James Cook

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see James Cook (disambiguation).

![]()

Captain Cook is a redirect to this article. For other meanings, see Captain Cook (disambiguation).

James Cook (b. 27 Oct. Jul. / 7 Nov. 1728greg. at Marton near Middlesbrough; † 14 Feb. 1779 at Kealakekua Bay, Hawaiʻi) was a British navigator, cartographer and explorer. He became famous for three voyages to the Pacific Ocean, which he mapped more accurately than anyone before him. He discovered numerous islands and proved that the Terra Australis did not exist and that the Northwest Passage could not be traversed by ships of his time. Of great importance for seafaring were also his effective measures against scurvy.

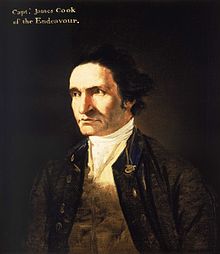

James Cook (Nathaniel Dance-Holland, 1776)

Live

Cook's birth is recorded in the parish register of St Cuthbert in Yorkshire with the entry "27 October 1728. James, son of James Cook, a day labourer, and his wife Grace". He was one of eight children. At the expense of his father's employer, Thomas Skottowe, he was able to attend the village school at Great Ayton. Here he acquired proficiency in reading, arithmetic and writing. At 17, at his father's request, he became an apprentice in the general store of the Quaker John Walker, who became a sort of mentor to him. Quaker contacts brought him into contact with seafaring, but he did not become a Quaker himself.

Seaman

His seafaring career began at the age of 18 on coal transport ships between Newcastle upon Tyne and London, based at Whitby. Cook's skills took him well. In mid 1754, at a financial loss, he transferred to the Royal Navy where he signed on as Able Seaman on HMS Eagle. Only service to the Crown afforded the prospect of considerable social advancement.

Naval Officer

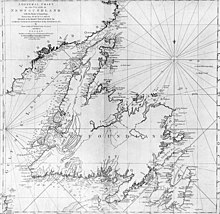

James Cook was given his first small command on 5 April 1756 and passed the Master's examination in 1757. Between 1755 and 1758 he had served as Master's Mate on HMS Eagle under Palliser. His superior talent as a cartographer was demonstrated from 1758 onwards when he explored and surveyed especially the St Lawrence River (in the run-up to the Siege of Quebec), waters of Newfoundland and other parts of the east coast of Canada during the Seven Years' War (1756-1763).

Cook's precise maps helped the British troops under General James Wolfe to a decisive victory over the French at Quebec in September 1759. From 1764 to the end of 1767, he had been given command of the small schooner Grenville for his surveying work through the agency of Palliser, by then appointed governor of Newfoundland, which he sailed several times and quickly across the Atlantic, proving his qualities as a seaman. During the winter period he was engaged by order of the Admiralty in England in the preparation of charts and sailing manuals from his summer measurement data. His reputation as a shipmaster and cartographer earned the seaman, who was appointed lieutenant on 25 May 1768, the appointment to the famous Pacific voyage, which was envied by some, for example by Alexander Dalrymple, later the first hydrographer of the Admiralty.

First voyage to the South Seas (1768-1771)

This expedition was undertaken on the recommendation of the Royal Society under the presidency of the astronomer Lord Morton in order to observe the passage of the planet Venus in front of the solar disk - the Venus transit of 3 June 1769 - on Tahiti as part of an international measurement campaign. The aim of this major astronomical project was to determine the distance between the Earth and the Sun and thus - on the basis of Kepler's third law - to calculate the distances of all the other planets in the solar system.

Cook's main task was to get several scientists (including astronomer Charles Green) and their instruments safely to Tahiti and back. He needed a spacious ship with a shallow draft for this purpose. The Admiralty acquired the 340-ton coal carrier Earl of Pembroke, which was converted and named HMSEndeavour. The ship set sail on 26 August 1768.

In addition, James Cook received a secret order - which he was only allowed to open after the first part of his voyage (the observation of the passage of Venus) had been fulfilled - to explore the ocean south of the 40th parallel south and to find a huge "southern continent" (or the "Great Southern Land", the Terra Australis incognita) postulated by cartographers, which was thought to exist as a counterweight to the land masses of the northern hemisphere. Moreover, the existence of Torres Strait near New Guinea, kept secret by Spain, was known to the Admiralty, but had not yet been confirmed by any of its ships.

At his own expense (to a similar amount as the Crown invested in the expedition), the 25-year-old naturalist Joseph Banks also took part in this expedition, primarily to make botanical collections. He had organized a staff of ten for this purpose, including the 39-year-old Swedish botanist Daniel Solander, like Banks a member of the Royal Society. After a three-week stopover in Rio de Janeiro, where the ship was thoroughly overhauled, Cook set sail again in early December and arrived in the Bay of Good Success at Le Maire Strait (Tierra del Fuego) in early January 1769.

By the end of January, HMS Endeavour had rounded Cape Horn with luck and was at latitude 60, the southernmost point of this voyage. By mid-April Tahiti had been reached, HMS Endeavour was berthed in Matavai Bay, and work began on setting up Fort Venus. At the beginning of May, the observatory was also ready for use and the exploration of Tahiti was started.

After the successful observations (at the last moment Cook had to recover a stolen instrument) he left Tahiti in mid-July together with Tupaia, his native guide. He cruised between Tetiaroa, Moorea, Huahine, Bora Bora, Raiatea and left the Society Islands in mid-August heading south. In early October, he sighted New Zealand - in search of a land that the Dutchman Abel Tasman had marked on a nautical chart over a hundred years earlier with little more than a few pen strokes. Cook spent six months mapping the country in detail and discovered the Cook Strait, thus proving New Zealand to be a double island.

On April 28, 1770, the crew of HMS Endeavour became the first Europeans to set foot on the east coast of New Holland, as Australia was then called after its discoverers. They named the place Botany Bay because of the very numerous new plants they found. Eight days later, they sailed 3,200 km northward along the coastline and continued to gather cartographic information. On June 11, HMS Endeavour ran aground at Cape Tribulation on Endeavour Reef, located in the Great Barrier Reef, and was nearly lost. While the ship's carpenters were repairing the ship, which took a total of six weeks, Banks observed "huge hares," which the natives called kangaroos. Cook then continued on, finding Cook Passage through the Great Barrier Reef in mid-August, and was finally free to sail north.

A week later he landed again and named the country New South Wales, before sailing westwards through Endeavour Strait (the southernmost part of Torres Strait) to find that New Holland and New Guinea were separated, whereupon he took possession of the east coast of New Holland for England. On October 10 he reached Batavia, then the Dutch Indies, where he had the ship thoroughly overhauled for three weeks. During this time seven of his men fell victim to diarrhoeal diseases, and many more, including the astronomer Green, died on the onward voyage before HMS Endeavour was able to make a month's stay at Cape Town from mid-March 1771, where she was again mended.

On July 13, 1771, Cook set foot on England's soil for the first time after a three-year expedition, and on the 16th HMS Endeavour tied up at Woolwich. On August 14, the First Lord of the Admiralty Earl of Sandwich presented him to King George III, who personally promoted him to Commander.

Second voyage to the South Seas (1772-1775)

Lacking "literary quality," Cook's notes were not published after his return. Instead, the version of the novelist and librettist John Hawkesworth was published, who used Cook's and Banks's diaries but introduced gross inaccuracies and simple-minded views. Alexander Dalrymple, who thought he had just logically proved the Terra Australis in a two-volume work, criticized Cook on the basis of Hawkesworth's publication and moved the southern continent postulated by him to areas "which Cook had insufficiently explored".

The Admiralty was not inconvenienced by the "scientific" demand for another expedition in view of the high-quality chart material supplied by Cook, and while Dalrymple continued to adhere to his criticism of Cook, two ships in mint condition were found, upgraded and renamed Resolution and Adventure. These were again freighters from Whitby. The ship of his first voyage, the Endeavour, on the other hand, was no longer serviceable.

Joseph Banks wanted to participate again, but demanded such extensive modifications for his working group and the intended collections that he was ultimately rejected after the reduced seaworthiness of the Resolution due to the raised superstructures came to light during a sea trial. In his place, the Prussian Johann Reinhold Forster and his son Georg accompanied the expedition for the collection of astronomical, natural history and geographical knowledge. In addition, the classicist painter William Hodges was with them, as well as two astronomers (one on each ship) who were responsible for keeping track of the new time keepers. Since Cook's measures against scurvy had been successful, experiments continued along this path: In addition to malt and sauerkraut, they now carried carrot jelly and beer condensate.

The voyage began at Plymouth on 13 July 1772. Cook set course for Cape Circoncision at about 54° south via Cape Town, where he stayed for three weeks from the end of October. This had been discovered thirty years earlier by Charles Bouvet, who had mistaken it for a promontory of Terra Australis.

Icebergs were first encountered at the 51st parallel. On January 3, 1773, one was about five degrees south of the mainland discovered by Bouvet. Since Cook did not get to see Bouvet Island, he assumed Bouvet had mistaken an iceberg for mainland. On 17 January, the expedition was the first to cross the southern Arctic Circle (66° 30' S), but then had to turn around at latitude 67° 15' S due to impenetrable ice and headed northeast again.

On 9 February, near the Kerguelen Islands, contact with HMS Adventure was lost in dense fog. As a rendezvous point in New Zealand had been arranged for such an eventuality, Cook continued after the Resolution had fired cannon shots unsuccessfully for an afternoon, and steered even further south. He reached 61° 52' S on 24 February, then had to keep northward, and on 27 March, after 117 days at sea, he hit the southern tip of New Zealand, where he allowed his men a fortnight in Dusky Sound and had the ship overhauled. He had zigzagged the area around 60 degrees latitude without encountering a continent. Dalrymple's view was thus disproved.

When Cook went to the rendezvous point in Queen Charlotte Sound on 18 May, where HMS Adventure had been waiting for six weeks, Cook had one serious and three mild cases of scurvy, while HMS Adventure had twenty serious cases. Her commander had not taken the dietary regulations too seriously. Goats that had been brought along were put out and potatoes and turnips were planted.

As the southern winter approached, Cook then moved towards the tropics. On 2 August he was close to the position of Pitcairns given by Carteret, but that was certainly not where the island lay. Twenty cases of scurvy had again appeared on HMS Adventure. Cook set course for Tahiti, where he arrived on 17 August.

He sailed on in early September and arrived at the Tonga Islands in early October, where he was very kindly entertained, prompting him to name them the Friendship Islands. As is now known, it was only by chance that his party was not massacred in the night after one of the friendly entertainments. The islanders did not carry out their plan only because of quarrels among themselves at the last moment.

He turned again towards New Zealand, which he sighted on 21 October. On 30 October he lost contact with HMS Adventure in heavy weather and continued along the coast. On 25 November he left a message for HMS Adventure in a bottle at the appointed place, stating his intended route. He then turned south and crossed the 67th parallel before ordering a course north again on 24 December 1773 because of the ice.

On 11 January 1774 he headed south again, to the dismay of the crew, who had already thought they were on their way home. On 30 January he reached the southernmost point of the voyage, 71° 10' S, 106° 54' W, and ended the advance in the knowledge that no major land could be there either. Only James Weddell was to come further south in 1823: at 74° 15' S.

Cook now ran northward, unsuccessfully searching for the Juan Fernández Archipelago, designated "continent" in 1563, and himself fell ill with biliousness. Forster agreed to have his favourite dog slaughtered and prepared to cure the captain - with success (23 February). Cook reached Easter Island on 11 March, noted there about the drinking water "so bad, hardly worth bringing aboard", and sailed through the Tuamotus and Melanesia again to Tahiti (22 April), the New Hebrides and New Zealand again, still discovering New Caledonia. Asked about HMS Adventure, the New Zealand Maori dodged the question. It later emerged that a landing craft carrying eleven men had been attacked, the men killed and possibly consumed. HMS Adventure had left New Zealand in late 1773 and arrived in England sailing around Cape Horn in July 1774. She had thus become the first to circumnavigate the globe on an easterly course.

The Resolution set sail on November 10, passed Cape Horn, searched the South Atlantic, and discovered for England the barren islands of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. From Cape Town, the Resolution set course for St. Helena and Ascension, searched for the imaginary "Matthew Island" marked on 15th century Portuguese maps, and was so close to Brazil that Cook decided to still determine the position of Fernando de Noronha. They returned to England via the Azores on 30 July 1775. Of the 112 crew, only four had died en route (two from accidents, one from alcohol poisoning, one suicide), none of them from scurvy.

Ethnological objects from the South Seas collected during the expedition were distributed among museums in Europe; a large part of them ended up in the Cook-Forster Collection of the Völkerkundliches Museum Göttingen.

Third voyage to the South Seas (1776-1779/1780) and death

After the second voyage Cook was famous, was promoted to the rank of post-captain, had a secure, well-paid post at Greenwich Hospital (home to indigent naval veterans) and had been appointed to the Royal Society in recognition of his measures against scurvy. "The Resolution is in excellent condition and will soon start on its next voyage - without me," he wrote to Whitby. The planned reason for the voyage was the Northwest Passage. Since cargoes from the Far East had increased greatly, a shorter and, in wartime, safer northern route was not just a topic of conversation. That the Dane Bering had already searched there in 1728 was known, although without details.

No one would have expected Cook to take on another such burden: he offered himself and could expect not to be refused. The model Polynesian Omai - who had come along on the second voyage from Huahine and had advanced to become the popular noble savage of London society - was to be brought back to his homeland on this third voyage by ship.

Important participants of the expedition were the painter John Webber and the later explorers George Vancouver and Heinrich Zimmermann. The latter published his travel memoirs - despite a ban by the British Admiralty - as "Heinrich Zimmermanns von Wissloch in der Pfalz, Reise um die Welt, mit Capitain Cook". James Cook's Sailing Master of the Resolution was William Bligh, later Captain of the Bounty Expedition.

Cook's voyages of discovery had also attracted international attention in the meantime. In 1776, the naval officers of France, Spain and the United States had been instructed by their respective governments to let Captain Cook off scot-free even if they were at war with England. Furthermore, he was to be treated with the utmost respect, as if he were a civilian, since ultimately all countries benefited from Cook's discoveries in the form of sea charts.

On 12 July, Cook set sail from Plymouth to sail first via Tenerife to Cape Town. There, the second ship, the HMS Discovery under Captain Charles Clerke, joined the expedition in November. Cook did his first survey work for about a week at the end of December on the Kerguelen Islands, which their discoverer in 1773 had also still considered to be part of the southern continent and had called France Australe. Cook called them Poverty Islands before turning towards New Zealand.

At the end of January he arrived at Adventure Bay, Tasmania, where contacts with the natives were interfered with by Omai, who misinterpreted their advances and fired his gun. After discovering some of the southern Cook Islands, the ships were in Queen Charlotte Sound in February, where they were repaired for just under a fortnight. By the end of April he was at Nomuka ("Anamoka"), where Tasman had already provisioned. From there he sailed on to Tongatapu, where he was festively received and entertained and observed a solar eclipse on 5 July. Crossing the Tonga Islands, he set course for the Society Islands after a visit to ʻEua, where he visited Tubuai, Tahiti, and systematically other islands in August and September.

On 12 October, Omai, in armour and on horseback, was taken with pomp to his home island of Huahine, where a house was then built for him. Omai's farewell to Cook was tearful, and Cook put on paper gloomy forebodings of Omai's future: "Omai was the more respected the farther he was from his native land." Omai also disregarded Cook's advice to flatter the powerful with guest gifts, which had been given to him in large quantities, and even during Cook's stay "made an enemy of every man of any importance."

Cook discovered Kiritimati on December 24 and observed another solar eclipse on Eclipse Island on December 30. On January 18, 1778, high islands appeared on the horizon, and on January 20, landfall was made on Kauaʻi. During the ten-day stay that followed, the sailors were astonished to note the cultural and linguistic affinity with faraway Tahiti. Before sailing off to the northeast to explore Nova Albion (California), found by Francis Drake in 1579, Cook named the archipelago the "Sandwich Islands" (now Hawaiʻi Islands, not to be confused with the South Sandwich Islands in the South Atlantic) after the First Lord of the Admiralty. It was to have been Cook's last great discovery.

Early in March he was off the Oregon coast, and late in March he made a month's stop on shore at Resolution Cove, Hope Bay (Nootka Sound) to overhaul the ships. He named it "King George's Sound," named an island after Bligh, and a peninsula after Clerke. Then the expedition moved northward along the coast, crossed the Aleutian Islands, pushed into the Bering Strait, until it ran aground on pack ice at 70° 44' N.

Following a westerly course, Cook then reached Asia and got as far as Cape Deshnyov, the easternmost point of the Siberian coast, before returning to the Aleutian Islands. On Unalaska he met Russian fur traders, was able to copy maps of the Aleutian Islands and the Kamchatka Peninsula, and received a letter of recommendation to the governor of Kamchatka and Petropavlovsk from a businessman named Ismailov. Through Ismailov he sent mail to the Admiralty.

When winter drove him from the high latitudes, Cook set course again for the Sandwich Islands (Hawaiʻi) on 26 October 1778, arriving at Kealakekua Bay on 17 January 1779, at the time of the Makahiki festival in honour of the god Lono. The kapu (sanctity, sacred place) otherwise imposed on the bay was lifted for the duration of the festival.

Whether he was mistaken for the god himself is a long-standing subject of dispute. What is certain is that his crew's behavior soon taught the locals otherwise. At the latest when a deceased sailor was buried in a place reserved for chiefs, the attitude of the Hawaiians must have turned against their guests. Since Cook left two days later, on February 4, 1779, no more assaults occurred. However, by the time he returned on February 11 to replace a Resolution mast damaged in the storm, relations had been ruined. A cutter theft by the locals occurred. An attempt to bring the king (aliʻi nui) Kalaniʻōpuʻu aboard the ship as a hostage in order to recover the stolen cutter (type of boat) then came to a head.

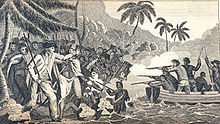

Cook was held up on the beach and mobbed by a large crowd. A first shotgun blast he fired from his double-barreled shotgun had no effect because the bullet lodged in an attacker's shield. With a second shot he killed an attacker. As he then turned to give orders, he was stabbed from behind. He fell face first into the water, was dragged out and massacred. Four Marines and several Hawaiians also lost their lives in the incident.

After the incident, Captain Charles Clerke took command of the expedition and Resolution, turning the Discovery over to Lieutenant John Gore. Clerke was wise enough to refrain from reprisals, and through the mediation of the priest and one of the King's sons, obtained at least some of the body parts of Cook and the marines, which took until 20 February, as the bodies had been dismembered and distributed to several families. In some cases they had also been burned. This was considered a tradition among the Hawaiians to honor and bury a chief after his death. Cook was identified by a burn on his right hand made years earlier in New Zealand. A burial at sea was held for him in the bay on February 21. The next day, the ships departed.

They sailed northward to Petropavlovsk, where they were kindly received by the Russians. News of Cook's death reached England by land six months before the ships returned home. His successor attempted to carry on the commission, but failed in 70° 33' N. of the pack ice, which seemed even stronger than it had been the year before. On the return voyage to Petropavlovsk, Captain Clerke died at the age of 38. Virginia-born Lieutenant Gore, who had already participated in Cook's first Pacific voyage, led the expedition back to England, where it arrived on October 6, 1780.

Cook Monument Kealakekua

Cook's End (February 14, 1779)

Monument to James Cook in Waimea (Kauaʻi) commemorating the January 1778 landing.

Memorial stone in the bay where Cook died

James Cook painted by John Webber (1776)

Portrait of James Cook (painted by William Hodges) ca. 1775-76

Poupou (Maori genealogical table), the only surviving object from James Cook's first voyage to the South Seas, 1770 gift to Joseph Banks, now in the Museum of the University of Tübingen MUT

The routes of Cook's voyages: red = 1st voyage, green = 2nd voyage, blue = 3rd voyage, blue dashed line = route of his crew after he perished.

The Resolution and Adventure ships in Tahiti's Matavai Bay, on their second voyage.

Cook's map of Newfoundland, commissioned by then Governor Hugh Palliser, published version of 1775.

Course of the first voyage to the South Seas, 1768-1771

Replica of the HMS Endeavour (ship type Whitby Cats)

Character

Cook is described as a quiet and very conscientious man. As an expedition leader, he felt very committed to his respective mission, but his constant efforts to avoid the outbreak of scurvy, which was common on sea voyages at the time, also speaks to the fact that the well-being of all involved was just as important to him as success.

When a large part of his crew and he himself fell ill on his first expedition, he cared for and comforted those who were suffering. After the 38 deaths on the first voyage, he gave a lot of thought to how the number of deceased could be reduced. On the second voyage, there were only four deaths, a remarkably low number for such a long voyage at that time.

Questions and Answers

Q: Who was Captain James Cook?

A: Captain James Cook was a British explorer, navigator and cartographer.

Q: What are some of his notable accomplishments?

A: He is most notable for the British finding the east coast of Australia, finding the Hawaiian Islands and for making the first maps of Newfoundland and New Zealand.

Q: How many times did he sail around the world?

A: He sailed twice around the world.

Q: What other areas did he explore during his trips?

A: During his trips, he explored Antarctica, North America and the South Pacific.

Q: What activities did he do on his voyages?

A: On his voyages, he spent a lot of time on science experiments and mapping new areas.

Q: Did he write any books about what he found?

A: Yes, he wrote several books about what he found during his travels.

Search within the encyclopedia