Jaundice

Icterus (formerly and Latin Icterus; from ancient Greek ἴκτερος, íkteros, "jaundice"), also called jaundice (from Middle High German gëlsuht; obsolete also Gallsucht), is a yellowing of the skin, mucous membranes as well as the sclera of the eyes due to an increased concentration of bilirubin in the blood. It is a symptom already described in ancient times in the Near East, which can occur in various diseases.

In linguistic usage, jaundice and liver inflammation are often equated ("jaundice epidemic" in the case of frequent hepatitis cases in the 1960s and 1970s). Today, jaundice no longer denotes a disease, but rather a symptom that can occur in many diseases, including hepatitis (for example, viral hepatitis, the sporadic form of which was formerly called icterus simplex or icterus catarrhalis) and diseases of the bile ducts.

Icterus is caused by a disorder in the bilirubin metabolism. Bilirubin is a breakdown product of the red blood pigment haemoglobin. Increased accumulation or reduced excretion of bilirubin initially leads to an increase in serum concentration (hyperbilirubinemia) and then to leakage through the vascular endothelium with storage in the body tissue.

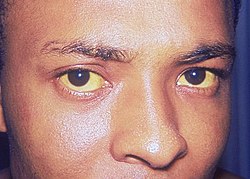

From a serum level of more than 35 μmol/l (= 2 mg/dl), the colour change first appears on the (otherwise white) sclera of the eye (scleral icterus). As the values increase, the yellowish changes can also be observed on the skin and mucous membranes. The body fluids and other organs are also affected. The urine may be dark brown (bilirubinuria), while the stool may be light or white in colour.

Since the liver plays a central role in the underlying bilirubin metabolism, the following causes of icterus can be distinguished, depending on the localization of the disorder:

- prehepatic (with cause "before the liver", usually associated with an increased attack of bilirubin due to hemolysis)

- intrahepatic (due to liver damage or liver dysfunction) and

- posthepatic (when the bile duct system downstream of the liver is disturbed; usually a disturbance of bile flow)

Furthermore, in about five percent of the population, bilirubin uptake into the liver is slightly chronically reduced due to a genetic defect. This disorder is known as Gilbert's syndrome. In these cases, mild forms of jaundice, particularly yellowing around the conjunctiva, occur regularly. This type of jaundice, if no other physical abnormalities are observed, is harmless and does not need to be treated.

Marked yellowing of the sclerae and facial skin, in this case caused by hepatitis A

Hemolytic icterus (prehepatic)

In prehepatic jaundice, the greatly increased decay of red blood cells (erythrocytes) in the context of hemolysis leads to an increased accumulation of unconjugated bilirubin. The same mechanism occurs physiologically in neonatal icterus (haemolytic neonatorum). Shortly after birth, the erythrocytes loaded with fetal hemoglobin are increasingly broken down and replaced by newly formed red blood cells. Neonatal icterus is a sign of this ongoing reaction and is usually harmless. In the case of massively elevated bilirubin levels shortly after birth (e.g. due to an existing rhesus incompatibility (erythroblastosis) or in premature births), however, there is a risk of kernicterus, damage to important centres of the central nervous system with a poor prognosis.

Prehepatic icterus can also occur in blood transfusion complications (loss of blood cells), as a result of a pulmonary infarction and in the case of large haematomas.

Hepatocellular jaundice (intrahepatic)

Since several steps of bilirubin metabolism take place in the liver, there are accordingly also different possibilities for the development of (intra)hepatic icterus. Essentially, the following processes can be disturbed:

- hepatocellular bilirubin uptake

- Bilirubin conjugation (conversion of water-insoluble, unconjugated bilirubin into water-soluble, conjugated bilirubin with the aid of glucuronic acid)

- Transport of conjugated bilirubin out of the liver cell

- Outflow from the bile ducts of the liver into the intrahepatic bile ducts

bilirubin imbalance

Insufficient uptake of unconjugated bilirubin may be due to liver cell damage, for example in the context of viral hepatitis or acute liver failure, or to an overload of the cell's own transport system. Some drugs (some antibiotics, for example) have to be excreted via the same transport pathways and may compete with bilirubin.

bilirubin conjugation disorder

It is usually triggered by genetic defects in the enzymes involved (especially UDP-glucuronyltransferase). The best-known diseases in this context are Gilbert-Meulengracht syndrome and Crigler-Najjar syndrome.

bilirubin imbalance

In addition to liver cell damage of various causes, hereditary disorders of the necessary structures can also be triggering. These include the Dubin-Johnson syndrome or the rotor syndrome. In the case of inanitional icterus, mobilized fatty acids displace bilirubin from the transport proteins.

bile duct obstruction

Similar to posthepatic jaundice, several other substances are affected by the lack of excretion in addition to bilirubin. Therefore, we speak of an intrahepatic cholestasis.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is jaundice?

A: Jaundice is a medical condition where the skin and the whites of the eyes turn yellow.

Q: What causes jaundice?

A: Jaundice is caused by problems with the liver not being able to remove heme properly. Heme changes into a chemical called bilirubin after red blood cells die, and bilirubin causes the yellow coloration of the skin.

Q: When is jaundice common?

A: Jaundice is common in newly born babies, usually starting on the second day after birth.

Q: What other diseases can cause jaundice?

A: Other diseases that can cause jaundice include malaria, hepatitis, and gallstones.

Q: What is the most common liver problem?

A: Jaundice is the most common liver problem.

Q: What is bile?

A: Bile is a digestive fluid made by the liver that is necessary for proper nutrition, and it also prevents decaying changes in food.

Q: What happens if bile is unable to enter the intestines?

A: If bile is unable to enter the intestines, then there will be an increase in gases and other byproducts. Normally, the production of bile and its flow is constant.

Search within the encyclopedia