Hyperglycemia

![]()

This article discusses hyperglycemia in human medicine; for hyperglycemia in veterinary medicine, see the article on canine and feline diabetes mellitus.

Hyperglycaemia (ancient Greek ὑπέρ hyper "over", γλυκύς glykys "sweet" and αἷμα haima "blood", colloquially also excess sugar) is an abnormally increased amount of glucose in the blood (blood sugar). Acute hyperglycaemia is reflected in the glucose level, long-term hyperglycaemia in the HbA1c level of the blood.

Hyperglycemia is the leading symptom of diabetes mellitus (diabetes), in which the necessary regulation of the nutrient glucose is disturbed, so that it is also excreted in the urine above a level of about 180 mg/dl, the so-called renal threshold. The short-term symptoms of hyperglycaemia range from a feeling of thirst and dry mouth to increased urine excretion (polyuria), visual disturbances and hyperglycaemic coma, which can be fatal if left untreated. In the long term, hyperglycaemia plays a major role in the classic consequences of diabetes, such as stroke, loss of vision or kidney weakness. Its treatment consists of regulating the glucose level in the blood by means of appropriate measures, such as the administration of insulin.

The term hyperglycemia was defined differently. For example, until the end of the 19th century, medicine assumed that any presence of sugar in the blood had to be regarded as pathological. In 1885, it was recognized that sugar also occurs in the blood of healthy individuals and that only at a level of about 210 to 260 mg/dl is increased urine excretion the sign of a disease. According to today's definition, the blood sugar level in healthy people does not exceed 100 mg/dl when fasting and does not exceed 140 mg/dl after a sugar load test (oGTT). In diabetics, it is above 125 mg/dl when fasting and above 200 mg/dl when oGTT. The "grey area" in between is also known as intermediate hyperglycaemia and statistically carries an increased risk of developing diabetes mellitus.

Occurrence

The blood glucose level in healthy people should be below 100 mg/dl when fasting (i.e. at least 8 hours after the last calorie intake) and below 140 mg/dl after a sugar load test. When the body consumes food, glucose and other sugars, with a few exceptions, are absorbed through the intestine and passed through the portal vein (enterohepatic) circulation to the liver before entering the blood. Various regulatory mechanisms keep the blood glucose level there constant at around 70 to 80 mg/dl in the long term in healthy individuals. If the glucose level in the enterohepatic circulation increases as a result of a carbohydrate-rich food intake, the beta cells of the pancreas are stimulated to secrete the blood sugar-lowering hormone insulin in order to keep the glucose level in the blood constant. If this regulation fails or the insulin loses its effect, short- or long-term hyperglycemia occurs.

Hyperglycemia is the leading symptom of diabetes mellitus, but is not a definite criterion for it. It can also be triggered by Cushing's disease (increased cortisone levels), acromegaly (increased growth hormone levels), pheochromocytoma (increased levels of adrenaline and noradrenaline), hyperthyroidism (for example as a result of Graves' disease), iron deposits in the beta cells of the pancreas (haemochromatosis) and medication. It can also occur with infections, after a heart attack, stroke or anaesthesia. In bitches, high levels of progesterone in the inter-estrus period can cause a rise in blood glucose levels, and in cats, stress can trigger prolonged hyperglycaemia.

Origin

There are different reasons why the body cannot stabilize the blood glucose level in the physiological range. The most common causes of an increase in blood glucose levels are a reduced response of sugar-storing cells such as fat and muscle cells to insulin (insulin resistance) due to overconsumption of carbohydrates and sugar or a reduced insulin secretion by the pancreas. In the former case, insulin secretion may even be increased. Therefore, the World Health Organization advises a sugar tax to achieve a noticeable decrease in sugar consumption so that fewer people suffer from overweight, obesity and diabetes.

The level of growth hormone (somatropin) is only increased in healthy people when insulin levels are too low. It increases blood sugar levels by both inhibiting the uptake of sugar into fat and muscle cells and reducing sugar consumption by increasing the supply of fats (fatty acid oxidation), particularly in muscle. If both hormones are elevated, hyperglycemia can occur because the blood sugar-lowering effect of insulin on the sugar-storing cells is then limited.

Cortisol increases the blood sugar level. In particular, it stimulates the formation of new sugar in the body and at the same time reduces sugar consumption. Therefore, it counteracts the blood sugar-lowering insulin. If there is an excess of cortisol (Cushing's syndrome, stress), the blood sugar level rises.

Adrenaline and noradrenaline simultaneously lead to increased new formation and release of glucose as well as to an inhibition of insulin secretion. Increased levels, such as those found in pheochromocytoma, lead to hyperglycemia.

In hyperthyroidism glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis are stimulated, in hemochromatosis the increased iron level in the pancreas leads to siderosis and fibrosis, whereby the function of the insulin-producing beta cells is then also impaired. In glucagonoma, increased glucagon levels cause an increase in gluconeogenesis with a simultaneous decrease in glycogenolysis and glucose consumption.

Serious illnesses such as myocardial infarction, severe infections or trauma can cause hyperglycaemia, as can anaesthesia. The cause is the post-aggression metabolism triggered by this, in which peripheral insulin resistance occurs, whereby the administration of insulin then also does not lead to a sufficient lowering of the blood glucose level. A special case of morning hyperglycemia during ongoing insulin therapy is the Somogyi effect: The Somogyi effect, in which, for example, as a result of excessive evening insulin administration, nocturnal hypoglycemia and subsequent reactive hyperglycemia occur. The Dawn phenomenon is the term used to describe hyperglycaemia that occurs when the increased insulin requirement in the second half of the night is not compensated for as a result of the increased GH excretion at this time, for example as a result of the nocturnal drop in effect of a long-acting insulin after it has been administered once in the morning.

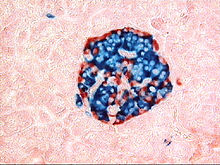

Islets of Langerhans of the pancreas (insulin marked in blue and glucagon in red. The diameter of the islet is 0.2 to 0.5 mm).

Search within the encyclopedia