Iranian Revolution

![]()

This article is about the concrete revolution in Iran. For the abstract idea of an Islamic revolution, see Revolution export#Islamic revolution.

The Islamic Revolution (Persian انقلاب اسلامی Enqelāb-e Eslāmi), also called the "Iranian Revolution" by secular groups, was a multi-faceted movement that led to the 1979 ouster of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the end of the monarchy in Iran. It is also called Revolution 57 (Enghelāb-e Punjah o Haft), after the revolutionary year 1357 in the Iranian calendar. The symbolic figure and later revolutionary leader was the Ayatollah Ruhollah Chomeini, who from 1979 onwards, against other revolutionary and secular groups, enforced his state concept of the rule of the clergy (Welāyat-e Faqih, "governorship of the jurist"), partly by force, and became the new head of state.

The first demonstrations against the Shah led by Ruhollah Khomeini took place in June 1963. The protests, supported by the Freedom Movement (Nehzat-e Azadi) around Mehdi Bāzargān, a member of the National Front party alliance, were intended to prevent the reform program of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's White Revolution, especially the abolition of large-scale land ownership and the introduction of women's suffrage.

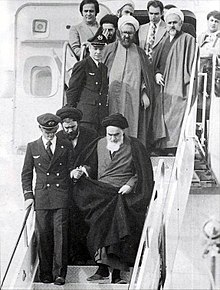

Following a political liberalization in 1977 under pressure from U.S. President Jimmy Carter, the demonstrations initiated by Khomeini revived in January 1978. Between August and December 1978, strikes organized with the support of the National Front paralyzed the country's economy. The Shah left the country in mid-January 1979 and two weeks later Ayatollah Khomeini, who had been deported abroad in 1964, returned from his French exile to Tehran, where he was greeted by a cheering crowd. The constitutional monarchy finally collapsed on February 11, 1979, at the latest, when guerrilla groups and armed Islamist revolutionaries attacked the parts of the army loyal to the Shah in street battles. On April 1, 1979, the previous form of government, the monarchy, was abolished as a result of a previously held referendum and replaced by the new form of government, the Islamic Republic.

Ruhollah Khomeini on his return from exile at Tehran airport on February 1, 1979. Top left: Sadegh Ghotbzadeh

Previous story

The Shiite clergy (ʿUlamā') has always had great influence on that part of the Iranian population that was religious and conservative and rejected Western influences in Iranian society. That the clergy was a significant political force was evident in Iran's recent history in the 1891 tobacco movement, which opposed a concession granted by Nāser ad-Din Shah, who had awarded all tobacco trade in Iran to the British Imperial Tobacco Corporation.

A few years later, Shiite clerics also participated in the overthrow of the absolutist monarchy and the establishment of a constitutional monarchy with a constitution and a parliament within the framework of the Constitutional Revolution (1905 to 1911). During the Constitutional Revolution there were heated discussions between the clergy and the bourgeois forces as to what role Islam should play in the constitution. In his writings, revolutionary leader Khomeini referred directly to Sheikh Fazlollah Nuri, who had been hanged by the constitutionalists in 1909, and described him as a role model who had fought for the supremacy of religion in Iran's political system. Nuri had enforced in the Constituent Assembly that a commission of Shiite clerics had to examine every law passed by parliament to ensure that it did not contradict the laws of Islam; otherwise it was null and void.

Decades later, the expected clashes between the clergy and Reza Shah Pahlavi took place. In 1927, he replaced the Islamic laws and courts that had been in force until then with a modern legal system of a Western style, banned the wearing of the hijab, and introduced co-educational education in schools.

In 1941, Reza Shah Pahlavi was forced to resign under British pressure following the Anglo-Soviet invasion. His son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi succeeded him on the throne. Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi sought reconciliation with the clergy and invited the Ayatollahs who had fled to Iraq to return to Iran.

In 1953, an operation conducted by the intelligence services of the United States and Great Britain led to the overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh. The intelligence operation, which went down in history as Operation Ajax, further consolidated Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's hold on power. Mossadegh had implemented the nationalization of the oil industry in Iran to stop the exploitation of Iran's oil fields by the British Anglo-Persian Oil Company. In doing so, he triggered an international crisis (Abadan Crisis) that ultimately led to his overthrow.

The Rise of Ayatollah Khomeini

Khomeini's criticism of the White Revolution

→ Main article: Riots in Iran in June 1963

The leader of the Islamic Revolution, the Shiite cleric Ruhollah Khomeini, became known to a wider audience in Iran in 1963 by vehemently opposing the Shah's reform program, which would later be titled the White Revolution. Khomeini saw the program, whose main points consisted of land reform, the empowerment of women, and a literacy campaign, as an attack on Islam. Although Khomeini denounced the referendum on the reform program as an anti-God scheme and called on all believers not to vote, on January 26, 1963, 5,598,711 Iranians spoke in favor and only 4,115 against.

On June 3, 1963, during the Ashura celebrations, Khomeini personally attacked the Shah in a speech at Ghom's Faizieh School, delivering a speech against the tyrant of our time:

"This government is against Islam. Israel is against having the laws of the Koran in Iran. Israel is against the enlightened clergy ... Israel is using its agents in this country to eliminate the opposition directed against Israel ... the Quran, the clergy ... O Shah, O exalted ruler, I give you good advice to give in and desist (from these reforms). I do not want to see the people dancing for joy on the day when you will leave the country on the orders of your masters, just as everyone rejoiced when your father once left the country."

After this speech, Khomeini was arrested on June 5, 1963.

Khomeini's speech against the White Revolution reforms was accompanied by violent demonstrations in Ghom, Shiraz, Mashhad and Tehran. More than 10,000 demonstrators marched through the streets of Tehran on June 5, 1963, to protest Khomeini's arrest. Prime Minister Asadollah Alam called in the army to help after he could only leave the seat of government in an armored vehicle. For the first time since World War II, Tehran was under a state of emergency. Troops marched in the streets and demonstrators were shot at. Thousands were injured. The death toll was put at 20 by Prime Minister Alam. Khomeini and his supporters spoke of 15,000 demonstrators dead. According to a post-Islamic Revolution investigation by Emad al-Din Baghi, 32 demonstrators had died in violent riots in Tehran on June 5, 1963. The resistance to Mohammad Reza Shah under Khomeini had been forming. Today, leading politicians of the Islamic Republic of Iran declare that the protests in June 1963 were the birth of the Islamic Revolution.

After eight months of house arrest, Khomeini was released and began anew to agitate against the Shah and his government. In November 1964, he was arrested once again and deported to Turkey.

Khomeini in exile

After his initial stay in Bursa (Turkey), he was able to travel to Iraq in October 1965 at his insistence, settling first in Baghdad, then in Najaf, a holy place of the Shiites. He was able to move there with relative freedom and continue his studies and teaching. It was in this climate that Khomeini's most important work was written: The Islamic State (1970). In this work he developed the state principle of welayat-e-faghih ("rule of the supreme jurist"). In his agitation, he gradually succeeded in discrediting the idea of social progress by aligning it with the West, which had been one of the foundations of the Shah's reform program, and developed his own, Islamic ideology of progress. In doing so, he drew on Jalāl Āl-e Ahmad's critique of the Westernization of Iran. Al-e Ahmad spoke of Westernization (gharbzadegi) as a plague that was poisoning Iranian society. Another important contribution to make Shi'ite Islam, which was regarded as backward-looking, appear as progress-oriented were the publications of Ali Shariati. For him, Islam showed the way to liberate the Third World from the yoke of colonialism, neo-colonialism and capitalism. Morteza Motahhari's popular sermons on Shiite Islam's struggle against injustice in the settlement of Mohammad's succession did much to mobilize his audience for the new struggle against the perceived injustices of the Shah regime.

One of Khomeini's central themes was that revolt, and especially the martyr's struggle against injustice and tyranny, was central to Shi'ite Islam and that Muslims should follow Islam and neither the Western way (liberalism and capitalism) nor the Eastern way (communism): Na Sharghi Na gharbi Jomhuriyeh Eslami (Neither East nor West [but an] Islamic Republic).

On 6 October 1978 Khomeini was expelled from the country by Saddam Hussein and deported to France. Only in Neauphle-le-Château, his place of residence in France - in Najaf Khomeini was only one Ayatollah among many - was it possible for Khomeini to draw attention to himself with the possibilities of the international press and to force the dissemination of his speeches by means of tape recordings in Iran. Amir Taheri lists 132 radio, television and press interviews in the few months. Beheshti played a decisive role in the dissemination in Iran.

The opposition movement

Despite the allegedly rigorous crackdown by the Shah and his secret service SAVAK, three important opposition movements were able to develop:

- The communist Tudeh Party, which was officially banned but operated successfully underground, mainly engaged in peaceful protest by organizing strikes and demonstrations. The Maoist or Marxist-influenced People's Mujahideen waged armed guerrilla warfare.

- A second opposition movement was the National Front (also known as the National Resistance Movement), a coalition of various parties founded by Mossadegh and classified as center-left. A prominent leader of this movement was Mehdi Bāzargān.

- The third opposition movement against the Shah, which was decisive for the revolution, was at its core the Association of the Fighting Clergy (Jame'e-ye Rowhaniyat-e Mobarez), founded in 1977. With roots going far back, the party was formed in secret by a group of Islamic clerics in 1977 to prepare for the overthrow of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. It is the oldest clerically oriented party in Iran today. Its founding members were Ali Khamene'i, now the "supreme leader" of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Morteza Motahhari, Mohammad Beheshti, Mohammad-Javad Bahonar, Ali-Akbar Rafsanjani and Mofatteh. Motahhari, in one of his writings, explicitly spoke of the need for an "Islamic Revolution in Iran" and defined as its goals: 1. restoration of the hallmarks of religion; 2. creation of radical religious reform in the country; 3. security for the oppressed; and 4. restoration of the Hadd punishments.

The Association of Struggling Clergy was supported by the Society of Lecturers of Religious Seminaries (Jame'eh-ye Modarresin Hozeh-ye Elmiyeh), which represented the teachers of religious schools, the Association of Islamic Coalition (Hayat-e Mo'talefeh Eslami), which was mainly supported by merchants from the bazaar, and the Society of Islamic Engineers (Jame'eh-ye Eslami Mohandesin), which was formed by technocrats who rejected the Shah's Western-oriented policies.

Khomeini in Neauphle-le-Château before Western media

Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi at the presentation of land deeds

Search within the encyclopedia