Iran

Template:Infobox State/Maintenance/TRANSCRIPTION

Template:Infobox State/Maintenance/NAME-German

Iran, also: the Iran (with article), Persian ايران, DMG Īrān, [![]()

![]() ʔiːˈɾɒːn], full form: Islamic Republic of Iran, before 1935 on international level (exonym) also Persia, is a state in the Near East. With about 83 million inhabitants (as of 2019) and an area of 1,648,195 square kilometers, Iran is one of the 20 most populous and largest states on Earth. Capital, largest city and economic-cultural center of Iran is Tehran, other cities with millions of inhabitants are Mashhad, Isfahan, Tabriz, Karaj, Shiraz, Ahvaz and Ghom. Iran has called itself the Islamic Republic since the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

ʔiːˈɾɒːn], full form: Islamic Republic of Iran, before 1935 on international level (exonym) also Persia, is a state in the Near East. With about 83 million inhabitants (as of 2019) and an area of 1,648,195 square kilometers, Iran is one of the 20 most populous and largest states on Earth. Capital, largest city and economic-cultural center of Iran is Tehran, other cities with millions of inhabitants are Mashhad, Isfahan, Tabriz, Karaj, Shiraz, Ahvaz and Ghom. Iran has called itself the Islamic Republic since the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Iran consists largely of high mountains and arid, desert basins. Its location between the Caspian Sea and the Strait of Hormuz on the Persian Gulf makes it an area of high geostrategic importance with a long history dating back to antiquity.

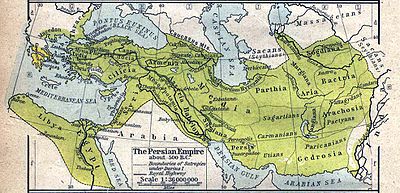

After the empire of Elam was formed between 3200 and 2800 BC, the Iranian Medes united the area into one state for the first time around 625 BC, taking over cultural and political leadership in the region. The Achaemenid dynasty, founded by Cyrus, ruled from southern Iran the largest empire in history to that time. It was destroyed in 330 BC by the troops of Alexander the Great. After Alexander, his successors (Diadochi) divided the empire among themselves until they were replaced by the Parthians in the Iranian region around the middle of the 3rd century BC. These were followed from about 224 AD by the Sassanid Empire, which until the 7th century was one of the most powerful states in the world alongside the Byzantine Empire. After the Islamic expansion spread to Persia, in the course of which Zoroastrianism was replaced by Islam, Persian scholars became the bearers of the Golden Age until the Mongol storm in the 13th century set the country far back in its development.

The Safavids unified the country and made the Twelver Shiite creed the state religion in 1501. Persia's influence dwindled under the Kajar dynasty, founded in 1794; Russia and Great Britain forced the Persians to make territorial and economic concessions. In 1906, a constitutional revolution occurred, resulting in Persia's first parliament and a constitution that provided for separation of powers. It adopted the constitutional monarchy as its form of government. The two monarchs of the Pahlavi dynasty pursued a policy of modernization and secularization. In parallel, the country was occupied by Russian, British and Turkish troops during World War I and by British and Soviet troops during World War II. Thereafter, there were repeated instances of foreign influence, such as the establishment of an Autonomous Republic of Azerbaijan with Soviet assistance or a CIA-organized coup d'état in 1953. The suppression of liberal, communist and Islamic opposition led to multifaceted tensions that culminated in the 1979 revolution and the overthrow of the shah.

Since then, Iran has been a theocratic republic led by Shiite clerics, at the top of which the religious leader concentrates power. He is controlled only by the Council of Experts. Regular elections are held, but they are criticized as undemocratic because of the extensive hemming in by those in power, accusations of manipulation, and the insignificant position of the parliament and the president. The Iranian state controls nearly every aspect of daily life in terms of religious and ideological conformity, permeating the lives of all citizens and curtailing individual freedom. There is no comprehensive freedom of the press or freedom of expression in Iran. Since the Islamic Revolution, good relations with Western states have turned into open hostility, which is also firmly anchored in the state ideology, especially with regard to the formerly friendly United States and Israel. Iran is largely isolated in foreign policy and at the same time a regional power in the Middle East.

In addition to ethnic Persians, Iran is home to numerous other peoples who have their own linguistic and cultural identities. The official language is Persian. The largest ethnic groups after Persians are Azerbaijanis, Kurds and Luri. The peoples of Iran have long traditions in arts and crafts, architecture, music, calligraphy, and poetry; the country is home to numerous UNESCO World Heritage sites.

Thanks to its natural resources, above all the world's largest natural gas reserves and the fourth-largest oil reserves, Iran has a great deal of influence on the world's supply of fossil fuels. Apart from this, the Iranian economy has long been in a deep crisis, partly due to the high proportion of inefficient state-owned enterprises, corruption and the sanctions imposed in the wake of the conflict over Iran's nuclear program.

Country name

From earliest times, the country was called Irān (an abbreviation of Middle Persian Ērān šahr) by its people. The Old Persian form of this name, Aryānam Xšaθra, means "land of the Aryans" (see also Eran (term)).

The term Persia, which was in use in the West until the 21st century, goes back to Pars (or Parsa/Persians; related to "Parsees"), the heartland of the Achaemenids, who created a first Persian empire in the 6th century BC. Called Persis by the Greeks, it essentially referred to the present-day province of Fars around Shiraz. The Persian word Fārsī / فارسی /'Persian' for the Persian language is also derived from it.

In 1935, Shah Reza Chan elevated "Iran" to an official designation.

The geographical term Iran refers to the entire Iranian highlands.

In German, the word occurs both with a definite masculine article ("der Iran") and without an article. The Center for Near and Middle Eastern Studies at the Philipps University of Marburg recommends the spelling without the article, which is also common in German academic language. The German Foreign Office also does not use the article.

Population

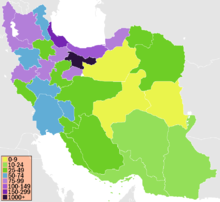

Iran today has a population roughly equal to that of Germany, but spread over a territory four and a half times as large. The average population density is thus 46 inhabitants/km². However, the distribution of inhabitants is very uneven. Areas favored for their environmental conditions have very high population densities, such as the provinces along the Caspian Sea (Gilan and Mazandaran provinces with 177 and 129 inhabitants/km², respectively) or along the Alborz (Tehran and Alborz provinces with 890 and 471 inhabitants/km², respectively). In contrast, the desert-dominated areas are extremely sparsely populated or not populated at all: in Semnan, South Khorasan and Yazd, only 6, 7 and 8 people live per square kilometer, respectively.

Population development

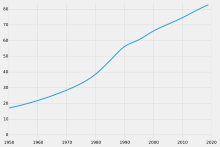

At the beginning of the 20th century, Iran had less than 12 million inhabitants, of whom 25-30% lived nomadically and only 15% in cities. By 1976, the population had grown to 33.7 million. Finally, the last census in 2016 showed just under 80 million people. The urban population had grown to about one-third of the total by 1956 and to nearly half by 1976; by 2011, 70% of all Iranians lived in cities.

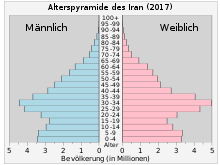

The sharp increase in the population is primarily due to the significant rise in life expectancy: at the beginning of the 20th century, people lived to be just under 30 years old on average and infant mortality was 50%. In 2015, by contrast, average life expectancy was 76.2 years for women and 74.0 years for men. At the same time, fertility remained at a very high level for a long time: in 1956 at an average of 7.9 children per woman, and in 1986 at 6.39 children per woman. It has fallen very sharply since then, and in 2008 it was only 1.81 children per woman. In 2018, fertility was 2.1, which is roughly at the conservation level. The world average in 2018 was 2.42. Only in Japan after World War II can a faster decline in fertility be observed. Due to this, the natural population growth has slowed down, in the period from 2010 to 2013 it was 1.1% per year. This population trend results in an Iranian population that, while still very young on average, is steadily aging. While the average age of Iranians was 22.4 years in 1976, it was already 29.86 years in 2011, thus increasing by about two years per decade. Three quarters of Iranians are under 40 and 55 % of Iranians are under 30.

During the same period, the number of households increased disproportionately, so that the average size of an Iranian household fell from 5 persons in 1976 to only 3.5 persons in 2011.

Migration

It is estimated that about four million Iranian-born people live outside Iran today; in 2010, about 1.3 million Iranian nationals, about 1.7% of the population, lived outside the country. The main destination countries for Iranian emigrants include the United States, Canada, the northern EU countries, Israel, and the rich Persian Gulf littoral states such as Qatar, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates. Since the emigrants include a large number of well-educated young people, the losses to the Iranian economy from emigration appear to be massive: some $50 billion is said to be lost annually to the brain drain. The money flowing back to Iran from exile adds up to about $1.1 billion annually. The Iranian diaspora, which has strong ties to its homeland, is also an important part of the Iranian population's opinion-forming process through Persian-language radio and television stations and blogs.

Iran is also a destination for immigration. The 2011 census showed that nearly 1.7 million foreigners lived in Iran, of whom just under half had arrived as refugees. The majority of foreigners (1.45 million) came from Afghanistan. Afghans have been migrating to Iran for many decades, on the one hand as labor migrants, but increasingly as refugees since the Sovietinvasion and subsequent wars. Since many Afghans speak a variant of Persian and also have a very similar cultural and religious background, it is relatively easy for them to integrate in Iran and to pass themselves off as Persians in censuses; the number of Afghans could thus be significantly higher. Nevertheless, Afghans also face discrimination in Iran. In addition to Afghans, about 50,000 Iraqis and 17,000 Pakistanis live in Iran. Other countries of origin of immigrants are Azerbaijan, Turkey, Armenia and Turkmenistan.

Ethnicities

→ Main article: Ethnic groups in Iran

Iran's mediating position between Central Asia, Asia Minor, Arabia, and the Indian subcontinent has resulted in a high degree of ethnic diversity. Indo-European groups probably migrated into the Iranian highlands from the north and reached the Zagros at the beginning of the first millennium B.C. The Medes were the first Iranian people to establish a stable empire on Iranian territory. After the Arabs conquered Iran, Arabs settled everywhere in the country and mixed with the resident population; many Iranian families can prove their Arab origin by their names. In the 11th century, Turkic tribes began to migrate into what is now Iran in ever new spurts. With their nomadic way of life, they shaped large areas of Iran until the beginning of the 20th century; in the end, they settled mainly in the northwest of the country, where the climate is most suitable for nomadic cattle breeding.

The peoples of Indo-European origin dominate the country numerically today. Between 60 and 65 % of the population count themselves as Persians; the Iranian highlands are populated almost exclusively by Persians. To the west of the Persian settlement area live Kurds, who make up 7 to 10 % of the total population, speak a language related to Persian and largely adhere to Sunni Islam, and the predominantly Shiite Luri (6 % of Iran's population). In eastern Iran live the Baluch, also Sunni, who make up 2% of the population. Smaller Indo-European peoples include the Bakhtiari.

The Turkic-speaking peoples include primarily the mostly Shiite Azerbaijanis (Azeris), who make up 17 to 21% of Iran's population and live in the northwest of the country. The mostly Sunni Turkmen inhabit the northern steppe areas, and there are also numerous islands of Turkic-speaking populations scattered throughout the country, including the Kashgai.

The Arabs of Iran live in the southwest on the border with Iraq; they make up about 2 to 3 % of the total population. Iran is also home to a large number of very small ethnic groups, some of which settled in Iran before the Persians arrived (such as the Assyrians) or came to the country in several waves, some centuries ago (such as the Armenians).

The available figures on the ethnic composition of the Iranian population vary widely because the Iranian state does not compile and publish any data. Last but not least, mixed marriages, which are now normal, have led to a certain blurring of ethnic boundaries. It can be assumed that it is not always possible to classify the original ethnic groups in linguistic terms either, since large parts of the minorities have now been assimilated into the Persian majority culture, especially in terms of language.

Languages

Various languages are spoken in the multi-ethnic state of Iran. The official language is Persian. It belongs to the family of Indo-European languages and thus has no common roots with Arabic, although Persian has absorbed numerous loanwords from Arabic and is written with an alphabet derived from Arabic. Persian is spoken as a first language by only more than half of Iranians; on the Iranian plateau, almost all inhabitants speak Persian. As a native or second language, 85% of Iranians spoke Persian in 2000, another 5% could understand it, and only 10% did not speak it at all. As late as the 1930s, each ethnic group could speak only its own language; recruits drafted into the military therefore had to first learn Persian for six months.

The part of the population whose mother tongue is not Persian is divided into several linguistic groups, living mainly in the periphery, along the borders. Minority languages include those related to Persian, such as Kurdish, Mazandaran, Gilaki, Pashto, Lurish, Bakhtiari, Baluchi, and Tali; overall, about 70% of Iranians speak an Indo-Iranian language. Turkic languages are spoken by approximately 18 to 27% of Iranians, depending on the source, primarily in the northwest and northeast of the country; these include Azerbaijani, but also Turkmen, Kashgai, Khorasan Turkic, and Afshar. The Arabic language is spoken by about 2% of the population in Iran. As the language of the Koran, however, it is learned by all children in school. Since multilingualism is a matter of course among Iranians today, there are very divergent figures on the exact distribution of speakers among the many different languages. Persian dialects spoken in Iran include Bandari and Sistani, as well as Chuzi (in Fars province). Dardic dialects such as Kohestani are also spoken.

The Persian language is established in the Iranian constitution as the sole official and educational language. However, minority languages are allowed to be taught in schools alongside Persian. English is the second foreign language in schools after Arabic.

·

Persian speaking population in Iran

·

Turkic-speaking population in Iran (Azeri, Qashqai, Turkmen, etc.)

·

Kurdish population in Iran (Kurmanji, Sorani, Southern Kurdish and others)

·

Masanderan-speaking population by province

·

Gilaki speaking population in Iran

·

Luren in Iran by province

·

Arab population by province in Iran

·

Baluchi speaking population in Iran

·

Tali-language population by province

Religion

→ Main article: Twelver Shia and Christianity in Iran.

Despite modernization and 50 years of secularization under the Pahlavi, Iran today is a state where religion permeates almost every aspect of social life. The 2011 census found that 99.4% of Iran's citizens are Muslim. It is estimated that 89% to 95% of Iranians subscribe to the state religion of Twelver Shia and the remaining 4% to 10% to Sunni Islam. A 2020 survey by the GAMAAN Institute came to a significantly different conclusion. According to it, 32 % of the Iranian population describe themselves as Shiites, 9 % as atheists, 8 % as Zoroastrians, 7 % as spiritual, 6 % as agnostics and 5 % as Sunnis. Smaller proportions describe themselves as Sufis, Humanists, Christians, Bahais and Jews, and 22 % do not identify with any of these worldviews.

The commitment to Shi'iteism is one of the characteristics that most distinguishes Iran from its neighboring states. Yet the fundamental contents, such as belief in a single, omnipotent and eternal God and in Muhammad as the last of the prophets whom God sent to mankind to deliver his message, are identical among Shiites and Sunnis. The fundamental difference between these two streams of Islam lies in the question of who is legitimized to lead the Islamic community. The Shiites recognize only direct descendants of the Prophet Muhammad as legitimate leaders and refer to them as imams. There lived a total of twelve imams. The central belief of the Twelver Shia is the twelfth Imam, living in obscurity, who would one day return to earth, spread Islam throughout the world, and usher in an era that would precede the end of the world. The Imams and their descendants are greatly revered by the Shiites. Shrines were built around the tombs of these individuals and their relatives, of which there are more than one thousand in Iran. The more significant among these shrines, such as the Imam Reza Shrine or the Shrine of Fatima Masuma, are destinations for pilgrimages; a practice rejected by the Sunnis. Another distinctive feature of the Shiite confession is the permission, called taghiyeh, to conceal one's faith and neglect religious duties if the believer would otherwise face danger. The Sunni confession is especially widespread among ethnic groups living in border areas with neighboring countries, such as the Kurds, Turkmen or Baluchis. The Shiite leadership does not regard Iranian Sunnis as a minority, but as Muslims who have recognized the Shiites' claim to leadership; consequently, only Shiite-run mosques are available in areas with a majority Shiite population.

Religious minorities in today's Iran comprise only very small groups, but they are highly significant from a historical and cultural perspective. The oldest known Iranian religion is Zoroastrianism. It was founded between 1200 and 700 B.C. by Zarathustra; varieties of Zoroastrianism were considered the state religion under the Sassanids and Parthians. Above all, the monotheism and religious dualism (heaven and hell, god and devil), which were innovative for the time, influenced later religions. Some Iranian festivals that are still celebrated today contain Zoroastrian elements, sometimes in syncretic form. The constitution recognizes Zoroastrians as a religious minority; in the 2011 census, more than 25,000 people described themselves as Zoroastrians. Their centers are in Yazd and Kerman, where sacred flames still burn in the fire temples.

Jews have lived in what is now Iran since ancient times; conversely, Iran has a significant place in Jewish history because King Cyrus II facilitated the return of Jewish populations from Babylonian exile. The Jews have been so assimilated over time that they are distinguished from other Iranians only by their religion. The Jewish community, which had about 80,000 members before 1979, has shrunk sharply to about 20,000 members since the Islamic Revolution. This is mainly due to the anti-Zionist policies of the Iranian government, through which Iranian Jews are easily suspected of being Israeli spies.

Christianity in Iran also has a long history; before the Islamization of Iran, many Nestorians migrated to what is now Iran. Today, Iran is home to about 60,000 Assyrian Christians and the descendants of the approximately 300,000 Armenian Christians who were brought to the country under the Safavids; their center is still in Isfahan. There are also Roman Catholic, Anglican, Protestant and other Christian congregations and churches.

Articles 13 and 14 of the Iranian constitution recognize Christianity, Judaism and Zoroastrianism as religious minorities. They stipulate that the Iranian state must treat them fairly and protect their practice of faith, rites and ceremonies. Religious minorities elect their own deputies in parliamentary elections, for whom a minimum number of parliamentary seats are reserved. However, these religious communities are not allowed to engage in activities against Islam or the Islamic Republic. For example, they must observe dress codes in public and may not recruit members among Muslims. Muslims in Iran face the death penalty for apostasy. In practice, all members of religious minorities are subject to subtle forms of discrimination, such as in the choice of jobs in the state-dominated economy, in inheritance law or in testimony. Even higher offices such as ministers, secretaries of state, judges or teachers at regular schools are closed to them.

Bahaism is considered the largest non-Muslim religion in Iran. It emerged from Shiite Islam in the middle of the 19th century, when a founder figure (the Bab) first called himself the gateway to the Twelfth Imam and later the Twelfth Imam himself, developed a lively missionary activity with several followers such as Qurrat al-Ain, and declared Islamic laws abolished. Bahāʾullāh later formed from Babism the Bahaism that is represented internationally today. Since its inception, this religion has been regarded as a heresy and fought against accordingly in many Islamic countries. The persecution intensified in Iran after the Islamic Revolution. Bahaism is officially banned in Iran, and its approximately 300,000 followers thus practice their religion underground, because professing Baha'is are excluded from higher education or work with the state; they also risk arrest and execution.

Zoroastrian Fire Temple, Yazd

Armenian Apostolic Vank Cathedral, Isfahan

Jewish mausoleum of Esther, wife of Xerxes I, and Mordechai , Hamadan

Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque , Isfahan

Population density

Iran population pyramid

Relief with Middle Persian inscriptions (Pahlavi) of Shapur II and Shapur III, Taq-e Bostan, Kermanshah

Population development in millions of inhabitants

History

→ Main article: History of Iran and List of rulers of Iran.

Antiquity and Middle Ages

The present-day territory of Iran encompasses the historical heartland of ancient Persia, which historically extended over a significantly larger area at times. Until the 20th century, Iran was referred to as Persia in international official usage worldwide. Its geographical position between the Caucasus in the north, the Arabian Peninsula in the south, India and China in the east and Mesopotamia and Syria in the west made the country the scene of an eventful history.

In the Persian metropolitan area, Iran's history leads from the empire of the Elamites and the Medes to the Persian empire of the Achaemenids (Cyrus II the Great to Darius III) and via Alexander the Great and the Diadochic empire of the Seleucids to the Parthians and Sassanids.

Spread of Islam

The wars with Byzantium had so weakened the Sassanid state militarily and financially that internal unrest and vulnerability to external enemies were the result. Thus, the empire fell victim to an invasion by the nomadic inhabitants of the Arabian peninsula, of which there had been many before (Islamic expansion): in 637, the Persians lost the battle of Kadesia, and shortly thereafter the capital, Ctesiphon, was lost. The Arabs, united and motivated by the new religion of Islam, thus conquered the entire Sassanid Empire within a short time, and the slow process of Islamization of Iran began. Although non-Muslims were allowed to practice their religion, they had to pay a tax and observe numerous prohibitions; as late as the 13th century, there were large Zoroastrian communities. Unprepared to rule such a large empire, the Arabs adopted Sassanid governmental structures. Unlike other Arab-conquered territories, the Persians therefore succeeded in largely preserving their culture, making Persian a language of Islam alongside Arabic, and contributing significantly to the development of Islam in cultural, political, and intellectual areas.

Despite the Iranians' leading role in Islamic culture, they were initially disadvantaged as Mawālī or even dhimmi. The fourth caliph Ali, who advocated the abolition of this disadvantage, therefore had a particularly large number of supporters among Iranians. This was a significant factor in the dispute over the legitimacy of the Islamic community's claim to leadership and its subsequent breakup into Sunnism and Shiism. Iranian rebels under General Abu Muslim were also decisively involved in the fighting during the overthrow of the Umayyad dynasty in 750 and the subsequent establishment of the Abbasid caliph dynasty in Baghdad, which was strongly oriented toward the Sassanid model. After the power of the caliphs eroded in favor of the Turkic military, several regional dynasties effectively ruled the country in the 9th and 10th centuries, including the Tahirids, the Saffarids and the Bujids, who acted as the Abbassid caliph's protector from 945 onward. Under the Samanids, whose capital was in Bukhara, many Sassanid works were translated into Arabic, which accelerated the incorporation of Iranian ideas into Islam. Under the Samanids, Islam also broke away from its Arab origins and began to become a cosmopolitan religion.

Turkish and Mongol invasions

As early as the 9th and 10th centuries, arm slaves called Mamluks, originating from Turkic peoples of Central Asia, were incorporated into the armies. Beginning with the 11th century, nomads of Turkic peoples migrated and settled on the territory of present-day Iran. They established short-lived empires on their military base along Iranian Samanid lines, having themselves confirmed as Sunnis by the Abbassid Caliph in Baghdad. These ruling houses included the Ghaznavids and the Seljuks. They promoted art, culture, medicine, and science: the works of the important poets Omar Chayyām, Rumi, and Ferdosi fall within this era. After the Seljuk dynasty passed its zenith, the country again disintegrated into several local kingdoms; severe intra-Shiite fighting broke out between the Ismailis and the Twelver Shiites.

In 1219, the Mongols invaded Iran under Genghis Khan, whose army included many Turks. The Mongols destroyed and plundered Iranian cities, the population shrank dramatically, farmland and irrigation systems decayed, and the central powers disintegrated. From 1256 to 1335, Iran was part of the empire of the Ilkhans. After the assassination of the last Ilchan, local kingdoms were again able to form. But only a short time later, the Iranian highlands were again overrun from Central Asia, this time by the troops of Timur, who founded the Timurid dynasty in 1381, which ruled until 1507. Some areas never recovered from the devastation of the Mongol storm. The turmoil of Mongol and Timurid rule contributed to the rise of popular Islam and dervish culture.

Safavids

After an interlude of the Turkmen tribes Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu, who at times dominated the entire Iranian territory, the Safavids succeeded in re-establishing a stable state. They had their origins in a Turkmen dervish order that had attained great wealth and organized its followers militarily (Kizilbash). In 1501, they introduced the Twelver Shia as the state religion; at the latest since the end of the Safavid period, it has represented a unifying bond in the Iranian multiethnic state. The Safavid Empire was in constant conflict with the Ottoman Empire, which was at the zenith of its power in the 16th century. Today's Iraq, with its shrines sacred to the Shiites, was forever eliminated from Iranian territory in the course of this conflict. This period also saw the intensification of diplomatic contacts with European countries and the beginning of maritime trade with Europe in the Persian Gulf. The Safavids reached the peak of power under Shah Abbas I, who replaced the Kizilbash, who were connected to their respective tribes, with an army loyal only to the Shah and made the city of Isfahan his glamorous residence. Contributing to the Safavids' decline was the fact that the army devoured great resources, that Abbas I's successors were for the most part of little ability, and that the Sunni minority was persecuted. Shiite scholars gained significant power under the declining Safavids and began to take an oppositional role to the kingship.

During the Safavid rule, the number of nomads continued to increase, so that the pressure on the sedentary farmers grew and the nomads armed themselves. This military power remained an important factor until the 20th century. The Safavid dynasty was eventually overthrown by an invasion of Afghans. However, the Afghans were driven out by a nomadic leader who had himself crowned Nadir Shah in 1736, made extensive conquests, but was assassinated in 1747. While southern Iran experienced peace and prosperity under the Zand, chaos reigned in the north.

Qajars

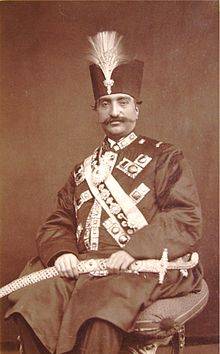

The tribe of the Kajars had originally been settled by Abbas I for border security purposes. They conquered northern Iran, overthrew the Zand, and crowned Agha Mohamed as shah in 1796; however, unlike their predecessor dynasty, the Kajars did not achieve religious legitimization of their power. They also failed to extend their empire to the borders of the Safavid Empire. Already at the beginning of the Kajar period, the conflict with Russia and Great Britain began. By 1828, the Caucasus had been lost to Russia and Russia was given a say in the Iranian succession to the throne. Britain succeeded in making large areas of eastern Iran part of Afghanistan. Faced with this threat situation, initial attempts were made to reform the Iranian state and its military (defensive modernization). These initiatives, which originated with ministers or princes, were not successful, however, due to a lack of money and opposition from conservative dignitaries or the shah himself. At least the first higher educational institution, Dar al-Fonun, was founded and textbooks were translated.

The Constitutional Revolution

The fact that the shah's government was hardly capable of collecting taxes opened the door to the economic influence of European states. This occurred primarily through the granting of concessions that left parts of the economy to foreigners in return for the payment of small fees, such as the development of the telegraph network, fishing rights, the operation of banks or oil exploration from the 1860s onward. The culmination of this development was reached with the tobacco monopoly for a British consortium, which led to a complete boycott of tobacco and the withdrawal of the concession - the first successful movement of merchants, clergy and intellectuals against the rulers. In this environment, the clergy was able to distinguish itself as the guardian of national interests and, under the influence of intellectuals such as Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani, developed a militant Islam. When the Shah wanted to make further concessions to Russia in 1905 in the face of a national bankruptcy, there were months of unrest and a constitutional revolution, as a result of which Iran received its first parliament. It adopted the first constitution on August 5, 1906, which was comprehensively expanded in 1907. It provided for popular sovereignty, fundamental rights and a separation of powers along Western lines, as well as the compatibility of all laws with Sharia law and a supervisory body of five clerics. This constitution remained in force on paper until 1979. Thus, the constitutional revolution ended the absolute monarchy in Iran.

The new form of government, a constitutional monarchy, initially lasted only 15 years; it tended more and more toward chaos and decay and brought neither stability nor progress to the country as a whole. As early as 1908, Mohammed Ali Shah staged a coup and had the parliament fired upon; numerous deputies were arrested and some executed. The civil war, which lasted a year, led to Mohammad Ali's resignation. He was succeeded on the throne by Ahmad Shah, who was initially represented by a regent. Russia and Great Britain had divided the country among themselves into zones of influence and forced the Shah to dismiss the American expert Morgan Shuster, who had been hired to solve the chronic financial shortage. During World War I, despite the declaration of neutrality, fierce battles were fought on Iranian territory between Russia, Great Britain and the Ottoman Empire. After the October Revolution, the Russian army withdrew. However, British plans to make Iran a British protectorate failed. Toward the end of the Kajar dynasty, the Shah's power was limited to the capital. The armed forces consisted only of a Cossack brigade commanded by Russian officers, a paramilitary gendarmerie, and lightly armed fighters from the nomads. The state had no organization to enforce its power and was dependent on large landowners, tribal leaders, and clergy. Between 1917 and 1921, two million people, a quarter of the rural population, died in Iran as a result of war and subsequent epidemics and famine.

Against the backdrop of impending state disintegration, the Cossack Brigade under Reza Khan staged a coup and forced Prime Minister Sepahdar to resign. Reza Khan first became commander-in-chief of the Cossack Brigade, then minister of war under Seyyed Zia al Din Tabatabai, and later Ahmad Qavām as prime minister. In this capacity, he reformed the Iranian military and violently cracked down on several movements with tendencies to secede such as in Tabriz, Mashhad, Mirza Kuchak Khan's Soviet Socialist Republic of Iran, the Bakhtiars, and Kashgai. Strengthened by these successes, Reza Khan became prime minister in 1923. Efforts to make Iran a republic with Reza Khan as its first president, by analogy with the proclamation of the Turkish Republic, failed because of opposition from the clergy. Finally, in late 1925, parliament deposed the last kajar shah and declared Reza Khan Reza Shah Pahlavi. He crowned himself in April 1926.

Pahlavis

Reza Shah was an energetic leader and the first in a long time to tackle real reforms. A modern education system was introduced and the judicial system was reformed. Jurisdiction of foreign powers over their citizens in Iran was abolished. A state monopoly on tea and sugar was created; revenues from this were used to build the Trans-Iranian Railway; roads and other rail lines were also built. Foreign banks were nationalized, and new banks were established. The position of women was improved; Western dress was prescribed for all men except the clergy, and women were forbidden to wear the veil. In 1925, compulsory military service was introduced and enforced, in part by force; thus, against the opposition of the clergy and landowners, all the young men of the country were torn from their traditional careers and underwent a nationalist-secular education. The Law on Identity and Personal Status required all Iranians to use a surname, register with the newly created registration authorities, and carry an identity card; cadjar titles were eliminated without replacement. These two measures set the stage for the imposition of a central state at the expense of local rulers. Reza Shah also began the policy of turning to pre-Islamic Iran, used the crown, cloak and banner in the ancient Iranian model, introduced the Iranian calendar, and from 1935 - not entirely uninfluenced by National Socialist Germany, with which the Shah maintained good relations - demanded that foreign countries call the country Iran ("Land of the Aryans") and no longer Persia. However, Reza Shah ruled dictatorially and retained parliament only to give his rule the appearance of legitimacy and constitutionality. He personally appropriated vast landholdings, instigated the bloody sedentarization of nomads, and eliminated critics and, in the later course of his rule, comrades-in-arms.

Although Reza Shah owed his rise largely to British influence, he did everything he could to curtail Britain's influence on events in Iran. His attempt to position the United States as a counterweight to Britain and the Soviet Union failed. Germany, then under Nazi rule, gladly assumed this role and subsequently became Iran's most important partner. After the outbreak of World War II, Britain demanded that Iran enter the war on the side of the Allies and expel its numerous German advisers, which Reza Shah agreed to only after prolonged hesitation. The Iranian government declared Iran's neutrality and demanded that Britain and the Soviet Union respect this decision. In order to gain access to oil resources and to secure supplies of military material to the Soviet Union via the Trans-Iranian Railway, British and Soviet troops invaded Iran on August 25, 1941, without declaring war (see: Anglo-Soviet Invasion of Iran). Iranian army resistance collapsed after 48 hours. Reza Shah was forced to abdicate. There was no public outcry, and his then 22-year-old son succeeded him on the throne.

The decade that immediately followed these events is known in Iran as the rebirth of constitutionalism. Freedom of expression, freedom of the press and pluralism prevailed as never before in the country. Two significant developments occurred during this period. The Soviet Union, contrary to its commitments, had left its troops in northwestern Iran and supported pro-communist governments in Iranian Azerbaijan and Kurdistan during the Iranian crisis. Only after American pressure did the Soviet Union agree to withdraw and the Iranian army was able to crush the two secessionist states. The second development was the nationalization of the oil industry, which had been demanded since 1941 and was passed by Parliament in 1951. The British government, needing the revenues of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, subsequently organized a boycott of Iranian oil, which led to the Abadan crisis and brought the Iranian state to the brink of bankruptcy. Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, who remains popular to this day and is most identified with nationalization, attempted to curtail the Shah's powers at the same time. By 1953, tensions were at their peak and the Shah fled the country. Mohammad Mossadegh was overthrown a short time later in Operation Ajax with the help of the CIA, and Shah Mohammed Reza subsequently established an autocracy with U.S. support.

Monarchist forces led by General Fazlollah Zahedi arrested Mossadegh. The shah returned to Iran. The government of the day, with Zahedi as prime minister, began new negotiations with an international consortium of oil companies. The negotiations lasted several years. In the end, an agreement was reached that would last until the first oil crisis.

Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (1941-1979) initiated extensive economic, political and social reforms with the "White Revolution" beginning in 1963. Increasing oil revenues made it possible to launch an industrialization program that transformed Iran from a developing country into an up-and-coming industrial state in just a few years. Active and passive women's suffrage were introduced in September 1963. Industrialization and social modernization led to tensions with conservative sections of the Shiite clergy from the beginning. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in particular spoke out against the reform program as early as 1963. Alongside the Islamic opposition, the Fedajin-e Islam, a left-wing guerrilla movement formed in Iran that wanted to change the country with "armed struggle." The political liberalization that began in 1977 enabled the opposition to organize. Violent demonstrations, assassinations and arson attacks occurred, shaking the country to its foundations. After the Guadeloupe Conference in January 1979, at which French President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, President Jimmy Carter of the United States, Prime Minister James Callaghan of the United Kingdom and German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt decided to stop supporting the Shah and to seek talks with Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi left Iran. The Islamic Revolution had begun.

Islamic Revolution and Republic

→ Main article: "Islamic Republic" in the article History of Iran

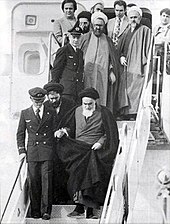

On February 1, 1979, RuhollahKhomeini returned from exile in France; since then, this day has been celebrated as a state commemoration called Fajr (Dawn). He quickly established himself as the supreme political authority and began to form an "Islamic Republic" out of the former constitutional monarchy, among other things by successively and violently eliminating all other revolutionary groups. His policies were characterized by an anti-Western line and did not shy away from terror and mass executions. This led to a rift with numerous former supporters, including his designated successor, Grand Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri.

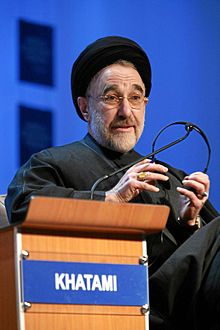

From 1980 to 1988, Iran was in the First Gulf War after Iraq attacked. Iran's prolonged international isolation loosened temporarily in the late 1990s. With Mohammad Chātami's surprising victory in the 1997 presidential elections, the political movement of Islamic reformers established itself in the Iranian parliament. At the beginning of his term, Chātami succeeded in liberalizing the national press. This gave voices critical of the system a public organ to lend weight to their desire for reform.

The revival of press freedom did not last very long. The Guardian Council reversed the laws, citing their incompatibility with Islam, and from then on blocked nearly all of Parliament's attempts at reform. Since then, reformers have faced major losses of confidence among the reform-minded segments of the population. Disappointment over Parliament's impotence led to a very low voter turnout in the 2003 local elections (national average 36 %, in Tehran 25 %) and a clear victory for the conservative forces.

Presidency of Ahmadinejad

The presidential election on June 17, 2005, marked a turning point, especially since Chātami was not allowed to run again after two terms in office. The election of the conservative Mahmud Ahmadinejad as president and his confrontational foreign and repressive domestic policies increased international isolation once again. In particular, his reelection in 2009, which was accompanied by numerous accusations of manipulation, led to massive protests in the country that continued to grow, especially toward the end of 2009, despite violent suppression of even peaceful demonstrations. Ahmadineshād, who was close to the people and distributed subsidies, also came into conflict with even more radical, radical Orthodox religious groups around the influential, eschatological clergymen Jannati, Yazdi and Ahmad Khatami, who succeeded several times-including with the help of Parliament-in forcing Ahmadineshād's ministers and confidants to resign. Other ministers remained in office against the will of the president with the support of radical Orthodox circles, but they were unable to dismiss their Ahmadineshād-backed secretaries of state. The clerics accused Ahmadineshād of pursuing a national Islamic course, rather than an Islamic course. Students of these orthodox clerics (Haghani School in Ghom) occupy numerous key positions in the Iranian military and intelligence services.

The result of the conflicts were threats against Ahmadinejād and the radicalization of the judiciary, executive and legislative branches. In 2011, for example, members of parliament called for the deaths of opposition candidates Mussawi and Karrubi, who were also loyal to the system and had lost the 2009 presidential elections; both were placed under officially unacknowledged and illegal house arrest along with their wives, which was sharply criticized worldwide. Former President Rafsanjāni, who was loyal to the system, lost the influential post of chairman of the Council of Experts to an aged Haghani representative. The confidants and children of the billionaire formerly known as the "Richelieu of the Iranian Revolution" became the object of mobbing, violent Basij-e Mostaz'afin riots in the streets.

Another result of this radicalization was increasing international economic and political isolation, as a result of which private assets were frozen and travel bans and other sanctions were imposed on numerous high-ranking Iranian military officers, police officers, judges, and prosecutors, among others, by the European Community in April 2011.

Presidency Rohanis

On April 11, 2013, Hassan Rohani, considered moderate by Iranian standards and politically close to former President Rafsanjani, announced his candidacy for the June 2013 presidential election. Among other things, he expressed his intention to introduce a civil rights charter, rebuild the economy, and improve cooperation with the world community, in other words, in particular, to overcome Iran's isolation and the sanctions that led to a devastating economic crisis due to the dispute over Iran's nuclear program. During the election campaign, Rohani vehemently defended his actions as chief negotiator, insisting in a TV interview that even under his leadership in the negotiations, there had never been a halt to the nuclear program; rather, the expansion of Iran's nuclear program had been successfully advanced. "Prudence and hope" is the motto of the government he wants to form, he said. According to preliminary data from the Interior Ministry, Rohani won the election in the first round with 18,613,329 votes (50.71%).

Shortly before Rohani visited the UN General Assembly in New York on September 25, 2013, he and supreme religious and political leader Ali Khamenei announced that the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, which has close ties to Ahmadinejād, should stay out of politics in the future. In addition, around September 18, 2013, about a dozen political prisoners were released from prison early, including human rights activist Nasrin Sotudeh. Some observers saw this as Rohani's first attempt to implement his election promise to allow more political freedoms in Iran in the future, but at the same time as a signal for the relaxation of relations with Western countries that Iran had hoped for. Indeed, Rohani achieved the initiation of direct talks between the United States and Iran regarding the nuclear dispute. Others, such as Human Rights Watch, welcomed the releases but saw them as little more than a symbolic gesture, as hundreds of political prisoners continued to sit in Iranian jails. He also said the regime must ensure that those released do not become targets of the security forces and the judiciary again. Iranian Nobel Peace Prize laureate Shirin Ebadi and Amnesty International also sharply criticized Rohani's human rights record and the sharp increase in the number of executions.

Although Rohani did not display the excessive anti-Israel rhetoric of his predecessor, he did not change the content. Thus, on the occasion of al-Quds Day 2014, he declared that there could be no diplomatic way out for the Palestinians, but only that of resistance: "What the Zionists are doing in Gaza (Operation Protective Edge) is an inhumane genocide, so today the Islamic world must uniformly declare its hatred and resistance against Israel." In addition, during a panel discussion at the 44th Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum, he denied follow-up questions from WEF founder Klaus Schwab about whether he would also seek friendly relations with Israel, which has not yet been recognized by the Islamic Republic of Iran. His emphasis on peaceful uses of nuclear power and his offer to mediate in the Syrian civil war, in which Iran is involved on the side of Bashar al-Assad, also drew international attention in mid-September 2013. Critical voices noted that Rohani was acting "as if he were a neutral observer," although Iran has long been a party to the war.

With the conclusion of the Iran nuclear deal on July 14, 2015, with the UN veto powers and Germany, the Iranian leadership achieved Iran's exit from its international isolation and, with the Vienna agreement on January 16, 2016, the lifting of international sanctions. Iran, as well as Western business representatives, expected this to result in a significant growth spurt for their countries.

Rohani was re-elected in the presidential election on May 19, 2017.

In May 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump terminated the nuclear agreement with Iran and announced new sanctions. The move was criticized by the EU, Russia and China. In response, Iran gradually withdrew from the agreement and resumed uranium enrichment in 2019.

A two-week unrest in November 2019 (the most violent riots since 1979) over a drastic gasoline price hike killed about 1,500 people, according to Iranian Interior Ministry insiders, as the state violently quelled the protests. Earlier, Amnesty International reported several hundred deaths from the protests. The Iranian government dismissed Amnesty's claims as baseless. The Internet in the country was at least partially blocked for several days during the riots by government order to prevent the dissemination of information about the protests.

As a result of the targeted killing by U.S. forces of Qasem Soleimani in Iraq at the beginning of 2020, there was a state mourning lasting several days and several funeral marches with up to more than one million participants. This included a mass panic at a funeral procession in Kerman with about 40 dead and several hundred injured.

_(Cropped).jpg)

Hassan Rohani, 2017

Nāser ad-Din Shāh (ca. 1870), the most important shah of the Kajar dynasty

Large demonstration in Tehran on June 17, 2009

Mohammad Chātami

Khomeini's arrival on February 1, 1979

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and Farah Pahlavi, 1977

.svg.png)

Flag of Iran during the Pahlavi period, used today by the opposition

The Persian Empire around 500 B.C.

Celebrating the presidential election in Iran 2017

Safavid Empire and territorial losses

Reza Shah Pahlavi

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the official name of Iran?

A: The official name of Iran is the Islamic Republic of Iran (Persian: ايران).

Q: What region is Iran part of?

A: Iran is part of the Middle East region.

Q: What countries does Iran share borders with?

A: Iran shares borders with Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Iraq, Pakistan, Turkey, and Turkmenistan.

Q: What city is the capital and biggest city in Iran?

A: Tehran is the capital and biggest city in Iran.

Q: How many people live in Iran?

A: There are more than 84.9 million people living in Iran.

Q: When did Iran become a member of the United Nations?

A:Iran has been a member of the United Nations since 1945.

Q: Is it an Islamic republic?

A Yes, it is an Islamic republic.

Search within the encyclopedia