Istanbul

![]()

This article is about the Turkish city. For other meanings, see Istanbul (disambiguation).

Template:Infobox Place in Turkey/Maintenance/CountyWithoutInhabitantsOrArea

Istanbul (Turkish İstanbul [isˈtanbuɫ], from Greek εἰς τὴν πόλιν eis tḕn pólin, "into the city": see below), formerly Byzantion (Byzantium) and Constantinople, is Turkey's most populous city and its center for culture, commerce, finance, and media. With a population of around 15.5 million, the metropolitan region ranked 15th among the world's largest metropolitan regions in 2019. Moreover, with over 14 million tourists from abroad annually, Istanbul is the city with the eighth largest number of visitors in the world. The city is located on the northern shore of the Sea of Marmara on both sides of the Bosphorus, i.e. in both European Thrace and Asian Anatolia. Due to its unique transit location in the world between two continents and two sea areas, the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea, it has significant shipping traffic and two major airports, as well as two central rail-head stations and two long-distance bus stations. The Marmaray project, a railway tunnel under the Bosphorus, connects the two continents. Istanbul is therefore one of the most important hubs for transport and logistics at both international and national level.

Founded in 660 BC under the name of Byzantion, the city has a history of 2600 years. For almost 1600 years it served as the capital of the Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman Empires. As the seat of the Ecumenical Patriarch and - until 1924 - of the Ottoman Caliphate, Istanbul was also an important centre of Orthodox Christianity and Sunni Islam for centuries.

The cityscape is characterized by buildings of the Greek-Roman antiquity, the medieval Byzantium as well as the modern and modern Turkey. Palaces belong to it as well as numerous mosques, cemevleri, churches and synagogues. Due to its uniqueness, parts of the historic old town have been declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. In 2010 Istanbul was the European Capital of Culture.

Istanbul is divided by the Bosporus into a European and an Asian part (picture taken from the Galata Tower)

View of Istanbul by night

Aerial view of the Golden Horn

History

→ Main article: History of Istanbul

Development of the name

The original Greek name of the city of Byzántion (Greek Βυζάντιον, Latin Byzantium), goes back to the legendary founder of the city, Byzas, who came from Megara in central Greece. He had followed an oracle saying of Pythia. In honor of the Roman emperor Constantinus, who had Byzantion developed into the capital, the city was renamed Constantinopolis (Greek Κωνσταντινούπολις Kōnstantinoúpolis "City of Constantine") in 324. Constantinopolis is the origin of the German form Konstantinopel and numerous forms of the name in other languages. Thus Constantinople was called al-Qustantīniyya / القسطنطينية in Arabic, Gostantnubolis in Armenian, and Kushta (קושטא) in Hebrew. In many Slavic languages, however, the city was called Cari(n)grad ("City of the Emperor").

From the Ottoman conquest until 1930, there was no continuing and distinct official form of the name. In Ottoman documents, inscriptions, etc., the city was usually referred to by its Arabic-derived name form Kostantiniyye / قسطنطينيه. However, one also finds şehir-i azima ('the great city'), the Frenchized forms Constantinople and Stamboul, and from the 19th century onwards increasingly the designation Dersaâdet / در سعادت / Der-i Saʿādet / 'Gate of Bliss'. Other designations included darü's-saltanat-ı aliyye, asitane-i aliyye and darü'l-hilafetü 'l aliye and pâyitaht / پایتخت / 'Honorable Throne' in the sense of "residence".

In the Turkish dialect of the city, the name Istanbul, Astanbul / استانبول (also Istambul, Stambul) had developed alongside it, which was already in use in Seljuk times and is later attested by Ottoman and Western European records for the 16th century. Borrowing from Istanbul, Islambol / إسلامبول / 'filled with Islam' appeared on coins in the 18th century as the name of the mint at the Tavşan taşı. However, while Constantinople usually meant the entire city including some districts north of the Golden Horn and beyond the Bosphorus, the name Istanbul rather denoted the old city on the peninsula between the Sea of Marmara, the Bosphorus and the Golden Horn, which was closed off to the west by the land wall. In 1876, the name of the capital was incorporated as Istanbul in the new constitution, where Article 2 stated:

"Devlet-i Osmaniyenin payitahtı Istanbul şehridir / دولت عثمانیه نك پای تختی استانبول شهریدر / 'The capital of the Ottoman state is the city of Istanbul'"

Istanbul is probably the Turkish variant of the ancient Greek εἰς τὴν πόλιν, but more likely εἰς τὰν πόλιν ("into the city"), which in Middle Greek was pronounced something like istimbólin or istambólin. This interpretation seems conclusive, for whoever colloquially said "the city" in the Eastern Roman Empire in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages usually meant Constantinople, which, with its five hundred thousand inhabitants and its mighty walls, could not be compared to any other city in the wide area. Like ancient Rome, it was a model city; it was the economic, cultural, and political center. Constantinople, like Rome before it, was considered the center of the world. The empire itself, like its capital, therefore did not really need a name, since they were unique (the emperor did not see himself as emperor of Byzantium or Constantinople, but as emperor "urbis et orbis"). Even today, Greek speaks simply of ἡ Πόλη, ī Pólī "the city" and of its famous cuisine as the πολίτικη κουζίνα polítikī kouzína, roughly "urban cuisine" (cf. the original title of the film Cinnamon and Coriander).

On March 28, 1930, in the early days of the Republic, İstanbul became the official name of the entire city. Since the city had long been so called in a narrow sense in Ottoman writings and in the Turkish vernacular, this was not actually a new naming, but an assimilation of a long-established usage. In most European countries (except, for example, Greece and Armenia), the name Istanbul gradually replaced the name Constantinople or its variants from the linguistic usage. The ancient Greek-Roman name, however, continues to be used in specialist literature - usually with reference to the historical, pre-Ottoman Constantinople.

Byzantion

Around 660 BC, Doric Greeks from Megara, Argos and Corinth founded Byzantion, a colony on the European shore of the Bosporus. The favourable geographical position soon enabled the settlement to become an important trading centre. At the end of the 6th century, it became embroiled in the conflicts between the Persian Empire and the Greek poleis, then in the internal Greek conflicts.

In 513 BC the Persian king Darius I conquered the city, and in 478 it was occupied by Sparta for two years. Afterwards, Byzantium chose democracy as its form of government and, under pressure from Athens, joined the Attic-Delic League (until 356). In 340/339 the city withstood the siege of the Macedonian king Philip II. After the disintegration of the Macedonian Empire, the city increasingly sided with the expanding Roman Empire and became a Roman confederate in 196 BC. Byzantium lost this special status only under Emperor Vespasian. In 196 Septimius Severus had the city destroyed as punishment for supporting his opponent Pescennius Niger, but it was rebuilt. In 258 it was sacked by Goths.

In 324 Constantine I gained sole rule over the Roman Empire, and on May 11, 330, he christened the new capital Nova Roma (New Rome). However, it became better known as Constantinople. Its area quintupled within a few decades. To the west of the city wall built by Constantine, Theodosius II had a wall built from 412 onwards that still exists today, increasing the city's area from six to twelve square kilometres. Aqueducts supplied the now largest city in the Mediterranean region with water, and grain was distributed to large parts of the population.

Constantinople - Kostantiniyye - Istanbul

Eastern Roman Empire

Once again under Emperor Justinian I (527-565) Constantinople was magnificently expanded (Hagia Sophia). The city was by far the richest and largest city in Europe and the Mediterranean and successfully withstood the two sieges by Arabs in the years 674-678 as well as 717/18. Under pressure from the Seljuks, who conquered Asia Minor from the mid-11th century, the city temporarily lost its eastern hinterland. In this situation the Italian cities, above all Venice and Genoa, obtained trading privileges and extensive residential quarters on the southern shore of the Golden Horn; the Genoese, from 1267, in Pera on the northern shore. Moreover, in 1054 ecclesiastical unity between the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church had broken down. In 1171 Emperor Manuel I had the Venetians arrested and their property confiscated. Venice used the Fourth Crusade for revenge, and in 1204 Crusaders captured Constantinople. The city was sacked, numerous inhabitants were murdered, and priceless works of art were lost. Reduced to about 100,000 inhabitants, the city was the capital of the Latin Empire from 1204 to 1261. In 1261, Emperor Michael VIII succeeded in reconquering Constantinople, but he still had two decades to resist repeated plans of conquest. From this time on, however, the city was no more than the centre of a regional power, whose hinterland was successively conquered by the Ottomans from 1354 onwards. By 1400, the empire consisted only of Constantinople with its immediate environs and small remnant territories in the north (Thessalonica) and south (Morea) of Greece. Once again in 1422 the city withstood a siege by Murad II.

Ottoman Empire

On April 5, 1453, the last siege by Ottoman forces under Sultan Mehmed II began. On the morning of May 29, the "long-decayed city" was occupied. Constantinople - now officially usually called Kostantiniyye, occasionally İstanbul - became the new Ottoman capital after Bursa and Adrianople (Edirne). The partially destroyed and depopulated city was repopulated and rebuilt according to plan. The power of the empire reached its peak under Sultan Süleyman I (1520-1566), whose architect Sinan shaped the cityscape with numerous mosques, bridges, palaces and fountains. With the progressive decline of Ottoman influence in the region and the diminution of the empire by the early 20th century, Constantinople's cosmopolitan importance also suffered.

The weakness of the Empire after the Balkan War of 1912/1913 brought home to the European powers and Russia the danger of a power vacuum in the strategically important straits and raised the Oriental question of control over the straits and division of the Empire into spheres of interest. The Sultan and the Young Turks sought the support of the German Empire.

The Ottoman Empire was able to prevent the Entente's seizure of Constantinople in the First World War on the side of the Central Powers in the Battle of Gallipoli in 1915. Nevertheless, the war was lost. French and British troops occupied the metropolis from 13 November 1918. In the Peace Treaty of Sèvres of August 10, 1920, the Ottoman Empire was divided among the Allied victorious powers and also suffered enormous territorial losses. Constantinople with the straits Bosporus and Dardanelles remained occupied by the Allies for five years. Greece, in memory of Byzantium, which it claimed as Greek, demanded the "return" of Constantinople, which it wanted to make its capital.

Under Mustafa Kemal, known as Atatürk, the Turkish War of Liberation began in 1919, at the end of which the last units of Allied troops left the city on September 23, 1923. Constantinople lost its status as the seat of government to Ankara in that year, with which the new republic wanted to distance itself from the tradition of the Ottomans.

Turkish Republic

The expulsion of the first of the two large Christian minorities, the Armenians, began during the First World War. Non-Muslims had made up the majority of the population until about 1890, from which time a steady immigration into the city began, whose population exceeded the million mark a few years later. Armenians had increasingly moved in since the 17th century, so that by 1850 there were over 220,000 living in Constantinople. This meant that they made up perhaps a quarter to a third of the population. The Allies sought their support during World War I. On April 24, 1915, two months after the start of the Battle of Gallipoli (fighting for the Dardanelles), which took place between February 19, 1915 and January 9, 1916, the government had Armenian civilians deported from Constantinople for the first time. Officially there were 235, probably more than 400 of the 77,835 Armenians still living in the capital at that time. The Armenian genocide took place mostly in Anatolia; Istanbul's Armenians were largely spared until 1923. In Istanbul, the persecutions were aimed at deporting the Armenian elite. In the deportation process, starting on April 24, 1915, by order of Interior Minister Mehmet Talât Bey, leading figures of the Armenian community in Istanbul and later in other localities were arrested and deported to concentration camps near Ankara. After the adoption of the Deportation Law of May 29, 1915, they were forcibly relocated, tortured, dispossessed and many murdered. Therefore, April 24 is observed as Genocide Remembrance Day in Armenia. On the night of April 25, in a first wave, 235 to 270 Armenian community leaders from Istanbul (mainly clergymen, doctors, publishers, journalists, lawyers, teachers, politicians) were arrested based on the decision of the Ministry of Interior. A second wave of arrests in Istanbul involved up to 600 people, according to information from investigations.

The exact number of inhabitants of the city can hardly be determined. Around 1920 it was between 800,000 and 1.5 million. The only thing that is clear is that after four decades of strong population growth the number of inhabitants virtually collapsed. In 1927 one counted only 691,000 inhabitants; while the non-Muslim population had been about 450,000 in 1914, it counted only 240,000 in 1927. With that, however, they still represented almost one third of the population at that time.

84% of the population lived in cities with less than 10,000 inhabitants at that time, which, with the rural exodus slowly setting in, held enormous potential for immigration to Istanbul, which began to unfold in the 1950s. While the Greeks, probably about 1.2 million, had to leave Anatolia, all Greeks who had lived in the capital on 30 October 1918 were allowed to stay. But despite this special agreement of 1926, more Greeks left; an extreme shortage of artisans occurred. In 1942, non-Muslims were made to pay a special property tax (Varlık Vergisi), and in 1955 almost the entire Orthodox population was expelled from the city in the Istanbul pogrom. Of the approximately 110,000 Greeks, about 2,500 remained in Istanbul. Today, about 60,000 Armenians and 2,500 Greeks live in the city.

Istanbul grew rapidly from the 1950s onwards, it attracted and still attracts numerous people from Anatolia. Since the 1990s, many Eastern Europeans have been coming to the metropolis. Large-scale construction projects were undertaken; they could hardly keep up with the rapid population growth. Moreover, they took little account of existing structures. Istanbul expanded far into the surrounding countryside; numerous villages and towns in the surrounding area are now part of the metropolis. Accordingly, Istanbul was elevated to the status of a metropolitan municipality in 1984.

In 1994, the current President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan became mayor as a candidate of the Islamist Refah Partisi (RP) (Welfare Party). The later mayor Mevlüt Uysal is a member of the Islamic conservative Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP). In November 2003, the city was rocked by a series of serious attacks. The attack in an Internet café on February 9, 2006, claimed the life of one person, and six people were injured by an attack in a supermarket four days later.

On 28 May 2013, demonstrations began in Taksim Square. They began as protests against a planned shopping centre and against the cutting down of Gezi Park, respectively; after a brutal police operation on 31 May 2013, they turned into protests against the Erdogan government and Erdogan's style of government (→ Protests in Turkey 2013).

Fires

The frequent large fires triggered social and economic crises and had a great influence on the development of the city. Triggers were, for example, the regularly occurring earthquakes, the trade in explosives, carelessness in households and workshops, and arson. Thus, between 1883 and 1906, 229 fires occurred with the destruction of 36,000 houses. The 1690 fire in the Grand Bazaar destroyed goods with an estimated value of 3 million kuruş (about 2 million gold pieces). The largest fires in the city's history occurred in 1569, 1633, 1660, 1693, 1718, 1782, 1826, 1833, 1865, and most recently in 1918 with 7,500 houses destroyed. The traveller Salomon Schweigger writes around 1580:

"There have been a number of fires in the city. In one of them the fire had seized a prison, at the city gate near the canal or harbour. The prisoners in the upper part of the tower forced their way to the door, opened it, and escaped; the others, who numbered about seventy, perished inside. A large place, like a large village, was burned, but it was not noticeable in the city. When a fire breaks out, no one who desires to lash out runs to it, except the janissaries, who are ordered not to lash out, but to bring the flame by breaking and tearing down the nearest houses.

- Salomon Schweigger: Zum Hofe des türkischen Sultans. Leipzig 1986 (reprint), p. 94

Some of the reasons for the devastating effect of the fires lay in the dense development of the city, which until well into the 20th century consisted mainly of wooden houses, the frequently blowing winds and the settlement structure, which often consisted of largely self-contained quarters (mahalle) with cul-de-sacs, making it difficult to fight fires quickly. After major fires, decrees were issued that houses near social, economic, and public buildings should also be of stone or brick. However, these decrees were not always obeyed. In Ottoman times, firefighting was the responsibility of the Water Carriers Guild and the Janissaries, among others, and from 1718 fire engines with water pumps and newly established fire brigades were used.

Various names of Istanbul on Ottoman postmarks (1880 to 1925)

The name Islambol / إسلامبول on a coin of 1203 H. (1788/89 in the Gregorian calendar)

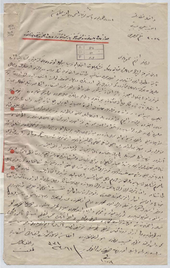

![From the campaign diary of Suleyman I (1521): "[...] and departed for the city of Istanbul [...]" (modern emphasis).](https://alegsaonline.com/image/260px-Istanbul_1521.png)

From the campaign diary of Suleyman I (1521): "[...] and departed for the city of Istanbul [...]" (modern emphasis).

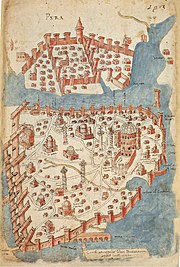

Representation of Constantinople by Cristoforo Buondelmonti, 1422

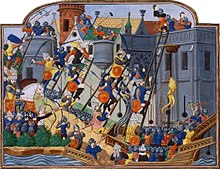

The conquest of Constantinople according to a French chronicle of the 15th century

View of Istanbul around 1910

A British warship overlooking the Golden Horn. Allied occupation of Istanbul 1918

Order of the Ministry of the Interior under Talât Pasha on 24 April 1915

Consequences of a fire in the old city of Istanbul

Population

Population development

→ Main article: Population development of Istanbul

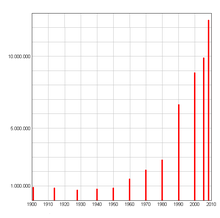

The population increased from 680,000 in 1927 to 1.3 million in 1955, 2.5 million in 1975, 9.8 million in 2005, to 13.1 million in 2010 and 14.7 million in 2015. Of the 13,120,596 residents in 2010, about 65% lived in the European part of Istanbul and about 35% lived on the Asian side.

The following overview shows the population figures according to the respective territorial status. Until 1914, these are mostly estimates, with great uncertainties. The conspicuous decline in the population around 1900 to 1927 is an expression of the expulsion of the Greek population. The figures from 1927 to 2000 are results of censuses. The figures from 2005 and 2006 are based on projections, and those from 2007 onwards are results of censuses. The doubling of the population between 1980 and 1985 is due to in-migration, natural population increase and also to extensions of the city limits. The population figures in the following table refer to the city in its political boundaries, excluding independent suburbs.

Ethnic minorities

Kurds and Zaza together form the largest group of ethnic minorities in Istanbul. The largest among the traditional Christian populations still living there are Armenians. The number of Armenians in Istanbul is given by the government as 45,000, which is about 0.36 percent of the population. About 17,000 Arameans make up the second largest Christian ethnic group after that. The 22,000 Jews form the second largest religious minority. Some of the approximately 25,000 Bosporus Germans come from families that have often lived permanently in Constantinople or Istanbul since the first half of the 19th century. Some of the approximately 1,650 Greeks are among those who have been original residents for many generations. The number of Russians, according to the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, is estimated at around 100,000, and that of the Chinese is said to be even higher. Istanbul was also a place of refuge for Russians due to the communist October Revolution.

Other population groups are Lasen, Arabs, Circassians and Roma. A small Polish community exists in Polonezköy (German "Polendorf", Polish Adampol), which has just over 400 inhabitants.

Religions

Today, the vast majority of the population professes Islam. At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the majority of the inhabitants were still non-Muslims, such as the Greek Orthodox Christians, the Syrian Orthodox Arameans, the Armenian Christians and the Sephardic Jews. They now form only small minorities. In addition to Islamic sacred buildings, there are also Christian churches of various denominations and synagogues in prominent locations, such as Saint Stephen (former seat of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church) at the Golden Horn or the Agia Triada at Taksim Square. In some parts of the city, such as the Kuzguncuk neighbourhood, the institutions of different religions are in close proximity.

The city is the seat of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, to whom, among other things, most Orthodox churches in modern Turkey are subordinate and who also enjoys the primacy of honour over all Orthodox churches. Furthermore, an Armenian archbishop and the Turkish chief rabbi reside here.

Muslims

Muslims of different faiths form the largest religious group. Most of them are Sunnis, 15 to 30 percent are Alevis. There are a total of 2,562 mosques, 215 small mosques (Turkish mescit) and 119 Turkish mosques.

On September 2, 1925, Kemal Atatürk banned the numerous dervish orders (Tarīqas). Most followers of Sufism, the Islamic mysticism, then operated in secret or went abroad (e.g. to Albania). Some of them have a large following today. In order to escape the ban, however, they usually appear as "cultural associations". The İsmail-Ağa community in Fatih is known throughout the country.

Christians

→ Main article: Christianity in Turkey

The city is the seat of the Ecumenical Patriarch, who acts as primus inter pares as the supreme representative of the Orthodox churches. The Greek Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, with his seat in Fener, has been Bartholomew I since 1991. He is the 270th successor of the Apostle Andrew and thus the de facto (honorary) head of some 300 million Orthodox Christians. The seats of the Armenian Patriarch, the Archbishop of the Syrian Orthodox (Aramaic) community and an apostolic vicar of the Roman Catholic Church in Turkey are also located in Istanbul.

Istanbul is home to nearly 85,000 Christians, about 85 percent of the total Christians in Turkey, whose number nationwide is about 100,000. The number of Armenians amounts to about 45,000 (35 churches), that of the Arameans to 12,000, of the Bosporus Germans to 10,000 and of the Greeks to 1,650 (5 churches). Some Orthodox churches are under the jurisdiction of other patriarchates, such as the Bulgarian Orthodox Church of St. Stephen. In addition to the Levantines and other non-Orthodox parishes, there is also a German Protestant and Catholic parish each, as well as an Austrian Catholic parish around St. George's College.

Jews

The Sephardic Turkish Jews have lived in the city for over 500 years. They fled the Iberian Peninsula in 1492 to escape forced baptism as a result of the Edict of the Alhambra. Sultan Beyazit II. (1481-1512) sent a fleet to Spain to rescue the Sephardic Jews. More than 200,000 of them fled first to Tangier, Algiers, Genoa, and Marseilles, and later to Salonika and Istanbul. The Sultan granted refuge to over 50,000 of these Spanish Jews.

Istanbul was home to only about 17,000 Jews in 2016, down from 22,000 before 2010, and they make up less than 0.2 percent of the population. A total of 16 synagogues can be found in the city, the most significant of which is the Neve Salom Synagogue in the Beyoğlu district, inaugurated in 1951, which has been the site of three terrorist attacks (on 6 September 1986, 1 March 1992 and 15 November 2003). Istanbul is the seat of the Hahambaşı, Turkey's chief rabbi. The only Jewish museum in Turkey, the 500th Yıl Vakfı Türk Musevileri Müzesi, is located in Beyoğlu. The museum was completed on November 25, 2001 and the current curator is Naim Güleryüz.

Development of the housing situation

The districts of Bakırköy and Beylikdüzü in the European part, which together have a population of around 400,000, and Maltepe in the Asian part, which has a similar population, have grown rapidly since the 1980s and consist mainly of high-rise buildings. In particular, Etiler in the Beşiktaş district has become one of the most affluent neighborhoods since the 1990s.

Now that most of the gaps between buildings in and near the city center have been closed, there are hardly any opportunities for recreation there, except for the frequently frequented Gülhane and Yıldız Park.

The immense immigration led to the emergence of illegal settlements (Gecekondus) on the periphery, of which Istanbul has the most in Turkey. Almost a quarter of Istanbul's population lives in the approximately 750,000 residential buildings of such settlements. More than 50 percent of their residents are unemployed or uninsured. The crime rate is higher than in other neighbourhoods, socially marginalised population groups and a low presence of state organisation also characterise these neighbourhoods.

The largest gecekondu neighbourhoods are on the European side. Tensions are high in Fatih, such as in Balat, the neighbourhood once inhabited by Jews, which was subject to a restoration programme until 2007, and Sulukule, where mainly Roma live, who are resisting the relocation of 3,500 residents. Gazi Mahallesi and Habipler in the Sultangazi district, which is home to around 450,000 people, as well as Seyrantepe in the Şişli district and Tarlabaşı in the Beyoğlu district (245,000) are added to the list. On the Asian side, these are Gülsuyu in the Maltepe district (420,000). Individual gecekondus are predominantly found in the districts of Bağcılar, Bahçelievler, which had a population of around 800 in 1950 but nearly 600,000 in 2007, Küçükçekmece (670,000), Pendik (540,000) and Sultanbeyli (280,000).

Michael Thumann reports on gentrification in Tarlabaşı, where old property owners are being expropriated with the approval of the AKP government in order to build new buildings.

Crime

The crime rate in Istanbul dropped by 25 percent from 76,285 registered crimes in 2006 to 57,123 registered crimes in 2007, and the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality has decided to install 800 to 900 security cameras.

The Catholic Basilica of St. Anthony in Beyoğlu (formerly Pera)

Population development over the last 100 years

.jpg)

Kurds celebrate Newroz in Istanbul

Mevlevi dervishes in Istanbul

Gecekondu neighborhood in the Dolapdere district near Beyoğlu and Taksim.

Residential building in Maltepe

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the name of Istanbul in Turkish?

A: The name of Istanbul in Turkish is İstanbul.

Q: What is the population of Istanbul?

A: The population of Istanbul is estimated to be between 11 and 15 million people, making it one of the largest cities in Europe.

Q: Is Istanbul the capital city of Turkey?

A: No, although it is the largest city in Turkey, it is not the capital. Ankara is the capital city of Turkey.

Q: When was Constantinople renamed as Istanbul?

A: Constantinople was renamed as Istanbul in 1930.

Q: Who founded Byzantion (the original name for Constantinople)?

A: Byzantion (the original name for Constantinople) was founded by Greeks from Megara in 667 BC and named after their king, Byzas.

Q: Who captured Constantinople at one point during its history?

A: During its history, Constantinople was captured by Crusaders at one point.

Q: When did Hagia Sophia get built? A: Hagia Sophia got built when Constantine moved the capital of the Empire from Rome to there, as New Rome (Latin : Nova Roma; Greek : Νέα Ρώμη , Nea Rómi ) , renaming the city Constantinople , after his name .

Search within the encyclopedia