessary revival of the economy, the Reichsbahn management saw a way out of this crisis in combating the competition from road transport that had emerged in the 1920s. Even before the Great Depression, freight transport by truck in particular was already causing the Reichsbahn problems as a competitor. In 1930, Dorpmüller put the loss of revenue from truck traffic at around 250 million Reichsmarks. He demanded legal measures to protect the Reichsbahn, above all through stricter licensing regulations for trucking companies and an increase in motor vehicle tax. In particular, Dorpmüller opposed undercutting of railroad rates by trucking companies. Although the government had slightly increased the gasoline and benzene taxes, Dorpmüller considered this insufficient.

At the same time, Dorpmüller also took action against road competition in other ways. The Reichsbahn had already established close relations with the Schenker forwarding company since 1925 and granted it a loan of 17 million Reichsmarks. In February 1931, Schenker and the Reichsbahn concluded the so-called "Schenker Contract", which gave Schenker a monopoly as a cartage contractor for the delivery and removal of general and express cargo at German railway stations. It could exercise this monopoly itself or pass it on to local companies. Since, in view of the road network and the state of technical development of trucks at the time, long-distance freight transport was handled almost exclusively by rail, the Reichsbahn had the opportunity here to hit the freight forwarding industry hard. Its aim was to secure a quasi-semi-public monopoly in road transport by setting tariffs in conjunction with the contract. Secretly, moreover, the Reichsbahn had already bought out the Schenker company in January 1931. Dorpmüller emphasised to the public that the contract was primarily intended to reduce the transport costs of the German economy. Criticism from freight forwarders, chambers of commerce and Reichstag deputies was considerable, and many companies feared their ruin.

On February 18, 1931, the General Manager had to answer questions to the Reich Cabinet. He informed Reich Chancellor Heinrich Brüning and the ministers about the contract and the purchase of the Schenker company. The cabinet felt snubbed by the Reichsbahn; Reich Transport Minister Theodor von Guérard had not been informed by Dorpmüller beforehand - unlike the Reichsbahn Administrative Council. Guérard accused Dorpmüller of deception, saying that the purchase contract had to be approved by the Reich government. The cartage contract with Schenker was merely a sham contract to mislead the public. Nevertheless, Dorpmüller was able to convince the cabinet at the meeting to keep the purchase contract secret.

Ultimately, the Reichsbahn had to open up the Schenker contract to other haulage companies. These could join the contract at the same conditions. Dorpmüller also asked for approval of the Schenker contract in published correspondence. At the same time, the board of directors under Carl Friedrich von Siemens sought approval for the Schenker purchase from the Reich government in confidential correspondence. At the same time, the Reich government passed a new ordinance that made all long-distance freight transports over a distance of 50 kilometers subject to approval, but the Reichsbahn had to waive certain low tariffs in order to undercut truck transport. It subsequently became apparent that freight forwarders were able to creatively circumvent the new regulations, for example by designating them as long-distance works transport.

Brüning held the Reichsbahn General Director in high esteem and considered him as Minister of Transport for his second cabinet. Due to the Schenker contract and the public discussion, he refrained from doing so and appointed Gottfried Treviranus as Reich Minister of Transport. It was then up to him to approve the amended Schenker contract on 6 December 1931, after the freight forwarding industry had also signalled its approval. The new contract came into force in March 1932. However, the contract did not bring about a lasting solution to the conflict between rail and road, as Dorpmüller had hoped.

In the Third Reich until the beginning of the war

Dorpmüller as controversial general director

During the National Socialist era, Dorpmüller, who was not a party member until 1941, was appointed Reich Minister of Transport on 2 February 1937. After Hitler's seizure of power, this did not seem to be the case at first. Shortly after Hitler came to power, the associations of haulage companies and freight forwarders had complained to the new Reich Chancellor about the Schenker contract and demanded its withdrawal. Dorpmüller was able to convince Hitler in March 1933 to retain the contract. On the other hand, Hitler rejected a monopoly for road haulage requested by Dorpmüller.

More critical for Dorpmüller was the criticism that had been voiced for years by NSDAP representatives against the Reichsbahn and him as General Director. As a company acting largely independent of the will of the Reich government, the Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft had not complied with many requests for job creation measures, special tariffs and other benefits. The "NS-Fachschaft Reichsbahn" had criticized this "industrial affiliation" and "fulfillment policy" many times. Another thorn in the side of the National Socialists was the employment of Jews by the Reichsbahn and its subsidiaries. Before 1933, Dorpmüller had selected his employees exclusively on the basis of professional criteria, and Ludwig Homberger, an internationally recognized financial expert, was a baptized Jew on the Reichsbahn board. The head of the Reichsbahn's Central Office for Purchasing, Ernst Spiro was also Jewish, as was the head of the passenger train timetable Alfred Baumgarten and Marcell Holzer, the director and former co-owner of the Schenker freight forwarding company.

The NSDAP members at the Reichsbahn, who were predominantly to be found in the middle and lower ranks, very soon became active against Dorpmüller. As early as March 1933, the Nazi faculty in the Reich Chancellery handed over a petition demanding, among other things, the removal of all Jews from Reichsbahn headquarters and a review of directors' salaries. Reichsbahn architect Richard Brademann, an NSDAP member since 1931, submitted a list of all allegedly Jewish employees. On April 6, 1933, an SA squad even briefly occupied the headquarters in Berlin's Voßstraße, repeated the demands and demanded the resignation of the board of directors.

However, Dorpmüller, whose national conservative political views, still rooted in the Empire, were well known in the Weimar Republic, had the backing of Reich President Hindenburg. Like many representatives of the conservative elites, he also quickly adapted to the new circumstances and deliberately sought an alliance with "moderate" National Socialists. The deliberately non-political orientation of the Reichsbahn and many railwaymen as an enterprise serving the whole people - without prejudice to the economic objectives under the framework conditions of the Dawes Treaty - contributed to this rapid adaptation. Formally, the form of organisation under this treaty, which was binding under international law, remained in place until 1937, but, like the Weimar constitution, it was in fact rendered inoperative by complete political control on the part of the National Socialist regime. With an appeal to the railway workers on the occasion of the passing of the Enabling Act, Dorpmüller sided unreservedly with the "national government" as early as 24 March 1933.

This did not appease the criticism of Dorpmüller by the more radical National Socialists. The General Director therefore turned to Hitler and Transport Minister Paul von Eltz-Rübenach. Hitler, who was dependent on a functioning transport system and wanted peace in this area, commissioned the SA leader Rolf Reiner in May 1933 to form a "NSDAP leader's staff at the Reichsbahn" to investigate the accusations made against Dorpmüller and the Reichsbahn management and to establish calm. The NS-Fachschaft was initially prohibited from further activities against the Reichsbahn leadership. Despite the ban, thousands of Reichsbahn workers gathered in front of the Nuremberg Transport Museum on June 21, 1933, for a demonstration with slogans such as "Away with Dorpmüller", "Out with the Jews" and "We receive 18 Mk a week, Dorpmüller 100000 Mk". In Berlin, National Socialist railway workers reacted to the announcement that Reiner, together with Dorpmüller and Carl Friedrich von Siemens, had taken the "Gleichschaltung" of the Board of Directors "into consideration" with spontaneous demonstrations in Voßstraße in front of the headquarters. Hitler had to receive and reassure the leaders of the Nazi party in the neighboring Reich Chancellery.

Dorpmüller finally managed to win Hitler's support for his remaining in office. Not only did the support of Hindenburg and Eltz-Rübenach contribute to this, but Dorpmüller's willingness to meet the regime's expectations had also prepared the ground for this. At the management level and on the Board of Directors, disagreeable members were now replaced or dismissed and replaced by National Socialists loyal to the line. Dorpmüller quickly got rid of almost all "non-Aryan" employees or those who were otherwise not agreeable to the new rulers. As early as May 1933, he promoted Wilhelm Kleinmann, who had been a member of the NSDAP since 1931, from his previous post as head of the Oberbetriebsleitung West to president of the Reichsbahndirektion Köln. In Mainz, Erfurt and Regensburg, too, railwaymen with NSDAP party membership moved to the top of the directorates. The previous representative of the general director and personnel director Wilhelm Weirauch, who was particularly criticised because of the staff cuts during the world economic crisis, was replaced by Kleinmann on 25 July 1933. Dorpmüller proposed other party comrades, but was not able to prevail with all personnel proposals in the conservative-dominated Board of Directors. In cooperation with Kleinmann, who appeared ostentatiously in SA uniform and whose professional competence was not in doubt, the Reichsbahn boss succeeded in calming the situation in the following months. Last but not least, Dorpmüller's quick willingness to take over the construction of the Reichsautobahnen with the Reichsbahn helped stabilize his position in the polycratic power structure typical of National Socialism. After the death of Hindenburg on 2 August 1934, at whose funeral he attended at the Tannenberg Memorial, Dorpmüller called on railway workers to vote in the subsequent referendum to combine the offices of Reich Chancellor and Reich President, and swore in Reichsbahn headquarters officials to Hitler as "Führer and Reich Chancellor". In September 1934, after intervening with Eltz-Rübenach and Martin Bormann, Dorpmüller was finally able to obtain Rudolf Hess's consent to dissolve the Führer's staff. He had ultimately defended the internal autonomy and sole professional responsibility of the Reichsbahn, but in return he had accepted that the Reichsbahn implemented and represented the National Socialist ideology and the policies of the Third Reich without circumstance. This compromise was to last until the end of the Third Reich in 1945.

Implementation of National Socialist policy at the Reichsbahn

One of the first steps towards a National Socialist policy was the removal of all "non-Aryans" from the service of the Reichsbahn. Although the Reichsbahn, which was not formally a Reich authority until 1937, was not obliged to apply the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service enacted in April 1933, it did so under Dorpmüller's leadership. It did so nevertheless under Dorpmüller's leadership. Only civil servants already employed before 1914 were initially spared, and the Reichsbahn also applied the front-line fighter privilege. Dorpmüller's personal staff, such as his press chief Hans Baumann, and senior civil servants in the main administration, such as Alfred Baumgarten and Ernst Spiro, were quickly transferred to lower-ranking posts, dismissed, or retired "at their own request", even if they fulfilled the conditions of the Berufsbeamtentumgesetz. The only exception among the "non-Aryan" higher Reichsbahn officials was Ludwig Homberger, whose expertise even the new deputy general manager Kleinmann initially considered indispensable. Dorpmüller also recommended the resignation of Silverberg, a member of the board of directors who, like Homberger, was of Jewish origin. Many Social Democrats, Communists and trade unionists also lost their jobs, and some, such as the trade unionist and board member Matthäus Herrmann, were imprisoned. In exchange, unemployed people were hired through job-creation schemes, with NSDAP members and old fighters in particular benefiting. The "German salute" was introduced at the Reichsbahn on Dorpmüller's instructions as early as July 15, 1933 - however, this order had to be partially withdrawn again after a few weeks because of confusion with the hand signals of the train crew during the brake test.

The construction of the Reichsautobahnen was another element of National Socialist policy, the implementation of which Julius Dorpmüller embraced almost unreservedly. Dorpmüller had already participated in the first events of the Hafraba Association in 1927 and had maintained contact with its managing director Willy Hof. As Reich Chancellor, HeinrichBrüning had already discussed plans to have the Reichsbahn finance the construction of the autobahn and then refinance it through a toll, which Dorpmüller had still opposed. Hitler adopted these plans and involved the Reichsbahn under Dorpmüller's leadership. After initial resistance, Dorpmüller saw this as an opportunity both to strengthen his personal position and to decide the competition with the private freight industry in favour of the railways. Hitler promised him that the Reichsbahn would be responsible for the uniform management of all long-distance freight traffic. On August 25, 1933, the Gesellschaft zur Errichtung der Reichsautobahnen was founded as a subsidiary of the Reichsbahn, and Julius Dorpmüller became Chairman of both the Executive Board and the Board of Directors of the new company. As early as June, Dorpmüller had travelled to Italy at the head of a large delegation together with Reich Labour Minister Franz Seldte to study the construction of motorways there.

Dorpmüller received a rival for Hitler's favour and responsibility for motorway construction with the appointment of Fritz Todt as "Inspector General for German Roads". In this position, Todt was responsible for the routing and plan approval of the autobahns. Hitler valued Todt, who had already been a party member since 1923, as a loyal and at the same time professionally competent henchman. On September 23, 1933, Dorpmüller was at least allowed to hand Hitler the spade for the ground-breaking ceremony for the construction of the first section of the Reichsautobahn between Frankfurt and Heidelberg. The Reichsbahn General Director was also often present at other ground-breakings and opening ceremonies, but in the public perception he usually took a back seat to Hitler and Todt as well as other party VIPs.

The Gleichschaltung of the Länder finally made it possible for Dorpmüller to realize his long-cherished wish and dissolve the Bavarian Group Administration on October 1, 1933. As compensation, Bavaria received a new Reichsbahn Central Office in Munich. The following year, as a result of the Act on the Reconstruction of the Reich, the states lost their previous rights of co-determination in the approval of railway lines as well as railway supervision. In the following years, Dorpmüller was also able to dissolve the comparatively small Reichsbahndirektionen Oldenburg and Ludwigshafen, both successors to former state railways.

Further modernisation of the Reichsbahn

The National Socialists' labour market and economic policy also included the expansion and modernisation of rail transport. Contrary to the blood-and-soil ideology of National Socialism, this expansion focused on modern technology and rationalization. However, despite its considerable strategic importance, the modernization of the Reichsbahn lagged behind the construction of the autobahns and the buildup of the Wehrmacht and the armaments industry. Building on plans and preparatory work from the Weimar period, the Reichsbahn was able to establish a good reputation as a modern transport company both at home and abroad, despite a lack of steel quotas and insufficient investment funds. In 1935 and 1936, the centenary of the first German railway, the Ludwigs-Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft from Nuremberg to Fürth, opened on 7 December 1835, and the 1936 Summer and Winter Olympic Games offered the General Director many opportunities to present the achievements of the Reichsbahn to the public. It was during this period that his reputation as "Germany's first railwayman" and the "Hindenburg of the railways" was established, a reputation that was systematically built upon in the years that followed and during the war. Dorpmüller established contacts with other railway companies and experts through various trips abroad. Among other things, major trips abroad took him to the Polish state railways in 1935, to the third World Power Conference in Washington, D.C. in 1936, including meetings with American railway directors and President Franklin D. Roosevelt, as well as to Washington, D.C. in 1937. Roosevelt, and in 1937 to Sweden, where the SJ provided him with a special train with a festively decorated locomotive as a token of its esteem.

The Reichsbahn demonstrated its claim to be a modern transportation company in 1935 in Nuremberg at the large anniversary exhibition celebrating the 100th anniversary of the commissioning of the first German railroad, where it presented its most modern vehicles such as the "Flying Hamburger" that had been running at up to 160 km/h between Hamburg and Berlin since 1933, the Henschel-Wegmann train with the DR class 61 streamlined locomotive, the new "Glass Train" and other new locomotives and cars. Julius Dorpmüller opened the exhibition on July 14, 1935, together with Transportation Minister Eltz-Rübenach, both of whom took a turn in the cab of the first German locomotive, the "Adler", which had been recreated on the occasion of the anniversary, dressed in historical costumes. Dorpmüller thus once again presented himself to the public as the supreme railwayman and leading figure. Hitler, who was otherwise a rare guest at Reichsbahn events, also took part in a large vehicle parade on 8 December in Nuremberg. Not mentioned in the Gleichgeschaltet press, however, was the fact that the Reichsbahn sent its last "non-Aryan" civil servants into involuntary retirement that year, including board member Ludwig Homberger.

The 1936 Olympic Games led to a further push for modernization. In Berlin, the first section of the north-south tunnel for the Berlin S-Bahn was inaugurated in time. The extensive services provided by the Reichsbahn to transport the masses of visitors, especially during the Berlin Summer Games, impressed many observers. For Dorpmüller, however, there was a personal loss. His younger brother Heinrich, who was responsible for the preparation and planning of the special Olympic transports at the Reichsbahndirektion Berlin, died due to overwork shortly after the games on September 1. Other parts of the Reichsbahn network were also modernised. Instead of the obsolete ferry connection to the island of Rügen, Dorpmüller inaugurated the new Rügen Dam on 5 October. In freight traffic, the Reichsbahn increasingly expanded door-to-door traffic by road rollers and container traffic as a precursor to container transport, and accelerated shunting operations with small locomotives.

The record run of the DR class 05 high-speed locomotive was used especially prominently for propaganda purposes in the same-society media of the Third Reich. On May 11, 1936, locomotive 05 002 reached a top speed of 200.3 km/h between Hamburg and Berlin, setting a world record. In addition to Dorpmüller, Transport Minister Eltz-Rübenach, Fritz Todt, Adolf Hühnlein and other prominent figures, Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler, Gestapo Chief Reinhard Heydrich and Reichsleiter Martin Bormann took part in the trip. The guest list shows how Dorpmüller and the Reichsbahn wanted to demonstrate their indispensability to the regime's most important figures by demonstrating technical prowess. At the annual Reich Party Congresses in Nuremberg, which Dorpmüller also regularly attended, the Reichsbahn handled an enormous volume of traffic and was thus also able to demonstrate its importance. For the party congress in 1935 alone, the Reichsbahn provided over 530 special trains for around 850,000 participants. These journeys, which were offered at very low fares, caused considerable deficits for the Reichsbahn, as did comparably discounted journeys for KdF journeys and group fares for the various National Socialist organisations. Despite repeated efforts, Dorpmüller was unable to obtain a fare increase or other compensatory measures from the party chancellery.

General Director and Reich Minister of Transport

On 30 January 1937, Hitler announced to the Reichstag that the Reichsbahn would be placed under the sovereignty of the Reich. With the Law on the Reorganization of the Relationships of the Reichsbank and the German Reichsbahn of 7 February 1937, Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft was renamed "Deutsche Reichsbahn" - it had already not used the suffix "Gesellschaft" in its correspondence since 1936 - and the Administrative Board was replaced by an advisory board that was merely advisory. The Reichsbahn was transformed into a special asset of the Reich. Hitler thus again released himself from obligations arising from the Treaty of Versailles. Also on 30 January, Hitler used the occasion to award several ministers and officials the NSDAP's Golden Party Badge. Reich Post and Transport Minister Eltz-Rübenach, who as a devout Catholic felt increasingly uneasy about the regime's church policies, made acceptance conditional on a change in policy toward the church. This led to his swift resignation. As early as February 2, Hitler appointed Dorpmüller, then 68 years old, as the new Reich Minister of Transportation, and the "Old Fighter" Wilhelm Ohnesorge became Postmaster General. One day later, Hitler and Dorpmüller together announced to thousands of Reichsbahn employees from the balcony of the Reich Chancellery a "Reichsbahn, free of Versailles". The French ambassador André François-Poncet, who knew Dorpmüller personally, characterized him on this occasion as follows: "Eltz Rübenach [...] relinquishes his office to Dorpmüller, a skeptic who loves the good life and easily pins on the party badge". Dorpmüller did not become a party member, however, until four years later. By becoming part of the direct Reich administration, the Reichsbahn could now dispense with the formal legal peculiarities that had previously been necessary in enforcing the National Socialist policy on Jews. The new Reich Civil Servants Act of January 1937 was applied directly at the Reichsbahn from July of the same year, which meant that by the end of that year most civil servants with "non-Aryan" spouses had been dismissed.

The Reichsbahn-Hauptverwaltung became part of the Reichsverkehrsministerium (Reich Ministry of Transport), former Reichsbahn board members became ministerial directors. The main focus in the RVM was clearly rail transport, as road transport was claimed by Fritz Todt and air transport was the domain of Hermann Göring's Reich Aviation Ministry. Shipping and motor transport played only a secondary role. Dorpmüller continued to entrust State Secretary Gustav Koenigs with this task. Dorpmüller's deputy Wilhelm Kleinmann became the second State Secretary. Not least because of Dorpmüller's new position, the Reich Motorway Act was amended in 1938, as Dorpmüller, as Minister of Transport, could no longer be Chairman of the Board of Management of the motorway company - as his competitor Fritz Todt was authorised to issue instructions to him. Todt therefore took over the office of the board of directors, and the Reich Minister of Transport became chairman of a new advisory board of the company by law.

In the following year, the takeover of the BBÖ after the Anschluss of Austria was a major challenge for the Reichsbahn. Another area of conflict arising from the Anschluss in the NS-typical wrangling over competencies was bus line transport, which led to heated arguments between Dorpmüller and Post Minister Ohnesorge - both administrations had outbid each other in the acquisition of corresponding concessions in what was now the Ostmark. Prior to this, in January 1938, Dorpmüller had ordered the Reichsbahn vehicles to be equipped with the swastika eagle, and in April he issued a new "General Service Instruction for Reichsbahn Officials (ADA)", in which Reichsbahn officials were once again obliged to be loyal and obedient to Adolf Hitler and to refrain from any private dealings with Jews. In the area of the former BBÖ, its Jewish employees were simply not taken on. In the fall of this year, the takeover of the former Czech lines in the Sudetenland followed.

Even as Minister of Transport, Dorpmüller remained extremely fond of travelling. From 1938 onwards, like many other greats of the National Socialist regime, he was able to make use of his personal saloon car for the relevant journeys. In 1938 he visited, among other things, the new construction of the Müglitztalbahn in Saxony, the inauguration ceremonies of the Mittellandkanal as well as two new Rhine bridges near Speyer and Karlsruhe and other exhibitions and sightseeing events. For the 100th anniversary of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (or its oldest predecessor company) he travelled to Great Britain in November 1938. Almost at the same time, at the end of October, the Reichsbahn provided 20 to 30 special trains at short notice for the Polenaktion, with which Polish and stateless Jews were deported to Poland via the border stations Firchau, Kreuz (Ostbahn), Neu Bentschen and Beuthen O.S.. The Reichsbahn proved to be in a position to provide the corresponding train services for the security police at very short notice.

In 1939 Hitler celebrated his 50th birthday. As had been customary since 1933, Dorpmüller again assured the Führer of the Reichsbahn's unconditional loyalty and allegiance on this occasion. According to the revised law on the German Reichsbahn, enacted on 4 July 1939, Dorpmüller, as Reich Minister of Transport, also remained General Director of the German Reichsbahn. He celebrated his 70th birthday on 24 July 1939, and the Reich Ministry of Transport commissioned a bronze bust from the sculptor Helene Leven-Intze to mark the occasion. At this time Dorpmüller enjoyed a high reputation as a transport expert, and not only at home. However, there was public criticism of various traffic congestions that had occurred in the winter of 1938/39. The fact that this criticism had become public in view of the rigid equalisation of the press gave the impression abroad that this was intended to prepare in the long term for Dorpmüller's replacement by Todt. At the Reichsbahn, Dorpmüller reacted in March 1939 by launching an extraordinarily extensive procurement program for the unit steam locomotives that had been delivered in rather small numbers until then, after he had been promised the steel quotas that the Reichsbahn had demanded in vain in the previous years in Goering's Four-Year Plan. Under pressure from Martin Bormann in particular, and thus ultimately from Hitler, he was also forced to open up the Road Haulage Act and the Reich's road haulage tariff to other companies and to relax the restrictive licensing policy he had hitherto pursued for heavy truck traffic. Two days after Dorpmüller's birthday, an RVM decree ordered that Jews were allowed to use MITROPA sleeping cars with special permission, after a general ban on the use of dining cars and sleeping cars for German and stateless Jews had been issued earlier in February. Also abolished were the free travel privileges for retired Jewish Reichsbahner and their dependents. In February 1939, Dorpmüller had already signed a decree ordering the "confiscation" of the driving licenses and motor vehicle papers of Jews. He thus tacitly legalized and accepted a police order issued by Himmler in December 1938, the legal validity of which had previously been doubted by subordinate authorities. Dorpmüller, on the other hand, was more critical of Rudolf Hess's wishes to appoint only NSDAP members to senior civil service positions. The extent to which Dorpmüller judged such questions exclusively from a technical and operational point of view was shown by the proposal he made after the outbreak of war at the end of 1939 for the special identification of Jews, probably in order to simplify the enforcement of the various driving bans and restrictions in the transport sector. In the years before, the RVM had even objected to some measures of persecution of Jews when they collided with questions of reliable operation.

Dorpmüller and the Reichsbahn in the Second World War

At the beginning of World War II, Dorpmüller was the oldest minister in Hitler's cabinet at 70. However, he energetically went about the task of preparing the Reichsbahn for war and guiding it through the war, clearly professing his support for the goals of Hitler's policies. Due to illness, he was forced to cut back only from the second half of 1944, leaving the management of the Ministry and the Reichsbahn largely to his staff.

The invasion of Poland and the Eastern Railway

Shortly after the beginning of the invasion of Poland, Dorpmüller made his first appeal to the Reichsbahner. In it, he assured Hitler of the railwaymen's "unbreakable loyalty". From September onwards, Dorpmüller, who until then had usually dressed in civilian clothes, usually appeared in uniform. In the years that followed, he travelled extensively and visited the railwaymen on most of the war's fronts.

Already in October 1939, the General Directorate of the Ostbahn (Gedob) was founded. The Ostbahn in the Generalgouvernement (GG) remained legally outside the Reichsbahn, it represented a separate special asset of the Generalgouvernement. Although Dorpmüller was able to achieve in the course of the war that the Ostbahn under Adolf Gerteis, the president of the Gedob, took over the Reichsbahn organization, otherwise the Ostbahn remained a largely independent company from the Reichsbahn. Financially and economically, it was primarily responsible to the Governor General Hans Frank, the Reichsbahn only had to provide rolling stock and personnel. The technical supervision also lay with the Reich Minister of Transport, but the economic management was taken over by the GG. In the close day-to-day cooperation, this repeatedly led to friction and disputes over competencies, Dorpmüller was not able to prevail over Frank in the long term with Hitler, even though in the following years operational control was increasingly transferred to the Reichsbahn. The railways in the areas of Poland that had been German until 1919, on the other hand, were organised as new Reichsbahn Directorates in Posen and Danzig and integrated into the Reichsbahn.

The first winter of the war had exposed weaknesses in the German transport system. Inland navigation in particular was criticised, which finally led to the resignation of the responsible State Secretary Gustav Koenigs at the end of February 1940. His responsibilities for motor vehicles and maritime shipping were taken over by two new undersecretaries of state, while the department for inland waterways was placed under the responsibility of the remaining undersecretary of state, Kleinmann. But the railways were also criticized. Rumours of Dorpmüller's replacement made the rounds, Rudolf Gercke, the transport chief of the Wehrmacht, was mentioned as a possible successor. Another reaction was the upgrading of the Reichsbahn's three chief operating officers to general operating officers with additional authority over the individual Reichsbahn directorates in order to ensure more uniform operational management and planning. The so strongly propagated Reichsautobahnen, on the other hand, initially played only a subordinate role.

In the Western campaign, on the other hand, there was hardly any criticism of the Reichsbahn and the German transport system. Dorpmüller gave a laudatory speech at the Gare de l'Est in Paris on 18 July 1940 to the German railwaymen who, after the Compiègne Armistice, were to supervise the operation of the French state railway SNCF, which now operated for German interests. Earlier in May, Dorpmüller had been in Italy to take part in the centenary celebrations of the Italian railways there. Dorpmüller also travelled to other allied countries such as Slovakia that year. During this visit in December 1940, Dorpmüller, who was known to be a hard drinker, appeared visibly intoxicated at an appointment, which led to a critical letter from Reinhard Heydrich to Martin Bormann. After Dorpmüller had already received the War Merit Cross I Class in September 1940, Hitler awarded his Minister of Transport the Golden Party Badge of the NSDAP in early December. As the holder of the party badge, Dorpmüller applied for membership in the NSDAP on 28 January 1941, and on 1 February 1941 he received the membership number 7,883,826.

Transport crisis in the war against the Soviet Union

In Operation Barbarossa, which began on 22 June 1941, the Wehrmacht itself initially took over all the main transport tasks, and it also organised the field railway operations between the Reich's borders and the front. The railwaymen of the Reichsbahn who were requested for this purpose were initially under military command as Wehrmacht followers. Since the Soviet railroaders were largely able to keep their rolling stock out of German hands, the Reichsbahn soon had to send an increasing number of its own locomotives and cars to the East. In addition, the railway network, which was built in Russian broad gauge of 1,524 mm, had to be re-gauged to European standard gauge. In this situation, Dorpmüller pointed out the lack of reserves in the German transport system, but despite the support of Joseph Goebbels, he was hardly able to make any headway in the face of purely military demands. Even before the war, the steel contingents for the Reichsbahn had always been treated as secondary to direct armament, so that it had entered the war with an outdated locomotive fleet and an inadequately developed network. The Reichsbahn was only able to procure a small number of the standard steam locomotives that had already been designed in 1925; the majority of the locomotive fleet still consisted of the series of the state railroads. In terms of transportation, the rearmament had relied primarily on trucks and neglected the railroads.

In the late autumn of 1941, the Eastern campaign suffered a severe transport crisis that brought supplies to the front almost to a complete standstill in December. Severe frost led to a series of breakdowns of the German locomotives, which were not designed for such temperatures, and road traffic could hardly be maintained. Hitler finally placed the railways behind the front under the control of the Reich Minister of Transport. Dorpmüller set up an "Eastern Branch" of the RVM in Warsaw, which, with four main railway directorates in Kiev, Minsk, Riga and Dnepropetrovsk, took over the organisation and operation of the railways behind the Eastern Front. On February 19, 1942, Dorpmüller informed the railwaymen about the new task in a pithy appeal, calling it the "honorary duty of every railwayman." Prior to this, Dorpmüller had already travelled to Minsk and Smolensk in January 1942 to see the situation for himself, followed by a business trip to Kiev and Dnepropetrovsk in February.

The reorganization could not solve all transport problems, especially since there continued to be fierce disputes over authority between the RVM and General Gercke as head of Wehrmacht transport. Hitler blatantly threatened State Secretary Kleinmann with the Gestapo and finally, on 28 February 1942, had two senior Reichsbahn officials at the main railway directorates in Kiev and Minsk arrested and sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Dorpmüller interceded on behalf of his staff, but despite personal representations to Hitler, was initially unable to achieve anything. Ulrich von Hassell noted in his diary that Hitler had replied to Dorpmüller's intercession that "if he had a general and Knight's Cross winner sentenced to death and reprimanded other generals, he would probably be able to imprison some railway presidents." Both officials were not released from the concentration camp until the summer of 1942.

Albert Speer, as successor to the fatally injured Fritz Todt in the office of armaments minister, now did everything in his power to have Dorpmüller, who seemed to him to be too old and immobile, replaced. He did not succeed in this, because Hitler wanted to continue to use Dorpmüller's nimbus as a respected and recognized expert and "Hindenburg of the railways". He did, however, manage to largely remove responsibility for locomotive procurement and development from the RVM and the Reichsbahn for the time being. Instead of Richard Paul Wagner, who had previously been in charge at the Reichsbahn Central Office, a newly founded "Main Committee for Rail Vehicles" under the former DEMAG manager Gerhard Degenkolb took over responsibility for the design and production of the new class 52 wartime locomotives in March 1942. In May 1942, Speer succeeded in having the previous State Secretary Kleinmann replaced by Albert Ganzenmüller, a blood medal bearer who had distinguished himself on the Eastern Front and was considered a recognized expert. Dorpmüller, who had previously told Speer that he could "no longer assume responsibility for regulated traffic conditions in the Reich" due to a lack of sufficient wagons and locomotives, was forced to accept this change, which Hitler imposed on him on 24 May 1942. Hitler warned the Reichsbahn that the war must not be lost because of the transport problems, and that these must therefore be solved. Probably only his friendship with Hermann Göring saved Dorpmüller from being replaced. Instead, Hitler commissioned the surprised Dorpmüller with the new project of planning an oversized 3-metre wide-gauge railway to open up the conquered territories in the east.

In the autumn of 1942, Dorpmüller had to go into hospital for a longer period of time for the first time. In the day-to-day management of the Reichsbahn, he was replaced more and more by Ganzenmüller, without the Reich Minister of Transport allowing the business to be completely taken out of his hands. Both worked well together, as Ganzenmüller respected the older Dorpmüller as an experienced professional. The Reichsbahn was finally able to solve the transport crisis of the winter of 1941/42 by adapting its established operational procedures and traffic control measures to the circumstances, and these were implemented by more energetic, younger managers. In the following year, 1943, the Reichsbahn produced its highest ever freight transport performance, 178.6 billion tonne-kilometres, as well as its highest ever passenger transport performance, 107.3 billion passenger-kilometres. It was not until the Allied air raids on the Reichsbahn network intensified after the Normandy invasion that the transport figures finally dropped significantly.

Further course of the war

Although Dorpmüller had lost some of his authority, he threw himself all the more intensively into his work. In October 1942, through persistent representations to Hitler, he was given sole administration of the entire transport system on rails, roads and waterways in the Eastern territories. The previous branch office of the RVM in Warsaw was upgraded to the General Transport Directorate East on 1 December 1942. While in 1937 the Reichsbahn still owned about 54,000 km of lines, by the end of 1942 Dorpmüller was in charge of a good 150,000 to 160,000 km of railway lines in the Reich and the occupied countries. A good 1.6 million railwaymen and women were active on this network.

After an initial operation at the end of 1942, Dorpmüller initially recovered quite quickly. As early as March 1943, he was again intensively on business trips and again tried to gain stronger influence on the Ostbahn in the Generalgouvernement. The Ostbahn finally introduced an office structure based on the Reichsbahn model. Dorpmüller did not miss the opportunity to inaugurate three new presidents of the directorate himself in May 1943, but in direct conflict with Governor General Frank he had to back down and accept the economic independence of the Ostbahn. His attempt to circumvent the Ostbahn President Gerteis and achieve the possibility of direct operational instructions to the Ostbahn Directorates thus also failed.

By the summer of 1943 at the latest, Dorpmüller began to have doubts about whether the war could still be won. In his will, written in August 1943, he took into account the case of a lost war, in order to know that his sister would be provided for even then. Nevertheless, he remained active and tried to maintain the traffic in the Reich, which was increasingly affected by the air war. The minister travelled restlessly through the Reich and the allied states, visiting destroyed lines and stations and appealing to the workforce to hold out. While parts of the ministry were relocated to Groß Köris, some 40 km south of Berlin, from 1943 onwards, Dorpmüller remained in the Reich capital. Hitler rewarded his efforts with the Knight's Cross of the War Merit Cross and the "Pioneer of Labour" badge of honour. In recognition of the railwaymen, Hitler also designated 7 December (the first German railway between Nuremberg and Fürth had been opened on 7 December 1835) as the "Day of the German Railwayman". At the first celebration of this day in 1943, Joseph Goebbels was the keynote speaker.

Shortly before D-Day and the invasion of the Western Allies, Dorpmüller was in Paris for the last time and, among other things, held talks with the commander-in-chief there, Erwin Rommel. He was not involved in the conspiracy for the assassination of July 20, 1944; his name did not appear on Carl Friedrich Goerdeler's cabinet lists. Four days after the assassination, Dorpmüller celebrated his 75th birthday. Albert Speer had tried to use this as an occasion for an honorable retirement of Dorpmüller, but without success. The Gleichgeschaltete press celebrated the Minister of Transport and Reichsbahn General Director as a "faithful Ekkehard of transport" and Hitler added the swords to the Knight's Cross to the War Merit Cross.

The role of the Reichsbahn in the Holocaust

Like all other ministries, the RVM had supported all measures of discrimination against and persecution of Jews within its sphere of competence before and at the beginning of the war, most recently with Dorpmüller's order of November 18, 1941, which prohibited Jews from using public transportation without police permission. During the war, active assistance in the Holocaust was added. Almost all deportations of Jews and other victims of the war of extermination and the Nazis' racial ideology were carried out by rail. Only on shorter routes and as feeder transports motor vehicles were used. The Reichsbahn had already gained initial experience in the "Polenaktion" in October 1938. Special trains were also provided by the Reichsbahn for the Nisko Plan at the end of 1939. In October 1940, nine special trains ran to the unoccupied part of France on the order of Adolf Eichmann in the Wagner-Bürckel action.

Finally, from October 1941 onwards, the first deportation trains left the Reich for the East. Initially, the trains rolled into the ghettos of Litzmannstadt, Minsk and Riga, and from autumn 1942 onwards, the main destination was the extermination camp Auschwitz. As a rule, these special trains were ordered by the regional offices of the security police at the Reichsbahn, the coordination was mainly in the hands of Franz Novak of Department IV B 4 of the Reich Security Main Office, in close cooperation with the department head for mass transports in the RVM, Paul Schnell and his assistant Otto Stange. In addition, from the summer of 1942 onwards, the Theresienstadt ghetto became the destination for a large number of smaller transports, which were often run as special wagons in scheduled passenger trains. The trains within the Generalgouvernement to the extermination camps Treblinka, Sobibor and Belzec were run and organised by the Ostbahn, there the Reichsbahn official Walter Stier was responsible for the timetable organisation of the trains, which were ordered by the SS.

As Reich Minister of Transport and General Director of the Reichsbahn, Dorpmüller was jointly responsible for the deportation of Jews by means of the Reichsbahn. Although - in contrast to his State Secretary Albert Ganzenmüller - no correspondence in this regard has become known, it can be assumed that he was not unaware of the relevant letters, including complaints from Himmler. Dorpmüller was an extremely active man until shortly before his death, who did not let his work be taken out of his hands and was well informed about most things concerning Reichsbahn operations. Dorpmüller was probably in Auschwitz at least once in October 1944, when he went to Upper Silesia to find out about problems with the clearing of industrial plants there.

The intensive use of forced laborers, especially from the East, in the service of German industry could also only be accomplished through transports by the Reichsbahn. The Reichsbahn itself used forced laborers in many cases as early as mid-1940, some of whom were even deployed in positions of responsibility, such as locomotive drivers, due to a lack of personnel. As a rule, however, especially when they were Soviet prisoners of war, they were used primarily as track construction workers and in workshops.

End of the war and death

Soon after the beginning of the last year of the war, Julius Dorpmüller had to undergo another operation at the beginning of February 1945 due to his cancer, which was performed by Ferdinand Sauerbruch at the Berlin Charité. Albert Speer took advantage of this to have Hitler put him in charge of a new "Transport Council" a few days later, which was given overall responsibility for Reichsbahn operations. Dorpmüller once again recovered from the operation and resumed leadership of his ministry. Like many other members of the Reich government, Dorpmüller left Berlin in April 1945 shortly before the Red Army closed in and went with his sister and staff to Schleswig-Holstein, where he found accommodation in a railway school in Malente. Hitler had not named a Minister of Transport in his political will. Dorpmüller nevertheless belonged to the Reich government of Dönitz and the Schwerin von Krosigk cabinet as Reich Minister of Transport and Post.

Dorpmüller's reputation as an expert had not suffered among the Allies despite the war, and the Reichsbahn's involvement in the Holocaust was hardly discussed at the time. Dorpmüller was regarded as a non-political expert, not personally connected with the crimes of the Third Reich, to whom the former Chancellor of the Reich, Brüning, attested in a paper for the Allies that he had "resisted with great skill the pressure from the Nazis to promote prominent party comrades". General Carl R. Gray, a former railroad manager in charge of transportation for the U.S. Army who knew Dorpmüller from before the war, specifically suggested Julius Dorpmüller to the then General of the Army and military governor of the U.S. occupation zone in Germany, Dwight D. Eisenhower, for "reinstatement to the old office" because he had been "neither a Hitlerian nor a Nazi, as confirmed by our intelligence." The British also viewed Dorpmüller comparatively favorably. In Malente, Dorpmüller conducted initial negotiations with the Allies, including representatives of the Soviet Union. He considered it possible to get the German transport system back on track within six weeks, but demanded that he "not be interfered with", not even with regard to his choice of personnel. The Americans finally took Dorpmüller and his State Secretary Ganzenmüller and some of their staff by plane to Le Chesnay near Paris on May 23, 1945, making them the only members of the Dönitz government to escape arrest on the same day. At Le Chesnay, Dorpmüller was interned and interrogated along with other German business leaders such as Hjalmar Schacht, Albert Speer, and Ernst Heinkel. Among other things, he drew up a list of what he considered suitable candidates for posts in a future German transport administration. General Gray finally gave him the task of rebuilding the Reichsbahn administration of the US zone in Frankfurt am Main. To what extent this actually involved a comprehensive mandate to rebuild the German railroad system is unclear. However, the Western Allies repeatedly referred to his list in the period that followed when senior positions were to be filled at the Reichsbahn.

Dorpmüller returned to Malente from his stay in Le Chesnay on 13 June 1945 and began planning his move to Frankfurt. Due to advanced cancer, however, he had to undergo another operation on 23 June 1945. He did not recover from this operation, although he continued to hold meetings until shortly before his death. Julius Dorpmüller died on July 5, 1945 and was buried in the cemetery of Malente.

Transport of Soviet prisoners of war in open freight cars

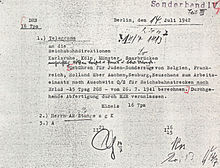

Reichsbahn telegram of 14 July 1942 concerning charges for "Juden-Sonderzüge" to Auschwitz

Destroyed locomotives of the Reichsbahn in Dresden, on one tender the slogan "Wheels must roll for victory".

French forced laborers in the construction of wartime class 52 locomotives

Julius Dorpmüller on a visit to the Generalgouvernement in 1942, here with the Deputy Governor General, Josef Bühler.

Electric locomotive E 19 in the Nuremberg Museum of Transport with swastika eagle (replica)

Minister of Transport Dorpmüller with Rudolf Jordan and Rudolf Heß at the inauguration of the Mittelland Canal (1938)

Delivery of the 05 001 express locomotive at Borsig in March 1935

First test drive of the "Flying Hamburger

Construction site of the Reichsautobahn near Berlin around 1936

Dorpmüller with Lammers and Hitler on 4 February 1937 on the balcony of the Reich Chancellery at a rally after his appointment as Reich Minister of Transport on 2 February 1937

Dorpmüller in the audience at a speech by Reich Minister of Transport and Post Paul von Eltz-Rübenach around 1935/36

Julius Dorpmüller (1932)

The Rail Zeppelin

Announcement of the appointment of Dorpmüller as President of the Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft

Opening of the Hindenburg Dam in 1927

After death

Postwar

In the post-war period, the Allies' interest in Dorpmüller as an expert in the reconstruction of the Reichsbahn served many of his former employees as a "clean bill of health" for Dorpmüller and the Reichsbahn as a whole. In an obituary as late as August 1945, the British Railway Gazette had praised him as "one of the greatest phenomena in modern transport", thus in a way anticipating the tenor of the post-war years. Accordingly, the late Reichsbahn Director General was seen and appreciated above all in his role as a non-political expert and successful railwayman. This was helped by the fact that, according to a letter dated 18 October 1949 from the Denazification Main Committee for Lübeck to his sister, Dorpmüller was classified as a "discharged person" in category V. This subsequent denazification had been initiated by the family for reasons of inheritance.

The newly founded Deutsche Bundesbahn, where many former employees of the Reichsbahn General Director held high positions, very soon made efforts to ensure Dorpmüller's posthumous fame. The Federal Railway Directorate in Hamburg took over responsibility for the care of his grave in Malente, and representatives of the Federal Railway regularly took part in memorial services and wreath-laying ceremonies. Publications of the Bundesbahn paid tribute to Dorpmüller, for example on his 100th birthday in 1969, when Heinz Maria Oeftering, the First President of the Bundesbahn, called Dorpmüller a "great railwayman" and a "role model for his own actions" in the company magazine Die Bundesbahn. Until 1985, there were busts of Dorpmüller in the stairwell of the Nuremberg Transport Museum, which was maintained by the Bundesbahn, and in the "Dorpmüller Hall" of Hanover's main railway station, which were removed during preparations for the celebrations of the 150th anniversary of the railways in Germany. One of these bronze busts, made for his 70th birthday, is owned by his Corps Delta in Aachen. There was also a "Dorpmüller Room" at the Federal Railway Head Office in Essen, which was also renamed the "Small Meeting Room" in 1985. The bust that was placed there has disappeared.

There were streets and roads named after Dorpmüller in Wuppertal, Magdeburg, Malente, Mayen, Hameln and Buchholz in der Nordheide, among others. While Dorpmüllerstraße in Wuppertal, for example, where his birthplace was located, had already been named after him before the war, other streets were only named after Dorpmüller in the post-war period, most recently in Buchholz in 1962. The Federal Railway maintained a training facility for its employees there until about 1980 under the name "Julius Dorpmüller School". With the increasing interest in the role of the Reichsbahn in the Holocaust, most Dorpmüller streets were renamed in the run-up to the 150th anniversary of the German railway from the mid-1980s. In Malente and Minden the street name existed until 1995 and 1996.

The maintenance of Dorpmüller's gravesite was discontinued by the Deutsche Bundesbahn on 31 December 1991 on the instructions of the Chairman of the Board Heinz Dürr. It was later taken over by a private individual.

Historiographical reception

The study of the role of the Reichsbahn and its chief Dorpmüller were neglected by West German and Western historians in the first decades after the war. Many works on the history of the Reichsbahn during the war were written at that time by former Reichsbahn employees and were limited to the appreciation of the performance of duty and work of the railwaymen and the top management of the Reichsbahn, e.g. the works by Pischel and Kreidler. Dorpmüller was praised in them as an undisputed and competent expert who had managed to protect the Reichsbahn from the party. The role of the Reichsbahn as a central instrument of warfare as well as its role in the transport of Jews was often simply not mentioned or the responsibility was assigned solely to State Secretary Ganzenmüller. A study on the history of the railways between 1941 and 1945, published by Hugo Strößenreuther on behalf of the German Federal Railways, also barely mentioned deportations. Some works, even of more recent times, show a decidedly hagiographic tendency, especially with regard to the person of the Reichsbahn General Director and Reich Minister of Transport. In the GDR, the reappraisal in the first decades after 1945 was limited to the emphasis on the anti-fascist resistance of railway workers and the portrayal of Dorpmüller as an "arch-Nazi".

It was only Raul Hilberg, with his study on the essential role of the Reichsbahn in the Holocaust, which was also published in German in 1981, who managed to draw a little more attention to the people of the Reichsbahn and the RVM who were acting at the time. In 1985 Heiner Lichtenstein published another work based on the files of the Ganzenmüller trial, which aroused renewed interest in the role of the Reichsbahn and its management personnel during the Holocaust and was the trigger for a more intensive debate about the RVM officials in the first place. A widely acclaimed exhibition in 1995 at the Berlin Museum of Transport and Technology under the title "Ich diente nur der Technik" (I served only technology) illuminated the career of Julius Dorpmüller together with that of other engineers and technicians who held high positions in the Third Reich, such as Heinrich Nordhoff and Wernher von Braun. In addition to the works of Hilberg and Lichtenstein, the studies of Alfred Gottwaldt and the American historian Alfred C. Mierzejewski, which deal with the role of the Reichsbahn and its leading personnel, are particularly noteworthy. The most comprehensive and scholarly work on Dorpmüller to date has been presented by Alfred Gottwaldt, although even this work is not a comprehensive biography, according to the author's own claim, but a "biographical sketch".

Julius Dorpmüller, according to Gottwaldt and Mierzejewski, was an excellent technician and good organiser, but not the strong leader and "Hindenburg of the Reichsbahn" that he was often portrayed as during the Third Reich and the post-war period. Having grown up politically in the time of the Kaiserreich and being rather nationally conservative, he was not a National Socialist, but made himself available to the aims and wishes of Hitler and his henchmen without hesitation, as long as he retained sole sovereignty and leadership of the Reichsbahn. His ambition was above all to secure the operation of the Reichsbahn and to defend its position at all costs. In judging financial and economic matters, he was ultimately dependent on his staff. He saw himself more traditionally as the supreme Reichsbahner, who viewed the railwaymen under his command in a caring and paternalistic manner. As "the Devil's General Director", as he was referred to in one publication, what distinguishes him from the model for this designation, General Harras from Carl Zuckmayer's drama Des Teufels General (The Devil's General), is that no self-doubt has come to light from Dorpmüller about his role and function in the Third Reich.

There has been and continues to be criticism of the increasing emphasis on the role of Dorpmüller and the Reichsbahn in the war and the Holocaust. In particular, the work by Bock and Garrecht, published in 1996, vehemently defended Dorpmüller and emphasized his sense of duty and the international recognition of the railway expert. In this perspective, partly characterized by "detached apologetics", which had already been taken by former Reichsbahn members since the 1950s, Dorpmüller and the Reichsbahn are judged above all as "abused by Hitler". His party membership was repeatedly negated until the 1990s.

It is uncertain to what extent Dorpmüller was concerned or even interested in the fate of the Jews transported to their deaths by the Reichsbahn and other victims of the persecution machinery of the Third Reich, just as there are hardly any other personal views and expressions of opinion known from him outside official announcements and publications, especially from the war years. Although, according to Gottwaldt's assessment, he was probably not an anti-Semite and repeatedly spoke up for former Jewish employees and other people who had come into conflict with the National Socialists, no statements beyond this are known. Dorpmüller's publications and appeals demanded obedience to Hitler from Reichsbahn employees until the last days of the war; their choice of words did not differ significantly from comparable appeals by party bigwigs. In view of his age, his resignation would probably have been granted without further ado, but instead he remained in office until the end, as far as his health permitted. Klaus Hildebrand concedes that Dorpmüller had little room for manoeuvre within his office, but criticises him for not making use of his remaining option to resign. His almost unbroken career from the Empire through the Weimar Republic stands for many comparable careers, but it is striking how much Dorpmüller knew how to come to terms with both the democratic governments of the Weimar Republic and Hitler's dictatorship, in this continuity perhaps still to be compared with Otto Meissner.

With his career, Julius Dorpmüller stands as a prototype for many technicians and engineers in the Third Reich who, disregarding moral concerns, saw it as their duty to implement their professional skills under all circumstances. This sense of duty, especially among members of technical disciplines - the historian Christopher Kopper describes it as a "narrowed sense of responsibility" using the example of Dorpmüller and leading Reich railwaymen - and its consequences have only been recognized as an area of research in historiography at a late stage. There is also still a lack of willingness in many disciplines to come to terms with their own history, Dorpmüller and transport being exemplary here too. "One went along with everything and was sometimes inwardly against it," concludes Gottwaldt.

Search within the encyclopedia