Indian reservation

In German, Indian reservations (also: Indianer-Reservationen) are concretely defined areas with separate legal status, which were assigned to indigenous ethnic groups of America ("Indians") by various states. Their establishment occurred as a result of the colonization of the Americas, predominantly in the 19th century. In some cases (particularly in the remaining wilderness areas of Canada and Amazonia), such reservations are located on former tribal territory, but in most cases they constitute only a small to very small portion of that territory. The geographic location and extent was determined without any co-determination of the affected people, in contrast to autonomous regions of indigenous peoples (such as the Indian land areas in Canada's Yukon Territory or the autonomous regions of Nicaragua).

Indian reservations exist under the following designations in some states of North, Central, and South America:

- Canada: Indian reserve or French réserves indiennes

- USA, Belize: English Indian reservation

- Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Guyana: Spanish Territorios Indígenas

- Dominica: English Carib Territory

- Panama: Spanish Comarcas indígenas

- Venezuela: Spanish Tierras con títulos colectivos

- Colombia: Spanish Resguardos indígenas and Reservas indígenas

- Peru: Spanish Reservas comunales and Spanish Reservas territorial para pueblos indígenas en aislamiento

- Brazil: Portuguese Terras indígenas

- Bolivia: Spanish Tierra Comunitarias de Origen or Territorios indígenas originario campesino

- Argentina: Spanish Posesión y propiedad comunitarias de las tierras de argentina

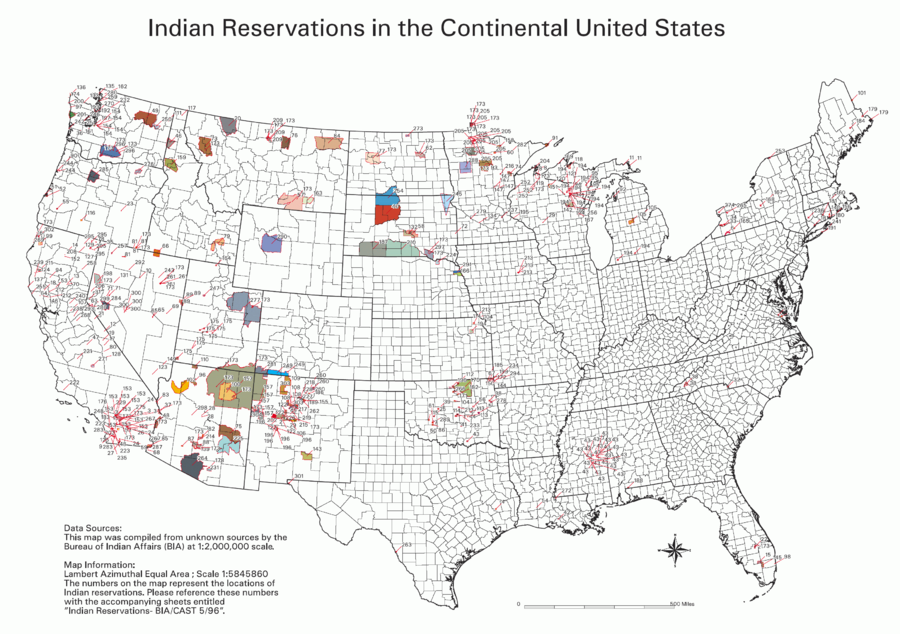

Most of the reservations in North America, and the largest in terms of area, are located in the western part of the USA - concentrated in the mountain states of Arizona, Utah and Montana, as well as in South Dakota. In Canada, First Nations reserves are scattered across more than 3000 small and micro units.

The largest reserves in the Americas are in Brazil. In Colombia and Brazil, the larger reserves are located in the border areas with neighbouring countries and in the drainage area of the Amazon.

Indian reservations in Canada and the United States.

History

Before colonization, well over a thousand Native American ethnic groups populated the North American continent. As a result of systematic land grabbing and planned reclamation by European settlers, they came under increasing pressure and lost much of their land.

Authors describe the reservations in their early days as prison camps, which the Indians were only allowed to leave with permission. The restricted reservation life made it impossible for the Indians to be self-sufficient. They were dependent on food rations, which were used as leverage by government officials. If individual Indians showed resistance, their food rations were withheld, leaving the Indians with no choice but to comply or seek sustenance elsewhere outside the reservation.

Various images of reservations existed. In addition to prison camps, in the early days people spoke of reservations as "schools for civilization and education". Once Indians were sufficiently "civilized," they would be allowed to leave the reservations. Others saw them as the key to the survival of Indian culture.

Most reservations were created by treaty. The Indians had, in a sense, reserved land for themselves; the government had no authority to reserve land for the Indians, as it was mostly acknowledged to belong to the Indians. Some reservations had been created by land swaps during the relocation period. In the U.S., after the government moved to stop making treaties with the Indians in 1871, the Indians had been stripped of any say in the matter. Now the US government determined the new creation, reduction or enlargement of reservations ("enactment reservations"). These are lands provided by the government, which it can dispose of again at any time. Land purchases enlarged reservations; rarely were entire reservations established by purchase. The same applies to donations, which were essentially made by church institutions.

In Canada, numerous tribes formally transferred their former lands to the Kingdom of England by treaty (especially between 1867 and 1923). Instead, they received much smaller, tradable plots of land. Also written into the treaty was the amount of food rations the Indians were to receive as compensation in perpetuity, and financial compensation, which was about twelve dollars per person. Chiefs would receive an additional $25 or so per year. In addition, the Canadian government undertook to provide education and health care for the reservation Indians. Fishing and hunting rights continued to be granted to them in some cases. There were many different treaties with widely varying terms and some groups today argue that the Native side did not have the legitimacy to enter into these treaties.

Most U.S. reservations are very small and about 93% of them are located in states in the western United States. Only just three percent are located east of the Mississippi River.

Contemporary life

Mineral Resources

Often, the Indians were allocated reservations in semi-arid to arid areas, which were initially not very desirable for the white settlers. Later, however, it was precisely in these areas that large deposits of mineral resources were discovered. For example, about 55% of all uranium deposits in the USA are in the soil of the Indians. The health consequences of uranium mining are devastating for the Indians. Their land is also rich in oil (about 5% of all US reserves) and coal (about one-third of all US reserves). The Indians have little recourse against mining. The right to mine is granted in the US by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The revenues from this are also marginal for the Indians.

In Canada, most revenues from such transactions are administered by the authorities in Ottawa. The Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (INAC) is responsible here.

Work situation

Uranium mining and its consequences are only one problem of many that the reservation Indians have to deal with. In general, poverty is very high, living conditions are compared to the Third World. Since 1980, the unemployment rate has hovered between 40% and 80%, depending on the reservation. According to BIA statistics, the unemployment rate on reservations in 1985 was 39%. On U.S. reservations, more than 40% of families were living below the poverty line in 2002. Some reservations, however, have much higher unemployment rates, in some cases over 80%. Yet the public sector is by far the largest employer. The BIA, Indian Health Service (IHS), and other Indian agencies alone employed nearly 60 percent of the reservation workforce in 1980. In contrast, just five percent were employed in the service sector, 16% in the secondary sector, and ten percent in the primary sector. About one-third of all reservation Indians have jobs outside the reservation boundaries. Primarily due to the poor employment situation, a total of only 30 % of all Indians in the USA still live on the reservations.

Industry

Industrial enterprises are hardly ever found on reservations. This is an expression of the collective consciousness that still determines the everyday life of the Indians. There is very little interest in stocking up on cash reserves and material goods through high incomes, as is the case in the European conception of life. Regular, continuous work is not seen as the standard by many members of Indian communities. Rather, they engage in sporadic work that again satisfies their basic needs for a while. They are less likely to make financial provision than the rest of the American population. In addition, there is a less pronounced sense of competition. All of these factors inhibit the development of industry on reservations. Other negative conditions militate against the Indian reservation as an industrial location. For example, the isolated location, the low-income and thus low-purchasing power of the inhabitants, the lack of infrastructure such as repair and service outlets, bank branches, means of communication and energy sources, railway connections, public transport, and the quality and density of the road network severely restrict industry. Add to this a climate of political instability and opaque jurisdictional disputes. Questions about with whom potential investors must negotiate or what competencies the respective negotiating partner has are difficult to clarify. A lack of capital is also an important obstacle. Hardly any industrial enterprises can be financed by the Indians. In addition, the reservations and their inhabitants are usually not considered creditworthy.

In addition, there are also factors that promote the economy, such as the large pool of labour. The high unemployment rate means cheap labour for the entrepreneurs. The environmental protection regulations in the reservations are very low, their control practically non-existent. Targeted tax breaks and government economic incentives are designed to attract investors. Compared to a foreign industrial location with cheap wages, there are no customs duties and currency risks in reservations.

Canadian legislation does not allow land within reserves to be sold to non-aboriginal people. Therefore, mortgages and loans on them are not tradable. Therefore, there is little investment activity.

For some time, many U.S. reservations have been improving their economic bases through Indian casinos.

School system

In addition to the work situation, the school system is also problematic; for a long time, Indian children were often only offered boarding schools (compare Residential School). These usually did not aim at education, but rather at identity deprivation. The schools were often used by the state as a welcome tool to implement its assimilation policy. Subjects such as history, civics, geography and English served as suitable means to pass on the values of the dominant majority society and to convince the Indians of their cultural inferiority.

Attending boarding schools often led to negative psychological and social consequences for Indian children, who were forcibly removed from their familiar socio-cultural milieu at a very early age and were often unable to see their families for years.

After 1928, there were fewer and fewer such off-reservation boarding schools; instead, the BIA built schools on the reservations themselves. However, according to a 1980 survey, 16% of all Indians attended school for less than eight years; the national average was 10%. If only Indians living on reservations are considered, the figure is 26%. Compared to the national average, this is very high, but compared to the 1970 survey, when the percentage was 50% for reservation Indians, it appears relatively low.

Until 1967, it was the practice in Canada for children to remain in boarding school all year round in partially nomadic groups. It was not until 1970 that this practice was revised. Around 1990, cases of sexual abuse at such schools became public. In 2008, the Prime Minister apologized to the aboriginal people for these schools and the conditions that prevailed at them.

Property rights (USA)

About 80 % of the reservation land is owned by the tribal government, despite the parcelling policy around 1900. The respective tribe grants usage rights to its members. This handling represents the traditional collective system of the Indians. Depending on the reservation, however, there is quite high individual ownership, for example, on the Pine Ridge Reservation of the Lakota or the Crow Reservation, where individual ownership ranges from 60 to 85%. On the Osage Reservation, it is as high as nearly one hundred percent. Most of the land is held in trust by the BIA. Because of the special status of Indians, individual landowners do not pay property taxes.

Since the plots are too small for self-sufficiency and there is often little interest in farming anyway, leasing means the only income possibility. In 1984, 13.6% of the reserve land was leased. Today, much of the reservation land is in the hands of whites. On the Crow Reservation, for example, a quarter of the land is owned by whites and 65% is leased to agribusinesses.

Property rights (Canada)

Due to the many different histories of the origins of the reserves in Canada (treaties, decrees), it is hardly possible to make generally valid statements. Although a law of 1876 allowed the aborigines to manage the income from the use of the reserves, until 1959 only about 20 % of the 600 reserves in Canada were at least partially self-managed.

System of government (USA)

Indian reservations are predominantly self-governing, although financial grants, without which Indians cannot live, account for about 70% of all tribal revenues. Most ethnic groups have a constitution based on that of the United States. However, the jurisdiction of the tribal government is severely limited. Depending on their status and on the type of treaties they have signed with the US government in the past, their powers vary.

Many reservations are still under the administration or supervision of the BIA, which often acts against the interests of the Indians, although its management has been in Indian hands since 1965. Traditionally minded Indians are hardly interested in a position at the BIA and so the central positions at the BIA are often occupied by progressive "half-breeds" who sometimes show little understanding for the Indian collective.

List of US reservations

→ Main article: List of Indian reservations in the United States

According to the U.S. Department of the Interior's National Park Service, there are currently 304 registered Indian reservations in the United States. The 2001 census in Canada lists 600 reserves, 976,305 Canadian citizens with aboriginal status, of which 286,080 live on reserves.

| 1 – 100 | 101 – 200 | 201 – 300 | 301 – 304 |

| 1. absentee Shawnee | 101st Houlton Maliseets | 201. quinault | 301st Ysleta del Sur |

| 2. Acoma | 102nd Hualapai | 202. Ramah | 302. Yurok |

| 3. agua caliente | 103. Inaja | 203. Ramona | 303rd Zia |

| 4. alabama coushatta | 104th Iowa | 204. red cliff | 304. Zuni |

| 5. Alabama-Quassarte Creeks | 105th Isabella | 205. red lake | |

| 6. allegany | 106. isleta | 206th Reno-Sparks | |

| 7. apache | 107. Jackson | 207th Rincon | |

| 8. bad river | 108th Jemez | 208. Roaring Creek | |

| 9. Barona Ranch | 109th Jicarilla | 209. rocky boys | |

| 10th Battle Mountain | 110. Kaibab | 210. Rosebud | |

| 11th Bay Mills | 111. calisel | 211 Round Valley | |

| 12. Benton Paiute | 112th Kaw | 212. rumsey | |

| 13. berry creek | 113th Kialegee Creek | 213. sac and fox | |

| 14. big bend | 114. kickapoo | 214 Salt River | |

| 15. big cypress | 115. kiowa | 215. sandia | |

| 16. big lagoon | 116th Klamath | 216. sandy lake | |

| 17. big pine | 117th Kootenai | 217th Santa Ana | |

| 18. big valley | 118. L'Anse | 218th Santa Clara | |

| 19. bishop | 119. Lac Courte Oreilles | 219th Santa Domingo | |

| 20. blackfeet | 120. Lac du Flambeau | 220. santa rosa | |

| 21. Bridgeport | 121. Lac Vieux Desert | 221 Santa Rosa (north) | |

| 22nd Brighton | 122. laguna | 222. santa ynez | |

| 23rd Burns Paiute Colony | 123. Las Vegas | 223rd Santa Ysabel | |

| 24. cabezon | 124. laytonville | 224. santee | |

| 25th Caddo | 125. La Jolla | 225. San Carlos | |

| 26th Cahuilla | 126. la posta | 226 San Felipe | |

| 27th Campo | 127. Likely | 227 San Ildefonso | |

| 28 Camp Verde | 128. lone pine | 228. san Juan | |

| 29. canoncito | 129th Lookout | 229. san manual | |

| 30. Capitan Grande | 130. Los Coyotes | 230. San Pasqual | |

| 31st Carson | 131st Lovelock Colony | 231st San Xavier | |

| 32nd Catawba | 132. lower brulé | 232nd Sauk-Suiattle | |

| 33. cattaraugus | 133rd Lower Elwah | 233rd Seminole | |

| 34. cayuga | 134. Lower Sioux | 234. seneca cayuga | |

| 35. cedarville | 135. lummi | 235. sequan | |

| 36. chehalis | 136. makah | 236. shagticoke | |

| 37th Chemehuevi | 137th Manchester | 237. Shakopee | |

| 38th Cherokee | 138th Manzanita | 238. sheep ranch | |

| 39. cheyenne-arapahoe | 139. maricopa | 239. sherwood valley | |

| 40th Cheyenne River | 140. mashantucket pequot | 240. shingle spring | |

| 41st Chickasaw | 141 Mattaponi | 241st Shinnecock | |

| 42nd Chitimacha | 142. menominee | 242nd Shoalwater | |

| 43rd Choctaw | 143rd Mescalero | 243. shoshone | |

| 44th Citizen Band of Potawatomi | 144. Miami | 244. flint | |

| 45th Cochiti | 145th Miccosukee | 245. sisseton | |

| 46th Coeur d'Alene | 146th Middletown | 246. skokomish | |

| 47. cold springs | 147th Mille Lacs | 247th Skull Valley | |

| 48. Colorado River | 148. mission | 248. Soboba | |

| 49th Colville | 149. moapa | 249. Southern Ute | |

| 50th Comanche | 150. modoc | 250. spokane | |

| 51st Coos, Lower Umpqua & Siuslaw | 151st Mole Lake | 251st Squaxon Island | |

| 52. coquille | 152nd Montgomery Creek | 252nd St. Croix | |

| 53rd Cortina | 153rd Morongo | 253rd St. Regis | |

| 54. coushatta | 154. muckleshoot | 254. standing rock | |

| 55th Cow Creek | 155. Nambe | 255. Stewart's Point | |

| 56. creek | 156th Narragansett | 256th Stockbridge-Munsee | |

| 57th Crow | 157th Navajo | 257th Summit Lake | |

| 58. Crow Creek | 158. nice lake | 258. Susanville | |

| 59. cuyapaipe | 159 Nez Perce | 259. swinomish | |

| 60th Deer Creek | 160. nipmoc-hassanamisco | 260. taos | |

| 61st Delaware | 161st Nisqually | 261st Te-Moak | |

| 62. devils lake | 162nd Nooksack | 262nd Tesuque | |

| 63rd Dresslerville Colony | 163. northern cheyenne | 263rd Texas Kickapoo | |

| 64. dry creek | 164. northwestern shoshone | 264. tohono o'odham | |

| 65. Duckwater | 165. oil Springs | 265. tonawanda | |

| 66. Duck Valley | 166 Omaha Indian Reservation | 266. tonikawa | |

| 67th Eastern Shawnee | 167. oneida | 267 Torres Martinez | |

| 68th East Cocopah | 168. onondaga | 268. toulumne | |

| 69. ely colony | 169. ontonagon | 269. trinidad | |

| 70th Enterprise | 170. osage | 270. tulalip | |

| 71. fallon | 171st Otoe-Missouri | 271st Tule River | |

| 72. flandreau | 172. ottawa | 272. tunica biloxi | |

| 73rd Flathead | 173. out | 273rd Turtle Mountains | |

| 74. fond du Lac | 174. ozette | 274. Tuscarora | |

| 75th Fort Apache | 175. paiute | 275. Twentynine Palms | |

| 76th Fort Belknap | 176. pala | 276. umatilla | |

| 77th Fort Berthold | 177. pamunkey | 277. Uintah and Ouray | |

| 78th Fort Bidwell | 178. Pascua Yaqui | 278. United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee | |

| 79th Fort Hall | 179th Passamaquoddy | 279. upper Sioux | |

| 80th Fort Independence | 180. paucatauk pequot | 280. upper skagit | |

| 81st Fort McDermitt | 181st Paugusett | 281st Ute Mountain | |

| 82nd Fort McDowell | 182. pawnee | 282nd Vermilion Lake | |

| 83rd Fort Mohave | 183. pechanga | 283rd Viejas | |

| 84th Fort Peck | 184. Penobscot | 284th Walker River | |

| 85th Fort Yuma | 185. Peoria | 285 Warm Springs | |

| 86th Ft. Sill Apache | 186. picuris | 286. Washoe | |

| 87th Gila Bend | 187 Pine Ridge Indian Reservation | 287th West Cocopah | |

| 88th Gila River | 188. Poarch Creek | 288. white earth | |

| 89th Goshute | 189. pojoaque | 289. Wichita | |

| 90th Grande Ronde | 190. Ponca | 290. wind river | |

| 91. Grand Portage | 191st Poosepatuck | 291st Winnebago | |

| 92nd Grand Traverse | 192. port gamble | 292nd Winnemucca | |

| 93. greater leech lake | 193. Port Madison | 293rd Woodford Indian Community | |

| 94. grindstone | 194. Potawatomi | 294th Wyandotte | |

| 95. Hannahville | 195. Prairie Isle | 295. XL Ranch | |

| 96th Havasupai | 196. puertocito | 296. yakama | |

| 97. Hoh | 197. Puyallup | 297th Yankton | |

| 98th Hollywood | 198. pyramid lake | 298. Yavapai | |

| 99th Hoopa Valley | 199. quapaw | 299th Yerington | |

| 100. Hopi | 200. quileutes | 300. yomba |

Movies

- In 1969 DEFA made the feature film Tödlicher Irrtum (Deadly Mistake), which deals with the life of the Indians on a reservation. The white Americans' greed for oil, their unscrupulousness in obtaining it, and the coexistence of the two fundamentally different groups of people are portrayed in an exciting way that is as close to history as possible.

- In 1973/74 DEFA made the feature films Apaches and Ulzana, which basically deal with the same subject, but specifically focus on the coexistence of the Apaches with the European settlers.

American films that deal with life on reservations include:

- 1992: Half-Blood (original title: Thunderheart)

- 1994: Dance with a Murderer (Original title: Dance Me Outside)

- 1998: Smoke Signals

- 2002: Skins

- 2003: Dreamkeeper

- 2008: Rez Bomb

- 2017: Wind River

Reservations in the USA (without Alaska)

See also

- United States Indian Policy

- American Indians

- History of the First Nations

- List of Indian tribes recognized in Canada

Questions and Answers

Q: What is an Indian reservation?

A: An Indian reservation is a place in the United States where Native Americans manage their own land under the US Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Q: Who manages Indian reservations?

A: Native Americans manage Indian reservations under the US Bureau of Indian Affairs, and they are not managed by state governments.

Q: How many Indian reservations are there currently?

A: There are currently 326 Indian reservations in the United States.

Q: Do all Native American tribes have their own reservations?

A: No, some Native American tribes do not have their own reservations.

Q: Can one reservation be shared by multiple tribes?

A: Yes, in some cases, a reservation may be shared by two or more tribes.

Q: Where do many Native Americans and Alaska Natives live now?

A: Many Native Americans and Alaska Natives no longer live on Indian reservations and have moved to larger cities like Phoenix and Las Vegas.

Q: What did the 2000 United States census show about Native Americans and Alaska Natives?

A: The 2000 United States census showed a larger number of Native Americans and Alaska Natives no longer lived on Indian reservations.

Search within the encyclopedia