Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres [ɛ̃ːgʀ] (b. 29 August 1780 in Montauban; † 14 January 1867 in Paris) was a French painter and one of the most important exponents of official art in 19th-century France.

Ingres studied under Jacques-Louis David and at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He won the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1801 with the painting Achilles Receives the Petition of Agamemnon, but was subsequently unable to build on this success. In 1806 he took up the Rome fellowship that came with the prize and remained in Italy after it ended. His works from this period often met with harsh criticism. It was not until 1824 that Ingres returned to France as a result of his success at the Salon de Paris and became the recognized artist of his time. In 1825 the King awarded him the Cross of the Legion of Honor, and in 1829 he was appointed professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. After a failure at the Salon of 1834, Ingres decided not to exhibit there in the future and returned to Rome in 1835 as director of the Académie de France à Rome. After his tenure there ended, he returned in 1841 to continue teaching at the École des Beaux-Arts, and ten years later he was given the post of director there. In the last years of his life, Ingres placed particular emphasis on his body of artistic work and on consolidating his fame. In 1851, he began to establish the Musée Ingres in his hometown with donations dedicated to him, to which he also bequeathed many paintings and drawings of himself and with a connection to him in his estate.

Ingres was a representative of classicism and was in strong competition above all with Eugène Delacroix as a painter of French romanticism. In the opposite position to the painting style represented by Delacroix, Ingres was celebrated as a preserver of tradition. However, his works also showed foreshadowing of modernism. Thus, he often subordinated the representation of reality to his own imagination, which often led to inaccuracies in perspective and anatomically impossible representations. These subjective influences in the work were interpreted by critics as Ingres' inability. Ingres produced history paintings, portraits and nudes, for which he usually made a large number of preparatory drawings. In addition, there are still independent drawings. He himself regarded his histories as the most important group in his oeuvre, to which he could not devote as much time as he wanted, especially in his early years, due to the necessity of earning a living. In addition, he was a portrait painter in great demand, painting many important personalities of his time. Among his most important and best-known works are The Turkish Bath, The Great Bather, Napoleon I on his Imperial Throne, The Apotheosis of Homer, and Antiochus and Stratonice. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres exerted a great influence on the artists of his time and subsequent generations of artists. His works were received by Pablo Picasso, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Cindy Sherman, among others.

Self-portrait, 1804, Musée Condé, Chantilly

Signature of the artist

Live

Childhood and education

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was born on 29 August 1780 in the southern French town of Montauban, the eldest of seven siblings. His father Jean-Marie-Joseph Ingres (1754-1814) was a painter, sculptor, miniaturist, architect and plasterer and also became a member of the Toulouse Académie Royale de Peinture, Sculpture et Architecture in 1790. Even though the surviving works of Jean-Marie-Joseph Ingres are rather conventional and he was only of regional importance, Jean-Auguste-Dominique judged his father extremely positively and attested to him in later years that, had he had the opportunities he offered his son, he could have become the most important artist of his time in France. Ingres painted his first portraits of family members in his father's workshop at the age of ten, copied old paintings, reproductions of which hung in the house, and drew from plaster casts of antique sculptures. Already at this time he became acquainted with the tradition of profile portraits by Charles-Nicolas Cochin (1715-1790) and the physionotrace, a forerunner of photography, and thus came into contact with the problem of image and reality early in his life. In addition to his training as a draughtsman and painter, Ingres also received music lessons from his father and thus learned to play the violin. In addition to his son's training as a painter, his father also initiated his son's further artistic training. Thus, in 1791, at the age of eleven, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres began his studies at the art academy in Toulouse, of which his father was a member. His teachers there were the painter Joseph Roques (1757-1847), the landscape painter Jean Briant (1760-1799) and the sculptor Jean-Pierre Vigan (1754-1829). Only a few works have survived from his student days in Toulouse, which show his preoccupation with the pictorial works of antiquity, which was common at that time. He also won several academic prizes, such as the premier prix de composition in 1795 and the grand prix de peinture in 1796.

Despite the successful start to his training, the decisive step for the young artist was the move to Paris. In August 1797, Ingres began his studies with the classicist painter Jacques-Louis David in his studio in the Louvre, which was the most important training center for young artists in France during the Revolutionary and Imperial periods. There Ingres quickly gained the attention of his fellow students and his teacher. After merely copying in his father's workshop and at the Toulouse Academy, Ingres now devoted himself to preparing for the competitions of the École des Beaux-Arts, to which he was admitted in October 1799. His first surviving nudes and history paintings date from this period. In the following two years he successfully participated in the Prix de Rome of the École des Beaux-Arts. In 1800 he achieved second place, and in 1801 he won with his history painting Achill Receives the Petition Landscape of Agamemnon and received the Rome scholarship that went with it.

Beginning of professional life

In 1803 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres received his first government commission. He produced the portrait of Bonaparte as First Consul for the city of Liège. Ingres began work on the painting Napoleon I on his Imperial Throne in 1805, with which he first participated in the Paris Salon of the Académie des Beaux-Arts the following year. The painting met with considerable criticism because its style ran counter to contemporary taste. In October 1806, Ingres began his fellowship in Rome at the French Academy in the Villa Medici. The following year he broke off his engagement to Julie Forestier and did not return to Paris as planned. In 1808 he showed his new paintings The Great Bather and Oedipus and the Sphinx at the Académie de France exhibition and received poor reviews for them.

When Ingres' scholarship ended in 1810, he decided to stay longer in Italy. He moved to the Via Gregoriana in Rome and met, among others, the painter Charles Marcotte. In 1813 Jean-Dominique Ingres married Madeleine Chapelle in Rome, whom he had previously only met by letter. Also in this year he painted his first version of Raphael and the Fornarina, a motif to which he was to devote himself again and again. In 1814, the year of his father's death, Ingres traveled to Naples. There he painted portraits of Caroline Murat, Napoleon's younger sister and Queen of Naples, and other members of the royal family. The following year he was again struck by fate when the child of the Ingres couple died in childbirth. The couple subsequently remained childless. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres' mother died in 1817, and in that year he received two commissions for paintings from the French ambassador in Rome. These were Christ Handing the Keys of Paradise to Peter and Roger Freeing Angelica. In 1819 Ingres again exhibited several paintings at the Salon de Paris and again received negative reviews.

In 1820 Ingres and his wife moved to Florence. First he moved in with his childhood friend Lorenzo Bartolini, then he moved into his own apartment. There Ingres copied paintings by other artists in the Palazzo Pitti and the Uffizi, among other places. In 1822 and 1823 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres struggled with his artistic situation, as he spent most of his time on portrait commissions, although he would have preferred to devote more time to history painting. In 1824, several months late, he showed the painting The Vow of Louis XIII at the annual Salon. There it met with such a positive response that Ingres decided to return to Paris.

Return to France and start of teaching

As a result of the Salon's success, Ingres received a commission from the Minister of the Interior in 1824 for the monumental painting The Martyrdom of Saint Symphorian in Autun Cathedral. After the Salon ended, the French King Charles X awarded Ingres the Cross of the Legion of Honour in 1825. The artist described this day as the happiest of his life. The following year, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres opened an art school near his studio. This was the beginning of his career as a teacher. In December 1829 he was appointed professor of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, taking up the post on 1 April 1830. Three years later he was appointed director of the institute. At the Salon of that year he showed the portrait of Louis-Francois Bertin, which received good reviews.

Director in Rome, Rector in Paris

After his painting The Martyrdom of Saint Symphorian became a failure at the Salon in 1834, he decided never to exhibit there again. That year he applied for the post of director of the Académie de France in Rome. This application was successful, so that in 1835 he returned to Rome and took over the direction of the Academy. He worked very hard in his post there and resumed his own artistic activity. In 1840 Ingres did not publicly exhibit the painting Antiochus and Stratonike in the Appartement de Duc d'Orléans. On 31 May 1842 he was admitted to the Prussian Order pour le merite for science and the arts as a foreign member.

At the end of his six-year term, Ingres returned to Paris, where he received a professorship at the École des Beaux-Arts. Ingres spent the summer of 1843 with his wife at the Chateau de Dampierre. There he began work on the mural The Golden Age.

On 27 July 1849 Madeleine Ingres died of a blood disease.

In October 1851, instead of his professorship, he received the title of rector, which came with a lifetime salary. Subsequently, Ingres devoted himself increasingly to projects with which he wanted to ensure his posthumous fame. As early as the summer of 1851, he had begun to lay the foundations for a museum in his hometown of Montauban by donating part of his collection to the city. In addition, Ingres drew up a large résumé of his previous work for the first time in this year. An edition of his works was published by Achille Réveil and Albert Magimel (1799-1877), which included more than 100 reproduction engravings. Ingres often intervened in their design himself and altered early works, for example, which he then nevertheless had published as authentic.

On April 15, 1852, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres married his second wife, Delphine Ramel, who was 30 years his junior.

In 1854, the Musée Ingres moved into a room in Montauban's town hall, which represented a special tribute to the artist by his hometown. At the 1855 World's Fair in Paris, Ingres showed a comprehensive retrospective of his work with a total of 69 paintings and was thus in the special focus of public attention alongside Eugène Delacroix, who also showed a retrospective on this occasion. In 1858 Ingres produced a self-portrait for the gallery of self-portraits in the Florentine Uffizi. In doing so, he joined a line of great artistic personalities, not portraying himself as a painter, but staging an image of himself as a representative of the bourgeoisie. The following year, Ingres sold the first version of the painting The Turkish Bath to Prince Napoleon, who, however, soon had it returned to the artist, who then revised it again. In 1861, an exhibition of over 100 drawings was dedicated to Ingres by the Société des Arts-Unis in Paris, and the following year he was appointed by Napoleon III as a member of the Senate.

On 14 January 1867, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres died in his Paris apartment. He was buried in the Père Lachaise cemetery. In his will, he bequeathed over 50 paintings by himself and other artists, paintings by his students, thousands of drawings, as well as works of early Italian painting and antique vases to his hometown for the Musée Ingres.

Portrait of Julie Forestier by Ingres

_-_Zelfportret_(1864)_-_28-02-2010_13-37-05.jpg)

Self Portrait (1864)

His tomb at the Père Lachaise cemetery

Works

History painting

In 1854, Ingres exhibited the painting Joan of Arc at the Coronation of Charles VII in Reims Cathedral. It is one of the paintings in which he linked religion and politics. The painter chose the presence of Joan of Arc at the coronation of Charles VII on 17 July 1429 as his motif. In doing so, he did not refer to the dramatic aspects of her story, such as her death at the stake or the siege of Orléans, as many of the Joan of Arc paintings of the 19th century did. Joan of Arc stands sideways at the altar of Reims Cathedral. With her right hand raised, she holds a flagpole of striking red color, her left hand resting on the altar. This pose, together with the upward gaze, indicates her religious visions and thus her mediating role between heaven and earth. Ingres provided Joan of Arc with a halo, thus underlining her claim to canonization, which was not undertaken by the Catholic Church until 1920. The freedom fighter was depicted by Ingres in her armour, which reinforces the static impression of the picture and also emphasises her body. Ingres allows a subtle eroticism to be expressed in the painting, in that the epaulettes of the breastplate suggest breasts and the skirt covering half of the armour exposes her right leg to view, which is also emphasised by the red flagpole. The painting Joan of Arc at the Coronation of Charles VII in Reims Cathedral, however, contains a personal level of interpretation beyond the historical event. Inges chose his wife Delphine, whom he had married during the painting's creation, as the model for Joan of Arc; he depicted himself as a knight on the left edge of the picture. Both wear armour and are positioned in the light. The unifying element in the composition is a dark canopy, in front of which only their two heads can be seen. This painting is thus also an example of how the pictures painted by Ingres increasingly became a personal confession from the middle of the 19th century onwards.

Portraits

Ingres was a very popular portrait painter in his time, but turned to this genre only out of necessity to finance his life, although history painting, which was at the top of the genre structure, interested him more. In the middle of the 19th century, when he was a recognized artist in Paris, he received portrait commissions from many influential and important personalities. At the same time, his portraits, in which he sometimes depicted space and bodies in a manner alien to reality, were not without controversy. Art critics, for example, interpreted arms that were longer than would have been the case in an anatomically correct representation as insufficient skill on Ingres' part. The latter, however, did not attempt to represent reality, but showed his own adaptations of the subject of the picture. Characteristic for the portraits of Ingres is the accuracy of the representation of clothing and accessories and the great importance they take in the picture.

One example of Ingres' early portraits of rulers is Napoleon I on his imperial throne from 1806. He had already produced the portrait of Bonaparte as first consul in 1804. After his coronation as emperor in December 1804, Jacques-Louis David and two of his pupils, but not including Ingres, were commissioned to produce a life-size portrait. Ingres worked on this painting without a commission, probably hoping for success with this subject in his first participation at the Salon. The painter showed Napoleon in coronation regalia with some symbols and attributes of power. The emperor is seated frontally on a throne, his head is in the centre of several circles formed by the throne and clothing, reminiscent of a halo. In the depiction, the emperor becomes a kind of religious icon. The polished ivory globe, symbolizing a globe, on the back of the throne decorated with an eagle has a reflection of the window. The motif of the eagle is repeated in the carpet at Napoleon's feet and refers as a symbol to Jupiter, the father of the gods. Ingres attached particular importance to the depiction of the insignia of power, the sceptre, the hand of justice, the cross of the Legion of Honour and Charlemagne's sword, so that the person of the emperor recedes behind them. The rigid posture and gaze as well as the stone-grey colour of the skin also make the depiction lie somewhere between a moving body and a stone statue. The painter was inspired by images of Roman, Byzantine and medieval rulers, thus distancing himself from the reality of the Napoleonic period. This led to strong opposition from art critics, who accused Ingres of an archaic and Gothic style and criticized the content of the painting. This verdict had already been reached at a preview for the Salon, where criticisms included the portrait's dissimilarity to Napoleon and its reference to Charlemagne, who was no longer desirable in post-revolutionary France. However, the painting must also have met with a positive response, as it was acquired by the Corps Législatif, the legislative assembly.

Even the portrait of Bonaparte as first consul was in the service of propaganda for Napoleon. The commissioned work sets the scene of a benefactor posing in front of a window with a view of the Lambertus Cathedral. The autocrat, already 34 years old, is depicted as highly present, youthful, fresh, pleasant, downright amiable, friendly and sympathetic. The church is depicted as intact, although it has been continually destroyed since the French Revolution. Napoleon never intervened against the sacrilege of the church, even later. The painter imagines the repair of the church building. Part of the staging - Napoleon as peacemaker - was Napoleon's visit in 1803 to the city, which was still scarred by the Revolutionary War. In addition, Napoleon paid 300,000 francs to rebuild the demolished Amercoeur quarter. Depicted in the oil painting is a deed of gift to which the ostensible benefactor points his finger. The city additionally received the painting. In the neighbouring country, which had only been annexed for a few years, the French dictator was to have a prescribed pictorial presence. The "master of the material" shows the first consul wrapped in ostentatious clothes as if on a stage, lets him step out plastically almost from the painting and illustrates his unique ability to enhance the models he painted. It was his first and at the same time only equally pleasing depiction of the later emperor.

One of the portraits in which Ingres put his artistic freedom above correct representation is the portrait of Madame Marie-Genevieve-Marguerite de Senonnes from 1814. The young noblewoman was painted by Ingres in a red dress in front of golden cushions. Thus, two warm colours dominate, creating a familiar atmosphere. Behind her on the wall is a mirror in which the viewer can see the sitter's back and the back of her head. The mirror is an element that Ingres used in several portraits to render a second view of the person and the room. The many jewels worn by Marie-Genevieve-Marguerite de Senonnes are also striking. Madame's right arm, which is anatomically much too long, does not immediately catch the viewer's eye. Here Ingres abandoned the representation of reality in favour of a more pronounced roundness. This circumstance can also be demonstrated in other portraits.

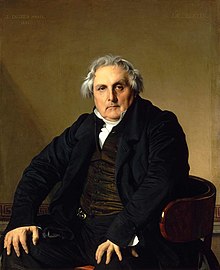

The portrait of Louis-François Bertin, painted by Ingres in 1832, is one of his most successful works in this genre. With it, he was successfully represented at the Salon of that year. Louis-François Bertin (1766-1841) was an important publisher and representative of the increasingly self-confident middle classes. In the painting, Ingres emphasizes the hands, which he once again did not depict according to anatomical standards, and Bertin's head as the seat of intelligence and his drive. Behind them, fashion and the man's appearance take a back seat, expressed in the dishevelled hair and rumpled shirt. The publisher is depicted seated on a chair with a round back and close to the picture plane. The position of his supported hands suggests that he is about to stand up. There are several distortions in the image. The gesture of the propped-up arms lacks perspective and thus violates the ideals of academic painting. Bertin's right hand also appears more like a paw, while the fingers of the left are twisted so that the thumb slips into an out-of-place position. There is also a spatial distortion in the oversized seat of the chair. These violations of reality serve solely to underscore Bertin's mass and impact. Another detail in the portrait is the reflection of the window on the back of the chair and Bertin's glasses. In this way, Ingres quotes his model Raphael on the one hand, but also draws on 15th-century Dutch painting. This portrait met with an extremely positive response. Charles Baudelaire called it attractive, others recognized in it Bertin as a bourgeois Caesar, who as a character characterized the entire epoch.

·

"Bonaparte, Premier Consul" (1804, Grand Curtius, Liège) - in the background an intact cathedral, which, however, had already been largely destroyed

·

Portrait of Madame Riviere. 1806. oil/linen.

·

Portrait of Princess Albert de Broglie. 1853. oil/linen. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

·

Portrait of Baroness James de Rothschild. 1848. oil/linen. 142 × 101 cm. Private collection

·

Madame Paul-Sigisbert Moitessier, née Marie-Clotilde-Inès de Foucauld. 1856, oil/linen. 120 × 92 cm, National Gallery, London

File

Ingres dealt with the depiction of bathers and bathing scenes several times in the course of his career. Thus, Ingres painted The Large Bather in 1808 and The Small Bather in 1828. Ingres took up this theme again in his late work The Turkish Bath from 1863, which is one of his most famous works. It was produced in two versions. He completed the first in 1859 and sent it to Prince Napoleon, who had commissioned the painting. However, after a short time in the prince's possession, he sent the painting back, presumably at the instigation of his wife. Ingres then reworked the originally rectangular picture into a tondo and also changed some details in the picture. In this painting, the painter on the one hand combines figures from his earlier works and now places them in a new context in terms of content, and on the other hand he draws on figures from books and engravings. In the foreground, for example, is the back view of The Great Bathing Woman, who is now making music and is also set apart from the other, paler women by the lively, warm hue of her body. The picture The Turkish Bath is a multi-figure composition that appears static and does not depict any action. The individual figures and groups of figures have no connection to each other, but exist side by side.

·

The Great Odalisque. 1814. 91 × 162 cm. Louvre, Paris

·

Odalisque and slave girl. 1842. oil/linen. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

·

The spring. 1856. oil/linen. 163 × 80 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Drawings

Ingres' works remained little noticed for a long time. While the earlier ones are entirely in the pseudo-classical direction of David, his two later major works, the "Oath of Louis XIII" and "the Apotheosis of Homer", are painted entirely after Raphael. In his last period Ingres turned again to the antique direction, and in particular his "Stratonike" appears as an imitation of antique genre painting, the figures being reminiscent of the Etruscan vase paintings, and all the accessories being executed with minute accuracy.

Ingres attached more importance to drawing and modelling than to colour. It is not surprising, then, that during the lifetime of the two school leaders and their followers, there were sharp contrasts and massive antagonisms between the Ingristes or Dessinateurs and the Coloristes, Delacroix's pupils and admirers. By emphasizing the graphic at the expense of color, Ingres's pictures acquire something dry and cool; nor was he an innovator and inventor. On the other hand, his careful studies, the purity and precision of his lines and outlines deserve the greatest recognition: Ingres, as well as some of his students, achieved outstanding work in this serious, strict direction. This is confirmed by an original drawing by Ingres' hand, "The Farnese Bull" (Naples 1814), which appeared in the art trade in 1981.

Théodore Richomme, Luigi Calamatta and Louis Pierre Henriquel-Dupont produced excellent copper engravings after his works. They were also published in outline by Achille Réveil (Paris 1851).

·

The Harvey sisters. 1804.

·

Charles Robert Cockerell. c. 1813.

·

The Montagu sisters. 1815.

·

The Stamaty family. 1818.

·

François Pouqueville. 1834.

·

The wife of Victor Baltard (née Adeline Lequeu) and her daughter Paule. Gift from Ingres with dedication, Rome 1836.

·

Portrait of Guillaume Guillon-Lethière.

The Bathers of Valpinçon , 1808, Louvre, Paris

The Turkish bath , 1863

Louis-François Bertin , 1832

Joan of Arc at the coronation of Charles VII in Reims Cathedral , 1854

Napoleon I on his imperial throne , 1806

Search within the encyclopedia