Hyrax

The Schliefer (Procaviidae) are a family within the order of the same name in German Hyracoidea. They are members of the mammals, well rabbit-sized and in external appearance reminiscent of marmots. Their body and limbs are strong, the snout is short and the tail is hidden in the fur. A characteristic formation is found on the back, where a conspicuous colored spot marks a gland. Also conspicuous are the numerous tactile hairs, which occur not only on the face, but distributed over the entire body. The animals occur endemically in Africa, as the only exception the Klippschliefer lives also in Near East. The cliff and bush sheep inhabit rocky, open and partly dry areas, whereas the tree sheep are adapted to forests. The habitat of the Schliefer includes lowlands as well as high mountainous areas.

The animals can climb well and are fast on steep, uneven or slippery terrain due to some adaptations on their feet. The ground-dwelling cliff and bush sheep live diurnally and form large family groups. In contrast, the tree-dwelling tree shags are nocturnal and largely solitary. All species are territorial and the loud calls of the males are significant. The main food of the tree shags consists of plants, the individual species differ in their preference for harder or softer components. Water is rarely drunk. Breeding usually occurs once a year. Females have a very long gestation period. A litter contains one to four young.

The order of the Schliefer is relatively old, the earliest representatives are already in the Eocene almost 50 million years ago in both northern and southern Africa. In contrast to today's Schliefern, the original forms were very varied. In addition to small animals, giant ones weighing over a ton also occurred. The original Schliefern moved in the most different ways running, jumping or climbing. Thus they occupied a variety of habitats. By the Miocene at the latest, the Schliefer also reached Eurasia and spread widely across both continents. However, the high variability was subsequently lost due to competition with other animal groups, mainly the ungulates. Only the small representatives of the modern Schliefer survived until today. Due to their partly abundant fossil finds and the numerous recorded forms, the extinct Schliefer are of great importance for the biostratigraphy of Africa.

The closest relatives of the sheep are the proboscideans and manatees. All three orders are grouped together as Paenungulata, which in turn form part of the very heterogeneous group Afrotheria. However, the exact relationships of the shurries to other mammals were unclear for a long time. In the 18th century, when the first natural history accounts of the sheepskin were written, they were thought to be rodents. Later, they were often associated with various ungulate groups. This resulted in an intense debate that took place throughout the 20th century, debating their relationships. On the one hand, scientists saw a connection of the sheepherders to the odd-toed ungulates, on the other hand to the elephants. The dispute could only be resolved in the transition to the 21st century with the advent of biochemical and molecular genetic investigation methods. The scientific naming of the family took place in 1892, the order name had already been coined in 1869. The population of the individual species is classified as not endangered, with one exception.

Features

Habitus

Today's sheep shivers are relatively small mammals about the size of a rabbit. Their head-torso length is between 32 and 60 cm. The tail is tiny and usually barely visible, at most 3 cm long. Shivers reach a weight of 1.3 to 5.4 kg. Differences between males and females are not pronounced. Across the range, however, considerable variations in size can be observed within a species, some of which are due to environmental factors. Externally, today's sheepdogs resemble guinea pigs. They are very robust, stocky animals, all characterized by a muscular, short neck and a long, upwardly curved body. Their coat coloration varies by genus and species, ranging from gray to light and dark brown to black, and often the belly appears lighter. On the back, a gland is covered by a patch of fur of a different colour. Animals of dry landscapes have a short coat, inhabitants of forests and alpine highlands, however, have a long and dense coat. It is interspersed with numerous vibrissae, up to 30 mm in length. Further, with up to 90 mm particularly long touch hairs appear in the face. The head of the Schliefer is flattened, the snout is generally short, as are the ears. The upper lip is split. The eyes bulge forward, they have an additional lid that slides from the iris over the pupil in bright sunlight and is called the umbraculum. It enables the Schliefern to look into the sun. Sometimes bright spots appear on the face, for example on the eyebrows. The limbs are short, ending in four toes in front, which bear small hooves. The hind legs have three toes, the innermost of which has a curved claw, while the others also have hooves. The toes and fingers are united up to the base of the last limb. The bare, often dark soles are penetrated by numerous glands.

Skull and dentition characteristics

The skull of the Schliefer is relatively generalized with a broad and flat forehead line, a vertically erect occipital bone and projecting zygomatic arches. In lateral view it reaches a relatively great height, more than half of which is occupied by the massive lower jaw. The rostrum is short and ends bluntly. On the parietal bones there are distinct temporal lines, which in the Klippschliefer (Procavia) can unite to form a parietal crest, which, however, is not particularly massive. A prominent bone is the Os interparietale, an element of the skull roof between the two parietal bones and the occipital bone. Depending on the species, a postorbital arch may be formed, closing the posterior margin of the orbit. This is the case, for example, in the tree-shamblers (Dendrohyrax), but not in the clip-shamblers and bush-shamblers (Heterohyrax). As a unique feature of the Schliefer, the parietal bone participates at the end of the posterior margin of the eye. The lacrimal bone forms part of the orbit. At the base of the skull, the glenoid fossa for the joint of the mandible is formed by both the zygomatic and temporal bones. The mandible is most conspicuous for its massive and broad as well as high ascending branch. The crown process rises only slightly above the articular process. At the rear end the angular process is clearly rounded.

The dentition of the modern Schliefer has a somewhat reduced number of teeth, which mainly affects the front teeth. It consists of a total of 34 teeth with the following dental formula:

Skeletal features

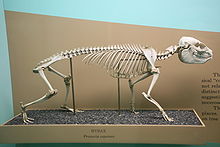

Individual peculiarities are also found in the skeletal structure. The spine consists of 7 cervical, 19 to 22 thoracic, 6 to 9 lumbar, 5 to 7 sacral, and 4 to 10 caudal vertebrae. As is common in Afrotheria, the number of dorsal vertebrae (thoracic and lumbar) is higher than in other related groups, ranging from 27 to 30; within Afrotheria, shivers have the most single vertebrae. The lumbar spine is markedly elongated, reaching 10 cm in length, more than half the length of the thoracic spine, which measures about 15 cm. Between 19 and 22 pairs of ribs occur, with 21 and 22 being more common. Of these, seven to eight pairs are connected to the sternum. A clavicle is not developed. The scapula also lacks an acrominion, with the shoulderbone gradually tapering out instead. The ulna and radius are about the same length and rotated around each other. The ilium is extremely cephalad-extended, the pelvic segment in front of the acetabulum thus occupying a good double of the remaining pelvic length. A third rolling mound occurs on the femur, usually formed only as a weak ripple. The fibula is connected to the tibia at its base by ligaments.

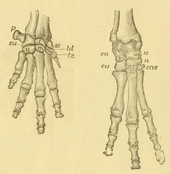

The carpal and tarsal bones show a serial (taxeopod) arrangement, that is, the individual root bones of each row lie one behind the other and do not overlap each other. Thus, at the carpus the capitate bone is directly connected to the lunate bone, at the tarsus the talus bone is only connected to the navicular bone and the calcaneus bone is only connected to the cuboid bone. The talus is firmly fixed by the two lateral malleoli. Due to the special construction of the limbs, the Shliefer are not able to rotate hands and feet in the joint area, this occurs mainly in the area between the root bones, in the case of the hand additionally by rotation of the shoulder joint. The hand has five rays (I to V), of which the thumb (ray I) is rudimentary and remains hidden under the skin. The external ray (V) is also reduced in size. In the foot there are three rays (II to IV). In both the hand and the foot the principal axis passes through the third ray in each case, giving rise to a mesaxonic structure.

Glands and tactile hair

A rather unusual formation is the dorsal gland of the Schliefer, which is a bare skin surface surrounded by a distinctively coloured patch of hair. The gland has lengths of about 1.5 cm and consists of seven or eight lobules of glandular tissue located deep in the skin. Each individual lobule contains 25 to 40 compartments filled with secretory epithelium, which in turn surrounds an irregularly shaped cavity. From here, well-developed ducts lead to the surface. The lobules swell, especially in sexually active animals, irrespective of sex. The hairs of the coloured patch around the gland normally lie flat according to the rest of the coat and cover the gland. However, they can become erect when excited and then form a conspicuous tuft that exposes the gland.

Further glands are found on the soles of the hands and feet. The sheep do not walk on their hooves, but on their bare soles, which are covered by an epithelial layer about 1 cm thick. Within this are glands that penetrate the skin layer in high density with about 300 glandular ducts per square centimeter. The individual glands are about 15 to 45 μm in diameter and are surrounded by fatty and connective tissue. In principle, the glands resemble those of primates, the cells being light or dark in color. The latter are the actual producers of secretions and contain the Golgi apparatus. They produce glycoproteins. The secretions keep the soles of the hands and feet constantly moist. Combined with the muscular force that pulls the soles in along the central callus cleft, the animals produce a high adhesive force that enables them to climb trees and rocks or walk over smooth, slippery, and uneven surfaces.

A special feature of the sheep is the distribution of tactile hairs not only on the face, but regularly over the entire body. This feature occurs only rarely in other mammal groups, it is known for example from the manatees. The individual tactile hairs are black in colour and longer than the rest of the hairs. At the base they show the typical structure of sensory hairs with the hair bellows and the surrounding blood sinus, which are enclosed in a capsule of connective tissue. The entire structure of the base is elongated compared to that of other hairs and is interspersed with numerous nerves that terminate at the hair bellows. The skin around the capsule is in turn rich in blood vessels and enriched with fibrous tissue. The tactile hairs serve the orientation of the animals in narrow caves, rock chambers and passages.

Soft Tissue Anatomy

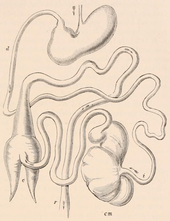

The digestive tract is relatively complex, but not as much as in some cloven-hoofed groups. The stomach has two chambers and thus divides into two functional parts. The anterior section has no glands and functions primarily as a food reservoir. In contrast, the posterior section with the gastric portal is gland-rich. The connecting small intestine grows up to 130 cm in length, and opens into the appendix. This has an unusual structure in that it consists of an anterior undivided chamber and a posterior sac-like structure (also called the "intestinal sac") with two conical appendages; both parts of the appendix are connected by a section of intestine 11 to 20 cm long. The anterior appendix section serves as a fermentation chamber and produces a greater amount of volatile fatty acids. In the posterior sac-like chamber, digestive residues are slowly mixed. The liver is highly subdivided, and there is no gall bladder. The tongue has a length of about 5 cm. Its surface consists of filiform mechanical and fungiform and foliform taste papillae. The filiform papillae of the tip of the tongue have a shovel-shaped process. Fungiform papillae are distributed along the edges of the tongue and on the underside of the tongue tip. On the body of the tongue, on the other hand, leaf-shaped papillae occur, and in addition some dome-shaped papillae are formed here. Salivary glands are often found at the root of the tongue.

Females have a paired (cliff sheep) or two-horned (tree and bush sheep) uterus. They usually have one to three pairs of teats. The number is generally smaller in tree sheep and the position of the teats is variably distributed between the thoracic and inguinal regions. In the bush sheep and the klip sheep, one pair often occurs in the thoracic region and two in the inguinal region. The testes of males are hidden in the abdominal cavity. They weigh between 1.0 and 1.65 g in sexually inactive animals. The penis has a different structure in the different genera. In the tree sheep it has a simple, slightly curved shape, in the klip sheep it is short, elliptical in shape and thickens slightly upwards, while in the bush sheep it has an appendage with the opening of the urinary tract. The differing distance to the anus is also striking, which is shortest in the tree sheep with an average of 1.7 to 2.5 cm and longest in the bush sheep with 8.0 cm. The Klippschliefer lies with values around 3.5 cm in between.

Schliefer have two muscle groups that run to the tip of the nose. They do not form larger tendons and are only well separated from each other in their front section. Both muscles move the nose, but this can only be done to a limited extent. The masticatory apparatus of the sheep-dog resembles that of herbivorous ungulates. It shows a dominance of the masseter over the temporalis muscle complex, which is also indicated by the high position of the mandibular joint and the extended angular process. However, in contrast to many herbivores, the temporalis muscle is relatively larger in the Schliefern. This is accompanied by a relatively short snout. On the one hand, the animals are therefore capable of more complex chewing movements like hoofed animals, but they can also put more force into the anterior dentition. The short crown process means that the mouth can be opened wide, for example to present the upper pointed incisors.

Schematic representation of the digestive tract of a Schliefer; d: duodenum; i: hip intestine; cm: appendix; c: additional appendix ("intestinal sac"); r: rectum; not to scale

_fur_skin.jpg)

Fur of the mountain forest treecreeper (Dendrohyrax validus) with visible light spot

Hand (left) and foot (right) of a Schliefer, the taxeopode (serial) arrangement of the hand and tarsal bones is clearly visible.

Rainforest tree shag (Dendrohyrax dorsalis)

Skull of the Klippschliefer (Procavia capensis)

Skeleton of the clip-on sleeper

Distribution and habitat

The Schliefer are largely endemic to Africa. An exception is the Klippschliefer, which also occurs in the Near East, especially in the Levant and on the Arabian Peninsula. Away from this occurrence, both the cliff and bush sheep live predominantly in the eastern and southern parts of Africa. They often prefer rocky, arid areas, but can also be found in savanna and forest landscapes where rocky areas or various rock formations are available. Both species sometimes occur sympatrically. Tree shags, on the other hand, are largely restricted to forests. Their distribution ranges from western to central to eastern Africa, and scatters from here to the southern part of the continent. The various species can be observed in the lowlands as well as in the mountains up to altitudes of 4500 m in some cases. The presence and abundance of sloths in a given region is influenced by external conditions. Abiotic factors include, for example, temperature and precipitation as well as the frequency of caves and hiding places. Biotic factors refer to the abundance of predators or parasites, but also to intra- and supra-species competition for food resources.

Search within the encyclopedia