Icon

![]()

This article is about the sacred image. See also: icon (disambiguation) or icons (disambiguation).

Icons (from ancient Greek εἰκών eikṓn, later īkṓn, "[the] image" or also "likeness"; as opposed to εἴδωλον eídolon, later ídolon, "mirage, dream image," and εἴδος eídos, later ídos, "archetype, figure, type") are cult and holy images venerated predominantly in the Eastern churches, especially the Orthodox churches of the Byzantine rite by Orthodox Christians, but they were also produced by and for nonOrthodox Christians.

Icon painting developed out of the resources and painting techniques of late antique figurative painting, in which portraits of the dead, emperors, and gods served as models. It originated from the interest of a central power with a sacral understanding in the realm of the imperial court, whose image policy prevailed throughout the Byzantine Empire. Only with time did it find its own formal language, which for centuries was fundamental for the representation of portraits of saints in European and other Christian societies. This own style of icon painting, which included its own aesthetic norm and distinguished it from wall frescoes, can be established at the earliest in the course of the 6th century. The heritage of icon painting is at the beginning of European panel painting. It was also the only one in the period between the 5th and 15th centuries for over 1000 years. After the fall of Byzantium, it was continued by other cultures in Europe and the Middle East. Icon paintings are an independent form of painting through perspective, coloration and representation. Basic stylistic design feature is perspective summary of non-euclidean geometries and simultaneous use of curved surfaces with inverse perspective (here objects that are far from the viewer are shown larger) and bird's-eye view as well as frontal illustration. The inverse perspective, also called reverse perspective, is also found in almost all evageliars and book paintings in Central Europe. This always in direct reference to Christ or saints. The perspective representation of icon painting thus remains unaffected by dogmas of Renaissance perspective (central perspective). The inverted perspective as a design feature is responsible for the typical "eccentric" representation in icons in many eyes. While the reverse perspective can be found already in the high Middle Ages in the book painting of the West it becomes popular in the Russian and Byzantine icon painting from the 14th to the 16th century. Art historically, among other characteristics, it distinguishes paintings of "icon art" from other styles. In the tradition of icon veneration, Eastern and Western churches differentiated themselves since the 8th century through the Libri Carolini in Charlemagne's Frankish Empire, which excluded veneration through the age of the Reformation. In this period, the Calvinist direction banned images. As a result of the Reformation iconoclasm, the image lost its liturgical function in the Church. In the Eastern Churches, except in times of the iconoclastic controversy, icon worship remained part of philosophical and theological tradition. Western panel painting, which started from Italy in the 13th century, directly follows the recent development of Byzantine icon painting. It differs, however, mainly in the design of the picture supports, in which the standard size of the icon is abandoned. From this, through a rapid change in design, the altarpiece developed, which in the course of time had less and less in common with the icon. The role of the icon in the High Middle Ages in Rome remains unbroken: in them the social structure of the city was reflected. They were a means of religious, political and social articulation. The import of Byzantine icons remained fundamental. Wherever they appeared, a cult was established around those that appeared to be of great age, which helped the place of their installation to gain power and wealth. In Venice, for example, it was the Byzantine icon Nicopeia who, as the patron saint of the state, embodied the sovereign in supplications and ceremonies.

The importance of miraculous acheiropoieta, which originated from the Jerusalem rites of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, was transformed into central cult objects of the empire and the capital through icon processions held in Constantinople several times a week between the patronages of the Virgin Mary. From this practice, the countries of Slavic Orthodoxy, where especially in Moscow and Russia the rite of processional icons was significant, subsequently as post-Byzantine centers, adopted icon painting. The images, mostly painted on wood, are consecrated by the Church, have a very great importance for the theology and spirituality of the Eastern Churches, and are also widespread in the private sphere as devotional images. The purpose of icons is to inspire awe and create an existential connection between the viewer and the sitter, and indirectly between the viewer and God. Icon painting was considered a liturgical act and was precisely defined in terms of composition and coloring as well as materials in the Painter's Book of Mount Athos. Icons are placed in Orthodox churches according to a certain scheme at the iconostasis, in which the large-sized deesisicons form the main row. They are an essential part of Byzantine art and influenced the development of medieval European panel painting, especially the proto-Renaissance in the Maniera Greca.

The Oriental Orthodox churches, for example the Coptic Church and the Armenian Apostolic Church, also venerate icons in their cultus, but not the Assyrian Church. In Coptic icons, influences of ancient Egyptian art can be found.

Andrei Rublev's icon of the Trinity is a widely copied prototype of an icon representation. The artistic treatment of the doctrine of the Trinity exemplifies theological dogmatics and formular use of an inverted perspective in icon art, c. 1411

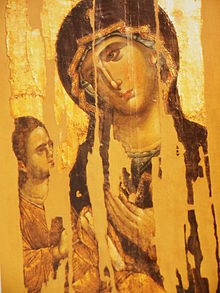

Mother of God of Vladimir. The Mother of God Eleusa icon is a work of imperial workshops from the time of the Comnenes, Constantinople around 1100.

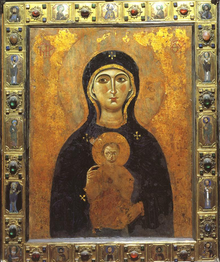

The state icon of Venice, the Nicopeia, arrived in Venice as war booty of the Fourth Crusade in 1204. Constantinople, 11th century. Today in the Cappella della Madonna Nicopeia in St. Mark's Basilica.

Word Origin

In the meaning "cult image" the word icon was borrowed as an exoticism in the 19th century from Russian икона ikóna. This word goes back to Church Slavonic икона ikona, which is derived from Middle Greek εἰκόνα ikóna. Underlying it is ancient Greek εἰκών eikṓn ([ejˈkɔːn]) "likeness, pictorial representation." Until the 5th century, the term eikon had a general meaning, from the image of the dead to the portrait of a saint. From the 6th century the term graphis became established for secular portraits and eikon exclusively for religious paintings.

This is also the origin of the name of the Shroud of Veronica, whose name "Veronica" as Vera Icona comes from the words vera (fem., Latin for "genuine, true, authentic") and eikon (see above).

At the same time, images are the basic form of masks, which are transformed into icons through the image of Christ on a cloth. According to Belting, icons are living masks that replace the mask theater of antiquity in the church space from liturgical practice.

Design Features

Form and representation

Icons are mostly icons of Christ, Mary (especially so-called Theotokos representations), apostles or saints. According to Orthodox belief, many protagonists of the Old Testament are also saints and are therefore depicted on icons as well as the saints of later times. Certain scenes from the Bible, the lives of the saints or typological groupings find their reproduction as Hetoimasia, Deesis, Transfiguration or Trinity icons. An icon in the center of which a saint is depicted, surrounded by a wreath of smaller images with pictures from his vita, is called a vitenicon. Icons have common features in their depiction that deviate from Western European and post-Gothic ideas of art, and which are often theologically based.

- The motifs and types are fixed in the medieval Byzantine iconography (image canon) and already written icons were used as painting templates. Already Andrei Rublyov, however, changed icon schemes, which are used today even as copyable templates (for example, the depiction of the Old Testament Trinity without the actually obligatory Abram and Sarai).

- New motifs are made according to the iconography of existing icons or according to the specifications of the canon (gestures, facial expressions, coloring, etc.). In the 20th century, the number of saints in the Western Church has greatly increased, and the desire to decorate private homes or churches with an icon is growing. An icon in the cathedral of Hildesheim, the so-called "Hildesheim Cathedral Icon", which unites the patrons of the cathedral and the church itself in a new creation, is worth mentioning. Examples from the Eastern Church are the icons of various "new martyrs," i.e., victims of communist persecution of Christians, which have become widespread since 1990.

- The figures on individual icons, which, however, make up only a small part of all icons, are often depicted frontally and axially in order to create an immediate relationship between the image and the viewer.

- The depiction of people in old painting styles is strictly two-dimensional, the special perspective aims at the depiction itself. This emphasizes that the icon is an image of reality, not reality itself. Since the Baroque period, however, icons in a naturalistic manner and in completely Baroque church furnishings have also existed as icons to be legally venerated by the church. Thus, the newly built Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow represents a pure church in the Nazarene style.

- The background on medieval icons is usually gold-colored (more rarely silver), created mostly by gold leaf, impact metals or even ocher color. The golden background symbolizes the sky or the "divine light" as the highest quality of light. Serbian icons often show a blue background, Greek ones different color backgrounds. However, Russia in the Middle Ages also knew red-grounded icons (Christ in the throne with chosen saints and St. John Klimakos with marginal saints; both Novgorod second half of 13th century).

- The shapes are often structured and clear, with a flat background, without physicality, as this would be earthly (light and shadow).

- The colors, the relative size of the figures, their positions and the perspective of the background were not realistic in the Middle Ages, but had symbolic meaning. The perspective of the background and of objects in the foreground (e.g. tables, chairs, chalices) is often deliberately constructed "wrong", so that the vanishing point is in front of the image (reversed perspective). The surroundings often recede behind the venerable person.

- All persons are identified by inscriptions (abbreviations) in the respective language (e.g. Greek, Russian, Old Slavonic) in order to ensure that the reference to a real person is maintained and that the veneration of the icon does not take on a life of its own. A Christian icon becomes an icon only through the inscription; icons without inscriptions are not images worthy of veneration and are not consecrated. Even otherwise, scrolls or books with texts are often found in the hands of the saints, which, as in Romanesque and Gothic art, are remotely comparable to the speech bubbles of a comic strip. A pantocrator icon is often given a gospel book in its hand, which reproduces a New Testament passage associated with the intention of the icon. Often, however, the evangeliary is closed. Icons of saints who left written or oral teachings are often depicted with a book whose open pages contain a central statement of their teaching.

- The individual, creative expression of the painter is irrelevant from the church's point of view. Icon painting is seen as a spiritual craft, not as art, which is why the word "hagiographia", i.e. saint writing, is closer to the production of an icon. In icon writing, the painter is seen as an "instrument of God." Often icons were made by monks, anonymous scribes, or in manufactories or painting schools by several scribes. Classically, icons are not signed.

- The varnish of an icon consists of oil, more rarely of wax or dammar resin solution, in more recent times also of synthetic resins.

Icons today are usually panel paintings on primed wood in egg tempera without frames. Increasingly, painting is done on primed canvas, which is mounted on wood after completion. In ancient times, on the other hand, painting was mostly done in encaustic. There are also mosaics, frescoes, carved icons (ivory, wood) as bas-reliefs or enamel castings. Full-size statues and statuettes, on the other hand, were rare in the ancient church and subsequently in the Eastern Church, as they were all too reminiscent of the idols of paganism.

Perspectives in icons

Byzantine painting was particularly interested in the disinterest in realistic representation of objects and the non-use of the principle of central perspective. Central perspective had been known since 480 B.C. and was first integrated into Roman art for backdrops in theaters, and later in the illusionistic fresco painting of living walls through Hellenistic mediation. While late antique art was fundamentally perspective, it disappeared during the 4th century and did not reappear until the end of the Middle Ages. The lack of three-dimensionality in icons is explained by Russian authors due to an idea of a painting space that was not intended to be three-dimensional. Icons also do not simply have an inverted perspective as Oskar Wulff brought to art historical analysis in 1907, but they possess multiple perspectives. A fundamental work on inverted perspective was done by Pavel Alexandrovich Florensky (1920). His interpretation was further developed and reformulated by Clemena Anotonova. Anotonova introduced the notion of simultaneous planes for perspective in icons. This idea is based on the contextualization of culture in the Middle Ages, i.e. in the spiritual presence in both the production and use of icons. In Orthodox culture, icons are symbolic reference of the presence of the divine, transformed in the representation of saints and connection to relics. From the historical associations of what is represented in the image, the observer confirms this presence. Icons thus represented timeless and spaceless perspectives of the presence of God. In the use of the inverted perspective, there is a representation of the view of all planes that are actually simultaneously inaccessible to the human eye. This is the medieval representation of the vision of the divine, in which all planes and perspectives are represented at once. They are thereby not perspectives of the human, but of a divine figure as this would see the scene. A human observer is enabled to transcend in time and space from the point of view of different planes that emanate in perspective from a divine vantage point and all-encompassing knowledge.

Historical representations

·

Icon of Notre-Dame de Grâce, Italo-Byzantine, c. 1340. Patroness of the Archbishopric of Cambrai. A copy of this can be found in Lourdes

·

Eleusa type of the Mother of God, Zvonik (Croatia)

·

Byzantine double icon (Constantinople, beginning of the 14th century): obverse with Our Lady saving souls

·

Icon of the Hodegetria from the late 16th century in the Cathedral of Piana degli Albanesi

Contemporary representations and techniques

· ![]()

Presentation of the Child Jesus in the Temple

· ![]()

The Twelve Apostles surmounted by Christ Pantocrator in a medallion

· ![]()

Scheme of representation of female head

· ![]()

Scheme of light on face, hands and feet of virgin and child

Theology of icons

The icon serves the visualization (representation) of Christian truths. In the course of the Byzantine iconoclastic controversy, the church father John of Damascus and the church teacher Theodor Studites provided the theological justification for the representation of icons through the idea of the incarnation: the incarnation of God in Jesus Christ was the first thing that made pictorial representation possible; God the Father was still not allowed to be represented. The biblical prohibition of images (Exodus 20, 4 f.), justified by the invisibility of God in pre-Christian times, was not violated, because God himself had broken through it in the visible Christ. The mandylion, the "image of Christ not made by human hands", which had miraculously come into being, as it were, by the will of Christ, could be regarded as the "founding icon". Accordingly, the veneration of icons in the form of metanies, kisses, candles and incense was not directed at the image, but at the truth present "behind" the image. Besides images of Christ, images of saints could also be venerated, because in the saints the Holy Spirit was active, who was God himself and therefore rightly venerated in this way. Here Plato's doctrine of ideas, which is illustrated in his allegory of the cave, is at work. In this sense the image controversy was finally decided - under certain conditions - in favor of the images.

Numerous typologies of icons have developed. Most icons are painted according to certain patterns and models. Nevertheless, the icon painters are free in the design of the details.

Icons are an essential expression of Byzantine art. This art was further cultivated in Greece, Bulgaria and especially in Russia. Important schools of icon painting were located in Vladimir, Novgorod, Tver and Moscow.

While in the 18th and 19th centuries Western influences changed icon painting or even distorted it from a non-Orthodox point of view, the 20th century saw a return to the Byzantine foundations. In Greece, the so-called neo-Byzantine style prevailed, which took two old schools of icon painting as its model: The icon painters of the Palaiologian period and those of the Italo-Cretan school. In Greece, however, many icons are still written in the Western manner of the Nazarene style.

Important icon painters in Russia included Feofan Grek, Andrei Rublyov, Dionisij, the painters' villages of Palech, Mstera, Choluj, as well as numerous Old Believer's studios in the Urals and on the lower Volga.

Other centers of icon painting are in Georgia, Serbia, northern Macedonia, Bulgaria, Armenia and Ethiopia. In Romania, the frescoes of the Moldavian monasteries are of high importance.

Icons are windows into the spiritual world for the Orthodox Church. This is shown by the often golden background, the two-dimensionality or false perspective and the non-naturalistic painting style. In every Orthodox church there is the iconostasis, a wooden wall decorated with icons with, if the church is large enough for it, three doors between the faithful and the altar. In churches with only a single-door iconostasis, the altar space thus separated also assumes the function of the western sacristy. In large churches, the deacon's office serves as such, the space behind the southernmost door, assuming the church's easting. In the center, as seen from the viewer, to the right of the central door hangs an icon of Christ, to the left an icon of the God-bearer, between them the royal door through which the priest brings the King of honors to the congregation in the Gospel book and in the Eucharist. During the Eucharist, this door is open and the altar is thus visible. When the priest is not carrying the Gospel or the chalice of the Eucharist, or when another person enters the sanctuary, one of the two outer doors is used.

Icons are venerated by crossing oneself before them, bowing or throwing oneself to the ground and kissing them (but not on the face of the depicted figure), thus merely greeting them reverently. This worship is strictly distinguished from the worship that is only due to God. Also, according to Orthodox doctrine, worship refers to the sitter, not to the icon itself as an object of wood and paint. Statues of saints, on the other hand, are rejected, especially since the ancient Greeks had used statues a lot in their religion and therefore identified them with idols.

Most Orthodox also have icons at home, often arranged in a "prayer corner" in the living room, on the east wall if possible. The design of such prayer corners varies in different Orthodox cultures.

Yaroslavl' and Pskov are often missing from the list of important "icon painting schools". Vladimir belongs to them more or less. Novgorod, Tver and Pskov play a major role especially in the early period and until the 16th century, Moscow (armory) and Yaroslavl' still until the beginning of the 18th century. After that, other workshops are important, such as Palech and Choluj. Among the Old Believers' workshops, Nev'jansk is the most important in the Urals. Also in the painting village of Mstera mainly Old Believer icon painters worked. Many of the icons, which are usually attributed to Palekh because of their fine painting, come from here. Also important Old Believer workshops are the Frolov workshop in Raja, now Estonia, the workshops in Vetka, now Belarus and Syzran on the lower Volga.

Reverse of the double-sided Poganovo icon with the vision of Ezekiel, Constantinople work c. 1400, Sofia National Archaeological Museum.

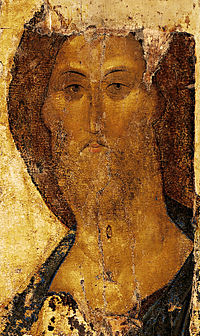

Christ by Andrei Rublyov, beginning of the 15th century

Icon painting

Icon painting to this day is based on the works of classical models. Icon painters learn their craft from experienced masters. Icon painting books are known about the painting book of the Holy Mountain Athos since the 18th century. After emigration of many Russians after the end of the First World War and the October Revolution, among the refugees were icon painters who had practiced this activity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Of these, the exiled Russians Peter Fedorov and Ivan Schneider published in Paris of the interwar period the book: "Tehnika ikonopisi" (The Technique of Icon Painting), which translated into German in 1978, became the first reference book in German. This publication was followed by other publications, which conveyed the techniques of icon painting, for which modern painting materials are also available today. In Orthodox countries, icon painting is still taught today at state institutions and private art academies, especially in the techniques of restoration of tempera paintings and ecclesiastical painting.

Technique and preliminary drawing

The main works in icon making follow a traditional sequence of activities. These are a prerequisite for the construction of the icons, which are made of different materials and layers.

Important activities are:

- Selection of the board and its processing;

- Preparation of the board for priming, sanding, glueing and fixing the canvas;

- Preparation of the painting base (levkas);

- Priming and treatment of the painting base;

- Drawing, transfer, enlargement or reduction of the drawing, tracing - "Grafija";

- Gilding of the picture surface;

- Preparation of the colors and "opening up" the icon;

- Execution of the details - Doličnoe;

- Stitch modeling of the details (Doličnoe)

- Application of the Sankir, first, second and third ockering and execution of the incarnate (Ličnoe).

- Post-treatment of the drawing and painting; coloring of the areas of the border and the edge, the halos and the inscription;

- Protection of the icon: varnishing and lacquering

Board

Image carrier of the icons is wood. The choice and cut of the boards usually followed the local conditions. Durable wood and knotless boards were preferred. Large panels were and are assembled from two or even more boards. The board of the icon is chosen mainly from resin-free tree species: Linden, alder, ash, birch, cypress, beech, sycamore or palm. Historically, boards were also taken from pine trees. Boards cut with a hatchet were found in ancient painters, later sawed wood was used. For the pre-treatment of the board, it is immersed in water at 50 °C, which serves to coagulate and eliminate proteins. Then it is dried and impregnated with sublimate to eliminate wood pests. Boards are then trimmed and the side of the image carrier is determined. The convex side is always preferred as the front side. The vertical of the icon runs parallel to the wood fibers. In order to prevent warping of the boards, which are practically always cut as a fletch, insert strips are placed at the top and bottom as cross wedges made of harder wood. The surface for the execution of the icon image is created by a recess (Kovčeg), which is 1-4 millimeters for smaller and up to 5 millimeters for larger icons.

Fabrics

Fabrics come into question as a support material for icons in two ways. First, fabrics were used to cover joints in assembled wooden panels. Secondly, the entire wooden panel was soon covered with fabric to create a buffer layer between the shrinking or expanding layer of wood due to weathering and humidity and the only moderately movable primer with the layer of paint on top. This prevents cracks and similar consequences. Primarily, therefore, a fabric is the actual support of the painting with wooden panel needed for mechanical support and consolidation. The connection of canvas and wooden panel requires a correspondingly flexible primer as the actual painting base.

Primer

The icons are primed with special plaster or chalk primer. Plaster or chalk is mixed with glue and applied to the pre-glued image carrier material in several thin layers, which should be sanded or smoothed either individually or as a whole. The thickness of the layer and the amount of glue should vary from layer to layer in order to achieve the most coherent and also resistant primer. Color pigments, usually white, can also be added to the top layers or applied as a base coat on top. Bolus red can also be applied to surfaces intended for gilding. The relevant recipes are summarized in the painter's book of Athos:

- Extraction and preparation of the glue;

- Preparation of the plaster;

- Preparation and application of the plaster base;

- Preparation and order of the bolus for gilding and the gilding itself

Icon collections and museums

In Germany

- The Sculpture Collection and Museum of Byzantine Art in Berlin has the first-rate collection in Germany of Late Antique and Byzantine art from the 3rd to 15th centuries. Among them are some worldwide rare preserved mosaic icons.

- The Icon Museum in Recklinghausen, opened in 1956, is the most important museum of Eastern Church art outside the Orthodox countries. The central part of the collection comes from the collection of Alexandre Popoff, who founded the world's largest private Russian art collection in 1920 in Paris opposite the Elysée Palace in the "Galerie Popoff". With funds from the WDR and the government of North Rhine-Westphalia, and against the interests of the Louvre and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Popoff's collection of 50 Russian icons was secured for the museum in 1967 for DM 600,000. More than 3,000 icons, embroideries, miniatures, woodwork and metalwork from Russia, Greece and other Balkan states provide a comprehensive overview of the diverse themes and stylistic development of icon painting and small-scale art in the Christian East. A wood-carved iconostasis gives an idea of the location of icons in Orthodox churches. The Coptic section of the Icon Museum documents the transition from pagan late antiquity to early Christianity in Egypt with outstanding works. Reliefs made of wood and stone, as well as various fabrics, glasses, bronzes and crosses, and some mummy portraits testify to the diversity of artistic activity in Egypt from the 1st century to the early Middle Ages.

- The Icon Museum of the City of Frankfurt am Main, opened in 1990, forms the eastern end of the Frankfurt Museum Embankment. It is located in the Deutschordenshaus. The newly designed interiors of the museum were designed by the Cologne star architect Oswald Ungers. The museum is the result of a donation by Jörgen Schmidt-Voigt, a physician from Königstein, who donated about 800 icons to the city of Frankfurt in 1988. The collection, which dates from the 16th to the 19th centuries, was gradually expanded to over 1000 exhibits through systematic purchases, loans or donations. The most significant expansion of the collection took place in 1999, when the Icon Museum received 82 post-Byzantine exhibits on permanent loan from the icon collection of the Museum of Byzantine Art in Berlin.

- The icon collection in the Schlossmuseum Weimar: After Goethe's early efforts to acquire "Russian images of saints" for the Weimar grand ducal art collections, it was not until the 1920/30s that the merchant and lawyer Georg Haar began to build up a private collection of mainly Russian icons in Weimar. By the time of his suicide in 1945, the collection in the Haar villa on the edge of the Ilm Park had grown to about 100 painted wooden icons and cast metal icons from the 15th to 19th centuries. It was finally transferred to the Weimar Palace Museum by testamentary disposition. Among the outstanding examples of Russian icon painting are the so-called royal door of a picture wall (iconostasis) from the Novgorod School (15th century) and a large-scale icon depicting the Nativity of Christ from the Moscow School (15th century). Stylistic and iconographic diversity make the special charm of the Weimar icon collection.

- The Landesmuseum Mainz houses a collection of 160 icons belonging to Prince Johann Georg von Sachsen. The prince himself respected them as a centerpiece of his interests, including scientific ones. He devoted several individual studies to the icons in his writings. All the icons in the prince's collection are post-Byzantine. Few pieces date as late as the 16th century, but the majority of the icons were created between the 17th and 19th centuries.

- The Museum im Alten Schloss Schleißheim, a branch museum of the Bavarian National Museum in Munich, houses about 50 wooden icons, mainly from the 19th century and from predominantly Russian provenances, plus about twice as many metal icons. The icons are part of the ecumenical Gertrud Weinhold Collection, which was transferred to the Free State of Bavaria in 1986. In 2000, the house received an icon donation of about a dozen and a half pieces from private hands with Russian icons from the 17th to 19th centuries.

- Many diocesan museums also house icons, including the Diözesanmuseum Freising and Kolumba in Cologne.

- At Autenried Castle in Ichenhausen near Günzburg there is an icon museum (founded in 1959) under the sponsorship of the Slavic Institute in Munich and the German Orthodox Church. This houses Greek Orthodox art from the 16th century to modern times.

- From 1932 until his death in 1946, Emilios Velimezis collected icons for the Benaki Museum. Parts of this collection have been exhibited several times in German-speaking countries, including the Recklinghausen Icon Museum (1998), the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna (2007) and the Pergamon Museum in Berlin (2007).

- Russian and Greek icons as well as Romanian reverse glass icons from the collection of Joachim and Marianne Nentwig are on display in the Mildenburg Museum in Miltenberg.

In Russia

- The Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow has the world's best collection of Russian art. It holds icons by Russian icon painter Andrei Rublyov, as well as a large collection of icons from the 12th to 17th centuries. The most valuable exhibit is the Byzantine icon of the Mother of God of Vladimir.

- The Hermitage in Saint Petersburg houses a large collection of Russian icons, which are kept in the Collection of Russian Culture and Art.

In Sweden

- The Swedish National Museum, Stockholm, has one of the best-known and best collections of its kind outside the Russian republics, with over three hundred mainly Old Russian icons from the 14th/15th to the 19th centuries.

In Switzerland

- The Musée Alexis Forel in Morges on Lake Geneva has a collection of 130 icons, mostly from Russia (Jean-Pierre Müller Foundation), which are exhibited in changing sections.

- The Musée d'art et d'histoire in Geneva has a collection of icons comprising several dozen pieces. It is published monographically and is part of the display collection.

- The icon collection of Urs Peter Haemmerli at the Museum Burghalde in Lenzburg is the largest permanently exhibited icon collection in Switzerland. It comprises around 65 Russian panels from the 16th to the 19th century.

In the Netherlands

- The Icon Museum in Kampen, the Netherlands, opened in 2005. The Alexander Foundation for Russian Orthodox Art was created to secure collections of icons from private collections for the future and make them accessible to the public. In 2013, the Stefan Jeckel collection was acquired. The collection consists of 1723 metal icons. It is one of the largest collections of travel and metal icons in the world.

In England

- The British Museum in London has a collection of just over 100 icons from Byzantium, Greece and Russia. The largest group is made up of 72 Russian icons.

In Greece

- The icon collection of the Byzantine and Christian Museum in Athens includes about 3000 pieces.

- Some of the monasteries of Mount Athos have significant collections of icons. For example, Hilandar Monastery has 3500 icons, 1500 of them from the Middle Ages.

The exhibition hall of the Treasury in the new library of Hilandar Monastery displays ten Byzantine Deësis icons of the 13th century, which once belonged to eleven Deesis icons of the iconostasis. It includes the Mother of God Hodegetria, considered a masterpiece in art history, which originally stood in the old iconostasis, as well as a mosaic icon of the Mother of God Hodegetria from the 12th century as the central display piece. In addition to the large number of Greek-Byzantine icons, the "Bogorodica Neoboriva stena" of Serbian provenance, which is legendarily associated with the Battle of the Field of Blackbirds, is significant. The most venerated is the Mother of God Tricheirousa, who is kept next to the abbot's chair in the naos, the church, and is an essential pilgrimage object of the monastery. She is the most important icon of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

In Italy

- The largest existing collection of 77 Epirotic icons in Central Europe is located in the Church of Santa Maria Assunta in Villa Badessa, a fraction of the Italian municipality of Rosciano in Abruzzo. In 1965 the icons, "written" between the 15th and 20th centuries, were declared "works of national interest" by the Italian Ministry of Public Education.

- Museo Comunale delle Icone e della Tradizione Bizantina (Municipal Museum of Icons and Byzantine Tradition) in Frascineto in the province of Cosenza in Calabria. The museum houses the private collection of archimandrite Fr. Paolo Lombardo. After the reopening on April 19, 2017, the collection counts about 600 Greek and Russian icons written between the 18th and 20th centuries.

In Serbia

- The icon collection of the Serbian National Museum in Belgrade includes icons from the 12th to the 18th century, with emphasis on the 14th century. In particular, the double-sided icon depicting the Madonna Hodegeteria and the Annunciation, as well as Zograf Longin's icon of Saints Sava and Simeon are significant.

- The Museum of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the Patriarchal Seat in Belgrade has the most significant collection of liturgical and historical exhibits of the Middle Ages from Serbia, in which the icons of the re-establishment of the Patriarchate of Peć in 1557 are especially significant.

In North Macedonia

- The Ohrid Icon Museum is one of the most important in the world. It houses one of the most important collections of icons of the Palaiological Renaissance. Among them are a number of large-sized double-sided icons of Mary and Christ with silver fittings, as well as the famous depiction of the Ohrid Annunciation of Mary from the first half of the 14th century.

In Bulgaria

- In particular, in the collection of the Archaeological Museum in Sofia there is the double-sided Poganovo icon, which comes from imperial workshops of Constantinople or Thessaloniki.

In Egypt

- St. Catherine's Monastery in Sinai has the largest Byzantine icon collection in the world, which also preserves icons made before iconoclasm. The 13th century icon of Archangel Gabriel is considered a masterpiece of Byzantine art. The icon of Christ Pantocrator from the 6th century, made in encaustic technique, is one of the oldest of its kind.

In the United States

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art maintains one of the most comprehensive collections of medieval art at The Met Cloisters. One of the main focuses is the art from Byzantium of the period from the 5th to the 15th century.

- The Museum of Russian Icons in Clinton, Massachusetts, is a nonprofit art museum. The collection includes more than 1000 Russian icons and related works of art. This makes it one of the largest private collections of Russian icons outside of Russia and the largest in North America. The icons in the collection range from the 15th century to the present.

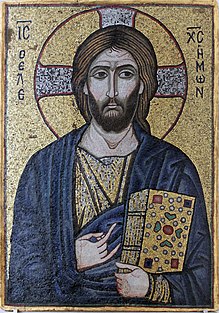

Mosaic icon "Christ the Merciful", 12th century. Byzantine Museum, Berlin

One of the largest collections of icons of the Middle Ages with icons from the 12th to the 15th century has the Hilandar Monastery on Mount Athos. The Mother of God Hodegetria is one of the major works of European panel painting. Hilandar, 13th century

Archangel Gabriel, Constantinople or Sinai, 13th century.

The icon at the tomb of St. Nicholas in Bari is a gift of the Serbian king Stefan Uroš III Dečanski, around 1330.

A masterpiece of the Palaiological Renaissance is the Ohrid Annunciation of the Virgin Mary, first half of the 14th century.

01.jpg)

Icon of the Hodegetria (15th century) in the altar room (Bema) in the Chiesa Santa Maria Assunta in Villa Badessa

Derived terms

- Iconoclasm: destruction of sacred images

- Iconolatry: image worship

- Iconography: scientific interpretation of artistic motifs

- Iconographic saint attribute: characteristic accessory of depicted saints

- Iconology: scientific interpretation of symbolic forms

- Iconostasis: wall decorated with images in Orthodox churches

- Icon: similar images

- Icon: Pictograms in computer user interfaces

Special icons

- Resurrection icon

- Trinity icon

- Marian icon

Questions and Answers

Q: What is an icon?

A: An icon is an image or representation that has a religious meaning.

Q: What does the word icon primarily refer to within Christianity?

A: Within Christianity, the word icon most often refers to a painting on a wooden panel that has been done in the Orthodox Christian tradition.

Q: What are some materials that an icon might be made of?

A: An icon might be made of carved ivory panels or panels of silver or gold.

Q: Whom might an icon depict?

A: An icon might depict a holy being such as Jesus, Mary, a saint, or an angel.

Q: What might an icon depict from the Bible?

A: An icon might depict scenes from the Bible, such as the Crucifixion.

Q: What is the purpose of an icon in Orthodox Christianity?

A: In Orthodox Christianity, an icon is thought of as a window through which a person can get a view of God's truth.

Q: Can the word icon be used to describe images of other religions?

A: Yes, although the word icon is most often used to describe Christian images, it can be used to describe images of other religions as well.

Search within the encyclopedia