Hunter-gatherer

![]()

This article is about the game hunters - for the YouTube channel, see Hunters & Gatherers.

In anthropology and ethnology, hunter-gatherers or game and field exploiters are local communities and indigenous peoples who obtain their food largely by hunting wild animals, fishing, and gathering wild plants or small animals. Some authors consider the terms wild hunter as a pejorative term (suggests "exploitation") to be dispensed with. In fact, this way of life requires a high degree of flexibility, adaptability and special knowledge.

A distinction is often made between unspecialized (also simple) and specialized (also complex or differentiated) hunter-gatherer cultures. The former use a very broad but varying food supply in very large tails, where they seasonally nomadize in small hordes. The latter primarily use one or more specific, locally abundant species that allow for larger groups and longer periods of sedentariness.

The subsistence form of hunting, fishing and gathering - an appropriative or "extractive" way of life through which the reproduction of natural resources is not deliberately and consciously influenced - is the oldest traditional economic form of humankind. This is not to say that hunter-gatherers have not had a relevant influence on the ecological system of their habitat over long periods of time.

The classification of the individual economic modes is not uniform in the literature: for example, Lomax and Arensberg distinguish "hunters and fishermen" from "gatherers" and Hans-Peter Müller separates "fishermen" from "hunters and gatherers" if they live predominantly from fish. The German agronomist Bernd Andreae wrote in 1977:

"At the beginning of development, according to all cultural-historical theories of development, there is a pure occupation economy, which is almost always coupled with a nomadic or semi-nomadic way of life. Depending on the food sources offered by nature, it is a gathering economy, as in all three of Eduard Hahn's developmental trajectories, or hunting and fishing, as in Richard Krzymowski's three-stage theory, or else combination forms."

The way of life of many hunter-gatherer societies can only be reconstructed today from archaeological finds. The written reports of early expeditions are not always reliable. Thus, in many concrete cases, it is difficult or even debatable to answer the question whether the way of life of extinct as well as existing wild hunter cultures is an autonomous and original one, or a specialized way of life adopted through cultural contacts or created through advantageous exchange, or even a secondary phenomenon of the post-Neolithic period created by isolation and displacement of peoples in deserts and semi-deserts.

In any case, it is assumed that in many regions (e.g. Central Africa, South America, India) there were lively exchange relationships between wild hunters and planters for thousands of years (e.g. game or assistance in exchange for agricultural products), so that an isolated consideration of the extractive way of life can be misleading.

It is very difficult to determine how many people worldwide live from hunting and gathering activities today, as additional forms of subsistence and gainful employment are currently used in many cases. The number of people whose livelihoods are largely based on extractive activities is at most 3.8 million.

However, local groups of hunter-gatherers are also found in areas where other forms of food acquisition are not possible at all. Around 1500 AD, about half of the inhabitable land area of the earth was still populated by hunter-gatherers. At the same time, however, their share of the world's population was only an estimated 1 percent - at present it is less than 0.001 percent: an estimated 50,000 to 60,000 people, with a downward trend.

Members of the Hadza in African Tanzania, one of the last peoples to live as traditional hunter-gatherers (2007)

.jpg)

For many Nordic indigenous people, hunting is an important additional source of self-sufficiency (Greenland Inuit, 2007)

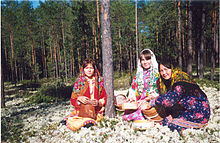

Self-sufficiency is also achieved by gathering, traditionally carried out by women (Khanty in Western Siberia, 2013).

Land use and nutrition

The economic form of unspecialized hunting and gathering usually requires (depending on the respective food supply of the inhabited climatic zone) sufficiently large tail areas, which can only be used extensively due to their extent. In the occupation economy common among hunter-gatherers, a person needs an area of about 20 square kilometers in which to roam in search of food. In the process, the vegetation and the naturally occurring species composition are not deliberately changed.

In terms of area, this subsistence system uses by far the least energy. Unless modern technologies (weapons, tools, vehicles) are used, it is exclusively a matter of metabolised energy in the form of muscle power. Although this leads to a low yield without surpluses, which is clearly below that of all agricultural systems, the energy efficiency in contrast is very high and surpasses all engineered economic systems many times over: the energy yield is about six times the input and the impact on the natural balance is extremely low (HANPP <0.1 %). In terms of adequate food supply, these constellations allow only very low population densities: For southern and eastern Africa, for example, 0.8 to 2 inhabitants/km² are given as a maximum.

The composition of the food is very different in unspecialized groups and also varies greatly in the course of the year. The more inhospitable the habitat, the larger the "managed" area must be, the longer the distances and the smaller the number of people in the hordes.

Some studies of recent peoples of the subtropics and tropics have found that 60 to 70, and in individual cases up to 80 percent, of their food is gathered (mainly vegetable). Thus, South and Southeast Asian jungle peoples feed almost entirely on the gathering economy. Some Indian ethnic groups (such as the Malapantaram and Aranandan of Kerala) do not even have bows or spears. The emphasis in the warm countries is often on vegetable food even where game and fish are abundant. It is likely that the uncertain quotas of prey, the risks of hunting and the easy availability of gathering food are major factors in this decision. There are exceptions, however, such as the Huaorani in the Amazon lowlands of Ecuador, who feed primarily on meat. For other ethnic groups - especially in the far north - an average of 65 percent animal food has been determined, in extreme tundra regions up to 90 percent. Here, plant food is only available from May to September at the most.

The findings of paleoanthropology on the diet of Stone Age people provide evidence of a predominantly plant-based diet; animal food did not play a decisive role and was often limited to insects as a source of fat and small game as a source of animal protein.

In the case of specialized game or field hunters who subsisted primarily by hunting certain common large animal species (bison, caribou, marine mammals, small game), by fishing in permanently fish-rich waters, or by harvesting masses of wild fruits (wild rice, black oak, sweet grasses, sago palm), different standards must be applied to both land use and diet. They were semi-nomadic, semi-sedentary, or sedentary when resource density was high (such as game ranges, densely stocked grasslands, riparian zones of large bodies of water), lived in larger, more socially complex groups, and used resources more intensively.

Such complex societies already existed 20,000 years ago (for example in the Dordogne, Ukraine, Japan, Denmark, the Levant). The finds there suggest higher population densities, division of labour and specialisation, barter and long-distance transport, as well as greater social stratification.

The Mongongo nut, nutritious and abundant in the territory of the San

The Anishinabe of southern Canada specialize primarily in water rice

Traditional hunters like the Hadza often have to migrate very far in search of food. Nevertheless, the supply is usually safe and balanced.

Collective food makes up the main part of the diet in the warm regions

Hunt

Hunting methods

Hounding as an endurance hunt

The oldest hunting method of man is probably the hunt in the form of persistence hunting. This is based on the superior running endurance of humans compared to almost all mammals. Humans, who are sufficiently well equipped for longer, faster runs, can cool down effectively due to their approximately two million sweat glands as well as their weak body hair, and can therefore keep up a longer run for hours. The Khoisan hunters of southern Africa still kill fast hoofed animals such as zebras or steenboks without any weapons at all, running after them until they collapse, exhausted. Some American Indian tribes also hunted pronghorns as endurance hunters. Some Aborigines in Australia hunted kangaroos in this traditional way.

According to a model calculation published in 2020, endurance hunts can be sustained for up to 5 1⁄2 hours under the climatic conditions of the Kalahari without the need or necessity for the native hunters there (anatomically modern humans and Homo erectus) to carry water.

This method of hunting differs from that of most predators. For example, cheetahs, which can reach speeds of over 100 kilometres per hour for short periods of time, can only sustain this speed for a few minutes and must reach their prey in one run or it will escape. Other predators also can only sustain high speeds for a short time or use other tactics such as being encircled by a pack.

Driven Hunt

When Cabeza de Vaca was the first white man to come into contact with many of the Indian tribes of North America, beginning in 1528, he witnessed drive hunts, including drive hunts with all-round fire. He described hunting with fire thus, "They also kill deer by enclosing them with fires; and this method they also use to deprive the animals of food, so that necessity compels them to seek it where the Indians want it.... In this way they satisfy their hunger two or three times a year...". Another very old method of hunting may be "cliff-driving," in which the game was panicked and driven over the edge of a cliff.

Trapping

Trapping has been documented for the Aborigines of Australia, among others.

Hunting weapons

Very old is the hunting with throwing sticks especially on birds and smaller animals and with spears on bigger game.

Litterbug

→ Main article: Limb

In addition to humans, monkeys have also been observed to throw sticks or hard fruit from trees at approaching predators. Therefore, the use of throwing woods is thought to be older than that of the spear, a stick sharpened at least at one end, which flies straight and penetrates the game or the opponent. The wood spinning in flight could, for example, stun a bird by the force delivered on impact (hit zone head), or prevent it from flying away by temporarily paralyzing or breaking bones when hit on the wings. Mature constructions in the hands of a skilled hunter also kill other and larger prey.

The first item found during the excavation in Schöningen (see below) was a presumed throwing stick: a stick sharpened at both ends and about 50 centimetres long. Impressive and, for example, also proven in ancient Europe are the throwing sticks that the Australian Aborigines used for hunting (boomerangs). They could weigh up to 2 kilograms and be 1.30 metres long. Skilled throwers could throw such a boomerang up to 100 metres. These hunting boomerangs do not return to the thrower, but are optimized for a straight and stable flight. They were also used as digging sticks to dig up roots. Throwing sticks with an age of 20,000 years have been found in the European Carpathians. Also preserved are depictions from Ancient Egypt showing bird hunting with throwing sticks.

Spears

Spears were already used by early representatives of the genus Homo such as Homo erectus (Homo heidelbergensis).

The oldest hunting weapons found so far are the Schöningen spears, which are about 300,000 years old. During lignite mining in Schöningen, Lower Saxony, 7 spears made of spruce wood were found amidst 18 wild horse skeletons. These spears had a length of between 1.82 and 2.50 metres and were made of the harder base wood, their centre of gravity was at the tip. The throwing characteristics of replica spears resemble those of modern women's competition spears, with a hunting range of about 15 meters. At that time, Europe was inhabited by Homo heidelbergensis, which later gave rise to Neanderthal man; modern man (Homo sapiens) spread to Europe no earlier than 45,000 years ago.

Thousands of bones were found in the area of the early Stone Age hunting camp of Bilzingsleben, 60 percent of which were bones of large animals, including wild cattle, wild horses, bears, rhinoceroses and elephant calves.

Lance and harpoon

The Neanderthals who emerged from the European occurrence of Homo erectus also hunted with lances, i.e. sharpened wooden sticks as thrusting weapons, which, however, could also be equipped with a leaf-shaped stone blade. In the German Lehringen, for example, a yew wood lance 2.38 metres long was found in the ribcage of a forest elephant skeleton. Neanderthal skeletons in many cases show traces of bone fractures in the arms and head. Among all historical and modern human groups, archaeologists found a similar frequency of bone fractures only among modern rodeo riders - whose cause of bone fractures is not mainly due to falls, but comes from the hooves of the animals. Neanderthals were also exposed to this danger when hunting big game at close range.

The lance was used as a hunting weapon until modern times, especially for hunting wild boar (compare Saufeder).

As a thrust-weapon mostly with barbs to the hunt on fish, the people developed the harpoon.

Spearthrower

A doubling of the range of spears was achieved by humans through the development of the spear slinger. The spear sling was developed in Europe during the last ice age. It is a hunting weapon consisting of the projectile and the throwing device. The oldest find can be assigned to the late Solutrean (about 24,000 to 20,000 years ago). However, the predominant part from stratigraphically secured contexts comes from the Magdalénien IV (about 15,400-14,000 years ago). The main focus of their distribution is southwest France, some finds come from Switzerland, Germany and Spain. Worldwide, the spear sling is archaeologically and ethnographically documented in Micronesia, Australia, New Guinea, and among the Eskimo. In Central America the spearthrower was used as a weapon of war.

bow and arrow

At even greater distances and up to the tops of trees and flying birds, the bow extended the hunting range of the people. Some tribes learned to poison the arrowheads, so that they could also kill large animals with small arrows, for which spears were previously needed.

Nets and snares

As people began to process fiber, they also began to hunt animals with snares, as well as catch birds and fish with nets.

Blowpipe

A few tribes of hunter-gatherers also used blowguns, with which they shot mostly poisoned arrows. For example, Indian tribes in the rainforests of South America hunt primates in the highest treetops with blowpipes about three meters long and curare or poison dart frog-poisoned arrows.

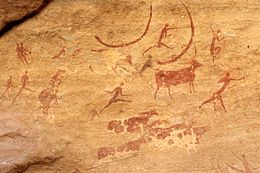

Hunters with bows and cattle as prey (rock paintings in the Sahara)

Harpoon forms from the Stone Age, here the Magdalenian (18,000-12,000 BC): 1 Mas d'Azil 2 Bruniquel 3, 4, 5 La Madeleine 6, 7 Lortet

Throwing woods from Aborigines in Australia

Search within the encyclopedia