Islam

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Islam (disambiguation).

![]()

This article provides an overview of the religious history of Islam. The political, cultural and social history is presented in the article Political and Social History of Islam.

Islam is a monotheistic religion founded in Arabia in the early 7th century AD by the Meccan Muhammad. With over 1.8 billion members, Islam is today the world religion with the second largest membership after Christianity (approx. 2.2 billion members).

Islam is also commonly referred to as the Abrahamic religion, the prophetic religion of revelation, and the book or scriptural religion.

The Arabic word Islām (islām / إسلام) is a verbal noun to the Arabic verb aslama ("to surrender, to surrender"). It literally means "to surrender" (to the will of God), "to submit" (under God), "to surrender" (to God), often rendered simply as surrender, devotion, and submission.

The term for the one who belongs to Islam is Muslim. The plural form in German is Moslems or Muslims, Muslimas or Musliminnen.

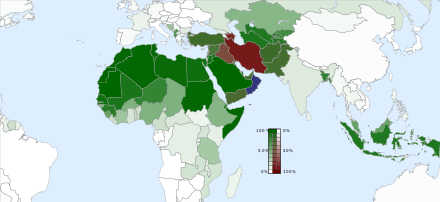

The ten countries with the largest share of the world's Muslim population are Indonesia (12.9%), Pakistan (11.1%), India (10.3%), Bangladesh (9.3%), Egypt and Nigeria (5% each), Iran and Turkey (4.7% each), and Algeria (2.2%) and Morocco (about 2%). Together, they are home to more than two-thirds of all Muslims. The most important supranational Islamic organization is the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), based in Jeddah. It has 56 member states in which Islam is the state religion, the religion of the majority of the population or the religion of a large minority. Partially Muslim European countries include Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, northern Macedonia, and Turkey (which is geographically only partially in Europe). Many other countries have Muslim minorities.

The main textual basis of Islam is the Qur'an (Arabic القرآن al-qurʾān 'reading, recitation, recital'), which is considered to be the speech of God revealed to the Prophet Muhammad.

The second basis are the hadiths (Arabic حديث, DMG ḥadīṯ 'narration, report, communication, tradition') on the Sunnah of Muhammad (Sunnah, Arabic سنة 'custom, customary way of acting, traditional norm'), who as the "messenger of God" (Rasūl, Arabic رسول 'messenger, emissary, apostle') is a role model for all Muslims.

The norms resulting from these texts are referred to in their entirety as sharia (شريعة / šarīʿa in the sense of "way to the watering place, way to the water source, clear, paved way"; also: "religious law," "rite").

Two women and a man at the Selangor Mosque in Shah Alam, Malaysia

Entrance to the Mosque of the Prophet Mohammed in Medina

Star and crescent moon: the hilal, a symbol of Islam

States with an Islamic population share of more than 5%. Green : Sunnis, Red : Shiites, Blue: Ibadis (Oman)

Pilgrims at the prayer of supplication in Mecca, in the middle ground the Kaaba

Directions

Throughout history, numerous groups have emerged within Islam that differ in terms of their religious and political teachings.

Kharijites

→ Main article: Kharijites

The Kharijites, the "strayers," are the oldest religious current in Islam. Characteristic of their position was their rejection of the third caliph ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān as well as the fourth caliph ʿAlī ibn Abī Tālib. The Kharijites also rejected Quraysh supremacy and held that the "best Muslim" should receive the caliphate, regardless of his or her family or ethnic affiliation.

By 685, their movement had already splintered into several subgroups, of which the Azraqites were the most radical and violent. It was in permanent war with the counter-caliph ʿAbdallāh ibn az-Zubair and the Umayyads. Gradually, however, the individual factions were crushed by the ruling caliphs or driven into exile on the periphery of the Arabian Empire. Thus, the majority of the Kharijites had already been annihilated under the first Abbasid caliphs.

Only the moderate current of Ibadites has survived to the present, but it has a total of fewer than two million followers, who live mainly in Oman, the Algerian Sahara (M'zab), the Tunisian island of Djerba, Libya's Jabal Nafusa, and Zanzibar.

Shia

→ Main article: Shia

The Shia is the second religious-political current that formed in Islam. Its name is derived from the Arabic term shīʿa (شیعه / šīʿa / 'followers, party'), which stands for "party of Ali. The Shiites believe that after the Prophet's death, it was not Abū Bakr but Muhammad's cousin and son-in-law ʿAlī ibn Abī Tālib who should have become caliph.

There are numerous subgroups within the Shia. The numerically largest group is the Twelver Shiites, who are widespread especially in Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, India, Pakistan and Lebanon. They believe that the imamate, i.e., the claim to the Islamic ummah, is inherited among twelve descendants of Muhammad. The twelfth Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdī, disappeared at the end of the 9th century and will not return until the end of time. The twelve imams are considered holy by the Twelver Shiites, and the places where they are buried (including Najaf, Karbala, Mashhad, Samarra) are important Twelver Shiite pilgrimage sites.

The second largest Shiite group is the Ismailis, who live predominantly on the Indian subcontinent (Mumbai, Karachi and northern Pakistan) and in Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Yemen and East Africa. A breakaway from the Ismailis is Drusianism, which emerged in the early 11th century.

Other Shiite groups include the Zaidites, the Nusairians and the Alevis. Like the other Shiites, the Zaidites believe that Ali was better than the first two caliphs, Abu Bakr and Umar ibn al-Chattab, but they recognize their caliphate as legitimate. The relationship of the Alevis and Druze to Islam is ambivalent. While some followers of these communities still consider themselves Muslims, others see themselves as outside Islam.

Babism and Bahaism developed in the 19th century on the basis of the Twelver Shia. While Babism had already disappeared in the 19th century, Bahaism developed into an independent religion.

Theological schools

Over the centuries, various theological schools have also emerged in Islam. One of the earliest of these schools was the Qadarīya, which emerged in the early 8th century and is named after the Arabic term qadar, which generally refers to an act of determination; it is usually translated as fate or destiny (providence). The Qadarites held that not only God but also man had a qadar of his own and thus sought to limit God's omnipotence. They thus appear as representatives of a doctrine of human freedom of will. With this doctrine, they were opposed at that time to another group, the Murji'a, who, among other political views, distinguished themselves by a predestinatian doctrine.

After the Abbasids began to promote theological disputation (Kalām) in the late 8th century as a means of combating non-Islamic doctrines, the Muʿtazila, which cultivated this form of disputation, developed into the most important theological school. Muʿtazilite dogmatics was strictly rationalist in orientation and attached fundamental importance to the principle of "justice" (ʿadl) and the doctrine of the unity of God (tauhīd). By "justice," Muʿtazilites here did not mean social justice, but the justice of God in his actions. According to muʿtazilite doctrine, God himself is bound by the ethical standards that human beings develop with the help of the intellect. This includes that God rewards the good and punishes the bad, because in this way human beings, with their free will, have the opportunity to acquire merit. The main consequences that resulted from the second principle, the doctrine of the unity of God, were the denial of the hypostatic character of the attributes of God's being, e.g., knowledge, power, and speech, the denial of the eternity or uncreatedness of God's speech, and the denial of any similarity between God and His creation. Even the Koran itself, as God's speech, could not claim eternity according to the muʿtazilite doctrine, since there must be nothing eternal and thus divine besides God.

The Muʿtazila received ruling support under the three Abbasid caliphs al-Ma'mūn (813-833), al-Muʿtasim (833-842), and al-Wāthiq (842-847), and later under the Buyid dynasty. To this day, moreover, muʿtazilite theology continues to be cultivated in the realm of the Twelver Shia and the Zaidite Shia.

Sunniism as majority Islam

→ Main article: Sunni

Sunnism emerged between the late 9th and early 10th centuries as a countermovement to the Shia and the Muʿtazila. The underlying Arabic expression ahl as-sunna (أهل السنة / 'people of the Sunnah') emphasizes alignment with the Sunnat an-nabī, the Prophet's way of acting. The extended form ahl as-sunna wa-l-dschamāʿa (أهل السنة والجماعة / 'people of the Sunnah and community'), also common, emphasizes the comprehensive community of Muslims.

Among the earliest groups to use expressions such as ahl as-sunna or ahl as-sunna wa-l-dschamāʿa were the Hanbalites, the followers of the traditional scholar Ahmad ibn Hanbal. In contrast to the Muʿtazilites, they taught the Qur'an to be inerrant, rejected the controversial theology of the Kalām, and regarded only the statements in the Qur'an and hadiths as well as the traditions about the "ancients" (ahl as-salaf) as authoritative. They rejected all other theological statements as inadmissible innovations. Around the turn of the 10th century, various theologians such as al-Qalānisī and Abū l-Hasan al-Ashʿarī attempted to justify this doctrine with rational arguments. The doctrine developed by al-Ashʿarī was further developed by later scholars such as al-Bāqillānī and al-Ghazālī and has become the most important Sunni theological school. The second Sunni theological school besides this Ashʿarīyya is the Maturidiyya, which refers back to the transoxanic scholar Abū Mansūr al-Māturīdī.

Today, the Sunnis form the numerically largest grouping within Islam, with about 85 percent. Characteristic of the Sunnis as a whole is that they revere the Prophet's first four successors as "rightly guided caliphs" (chulafāʾ rāschidūn), in contrast to the view shared by most Shiites, according to which ʿUṯmān's conduct made him an infidel, and the view of the Kharijites and Ibadites according to which both ʿUṯmān and ʿAlī were infidels and therefore their killing was legitimate. In addition, Sunnism attaches itself to a certain number of hadith collections that are considered canonical, the so-called Six Books. The most important of these is the Sahīh al-Bukhari. Finally, Sunnism is characterized by the restriction of Quranic recitation to a certain number of accepted readings of the Quran.

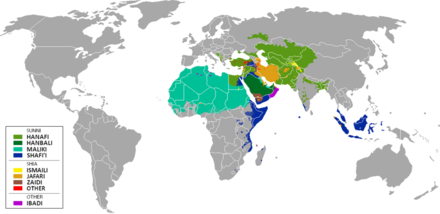

Directions of the Islamic doctrine of norms

→ Main article: Madhhab

Only a few decades after the Prophet's death, Muslims felt the need to obtain information on certain questions of lifestyle. These concerned the area of worship as well as living together and legal relations with other people. Recognized authorities such as the Prophet's cousin ʿAbdallāh ibn ʿAbbās served this need by issuing expert opinions (fatwas) on the points in question. In the beginning, these opinions were largely based on their own subjective views (Raʾy). In the course of the 8th century, local schools of scholars emerged in various places-in addition to Mecca, especially Medina, Kufa, and Syria-which collected opinions of earlier authorities on certain issues and at the same time established principles for the establishment of norms (fiqh). While the school of Medina with Mālik ibn Anas attached great importance to consensus (Idschmāʿ), Abū Hanīfa in Kufa worked more with the methods of analogical reasoning (Qiyās) and their own judgmental effort (Idschtihād). Mālik's school spread mainly in Egypt, and AbūḤanīfa's school in Khorasan and Transoxania.

In the early 9th century, the scholar ash-Shāfiʿī endeavored to establish a synthesis between the Malikite and Hanafite directions and, within this framework, developed a comprehensive theory of norm-finding that included certain principles of textual hermeneutics to be applied in the interpretation of the Qur'an and hadiths. Because ash-Shāfiʿī had spoken out very strongly in his works against the principle of taqlid, the unreflective adoption of the judgments of other scholars, it took until the early 10th century for a separate school to form around his teachings. The first center of the Shāfiʿites was Egypt. From there, the Shafiite doctrine (madhhab) later spread to Iraq and Khorasan as well as to Yemen.

After Hanbalism developed its own doctrine of norms in the 11th century under the influence of the Baghdad cadi Ibn al-Farrā' (d. 1066), four doctrines of norms were recognized as orthodox in the realm of Sunni Islam: the Hanafites, the Malikites, the Shafiites and the Hanbalites. Today, there is a tendency to recognize a total of eight schools of thought as legitimate. The Ibadiyya and the Shiite Zaidiyya are counted as separate schools of thought. The Salafis, on the other hand, reject adherence to a madhhab as an illegitimate innovation. Today, the teaching of Islamic norms is further developed in international bodies, the most important of which is the International Fiqh Academy in Jeddah, which belongs to the Organization of Islamic Cooperation.

Sufi currents

→ Main article: Sufism

Sufism (تصوف / taṣawwuf) is a religious movement that emerged among the Muslims of Iraq in the 9th century. The Sufis cultivated various ascetic ideals such as renunciation of the world (zuhd) and poverty (faqr) and waged war against the libidinal soul. In accordance with Quranic injunctions (cf. Sura 2:152; 33:41f), they devoted the greatest attention to the remembrance (dhikr) and praise (tasbih) of God. Other important Sufi principles include unconditional trust in God (tawakkul) and striving to become unstuck (fanāʾ) in God. The sharia as the external system of norms of Islam is contrasted in Sufism with the Tarīqa as a mystical path. Scholars from the eastern Iranian region, such as al-Qushairī, elaborated Suficism in manuals in the 10th and 11th centuries into a comprehensive spiritual doctrinal system. This doctrinal system, with its specific terminology for soul states and mystical experiences, spread to other areas of the Islamic world in the course of the 12th century, became increasingly popular among jurists, theologians, and literati, and became one of the most important points of reference in Muslim religious thought.

Within Sufism, the sheikh or pir has his own model of authority. He guides those who want to tread the spiritual path. The one who joins such a shaykh and submits to his authority is conversely called Murīd (Arab. "the willing one"). People who have reached perfection on the spiritual path are considered "friends of God" Auliyāʾ Allāh. In North and West Africa, they are also called marabouts. The veneration for such individuals has led to the development of a strong veneration of saints in the Sufi environment. The gravesites of God's friends and marabouts are important destinations for local pilgrimages.

From the late Middle Ages, numerous Sufi orders have emerged. Some of them, such as the Naqshbandīya, the Qadiriyya, and the Tijaniyya, have a worldwide following today.

Puritan groups such as the Wahhabis reject the Sufis as heretics. On the one hand, they criticize such practices as dhikr, which in the tradition of Kunta Haji Kishiev and others, for example, is accompanied by music and bodily movements; on the other hand, they criticize Sufi veneration of saints because, in their view, no mediator should stand between man and God. Such conflicts can be found up to the present, for example in the Chechen independence movement. The Sufi Kunta Hajji is also considered one of the models and examples of non-violent traditions and currents in Islam.

Ahmadiyya

→ Main article: Ahmadiyya

The Ahmadiyya emerged in British India at the end of the 19th century as an Islamic movement with a messianic character. Its founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, claimed to be the "Mujaddid (renewer) of the 14th Islamic century," the "Promised Messiah," the Mahdi of the end times expected by Muslims, and a "(subordinate to Muhammad) prophet." The latter point in particular led other Muslims to regard the Ahmadiyya as heretical because, based on Sura 33:40, Muhammad is considered the "Seal of the Prophets." Since the Islamic World League excluded the Ahmadiyya from Islam as an "infidel group" in 1976, there have been attacks on members of this special community in several Islamic countries.

Quranism

→ Main article: Quranism

Quranism is an Islamic current whose adherents regard the Quran alone as the source of faith and reject hadiths as a legal and theological source alongside the Quran. This particular interpretation of the faith leads to certain Quranic understandings deviating significantly from orthodox doctrines.

Within the Muʿtazila, a theologically Islamic current that experienced its heyday between the ninth and eleventh centuries, there were various critical positions regarding the hadiths. One of its representatives, an-Nazzām, had a very skeptical attitude toward the hadiths and examined contradictory traditions regarding their deviant content in order to defend his position.

In 1906, Muhammad Tawfīq Sidqī published a critical article in Rashīd Ridā's journal al-Manār entitled "Islam is the Qur'an alone" (al-Islām huwa al-Qurʾān waḥda-hū). In it, he criticized the Sunnah and argued that Muslims should rely on the Qur'an alone, since the Prophet's conduct had been intended as a model only for the first generations of Muslims. The article, which was the result of discussions with Rashīd Ridā in which Sidqī had put forward his ideas of the temporal limitations of the Sunnah, was met with fierce rejection by contemporary Muslim scholars, and there were several of them who wrote rebuttals to it.

Quranism also acquired a political dimension in the 20th century, when Muammar al-Gaddafi declared the Quran to be the constitution of Libya. Through Egyptian scholars such as Rashad Khalifa, the discoverer of the "Quranic code" (Code 19), a hypothetical mathematical code in the Quran, and Ahmad Subhy Mansour, Islamic scholar and activist who emigrated to the United States, Quranist ideas spread to many other countries as well.

Islamic denominations and schools of law

See also

- The heyday of Islam

- History of Islam in Germany

- Freedom of belief in Islam

- Islamophobia

- Islamism

- Islamist terrorism

- Criticism of Islam

- Liberal Movements in Islam

- Timetable of Islamic dynasties

- List of countries by Muslim population

Articles on Islam in specific regions (selection)

- Islam in Germany

- Islam in Africa

- Islam in Brazil

- Islam in Europe

- Islam in France

- Islam in Italy

- Islam in the Netherlands

- Islam in Austria

- Islam in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus

- Islam in Russia

- Islam in Switzerland

- Islam in the Czech Republic and Slovakia

Questions and Answers

Q: What is Islam?

A: Islam is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion that teaches and believes in the Quran, the holy scripture of Islam. It means submission to the will of God and Muslims view Muhammad as a prophet and messenger of God.

Q: Who are Muslims?

A: Muslims are believers of Islam who submit to the will of God.

Q: What does "Kafir" mean in Islam?

A: Kafir is a term used in Islam to refer to non-Muslims.

Q: How is linguistically defined?

A: Linguistically, Islam is defined as surrender to the command of God without objection, submission, rebellion, or stubbornness.

Q: What do Muslims believe about prophets before Muhammad?

A: Muslims believe that there were many other prophets before Muhammad since dawn of humanity including Adam, Noah (Nuh), Abraham (Ibrahim), Moses (Musa), and Jesus (Isa). They believe all these prophets were given messages by God but Satan made past communities deviate from them.

Q: What groups make up most of Muslim population?

A: Most Muslims belong to one of two groups; Sunni Islam which makes up 75-90% or Shia Islam which makes up 10-20%. There are also other smaller groups like Alevis in Turkey.

Q: How many followers does Islam have worldwide?

A: With about 1.75 billion followers (24% of the world's population),Islam is the second-largest religion in the world and it's also growing rapidly both globally and within Europe specifically.

Search within the encyclopedia