Invasion of Poland

Invasion of Poland 1939

Part of: World War II

The cadet training ship Schleswig-Holstein during the shelling of the Westerplatte in the harbor of Gdansk at the beginning of the Second World War.

Invasion of Poland/Polish campaign

Gdansk - Westerplatte - Tuchel Heath - Krojanten - Mlawa - Radom - Wizna - Bzura - Brześć - Lviv - Rawa Ruska - Lublin - Kampinos Heath - Warsaw - Szack - Modlin - Hel Peninsula - Kock

The invasion of Poland (also known as the Polish campaign) is the name given to the war of aggression waged by the National Socialist German Reich against the Second Polish Republic in violation of international law, with which Adolf Hitler unleashed World War II in Europe. German forces attacked unprovoked on September 1, 1939, supported by Slovak troops, immediately after the alleged and justification invasion of Gliwice.

On September 3, 1939, France and Great Britain declared war on Germany as part of their mutual assistance treaties with Poland. However, their limited military actions, such as the Saar Offensive, were not effective in relieving Poland. Supported by air strikes, two German army groups advanced on Polish territory from the north and south, respectively. German troops reached Warsaw on September 8, which surrendered on September 28.

After three Soviet armies invaded eastern Poland from September 17 in accordance with the secret Additional Protocol to the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, the Polish government fled to neutral Romania on September 17-18, 1939, where it was interned. The Polish government-in-exile, formed on September 30, tried to organize resistance against the occupiers with fled units. The last remaining units of the Polish armed forces in Poland surrendered on October 6, 1939; most of the Polish soldiers went into captivity.

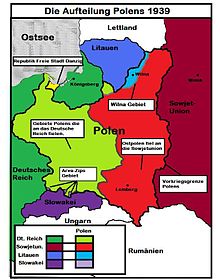

In the German-Soviet Border and Friendship Treaty of September 28, 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union divided Poland between themselves ("Fourth Partition of Poland"). Western Poland, central Poland with the exception of the Białystok voivodeship, and the western parts of southern Poland fell to Germany, and the eastern Polish territories to the Soviet Union. By a decree of October 8, 1939, Hitler separated part of the German-occupied territories, including purely Polish ones, as "incorporated eastern territories" (Reichsgaue Posen and West Prussia) from the so-called Polish residual state and extended the province of Silesia in a southerly direction to include areas populated entirely by Poles. The Free City of Danzig had already become part of the German Reich again on September 1. In the remaining German-occupied areas, the so-called Generalgouvernement was created four days later as a zone of "encapsulation" and lawless exploitation.

While a process of "reorganization" and Germanization was begun in the incorporated eastern territories, the Generalgouvernement was intended for the ruthless exploitation of Poles and Jews and became the target of "völkisch extermination measures". Already during the hostilities as well as the German occupation of Poland 1939-1945, Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the SD and members of the Wehrmacht committed mass murders of Polish intellectuals, priests, trade unionists, aristocrats and Jews, sometimes in a planned manner, sometimes spontaneously. This is considered the "prelude to the German Reich's war of extermination" against the Soviet Union and to the Holocaust.

The term invasion of Poland sometimes refers only to the beginning of the war. The entire course of the war, optionally including the Soviet invasion, was often referred to as the Polish campaign, especially earlier. In Poland, this September campaign (Kampania wrześniowa) or defensive war of 1939 (Wojna obronna 1939 roku) is called.

Political history

→ Main article: Prehistory of the Second World War in Europe

Poland had ceased to exist as an independent state after the three partitions of Poland between Russia, Prussia, and Austria from 1795 until World War I, with an interlude as Congress Poland, which was linked to Russia and ultimately became a mere Russian province as Vistula Land. After the conquest of the area by the Central Powers, the Regency Kingdom of Poland, dependent on them, was established in 1916. As a result of the German defeat, it became the basis for the independent Second Polish Republic proclaimed on November 11, 1918.

Germany and Poland (1918-1933)

Poland was granted part of Pomerelia as access to the Baltic Sea in the Versailles Peace Treaty in January 1920 (Polish Corridor). Gdansk was declared a Free City under the mandate of the League of Nations. After uprisings and a referendum in Upper Silesia, Eastern Upper Silesia also became part of Poland in 1922. In the territories ceded to Poland by Germany, Poles were in the majority. However, Germans also lived everywhere, a total of 1.1 million of the approximately three million inhabitants. Protective rules were provided for the ethnic minorities in Poland - mainly Ukrainians, Jews, White Russians and Germans.

All governments of the Weimar Republic sought a revision of the eastern borders by political means in order to regain the territories lost in 1919 (treaty revisionism). Germany reached an understanding with France in 1925 with the Locarno Treaties, which reduced the importance of Poland for the French security system, while Great Britain made it clear that it did not want to guarantee the Polish Corridor. Germany hoped to be able to force a Poland that was isolated in foreign policy and weakened in domestic politics to recognize German wishes for revision with Soviet support.

By resolution of September 24, 1927, the League of Nations, which Germany had joined in 1926, declared aggressive war to be an international crime and the duty to settle disputes peacefully to be a principle. The Briand-Kellogg Pact of August 27, 1928, which Germany also signed, declared an international ban on aggressive war.

Hitler's Change of Course in Ostpolitik

Since its founding, the NSDAP had been one of the fiercest opponents of the Treaty of Versailles of June 28, 1919. Adolf Hitler also declared the acquisition of "Lebensraum im Osten" (living space in the East) to be the decisive political goal for him in his programmatic pamphlet Mein Kampf. However, a specific hatred of Poland is not to be found in Hitler's political thinking in the early 1920s, but rather an extreme anti-Semitism directed against the Soviet regime as representative of a Jewish Bolshevism. In those years, the German Reich and the Soviets sought a policy of reconciliation and cooperation with the 1922 Treaty of Rapallo and the 1926 Treaty of Berlin, primarily to break the international isolation on both sides.

With the German-Polish non-aggression pact of January 26, 1934, which was limited to ten years, Hitler made an about-face in German Ostpolitik and ended the special German-Soviet relationship. With Poland autocratically ruled and also revisionist, he proceeded to pursue anti-Soviet policies and army buildup in order to conquer "Lebensraum in the East" after, in Hitler's words, "short[ly] decisive blow[s] to the West." Hitler's change of course in foreign policy has been evaluated differently. According to historian Gottfried Schramm, Hitler was "the first politician of the German [sic] Reich to set in motion a sensible policy toward Poland and to show at once how profitable it was to veer from the previous course." For Gerhard L. Weinberg, Hitler pursued rather long-term goals of conquest, for which he set aside short-term revisionism when it stood in the way of his long-term plans. According to a recent study, it was not just a deceptive maneuver by Hitler, but serious attempts to improve relations between the two countries.

In the following years, the Polish-French alliance disintegrated under the impact of the new alliance constellations. The French-Soviet mutual assistance pact of May 2, 1935, further distanced the former partners from each other, while Poland and the German Reich worked more closely together politically and economically. This became particularly evident after the Munich Agreement of September 30, 1938: If the Polish government had still sharply distanced itself from the German occupation of the Rhineland (March 7, 1936), it now exploited the situation for its own interests. On October 2 and 3, Poland occupied the Czech part of the town formerly called Teschen (Český Těšín), which had been separated in 1919, as well as the Olsa region. On October 10, 1938, the Germans occupied the Sudetenland in accordance with the Munich Agreement.

German-Polish negotiations

On October 24, 1938, German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop began negotiations with the Polish government to "resolve all disputed issues." He demanded the reintegration of Danzig into the German Reich as well as transit traffic via a newly built exterritorial section of the Reichsautobahn Berlin-Königsberg and via the railroad (former Prussian Eastern Railway) through the Polish corridor. In return, he offered recognition of the remaining German-Polish borders, an extension of the German-Polish non-aggression pact to 25 years, and a free port of any size in Danzig. These offers were accompanied by a request to join the Anti-Comintern Pact.

The Polish side delayed the answers for almost six months, did not respond to most of the offers from Berlin, and held out the prospect of only gradual changes. It feared that accepting the demands would have turned Poland into a German satellite state. Foreign Minister Józef Beck, on the other hand, aspired to Poland's leading role in a "Third Europe" stretching from the Baltic to the Adriatic. His government therefore rejected a military alliance with Germany directed against the Soviet Union, although the USSR was still regarded in Poland as "Enemy No. 1." The Polish government, however, expected more rapid foreign policy successes from a loose affiliation with the German Reich, rather than full integration into its ideas of alliance, which would ultimately have led to entry into the Anti-Comintern Pact, with which Poland would have irresponsibly exposed itself to the Soviet Union and, moreover, would have effectively dropped out of the Western alliance system. According to Klaus Hildebrand, Ribbentrop's offer was an "unacceptable imposition" for Poland because, if accepted, it would have completely isolated itself from its previous ally France. The country would thus have been "in the future on the chain of the Reich" and would have become a "satrap for a campaign of conquest in the East." The German-Polish negotiations therefore dragged on without result.

Hitler's breach of the Munich Agreement and further territorial gains

On March 15-16, 1939, the Wehrmacht invaded the Czech territories of Bohemia and Moravia, which remained with the Czechoslovak Republic, during the "destruction of the rest of Czechoslovakia" in violation of the Munich Agreement. They were incorporated into the Reich as a formally autonomous "Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia." On March 18, 1939, the German Reich imposed the German-Slovak Protection Treaty on Slovakia, which had thus just become sovereign by Hitler's grace. As a result, Slovakia was included as a de facto satellite state in the forthcoming struggle against Poland (and later against the Soviet Union). It finally participated in the attack on Poland in September with the self-interest of regaining the Slovak border areas lost to Poland after the First World War.

In response to the German ultimatum to Lithuania of March 20, the Lithuanian government returned on March 22 the Memelland, which had been separated from the German Reich in 1920, placed under French administration as a League of Nations mandate, and finally annexed by Lithuania in 1923. The Memel area (about 2600 square kilometers in size) again became part of the province of East Prussia. The German Reich, with the threat of invasion, received back another of the territories it had renounced in the Treaty of Versailles. The disputed corridor including Danzig, of essential importance for relations with the Republic of Poland, was still outstanding, however; the threat to Poland was thus obvious.

The road to war

On March 26, 1939, Poland's government finally rejected the German offer and made it clear that it would treat any unilateral territorial change as a reason for war. As early as March 23, it initiated a partial mobilization of its armed forces to counter a German hand-to-hand occupation of Danzig. This move by Warsaw, however, was criticized in the first Polish analyses of the outbreak of World War II as premature, since the British and French allies were not yet prepared for a military confrontation with the Wehrmacht.

Great Britain ended its previous appeasement policy after the German breach of the Munich Agreement and the now obvious, aggressively conquest-oriented policy of the Third Reich. On March 31, British Prime Minister Arthur Neville Chamberlain assured Poland of military support if its existence was threatened (→ British-French guarantee declaration). At Poland's request, negotiations on a formal mutual assistance pact between the two states began on April 6. On May 17, the Polish-French alliance was renewed by a military agreement. In it, France committed itself to immediate air strikes against Germany in the event of a German attack against Poland, limited offensive strikes from the third day, and a major offensive from the 15th day. In April and May, Poland sought to obtain credit from Britain and France for the purchase of arms and raw materials. But the latter refused. It was not until July 24 that the British government granted a loan of only 8 million pounds. This left Poland to rely on itself.

Hitler denounced the German-Polish nonaggression pact and the Anglo-German naval agreement of June 18, 1935, on April 28, 1939, and had already issued instructions to the Wehrmacht to draw up a war plan against Poland on April 11. In his speech to the Commanders-in-Chief on May 23, 1939, he announced the real objective of the upcoming campaign:

"Gdansk is not the object at stake. For us, it is about rounding out the living space in the east and ensuring food ... In Europe, no other possibility can be seen."

In this way, Hitler wanted to reduce dependence on Western imports (see also: autarky) and avoid a naval blockade, which had contributed to Germany's military and political defeat in the First World War. He continued negotiations over Danzig until August 1939 in order to gain time for war preparations and, if possible, to keep Great Britain and France from military intervention.

The latter could have helped Poland by invading Germany from the west, but they were not prepared or not willing to do so, despite the numerical superiority of their divisions. In order to be able to provide Poland with effective military support on its territory, the Western powers had been negotiating a military convention with the USSR since the summer of 1939. The latter demanded a right of passage for the Red Army through Poland. The latter's government feared that the Soviets would exploit this right to regain the territories they had lost in 1921. Poland's foreign minister therefore finally rejected this condition on August 15, 1939. While these talks were still in progress, the Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov negotiated the German-Soviet Economic Treaty with Ribbentrop in Moscow, which was to secure raw material supplies for the German Reich even in the event of a naval blockade.

In Hitler's address to the Commanders-in-Chief at the Berghof on August 22, 1939, of which several records exist, he defined the goal of the forthcoming campaign as: "Destruction of Poland = elimination of its living strength". The campaign would not entail any major problems with the Western powers: "He did not expect England and France to intervene, but was rather convinced that both states would threaten, rattle their sabers, impose sanctions, perhaps even set up a blockade, but would never intervene militarily. " To contain Germany, they had hitherto hoped for an alliance with the Soviet Union - "I have now knocked that card out of their hands, too."

On August 24, 1939, the Hitler-Stalin Pact followed, whose "Secret Additional Protocol" divided the spheres of interest: According to it, Eastern Poland and the Baltic States were to be added to the Soviet sphere of interest. According to a diplomatically negotiated supplement to this, the rivers Pissa, Narew, Vistula and San were to form the border between the spheres of interest of Germany and the USSR.

While the Hitler-Stalin Pact was still in the making, Great Britain had let Hitler know that nothing would change in her promise of assistance to Poland. Poland, which had always distrusted the Soviet Union, did not believe that anything significant had changed, and accordingly did not believe that the Soviet Union could enter into a war. In order not to give Poland time to mobilize, Hitler was determined to dispense with the formalities of an ultimatum and a declaration of war. Already on August 23, the time of the attack had been set for August 26, 4:30. On the evening of August 25, however, news reached Hitler from Mussolini that Italy was not sufficiently prepared for war. As a result, Hitler ordered a halt to the attack, which had already begun. He saw in the British government's willingness to negotiate an opportunity to isolate Poland and create a pretext for the attack. On August 29, he demanded to the British ambassador, Nevile Henderson, Danzig, the corridor and the protection of German minorities in Poland. Within 24 hours, a Polish emissary with comprehensive powers was to appear in Berlin. The deadline was deliberately too tight in order to increase pressure. Poland had ordered general mobilization in view of the reports from Germany that day, but had postponed the announcement decided upon by the Council of Ministers on British and French advice. Foreign Minister Ribbentrop declared on August 30 that the Poles were not prepared to negotiate and that German proposals were therefore futile. The following day, sixteen points were read out on German radio which Poland claimed to have rejected but which had also never been communicated to Poland. By this time, Hitler had already given the order to attack on September 1.

Propaganda and Fake Border Incidents

As the situation worsened, reports of border violations and incidents had increased on both sides. Since the beginning of 1939, there had been outrages against ethnic Germans in Poland. Nazi propaganda, which was not allowed to report negatively about Poland during the period of the German-Polish non-aggression pact, used these incidents from March 1939 to reinforce an enemy image of Poland. German police reports, for example, described Polish strafing of military and civilian aircraft and numerous assaults, including fatalities, on the German side. The Poles also made a tally of incidents.

Around August 10, 1939, preparations began for the raid on the Gliwice radio station and for other fictitious border incidents under the direction of Reinhard Heydrich and supported by the head of the Gestapo Heinrich Müller. Beginning on August 22, 1939, SD and SS members disguised as Polish irregulars and coerced concentration camp inmates (who were murdered and left lying around as evidence of fighting) faked several "border incidents." On August 31, 1939, a group of SS men led by Sturmbannführer Alfred Naujocks raided the Gleiwitz radio station to fake a Polish raid as a pretext for the criminal war of aggression against Poland. In his Reichstag speech on September 1, Hitler spoke of 14 border incidents that Poland had provoked the previous night, "including three quite serious ones": he was referring to these self-ordered incursions. However, since the SD had carried out its actions amateurishly, they were no longer mentioned in the propaganda after Hitler's speech. German newsreels from September 1939 showed burning German farms in the Polish corridor or the funeral of a shot Danzig SS man as justifications for the war.

Organizers of the raid on the Gleiwitz transmitter : Heydrich and Naujocks, April 11, 1934

Stalin and Ribbentrop's handshake after the signing of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, Moscow, August 24, 1939.

Nevile Henderson (August 1939)

Concomitants and consequences

Hitler's Visits to the Front as "First Soldier of the Reich

Hitler had left Berlin on September 3, 1939, and undertook a series of so-called front-line visits during the Polish campaign, during which he was heavily secured by a military column. On these occasions, he presented himself as particularly close to the soldiers, visiting field kitchens and eating with ordinary soldiers. These casual encounters were part of the new propaganda role as "first soldier," in which Hitler wanted to be seen as a "comrade among comrades" and supposedly shared the fate and also the dangers of average soldiers, following the example of Frederick the Great in the Seven Years' War. Accordingly, in the preceding Reichstag speech of September 1, 1939, he had also described himself as a "first soldier," donned a field-gray uniform, and made succession arrangements in the event of his death. Since Hitler at the same time also staged himself as a field commander, albeit not nearly as intensively as from the French campaign onward, propaganda also picked up on meetings with leading generals during Hitler's trips to the front, showed him taking down the march of soldiers past important bridges that had just been captured, and tried to construct a connection between his trips to the front to alleged hot spots of the fighting and military successes. In fact, however, Hitler's role as commander-in-chief of the Wehrmacht in the Polish campaign was still rather nominal and his interventions in the military command marginal. Far exaggerated, therefore, is the portrayal in Otto Dietrich's book Auf den Straßen des Sieges (On the Roads to Victory, 1939), which, as a directly commissioned work by Hitler, glorifies the Führer's headquarters in Hitler's special train as well as his front-line journeys.

War dead, prisoners, losses

How many Polish civilians lost their lives in the German war of aggression is unknown. It is estimated that 66,000 to 100,000 Polish soldiers fell and about 133,000 were wounded. More than 400,000 Polish soldiers, including about 16,000 officers, fell into German captivity. In addition, there were about 200,000 civilians captured as "suspicious elements." About 61,000 Jews were immediately separated from the rest of the Polish prisoners of war and treated worse. About 100,000 Polish soldiers managed to escape abroad.

There are also no definitive figures for German losses. Hitler spoke on October 6, 1939, of 10,572 dead, 3,409 missing, and 30,322 wounded by September 30. Of these, the Luftwaffe accounted for 734 soldiers. These figures were based primarily on data from the Sanitary Inspectorate, which had recorded 10,244 fallen soldiers and 593 fallen officers during the campaign. Like the entries in the war diaries, they were compiled in direct connection with the fighting. The war diaries gave 14,188 soldiers and 759 officers as war dead of the Wehrmacht. After years of research, the Wehrersatzdienststelle or Wehrmacht Losses Department concluded in 1944 that 15,450 German Army soldiers, including 819 officers, had been killed by enemy action.

According to Norman Davies (2006), the Polish Abwehr inflicted losses of over 50,000 men on the Wehrmacht.

The Wehrmacht's material losses were considerable. Most divisions, for example, reported the loss of up to 50 percent of their vehicle stocks, the majority due to wear and tear in the rough Polish terrain. Some of the motorized divisions were not fully operational again until the spring of 1940. While all Polish military aircraft were lost, with about 140 escaping abroad, German losses amounted to 564 aircraft, or about a quarter of the total; of these, about half were total losses.

Mass murders

Even during the Polish campaign, the Nazi regime began targeted mass shootings of Polish civilians. Five of the six Einsatzgruppen of the Security Policeand the SD set up by Heinrich Himmler for this purpose accompanied the five armies of the Wehrmacht; the sixth group was active in Posen. Their mission was to "combat all elements hostile to the Reich and the Germans in the rear of the fighting troops" and to "destroy the Polish intelligentsia" to a large extent. According to secretly prepared wanted lists (Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen), they murdered about 60,000 Polish citizens by the end of 1939: among them teachers, doctors, lawyers, professors, Catholic priests and bishops, as well as representatives of parties and unions of the Polish labor movement.

About 7000 Polish Jews also fell victim to these massacres. They were murdered not only as members of Polish elites, but also indiscriminately in order to expel the survivors to the Soviet sphere of power. Less known are murders of patients of psychiatric institutions, first in Kocborowo on September 22. They are considered a precursor to the euthanasia murders that began in Germany in January 1940. In addition, the "Volksdeutsche Selbstschutz," a militia that later became part of the SS and consisted mainly of Germans living in Poland, carried out mass murders of Poles as "revenge" for pre-war Polish attacks on "Volksdeutsche." Members of the Wehrmacht, the Danzig Home Guard, the SD and the SS were involved.

At that time, the collaboration of the perpetrator groups was usually not yet centrally directed and coordinated, but it was ideologically intended and laid out in the National Socialist worldview. Even before the war began, Hitler had signaled to his army commanders that he was aiming for the "physical annihilation" of the Polish population and wanted to have tens of thousands of representatives of Poland's intellectual, social and political elite murdered. German soldiers were indoctrinated to view Polish civilians as "subhumans" and Jews as Eastern barbarians. Hitler wanted to "Germanize" the conquered Polish territories as quickly as possible, assimilating "racially valuable" Poles. The Slavic Poles, on the other hand, were to be grouped together in the Generalgouvernement and, with strict racial demarcation, become uneducated forced laborers for the Germans.

War Crimes

By the end of the military administration on October 25, 1939, 16,376 people had been shot in Poland in 714 actions, according to Polish investigations based mostly on eyewitness accounts. Soldiers of the Wehrmacht committed about 60 percent of the attacks against the population. Away from the fighting, more than 3,000 Polish soldiers were murdered by German soldiers who were denied the right to resist the German invaders and were denied combatant status, such as in the Ciepielów massacre. According to many reports, Jewish soldiers in particular were segregated and murdered on the spot immediately after their capture or systematically segregated and treated worse in the POW camps in accordance with an order issued by the OKW on February 16, 1939. In Volhynia, the Wehrmacht mistreated Jews and set fire to synagogues in September 1939. These were war crimes under the international law of war in force at the time, which Germany had recognized in 1934 by signing the Geneva Prisoner of War Convention of July 27, 1929.

Although a harsh punitive decree had been issued in the Reich on September 5, 1939 against "deliberate exploitation of the exceptional circumstances caused by the course of the war," members of the Wehrmacht committed mass looting and even some rapes. For Jochen Böhler, this was "at the same time an expression of deep contempt for the Slav population and indifference to the suffering that was being caused."

It is also assumed that in September 1939 a total of between 4,000 and 5,000 Polish citizens of the German minority perished or were killed. Nazi propaganda increased the originally stated total number of German civilian casualties for the fall of 1939 tenfold to 58,000, including those murdered on "Bloody Sunday" in Bydgoszcz on September 3-4: Realistic estimates put the number of German victims at 300 to as many as 500. In retaliation, according to eyewitness accounts, Einsatzgruppe IV murdered 1,306 Poles - clergymen, Jews, women and youths - in Bromberg between September 7 and 12. Further murders and occupation crimes against tens of thousands of Poles in Bydgoszcz's surroundings were also justified by the Polish deed.

Some German army generals protested the "savagery," and courts-martial initiated some investigative proceedings for murders of Jews and Poles. But Hitler declared in September that he could not wage war by "Salvation Army methods." On October 4, 1939, together with Keitel and Roland Freisler, he had the proceedings terminated by the decree of pardon after the Polish campaign and amnestied the perpetrators.

Many war diaries of German soldiers report on activities of "gangs" and "guerrillas" who would have raided German Tross detachments. However, these were often scattered regular units of the Polish Army that had cut off rapidly advancing Wehrmacht units from their formations. Many murders of Polish civilians were passed off as part of partisan fighting.

Other war crimes, as defined by international law at the time, included the bombing of undefended Polish cities. According to British newspaper reports and information from the Polish Information Office in London, the German Air Force allegedly dropped bombs filled with poison gas on the Warsaw suburbs on September 3, 1939. Casualties were not mentioned.

See also: Crimes of the Wehrmacht

German occupation rule

→ Main article: German occupation of Poland 1939-1945

On October 4, 1939, in an additional protocol to the German-Soviet Border and Friendship Treaty, Germany and the Soviet Union defined the exact border line by which they divided Polish territory between them. The territories of eastern and southern Poland conquered up to this line became German General Government, and the former German eastern territories, which had been revoked in the Versailles Peace Treaty of 1919, and large parts of central Poland were annexed in the sense of the "arrondissement" sought by Hitler. The Soviet side agreed to this.

With the abolition of all existing Polish administrative authorities, district governments, political organizations and the establishment of new administrative districts, for which Hitler appointed administrative heads subordinate to the OKH, the occupation regime completely dissolved the nation-state of Poland. In doing so, it formally left the executive power in the Generalgouvernement to the army command, whose troops secured it. In fact, however, the Chief of the General Staff was almost exclusively concerned with operational command, while the administration was directed from Berlin, largely by simple decrees.

The German occupation policy aimed at "Germanization" as quickly as possible. About 200,000 Jews fled from the Germans to Soviet-occupied eastern Poland, increasing their numbers there from 1.2 to 1.4 million. By the end of 1939, about 90,000 Jews and Poles were expelled from the annexed territories to the Generalgouvernement, and a total of 900,000 by 1945. The remaining Jews were murdered in the Holocaust. In their place, a total of about 400,000 Reich Germans from the "Altreich" and 600,000 Volksdeutsche from all over Eastern Europe were settled in occupied Poland. These violent measures were in turn accompanied in many places by arbitrary mass shootings.

Government in Exile and Polish Resistance

→ Main article: Polish Government in Exile and Polish Underground State

In total, about 140,000 Polish military personnel fled to Romania, Hungary or Lithuania, where, however, many of them were interned under German pressure. In Romania, the Polish government was interned after their escape on September 17, 1939. As a result, President Ignacy Mościcki resigned. His office was taken over by Władysław Raczkiewicz, who lived in exile in France, and in October he constituted a Polish government-in-exile. The first seat of the government was Paris, later Angers. He had an exile army formed the following year and a national council formed in Paris in place of the dissolved Sejm. Many Poles who had fled to third countries subsequently managed to escape further to France and strengthen the new Polish forces. These troops, in association with Allied troops, took part in many important operations of World War II.

Despite the pleas of Roosevelt and Churchill to the contrary, Stalin declared the severance of relations with the Poles in exile on April 25, 1943. As the provisional government of Poland, the Soviet Union openly supported the Lublin Committee established in its sphere of power from about January 1945.

As a result of the brutal German policy of oppression, a broad resistance to the German occupying power was also formed in Poland itself. A veritable "underground state" was created, opposing the racist occupation policies of the Germans with a secretly produced press and a conspiratorial system of higher education. The military efforts of the Polish resistance culminated in 1944 under the aegis of the government-in-exile in an attempt to liberate the capital city of Warsaw by its own forces before the approaching Soviet troops. This ultimately unsuccessful Warsaw Uprising, which began on August 1, ended with an armistice agreed on October 1, 1944. This was followed by the deportation of the city's still-living civilian population, many to concentration camps, and the systematic destruction of Warsaw by the German Wehrmacht.

Polish Armed Forces at the Side of the Red Army

→ Main article: Polish Armed Forces in the Soviet Union

Part of the 1939 POWs who survived the Soviet gulags formed the army of General Władysław Anders in 1941 during the temporary cooperation with Josef Stalin, which came about at the insistence of Great Britain. Detouring through Persia and Palestine, this army resumed the fight against the Germans. It was deployed in North Africa and in Italy. More Poles were integrated into the 1st Polish Army of General Zygmunt Berling, raised by the Soviets, from 1943 and fought on the Eastern Front from 1944. This was later followed by the formation of a 2nd and 3rd Polish Army.

The Invasion of Poland and the Nuremberg Trial

With the invasion of Poland, the German Reich had not only broken the I Hague Convention for the Peaceful Settlement of Disputes and the III. Hague Convention on the Commencement of Hostilities, both of October 18, 1907, but also the Arbitration Treaty it had concluded with Poland at Locarno on October 16, 1925, and the Declaration of Nonaggression of January 26, 1934. The German annexation of the Free City of Danzig violated the Treaty of Versailles. Furthermore, the German war of aggression disregarded the Briand-Kellogg Pact of 1928.

At the Nuremberg trial of the principal war criminals from November 15, 1945 to October 1, 1946, the invasion of Poland was considered on charges of 1) conspiracy against world peace and 2) planning, unleashing and waging a war of aggression. The defendants Karl Dönitz (2), Wilhelm Frick (2), Walther Funk (2), Hermann Göring (1+2), Rudolf Heß (1+2), Alfred Jodl (1+2), Wilhelm Keitel (1+2), Konstantin von Neurath (1+2), Erich Raeder (1+2), Joachim von Ribbentrop (1+2), Alfred Rosenberg (1+2) and Arthur Seyß-Inquart (2) were convicted.

The conviction was based on the total breach of the ius ad bellum under Article 6a of the London Statute of August 8, 1945, according to which the planning and execution of a war of aggression constituted crimes against peace. In the face of the defense's objection that such a sentence contradicted the principle nullum crimen sine lege, the Nuremberg Main War Crimes Tribunal stated:

"To assert that it is unjust to punish those who, in violation of treaties and assurances, have attacked their neighboring States without warning, is clearly incorrect, for in such circumstances, after all, the aggressor must know that he is doing wrong, and far from it not being unjust to punish him, it would rather be unjust to allow his outrages to go unpunished. In view of the position which the defendants occupied in the Government of Germany, they, or at least some of them, must have had knowledge of the treaties signed by Germany in which war was declared unlawful as a means of settling international disputes; they must have known that they were acting in defiance of all international law when they carried out with full forethought their intentions directed to invasion and attack."

Back row from left: Karl Dönitz, Erich Raeder, Baldur von Schirach, Fritz Sauckel, Alfred Jodl, Franz von Papen, Arthur Seyß-Inquart, Albert Speer, Konstantin von Neurath, Hans Fritzsche. Front row from left: Hermann Göring, Rudolf Heß, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Wilhelm Keitel, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Alfred Rosenberg, Hans Frank, Wilhelm Frick, Julius Streicher, Walther Funk and Hjalmar Schacht.

Polish prisoners of war in a transit camp (September 1939)

Shootings of Poles by a German Einsatzkommando (October 21, 1939)

Shot prisoners of war in Ciepielów (September 9, 1939)

Partition of Poland in 1939 by the aggressors Germany and the USSR

Bodies of Polish soldiers in a ditch (September 1939)

_bei_Aufräumungsarbeiten.jpg)

Polish residents, presumably Jews, cleaning up bombed Warsaw (September/October 1939)

On the reception after 1945

In January 1946, the new communist rulers adopted a decree entitled "On Responsibility for the September Defeat and the Fascicization of State Life." This document marked out the main direction of the communist "politics of memory" for about ten years. "The reason for the defeat in September" had been "the criminal Sanacja regime and the unlawful actions of its leaders at the time." These had "promoted the spread of fascism by weakening the material and spiritual defenses of the nation" and were therefore complicit in the war.

Martin Sabrow wrote in 2009 that there were "taboos and blind spots" in the war memory of West Germany and East Germany:

"In the West, the mass murders behind the front in the East, covered by the Wehrmacht and carried out with its participation, and the extermination of intellectual elites in Poland and Russia remained virtually hidden for decades, [...] also the communist resistance to Hitler's rule and the participation of German society in the Nazi break with civilization."

See also

- Chronology of the Second World War, as of January 1939

- Unternehmen Tannenberg (deployment of five Einsatzkommandos, EK, behind the advancing army; using the Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen)

Movies

- Alexander Hogh, Jean-Christoph Caron (directors): Poland 39. How German soldiers became murderers. TV documentary, Germany 2019, 52 min., ZDF

Questions and Answers

Q: What countries invaded Poland in 1939?

A: Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union invaded Poland in 1939.

Q: When did the invasion of Poland take place?

A: The invasion of Poland took place from 1 September to 6 October 1939.

Q: What was the result of the invasion?

A: In the end, Poland lost and Germany and the Soviet Union divided the country according to a treaty signed years before the war.

Q: How effective was blitzkrieg against Polish forces?

A: Blitzkrieg was very effective against the ineffective and demobilized Polish Army, whose tanks and airplanes were nearly out and mostly old. They were easily destroyed by Blitzkrieg.

Q: How did Britain and France respond to Germany's invasion of Poland?

A: Britain and France declared war on Germany on 3 September but they did little to affect the September Campaign.

Q: What happened during Battle of Mokra on 2nd September?

A: During Battle of Mokra on 2nd September, Poles repulsed an attack by a German Panzer division forcing their retreat.

Q: What happened to most of Polish Navy after German Invasion?

A: Most of Polish Navy escaped to Britain after German Invasion.

Search within the encyclopedia