Hypatia

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Hypatia (disambiguation).

Hypatia (also Hypatia of Alexandria, Greek Ὑπατία Hypatía; * c. 355 in Alexandria; † March 415 or March 416 in Alexandria) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer and philosopher of late antiquity. Nothing of her works has survived, and details of her teachings are not known. She taught in public and advocated a Neoplatonism that was probably enriched with Cynic ideas. As a representative of a non-Christian philosophical tradition, she belonged to the oppressed pagan minority in predominantly Christian Alexandria. Nevertheless, she was able to teach unchallenged for a long time and enjoyed a high reputation. Eventually, however, she became the victim of a political power struggle in which the church teacher Cyril of Alexandria instrumentalized religious antagonisms. An incited mob of Christian lay brothers and monks finally took her to a church and murdered her there. The body was dismembered.

Hypatia was remembered by posterity mainly for the spectacular circumstances of her murder. Since the 18th century, the case of pagan persecution has often been cited by critics of the Church as an example of intolerance and hostility to science. From a feminist perspective, the philosopher appears as an early representative of emancipated womanhood endowed with superior knowledge and a victim of misogynistic attitudes on the part of her opponents. Modern non-scientific representations and fictional adaptations of the material paint a picture that embellishes and in some cases greatly alters the sparse ancient tradition.

Even before Hypatia there was a woman who, according to the testimony of Pappos, taught mathematics in Alexandria, Pandrosion.

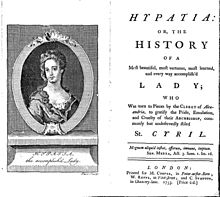

Frontispiece and title page of John Toland's anti-Catholic treatise Hypatia: Or the History of a most beautiful, most vertuous, most learned, and every way accomplish'd Lady

Life

Hypatia's father was the astronomer and mathematician Theon of Alexandria, the last scientist known by name in the Museion of Alexandria, a famous state-funded research institution. It is likely that Hypatia was born around 355, for at the time of her death, as the chronicler John Malalas reports, she was already an "old woman," probably about sixty years of age. She seems to have spent the whole of her life in her native city of Alexandria. With her father she received a mathematical and astronomical education. Later she took part in his astronomical work. Who her philosophy teacher was is unknown; according to one research hypothesis, Antoninos, a son of the philosopher Sosipatra, comes into consideration.

After completing her education, she began teaching mathematics and philosophy herself. According to the Suda, she combined rhetorical talent with a prudent, thoughtful approach. Socrates of Constantinople reports that listeners came to her from everywhere. Some of her students were Christians. The most famous of these was Synesios, who studied both philosophy and astronomy with her in the last decade of the 4th century. Damaskios reports that Hypatia wore the philosopher's mantle (tríbōn) and went about the city teaching publicly and expounding the teachings of Plato or Aristotle, or indeed any other philosopher, to all who would listen. How this message is to be interpreted is a matter of controversy among scholars. In any case, it does not support the view that Hypatia held a publicly funded chair; there is no evidence for this. Étienne Évrard interprets Damaskios' formulation in terms of teaching in the open. The surviving account of Hypatia's way of teaching places the philosopher outwardly close to Cynicism, as does the reference to her philosopher's cloak, an article of clothing that people tended to associate with Cynics.

Damaskios lets it be known that he disapproved of Hypatia's public appearance. He believed that philosophy instruction should not be given in public and not to everyone, but only to suitably qualified students. He may have been caricaturally exaggerating in his account of Hypatia's activities. In any case, it can be inferred from his words that she presented philosophical topics, which were otherwise discussed in a closed circle among the relevantly educated, to a relatively broad public.

An anecdote handed down in the Suda points in this direction, according to which she showed her menstrual blood to a student in love with her as a symbol of the impurity of the material world, in order to show him drastically the questionability of his sexual desire. Disdain for the body and bodily needs was a hallmark of the Neoplatonic worldview. Although the anecdote may have originated in the process of legend-making, it may have a kernel of truth; in any case, Hypatia was known not to shy away from deliberately provocative behavior. This is also an indication of a Cynic element in her philosophical attitude: Cynics used to shock in a calculated way in order to bring about insights.

In addition to the teaching material that Hypatia imparted to the public, there were also secret teachings that were to be reserved for a narrower circle of students. This is evident from the correspondence of Synesius, who repeatedly reminds his friend and fellow student Herculianos of the commandment of secrecy (echemythía) and accuses Herculianos of not having kept to it. In doing so, Synesios refers to the Pythagoreans' commandment of silence; the imparting of secret knowledge to unqualified persons leads to such vain and uncomprehending listeners passing on what they have heard in a distorted form, which ultimately has the effect of discrediting philosophy in public.

Socrates of Constantinople writes that Hypatia appeared around high officials. It is certain that she belonged to the circle of the Roman prefect Orestes.

Hypatia remained unmarried all her life. The statement in the Suda that she married a philosopher named Isidoros is due to an error. Damaskios mentions her extraordinary beauty.

In the context of her scientific work, Hypatia was also concerned with measuring instruments. This is evident from Synesius' request in a letter that she send him a "hydroscope", by which a hydrometer was apparently meant. Whether the instrument for recording and describing the movements of the heavenly bodies, which Synesios had built, was constructed according to Hypatia's instructions is disputed in research.

Death

Hypatia was murdered in March 415 or March 416. The prehistory formed a primarily political and personal conflict with religious aspects, with which she probably originally had nothing to do.

Previous story

Already in the second half of the 4th century there had been strong tensions in Alexandria between parts of the Christian majority and followers of the old cults, which led to violent riots with fatalities. In the course of these conflicts the minority was increasingly pushed back. The patriarch Theophilos of Alexandria had places of worship destroyed, especially the famous Serapeum, but pagan teaching was only temporarily affected, if at all.

The religious-philosophical worldview of the educated, who held to the old religion, was a syncretistic Neoplatonism, which also integrated parts of Aristotelianism and Stoic thoughts into its worldview. These pagan Neoplatonists attempted to bridge the disparities of the traditional philosophical systems through a coherent synthesis of the philosophical traditions, thus striving for a unified doctrine as philosophical and religious truth par excellence. The only exception to the synthesis was Epicureanism, which the Neoplatonists rejected as a whole and did not regard as a legitimate variant of Greek philosophy.

Between pagan Neoplatonism and Christianity there was a contrast in content that was difficult to bridge. Only Synesius, who was both a Christian and a Neoplatonist, attempted a harmonization. In questions of conflict, however, he ultimately gave preference to Platonic philosophy over the doctrines of faith. The religiously oriented non-Christian Platonists, who created the intellectual basis for a continuation of pagan religiosity in educated circles, appeared to the Christians as prominent and persistent opponents.

However, people from this pagan milieu became victims of persecution and expulsion not because of their adherence to their religious-philosophical worldview - for example, in the teaching of conventional educational content to schoolchildren - but because of their cult practice. Since Iamblichos of Chalcis, many Neoplatonists valued and practiced theurgy, a ritual contact with the gods for the purpose of interacting with them. From the Christian point of view, this was sorcery, idolatry, and conjuring up devilish demons. Radical Christians were not willing to tolerate such practices, especially since they assumed that it was a malicious use of magic powers.

Besides the conflicts between pagans and Christian inhabitants of Alexandria, there were at the same time also among the Christians serious quarrels between followers of different theological directions as well as disputes between Jews and Christians. With it political antagonisms as well as power struggles were mixed, to whose background also personal enmities belonged.

The starting point of the events that eventually led to Hypatia's death were violent clashes between Jews and Christians that escalated and claimed many lives. Patriarch Cyril of Alexandria, who had been in office since October 412, was the nephew and successor of Theophilos, whose course of religious militancy he continued. Cyril distinguished himself at the beginning of his tenure as a radical opponent of the Jews. An agitator named Hierax, working on his behalf, fomented religious hatred. When he appeared at an event held by the prefect Orestes in the theatre, the Jews present accused him of having come only to incite a riot. Orestes, who was a Christian, but who as the highest representative of the state power had to see to internal peace, had Hierax arrested and immediately interrogated publicly under torture. Thereupon Cyril threatened the leaders of the Jews. After a night attack by the Jews, who killed many Christians in the process, Cyril organized a full-scale counterattack. His followers destroyed the synagogues and looted the houses of the Jews. Jewish residents were dispossessed and expelled from the city. However, Socrates of Constantinople's claim that all Jews living in Alexandria were affected seems to be exaggerated. There was also later a Jewish community in Alexandria. Some of the exiles returned.

John of Niciu, who describes the events from the point of view of the Patriarch's partisans, accuses Orestes of taking sides with the Jews. The latter were ready to attack and massacre Christians because they could rely on the support of the prefect.

The patriarch's high-handed action against the Jews challenged the authority of the prefect, especially since attacks on synagogues were forbidden by law. A bitter power struggle ensued between the two men, the highest representatives of the state and the church in Alexandria. In this, Cyril relied on his militia (the Parabolani). To reinforce his supporters, some five hundred violent monks arrived from the desert. Cyril had excellent relations with these militant monks, having previously lived among them for several years. In the milieu of the partly illiterate monks an anti-educational attitude and radical intolerance towards everything non-Christian prevailed; they had already actively supported the patriarch Theophilos in the persecution of religious minorities. The patriarch's partisans claimed that the prefect protected opponents of Christianity because he sympathized with them and was himself secretly a pagan. The fanatical monks openly confronted the prefect when he was out in the city and challenged him with insults. A monk named Ammonios injured Orestes by throwing a stone at his head. Thereupon almost all the prefect's companions took to flight, so that he found himself in a perilous situation. He was saved by citizens who rushed to the scene, chased away the monks and seized Ammonios. The prisoner was interrogated and died under torture. Thereupon Cyril publicly praised the courage of Ammonios, gave him the name "the admirable one" and wanted to introduce a martyr cult for him. But with this he found little approval among the Christian public, since the actual course of events of the confrontation was all too well known.

Assassination

Now Cyril or someone in his circle decided to take action against Hypatia, who was a suitable target because she was a high-profile pagan figure in the prefect's inner circle. According to the account of Socrates of Constantinople, the most credible source, the rumour was spread that Hypatia, as advisor to Orestes, was encouraging the latter to adopt an intransigent attitude and was thus thwarting a reconciliation between the spiritual and secular powers in the city. Incited by this, a band of Christian fanatics gathered under the leadership of a certain Petros, who held the rank of lector in the church, and lay in wait for Hypatia. The Christians seized the old philosopher, took her to the church of Kaisarion, stripped her naked there, and killed her with "shards" (another meaning of the word ostraka used in this context is "roof tiles"). Then they tore the body into pieces, took its parts to a place called Kinaron and burned them there.

John of Niciu presents a version which, with regard to the course of events, largely agrees with that of Socrates and only differs somewhat in detail. According to his account, Hypatia was indeed brought to the church Kaisarion, but not killed there, but dragged naked to death in the streets of the city. The result, he says, was a solidarization of the Christian population with the patriarch, since he had now exterminated the last remnant of paganism in the city. John of Niciu, whose report probably reflects the official position of the Church of Alexandria, justifies the murder by claiming that Hypatia had seduced the prefect and the city population by means of satanic sorcery. Under her influence, the prefect had stopped attending church services. John describes the lector Petros, the direct instigator of the murder, as an exemplary Christian.

Hardly credible is Damaskios' account of the antecedents, who claims that Cyril, passing by Hypatia's house by chance, noticed a crowd gathered in front of it, and thereupon, out of envy of Hypatia's popularity, decided to do away with her.

For Orestes, the murder meant a spectacular defeat and he lost much prestige in the city, since he could neither protect his philosopher friend nor punish the perpetrators. Although charges were brought against the murderers, they were without consequence. Damaskios claimed that judges and witnesses had been bribed. An envoy of the patriarch went to Constantinople to the court of the Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II in order to describe the events from Cyril's point of view. Somewhat later, however, a year and a half after Hypatia's death, the patriarch's opponents were able to deal him a severe blow, for they succeeded in gaining acceptance in Constantinople. Imperial decrees of September and October 416 stipulated that henceforth legations to the emperor bypassing the prefect would no longer be permitted, and that the patriarch's militia would be reduced in size and henceforth placed under the control of the prefect. Accordingly, this force lost the character of a militia, which the patriarch could use at will and even employ against the prefect. However, these imperial measures did not last long; already in 418 Cyril was able to regain command over his militia.

The question of whether Patriarch Kyrill instigated or at least approved the murder has long been disputed. A clear clarification is hardly possible. In any case, it can be assumed that the perpetrators could assume to act in the sense of the patriarch.

Edward Watts doubts that Petros planned Hypatia's death. Watts points out that in late antiquity there were often confrontations between prominent personalities and an angry mob, but that the mob rarely had the intention to kill. Even in Alexandria, where riots were frequent, targeted killings were rare; they had occurred twice in the 4th and 5th centuries, and both times (361 and 457) the victims were unpopular bishops. It is also possible that Petros wanted to intimidate the old philosopher into withdrawing from her advisory role to Orestes, but the situation then got out of hand.

Cyril of Alexandria (Icon)

Theophilos standing triumphantly on the Serapeum (late antique book illustration)

Questions and Answers

Q: Who was Hypatia?

A: Hypatia was a mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher who lived around 370 - 415 C.E. She is noted as the first women in mathematics, philosophy, and astronomy.

Q: What philosophical movement did she lead?

A: Hypatia led a philosophical movement called Neoplatonism which was developed from the ideas of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato.

Q: Where did she live?

A: Hypatia lived in Alexandria, Egypt during her time.

Q: What role did Theon play in her life?

A: Theon was Hypatia's father and he was also a mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher. He may have been the director of the Museum of Alexandria at one point which played a big role in education for both him and his daughter. He also worked with her on commentaries of Ptolemy's work together.

Q: Who is Synesius of Cyrene?

A: Synesius of Cyrene was one of Hypatia's students whose letters provided some important information about her life and teachings. She taught him about building an astrolabe.

Q: Why do people think she died?

A: People believe that radical monks murdered her because pagans seemed to have caused enmity among the mainly Christian town by persecuting her so they scattered her body parts around the city after killing her at 45 years old in 415 C.E..

Search within the encyclopedia