Anti-nuclear movement in Australia

The anti-nuclear movement in Australia has a long history of development. Nuclear weapons testing, Australia's uranium mining and export, and the numerous incidents involving the use of nuclear energy have often been the subject of public debate in Australia. The roots of this anti-nuclear movement lie in the controversy over French nuclear weapons testing in the Pacific from 1972 to 1973 and the debate from 1976 to 1977 over uranium mining in Australia.

Some environmental groups formed in the mid-1970s after nuclear incidents, such as the Movement Against Uranium Mining and Campaign Against Nuclear Energy (CANE), which cooperated with other environmental groups such as Friends of the Earth Australia and the Australian Conservation Foundation. A resurgence of this movement developed in 1983 when the newly elected Labor government did not stop uranium mining, contrary to its earlier promises. In the late 1980s, as the price of uranium fell and the cost of nuclear power rose, it appeared that the anti-nuclear movement had succeeded, and CANE disbanded itself in 1988.

When proponents of the use of nuclear energy stated that such use could play a part in solving the problem of global warming, the Australian government showed renewed interest in nuclear energy. Opponents and some Australian scientists pointed out that nuclear energy in Australia can in no way replace energy sources that are available in sufficient quantities and that uranium mining itself is a significant source of greenhouse gases.

To date (2011), Australia does not operate a nuclear power plant and has not built any nuclear weapons. The last failed attempt to build a nuclear power plant - the Jervis Bay nuclear power plant - took place in 1970.

![]()

The following parts of this section seem to be out of date since 2011: What does the current government say ?

Please help to research and insert the missing information.

Wikipedia:WikiProject Events/Past/2011

Julia Gillard's 2011 ruling Australian Labor Party (ALP) is opposed to building nuclear weapons and in favour of building a fourth uranium mine, which the ALP's 2009 National Conference decided to do.

Uranium is currently being mined in Australia, at the Olympic Dam, Beverley mines - both in northern South Australia, and at the Ranger uranium mine in the Northern Territory. In April 2009, development began at the Honeymoon Uranium Mine, another uranium mine located in South Australia.

Australia has operated a HITAR-type research reactor since 1958 and as of 2007 operates a research reactor, the Open Pool Australian Lightwater Reactor (OPAL) in Lucas Heights, a suburb of Sydney.

Nuclear weapons test sites in Australia

History

1950s and 1960s

In 1952 the Australian government opened the Rum Jungle uranium mine, located 85 km south of Darwin, the ancestral Aborigines were not consulted and the mine site developed into an ecological debacle. In 1952, the Liberal Party-led Conservative government of Robert Menzies passed the Defence (Special Undertakings) Act 1952, which allowed the government of the United Kingdom to conduct above-ground nuclear weapons tests in remote areas of Australia. The first nuclear weapons test in Australia took place on 15 October 1953 in the Woomera Prohibited Area. Further tests were conducted at Maralinga on the Emu Fields in South Australia between the years 1955 and 1963. The truth about the legal and political implications, as well as the environmental and Aboriginal consequences in the area of these test programs, only crystallized over time. The secrecy of the British nuclear testing program and the remoteness of the test sites meant that public awareness of the risks in Australia grew very slowly.

As the Ban the Bomb movement emerged in Western societies during the 1950s, Australian opposition to British nuclear weapons testing also grew. An opinion poll conducted in 1957 showed that 49% of the Australian public opposed these tests and only 39% were in favour. In 1964, peace marches with "Ban the Bomb" placards were held in several major Australian cities.

In 1969, the first Australian nuclear power plant with a capacity of 500 megawatts was planned: The Jervis Bay Nuclear Power Station, on the Jervis Bay Territory 200 km south of Sydney. A local opposition campaign formed and the South Coast Trades and Labour Council, which organises workers in the region, declared that it would refuse to participate in the reactor construction. Environmental studies and other preliminary work on the area had been completed, two bid openings had taken place, tender documents had been reviewed and initial foundation work had been completed, but in 1971 the Australian government decided not to pursue the project for a number of reasons, mainly economic.

1970s

The political controversy over France's 1972-1973 nuclear bomb tests in the Pacific mobilised some Australian groups and unions. In 1972, the International Court of Justice was seized by Australia and New Zealand over France's nuclear weapons tests on Mururoa Atoll. In 1974 and 1975 uranium mining in Australia came under political scrutiny and local Friends of the Earth Australia groups formed. The Australian Conservation Foundation also began to speak out again on uranium mining and supported grassroots activists. The environmental impact of uranium mining and the poor waste management of the first Rum Jungle uranium mine led to extensive environmental debate in the 1970s. The Australian anti-nuclear movement gained further momentum from statements on the nuclear option by various figures, such as nuclear scientists Richard Temple and Rob Robotham, and writers Dorothy Green and Judith Wright.

Due to a report by Russell Fox in 1976 and 1977, uranium mining became the focus of public political controversy. Some environmental groups formed as a result of incidents at nuclear power stations, such as the Movement Against Uranium Mining, which was formed in 1976 when the Campaign Against Nuclear Energy was held in South Australia in 1976. These groups also cooperated with other environmental groups such as Friends of the Earth Australia and the Australian Conservation Foundation.

In November and December 1976, 7,000 people marched through Australian cities protesting against uranium mining. In April 1977, the first national demonstration, coordinated by the Uranium Moratorium organisation, took to the streets with some 15,000 demonstrators in Melbourne, 5,000 in Sydney and others in other Australian cities. In a significant national signature gathering effort, over 250,000 signatures were collected in support of a 5-year moratorium. In August of that year, 50,000 people demonstrated across the country and opposition to uranium mining developed political strength.

When in 1977 the Australian Labor Party (ALP) favoured an indefinite moratorium on uranium mining at a national conference, the anti-nuclear movement decided to support the ALP in the coming election. However, there was a setback when another ALP conference voted for a "one mine policy" and when the ALP won the 1983 election, another ALP conference voted for a "three mines policy". This decision entailed the retention of the three then operating uranium mines, Nabarlek uranium mine, Ranger uranium mine and Olympic Dam. This also meant the continuation of the existing mining contracts, but the opening of new uranium mines was excluded.

1980s and 1990s

Between 1979 and 1984, Kakadu National Park, located at the Ranger uranium mine and one of the few Australian sites with UNESCO World Natural and Cultural Heritage status, was largely developed. The contradiction between natural and cultural interests and uranium mining led to long-lasting tensions in the area. These disputes led to a demonstration march in Sydney on Hiroshima Day 1980, supported by Movement Against Uranium Mining (MAUM), calling for "Keep uranium in the ground" and "No to nuclear war". Later that year, in an overarching action, the Sydney City Council officially declared this city a Nuclear Weapons Free Zone, and numerous other local assemblies in Australia joined the campaign.

In the 1980s, academics such as Jim Falk criticised the "deadly connection" between uranium mining, nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons, describing Australia's nuclear policy as linking "proliferation of weapons of mass destruction" to the "plutonium economy".

On Palm Sunday 1982, about 100,000 Australians took part in anti-nuclear demonstrations in the country's largest cities. These events grew steadily to 350,000 demonstrators by 1985. This movement targeted Australia's ongoing uranium production and export, called for the banning of nuclear weapons, the removal of foreign military bases on Australian soil, and a nuclear-free Pacific. Opinion polls showed that half of the Australian population opposed uranium mining and export, as well as opposing the presence of US nuclear-armed warships in Australia. According to public opinion polls, 72% of the population believed that nuclear weapons should be banned and 80% favoured the creation of a world without nuclear energy.

A Nuclear Disarmament Party won a seat in the Australian Senate in 1984, but soon disappeared from the political scene. The ALP-led governments of Bob Hawke and Paul Keating (1983-1996) were "uneasy standoff in the uranium debate". The ALP, while acknowledging community sentiment against uranium mining, was reticent to oppose the mining industry.

On Palm Sunday 1986, 250,000 people took part in anti-nuclear demonstrations in Australia. In Melbourne, the Seamen's Union of Australia boycotted work for foreign nuclear warships.

Australia's only nuclear engineering training school, the former School of Nuclear Engineering at the University of New South Wales, closed in 1986.

In the late 1980s the price of uranium fell and the cost of using nuclear power rose and it seemed that the anti-nuclear movement was successful and eventually the anti-nuclear movement in Australia dissolved itself, two years after the Chernobyl disaster.

Government policy was against the opening of new uranium mines until the 1990s, although there were occasional public discussions about this. After a protest march in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, the opening of a new uranium mine at Jabiluka was prevented in 1998.

In 1998 there was a plan by Pangea Resources, an international consortium, to dump nuclear waste in Western Australia. This plan was to store 20% of the world's waste, nuclear fuel and nuclear weapons material. This concept was "publicly condemned and abandoned".

2000s

In 2000, the Ranger uranium mine in the Northern Territory and the Olympic Dam mine in South Australia were operating and the Nabarlek uranium mine had closed. A third uranium mine, the Beverley was in operation. Various advanced plans for uranium mining such as the Honeymoon uranium mine in South Australia, the Jabiluk uranium mine in the Northern Territory and Yeeliree uranium mine in Western Australia had been halted because of political and Aboriginal opposition.

In May 2000, an anti-nuclear demonstration was held at the Beverley uranium mine by 100 protesters. Ten of the protesters were abused by police and later sued by the South Australian government for AUD $700,000 in damages.

According to the McClelland Royal Commission report, a complete decontamination had to be carried out at Marlalinga in the outback of South Australia because of the British atomic bomb tests in the 1950s, which cost more than AUD $ 100 million. There was only controversy over the methods and success of this.

The price of uranium began to rise in 2003, and when proponents of nuclear energy began to express interest in the face of global warming, the Australian government showed interest. However, in June 2005, the Australian Senate passed a motion against the use of nuclear energy. Subsequently, the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Industry and Resources issued a report in favour of the use of nuclear energy in Australia, which took a positive stance. Towards the end of 2006 and the beginning of 2007, statements by Prime Minister John Howard were reported in which he favored nuclear power on environmental grounds.

In the face of advocacy for the use of nuclear power as a possible alternative to climate change, opponents of nuclear power and scientists countered that nuclear power cannot be decisively replaced by other energies in Australia and that uranium mining itself results in significant greenhouse gas emissions. The anti-nuclear campaigns publicly spread concerns about possible reactor sites: these fears benefited the anti-nuclear parties and this led to success in the 2007 national election. Kevin Rudd's Labor government was elected in November 2007 and decided against the use of nuclear power. The anti-nuclear movement began to become active again in Australia, expanding its opposition to the existing uranium mines, working against the development of nuclear power and criticising the advocates of nuclear waste storage.

In October 2009, the Australian government continued to pursue plans to store nuclear waste in the Northern Territory. However, there was opposition from the indigenous people there, the Northern Territory government and most of the people of that state. In November 2009, 100 protesters from the anti-nuclear movement gathered outside Parliament House with a sit-in in Alice Springs, demanding that the Northern Territory government not approve the opening of a mine at the nearby uranium deposit.

In early April 2010, more than 200 environmentalists and Aboriginal people gathered in Tennant Creek to protest the nuclear waste repository being built at Muckaty Station in the Northern Territory.

Western Australia has a significant Australian uranium deposit that was under a government ban for exploitation between 2002 and 2008. This ban was relaxed by the Liberal Party when it was in power and numerous companies explored these deposits. One of the world's largest mining companies, BHP Billiton, plans to develop the uranium deposit at Yeelirrie in 2011 in a $17 billion project.

Towards the end of 2010, there were Australian debates about whether the nation should use nuclear power as part of an energy mix. Nuclear power appears to be "a divisive issue that can arouse deep passions among those for and against",

Decision against the repository at Muckaty Station

In June 2014, the Australian government declared that it would not proceed with the plan for a repository at Muckaty Station. This was preceded by a lawsuit against the agreement concluded in 2007 between the government and the Ngapa clan for the construction of a repository for nuclear waste from Sydney's medical and research reactors. Among others, the Northern Land Council had sued against it.

Australia's oldest uranium mine, Radium Hill, 1954.

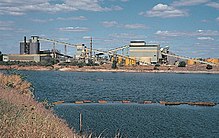

Ranger uranium mine at Kakadu National Park

Aerial view of the Ranger 3 mine, located in the Kakadu National Park area.

Nuclear incidents

Because of the environmental, political, economic, social and cultural problems, the shortcomings of nuclear power as an energy source and the lack of a sustainable energy policy, nuclear power and uranium mining are rejected in Australia. However, the most weighty reason for rejection is seen to be proliferation of nuclear weapons of mass destruction. For example, the Ranger report stated that: "The nuclear power industry is unintentionally contributing to an increased risk of nuclear war. This is the most serious hazard associated with the industry". (German: The nuclear industry is unintentionally contributing to an increased risk of nuclear war. This is the most serious hazard associated with the industry).

The health risks associated with the use of nuclear energy and nuclear materials play an important role in Australian anti-nuclear campaigns. This was evident in the case of the Chernobyl disaster, but for Australians the controversy over nuclear bomb testing in Australia and the Pacific plays a special role as a local factor, due to a well-known opponent of nuclear use, Helen Caldicott, a medical professional.

The economic use of nuclear energy is questionable because this use is uneconomic for Australia, especially since coal is abundant in Australia.

The nuclear industry in Australia has produced a total of 3,700 m³ of nuclear waste over the past 25 years, which is stored in more than 100 locations and 45 m³ is added each year. There is no sustainable strategy for nuclear waste storage in Australia.

From the perspective of the anti-nuclear movement, today's problems with nuclear power are mostly the same problems as in the 1970s. This movement argues that nuclear power plants carry the risk of incidents and that there is no solution for the long-term storage of nuclear waste. The proliferation of weapons of mass destruction continues, which can be seen after the construction of nuclear power plants and the acquired expertise in operating nuclear facilities in Pakistan and North Korea. The alternatives to nuclear power are efficient energy use and renewable energy, especially wind power, which promotes the development of a renewable energy industry.

Questions and Answers

Q: Does Australia have any nuclear power stations?

A: No, Australia does not have any nuclear power stations.

Q: What is the stance of the Rudd Labor government on nuclear power for Australia?

A: The Rudd Labor government was opposed to nuclear power for Australia.

Q: Does Australia have any research reactor related to nuclear power?

A: Yes, Australia has a small research reactor (OPAL) in Sydney.

Q: Does Australia export uranium?

A: Yes, Australia does export uranium.

Q: Have nuclear issues and uranium mining often been discussed publicly in Australia?

A: Yes, nuclear issues and uranium mining have often been the subject of public debate in Australia.

Q: When did the anti-nuclear movement in Australia begin?

A: The anti-nuclear movement in Australia began with the 1972-73 debate over French nuclear testing in the Pacific and the 1976-77 debate about uranium mining in Australia.

Q: How many groups were involved in the 1972-73 debate over French nuclear testing in the Pacific?

A: The text does not indicate how many groups were involved in the 1972-73 debate over French nuclear testing in the Pacific.

Search within the encyclopedia