Irish language

![]()

Irish is a redirect to this article. For other meanings, see Irish (disambiguation).

The Irish language (Irish Gaeilge [ˈɡeːlʲɟə] or in the Munster dialect Gaolainn [ˈɡeːləɲ], according to the orthography in use until 1948 usually Gaedhilge), Irish or Irish Gaelic, is one of the three goidelic or Gaelic languages. It is thus closely related to Scottish Gaelic and Manx. The Goidelic languages belong to the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic languages.

According to the 8th article of the Constitution, Irish is "the principal official language" (an phríomhtheanga oifigiúil) of the Republic of Ireland, "being [its] national language". The European Union has listed Irish as one of its 24 official languages since 1 January 2007. Notwithstanding its prominent official status, the language still has few native speakers. Communities in Ireland where Irish is still spoken in daily interaction are officially designated and promoted as Gaeltacht, but even there Irish is not necessarily in majority use.

The language identifier of Irish is ga or gle (according to ISO 639); pgl denotes the archaic Irish of the Ogham inscriptions, sga the subsequent Old Irish (until about 900), and mga Middle Irish (900-1200).

History

The origins of the Irish language are largely obscure. While Irish is indisputably a Celtic language, the way and time it came to Ireland are hotly disputed. All that is certain is that Irish was spoken in Ireland at the time of the Ogam inscriptions (i.e. from the 4th century at the latest). This earliest stage of language is known as Archaic Irish. The language processes that had a formative effect on Old Irish, i.e. apocope, syncope and palatalisation, developed during this period.

It is generally assumed that (Celtic) Irish gradually replaced the language previously spoken in Ireland (of which no direct traces have survived, but which can be traced as a substrate in Irish) and was the sole language on the island until the adoption of Christianity in the 4th and 5th centuries. Contacts with Romanized Britain are demonstrable. A number of Latin loanwords in Irish date from this period, in most of which the regional pronunciation of Latin in Britain can be demonstrated.

Other words arrived in Ireland at the time of the Old Irish (600-900) with the returning peregrini. These were Irish and Scottish monks who mostly proselytized and practiced monastic scholarship on the continent. This scholarship corresponds to the high degree of standardization and dialectlessness of Old Irish, which is very rich in inflections, at least in its written form.

Since the invasions of the Vikings from the end of the 8th century, Irish had to share the island with other languages, but at first only to a small extent. The Scandinavians settled mainly in the coastal towns as traders and gradually assimilated into Irish culture. Scandinavian loanwords were predominantly from seafaring and trade, for example Middle Irish cnar "merchant ship" < Old Norse knørr; Middle Irish mangaire "travelling merchant" < Old Norse mangari. During this period, the language changed from the complicated and largely standardized Old Irish to the grammatically simpler and much more diversified Middle Irish (900-1200). This was reflected, among other things, in the great simplification of inflectional forms (especially in verbs), the loss of the neutral, and the neutralization of unstressed short vowels.

From today's point of view, the invasion of the Normans from 1169 onwards was more decisive for Irish. It is no coincidence that from about 1200 onwards we speak of Early Irish or Classical Irish (until about 1600). Despite the turmoil at the beginning of the period and the continued presence of the Normans in the country, this period is marked by linguistic stability and literary richness. The peripheral areas in the west and north in particular, though mostly tributary, were largely independent politically and especially culturally. As a result, Irish remained by far the most widespread language for the time being; only for administrative purposes was French used until the 14th century; the English of the new settlers was only able to assert itself around Dublin ("The Pale") and Wexford. The Kilkenny Statutes (1366), which prohibited English-born settlers from using Irish, were largely ineffective. The very fact that they had to be introduced is indicative of the language situation at the time: many of the original Norman or English families adopted some or all of the cultural customs of the country. By the end of the 15th century the towns outside the Pale had also become Gaelicised again, and in the course of the 16th century Irish penetrated the Pale as well.

Even the planned settlements of English and Scottish farmers in parts of Ireland in the 16th and 17th centuries did not significantly change the situation for the time being. The lower classes mostly spoke Irish, the upper classes English or Irish. During that period, however, the percentage of Irish speakers in the total population probably began to slowly dwindle. When, as a result of political unrest, the remnants of the old Irish nobility fled the island in 1607 (flight of the earls), the language was completely stripped of its roots in the upper classes. In terms of linguistic history, this is the beginning of New Irish or modern Irish.

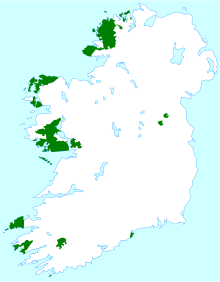

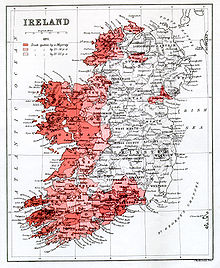

The most decisive factor in the decline of the language in the 19th century was rural hunger. This was widespread and occasionally catastrophic, particularly long and intense during the Great Famine of 1845-1849. Between 1843 and 1851 the number of Irish speakers was reduced by 1.5 million, the majority of whom starved to death, the remainder emigrating. This represents a loss of more than a third, as the total number of Irish speakers at the end of the 18th century is estimated at 3.5 million. Those who wanted to achieve, or in some cases just survive, had to migrate to the cities or abroad (Britain, USA, Canada, Australia) - and speak English. As parents often had to prepare their children for life in the city or abroad, this development gradually backfired on rural areas. Irish became, at least in the public consciousness, the language of the poor, of peasants, fishermen, tramps. The language was now visibly displaced by English. Revival efforts from the late 19th century onwards, and especially from Irish independence in 1922 onwards (with the involvement of the Conradh na Gaeilge, for example), as well as the deliberate promotion of the social status of Irish, were unable to halt, let alone reverse, the trend. Among the negative factors affecting the language situation in the late 20th and 21st centuries are, above all, the increasing mobility of people, the role of the mass media and, in some cases, the lack of close social networks (almost all Irish speakers live in close contact with English speakers). Today, Irish is spoken daily only in small parts of Ireland, and sporadically in the cities. These language islands, mostly scattered over the northwest, west, and south coasts of the island, are collectively called Gaeltacht (also individually so; plural Gaeltachtaí).

The 2006 Irish census found 1.66 million people (40.8% of the population) who claim to know Irish. Of these, 70,000 are native speakers at the highest, but by no means all of them speak Irish on a daily basis and in all situations. According to the 2006 Census, 53,471 Irish people claim to speak Irish daily outside of educational institutions. In the 2016 Census, 1,761,420 Irish people reported being able to speak Irish, representing 39.8% of the country's population. Despite an increasing absolute number of speakers, the percentage in the population decreased slightly. 73,803 reported speaking Irish on a daily basis, of which 20,586 (27.9%) live in the Gaeltachtaí.

In the cities, the number of speakers is increasing, albeit at a still low level. The Irish spoken in the cities, especially by children of second language learners, often differs from the "traditional" Irish of the Gaeltachtaí and is characterised by simplifications in grammar and pronunciation, which impairs mutual understanding. For example, the distinction between hard and soft consonants, which is necessary for the formation of the plural, is neglected, and the plural is accordingly expressed in other ways. Grammar and sentence structure are simplified and partly adapted to English. The extent to which this urban Irish adapts to the standard language or develops as an independent dialect or creole is a matter of debate.

Irish is also cultivated among some descendants of the Irish who emigrated to the United States and other countries. However, mainly due to lack of opportunity, few of them achieve sufficient proficiency to be able to use the language beyond some nostalgically cultivated phrases. More of this learning takes place through relevant websites and also participation in Irish language courses in Ireland.

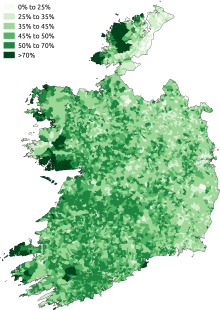

Distribution of Irish in the Republic of Ireland as a first and second language according to the 2011 Census

Current distribution of Irish as a first language (Gaeltacht)

Distribution of Irish after the 1871 Census

Dialects and geographical distribution

→ Main article: Irish dialects

As a mother tongue or first language, Irish exists only in the form of dialects; there is no standard language spoken as a mother tongue (only the orthography is standardized, so that in individual dialects phonetics and spelling can sometimes differ). Irish learners mostly speak Standard Irish (An Caighdeán Oifigiúil, officially valid since 1948), which was developed and taught on government initiative, often mixed with a learned dialect. A distinction is made between the main dialects of Munster, Connacht and Ulster, which can be subdivided into numerous, geographically mostly separate sub-dialects.

Apart from the areas indicated above, there are still two tiny little language islands in County Meath northwest of Dublin (Rath Cairne and Baile Ghib) since the 1950s, which were mainly for experimental purposes: Can Gaeltachtaí persist near a city like Dublin? To this end, Irish speakers from Connemara were settled there and financially supported. By the mid-20th century there were other areas with larger numbers of Irish speakers, including parts of Northern Ireland (Glens of Antrim, West Belfast, South Armagh and Derry) and County Clare.

The individual dialects differ linguistically in many respects:

- Lexic

- "when?": Munster cathain? , cén uair? , Connemara cén uair? , Donegal cá huair?

- Syntax

- "She's a poor woman":

- Standard Is bean bhocht í (is woman poor she), Bean bhocht atá inti (woman poor is in-ihr)

- Munster Is bean bhocht í (is woman poor she), Bean bhocht is ea í (woman poor it is she), Bean bhocht atá inti (woman poor is in-ihr)

- Connacht and Donegal Is bean bhocht í (is woman poor she), Bean bhocht atá inti (woman poor is in-ihr)

- Morphology

- general tendency: the further south and west, the more often synthetic verb forms are used instead of analytical ones: "I will drink" - ólfaidh mé vs. ólfad; "they ate" - d'ith siad vs. d'itheadar

- in Munster there are still remnants of the dative plural in use

- Phonology and phonetics

- in Munster 2nd or 3rd syllables containing long vowels or -ach- are stressed

- Transposition of the "tense" consonants /L/ and /N/ inherited from Old Irish and their palatalized equivalents /L'/ and /N'/, example ceann, "head":

- Donegal and Mayo /k′aN/ (short vowel, tense N).

- Connemara /k′a:N/ (long vowel, tense N).

- West Cork (Munster) /k′aun/ (diphthong, unstressed n).

Questions and Answers

Q: What language is spoken in the Republic of Ireland?

A: Irish, Irish Gaelic, or Gaeilge is a language spoken in the Republic of Ireland.

Q: How is Irish related to other Celtic languages?

A: Irish is a Celtic language and so it is similar to Scottish Gaelic and Manx Gaelic and less so to Breton, Cornish, and Welsh. Many people who speak Irish can understand some Scottish Gaelic but not Welsh because the Celtic languages are divided into two groups. One group is called the p-Celtic languages, and the other is called the q-Celtic languages. Irish and Scottish Gaelic are q-Celtic languages, and Welsh is a p-Celtic language.

Q: What did Queen Elizabeth I attempt to do with regards to learning about Irish?

A: Queen Elizabeth I of England tried to learn Irish, and Christopher Nugent, 9th Baron of Delvin gave her an Irish primer. She also asked her bishops to translate the Bible into Irish in an unsuccessful attempt to split the Catholic people from their clergy.

Q: When did most people stop speaking Irish as their primary language?

A: Until the 19th century, most people in Ireland spoke Irish but that changed after 1801 when Ireland joined Great Britain to form the United Kingdom. Ireland’s state schools then became part of the British system and had to teach or even allow only English. The Catholic Church also began to discourage its use.

Q: Who encouraged people in Ireland not speakIrish?

A: The Catholic Church discouraged its use while Daniel O'Connell (an irish nationalist leader) thought that people should speak English since most job opportunities were in English-speaking countries such as United States or British Empire at that time .

Q: Is it mandatory for schools in Republic of Ireland teach students about this langage?

A: Yes ,it must be taught in all schools in Republic of Ireland .

Q: Where can we find one of newest Gaeltacht areas ? A: The newest Gaeltacht area can be found on Falls Road , Belfast City where whole community now tries using irish as first langage .

Search within the encyclopedia