Human rights

This is the sighted version that was marked on June 2, 2021. There are 3 pending changes that still need to be sighted.

Human rights are morally based, individual rights of freedom and autonomy to which every human being is equally entitled simply by virtue of being human. They are universal (apply to all people everywhere), inalienable (cannot be ceded) and indivisible (can only be realized in their entirety). They include civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights. Human rights are often derived from natural rights and the inviolable human dignity.

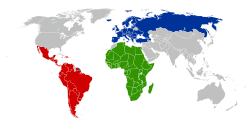

Today, almost all countries in the world have ratified international human rights treaties or explicitly mentioned human rights in their constitutions, thus committing themselves to formulating them as enforceable rights in their respective national laws. At the international level, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, which has a universal and global claim but is not formally binding. In 1966, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR, "UN Civil Covenant") and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR, "UN Social Covenant") were subsequently adopted, both of which are legally binding. Human rights treaties have also been adopted at the intergovernmental level, differing in their binding powers and human rights concepts: The European Convention on Human Rights of 1953, the American Convention on Human Rights of 1969, the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights of 1981, the Arab Charter on Human Rights of 1994, and the Asian Declaration on Human Rights of 2012. In addition, there are other regional treaties and agreements that advocate for the observance of human rights. Supranational courts, such as the European or Inter-American Court of Human Rights, sanction human rights violations by their member states. In addition, international criminal tribunals such as the International Criminal Court punish particularly serious crimes against humanity, genocides, war crimes or wars of aggression.

Nevertheless, serious and in some cases systematic human rights violations still occur in many states today. These are documented and denounced by a large number of institutions. At the level of the United Nations, the High Commissioner for Human Rights is responsible for this, publishing an annual Human Rights Report. In addition, a large number of private human rights organizations, such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, monitor the implementation of and respect for human rights.

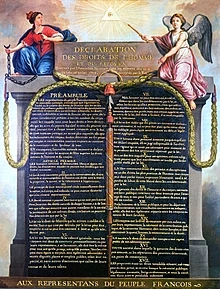

The concept of human rights is not a purely "Western" or modern phenomenon, but can be traced back to all epochs and regions of the world and often represents a core of religious and cultural values, even if their interpretation varied historically in some cases. The first examples of such documented rights can be found as early as 2100 B.C. with the Codex Ur-Nammu from Mesopotamia, which, among other things, provided for a right to life, or in 538 B.C. with the Cyros Cylinder from Persia. The most famous national human rights documents since the Age of Enlightenment are the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and the U.S. Bill of Rights.

In contrast to human rights, to which every person worldwide is entitled, "fundamental rights" are limited to the jurisdiction of the state that expressly guarantees these rights by constitution. "Civil rights," in turn, are called the part of fundamental rights that are reserved only for the citizens of the country in question.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 1, on the outside wall of the Austrian Parliament building in Vienna.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, 1789

The English Bill of Rights (1689) overcame the idea of divine right that had prevailed until then and replaced it with the principle of parliamentary sovereignty. This paved the way for the political implementation of human rights.

United States Declaration of Independence, 1776

The Cyros Cylinder from Persia (538 B.C.), which is commonly regarded as the "first charter of human rights

Essence of human rights

Universality

Universality in human rights stands for universality. This means that human rights are valid everywhere and for all people at all times. As a natural right, they stand above all positive law and are thus independent of and in their essence inviolable by state legislation.

In order for this first subjective meaning to be practically realizable, the second intersubjective meaning must be fulfilled: The recognition of the human right and its practical validity for every human being. Accordingly, every human being is obliged to respect the human rights of his fellow human beings. Therefore, viable and legal instruments are needed to guarantee the universal recognition of human rights. It is therefore only possible to speak of a human rights guarantee if the claims are actually accepted and enforceable as legal norms. Therefore, all states that have joined the UN have been obliged to give full effect to human rights in their national legal systems.

However, universality in particular is not always guaranteed in practice, as the formulation and protection of specific human rights depend on political views and the associated legal enforcement within states and institutions. Constraints on who is considered a human being (legal subject), against whom these rights can be asserted (legal addressee), how the content of human rights is determined and who enforces them (sanctioning authority) are therefore conditioned by varying historical, cultural or even political factors in each case. Cultural relativism opposes the universal claim that human rights are universally valid.

Egalitarianism

Human rights are egalitarian, i.e. they apply equally to every human being; regardless of, for example, origin, gender, nationality, age, skin color, etc. This principle of equality is summarized in Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights with:

"All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights."

Accordingly, every person is equal before the law and may not be discriminated against.

The discussion about equal rights for men and women also revolves around this important fundamental norm. However, social or societal equality is often confused with the prohibition of differentiation in human rights. Equality in all areas of life, including private ones, is not the content of the regulation, however. Equality of opportunity, in turn, is an actual legal reflex of the regulation, as far as it goes.

Inalienability

Human rights cannot be taken away from anyone, nor can they be willingly given up or ceded. This also applies if a restriction of human rights is attempted to be justified with an "even higher good" (of whatever kind); for example, in the sense of the "common good" or simply because a majority of the population has so decided. They are thus in contradiction to collectivism. Since human rights are individual (highly personal) rights, they cannot be subordinated to any collective and thus escape state sovereignty. Therefore, the use of torture, for example, would remain unlawful even if it were based on a formally lawful law or even on a referendum.

This concept is realized in Germany, for example, with the eternity clause in the Basic Law. In concrete terms, this was a lesson learned from the National Socialist era, in which individual human rights violations were justified on the grounds that they served a "higher purpose" in the sense of the "national community" and were democratically legitimized. This collectivist view was also summed up by the formula "You are nothing, your people are everything!" Such semantics can also be found in most other totalitarian dictatorships.

Indivisibility

In addition to the principle of the universality of human rights, the claim of their indivisibility is also raised. Human rights must therefore always be realized in their entirety. It is not possible to implement rights to freedom if the right to food, for example, is not realized at the same time. Conversely, the violation of economic or cultural rights, such as forced displacement, the banning of languages or the deprivation of livelihoods, is usually accompanied by the violation of civil and political rights.

Normative content

Legal sources

The internationally authoritative source for the existence and content of human rights is the International Bill of Human Rights of the United Nations. In addition to the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which is, however, only a declaration adopted by the UN General Assembly and not directly binding on member states, the central human rights instruments within this corpus are:

- the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and

- the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Both covenants were adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1966 and entered into force ten years later after being ratified by the required number of member states. They are binding law for all member states that have ratified them (see also the section on "United Nations" below).

In addition, there are a large number of conventions that regulate the protection of individual human rights in detail, for example

- the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

- the Geneva Refugee Convention

- the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

- the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women

- the UN Convention against Torture

- the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

- the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families

- the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

- the Optional Protocol on the Right of Individual Complaints to the UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

- the Optional Protocol on the Abolition of the Death Penalty to the UN Civil Covenant

- the Optional Protocol on the Right of Individual Complaints to the UN Social Covenant

In addition, there are regional human rights conventions on the various continents. In Europe, this is the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) or Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. It contains a catalog of fundamental rights and human rights. The convention was negotiated within the framework of the Council of Europe, signed in Rome on November 4, 1950, and entered into force on July 3, 1953. Africa (Banjul Charter) and the American double continent (Inter-American Convention on Human Rights) also each have their own regional human rights conventions.

See also: Human rights treaties

Civil and political rights

Personal rights (basic rights)

→ Main article: Personal rights

- Right to life

- Right to physical integrity

- Prohibition of torture

- Protection against human experimentation without the patient's consent, against forced sterilization and castration, protection against corporal punishment and corporal beating, and protection against degrading or humiliating treatment (such as honor penalties), abolition of corporal punishment in education and schools

Freedom rights

→ Main article: Freedoms

- Right to liberty, property and security of person

- General freedom of action that can only be restricted by law

- Freedom from arbitrary interference with privacy (inviolability of the home, secrecy of correspondence, etc.)

- Freedom of expression

- Freedom of thought, conscience and religion

- Freedom of travel

- Freedom of assembly

- Freedom of Information

- Freedom of occupation

Judicial human rights

- Effective judicial legal protection in the event of legal infringements

- Right to a fair trial before an independent and impartial tribunal of lawful judges

- Right to be heard (audiatur et altera pars)

- No punishment without prior law (nulla poena sine lege)

- Presumption of innocence (in dubio pro reo)

Economic, cultural and social rights

In addition, the legal standards set forth in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights include:

- Right to self-determination (Art. 1)

- Equal rights for men and women (Art. 3)

- Right to work and adequate remuneration (Art. 6/7)

- Right to form trade unions (Art. 8)

- The right to social security (Art. 9)

- Protection of families, pregnant women, mothers and children (Art. 10)

- Right to an adequate standard of living, including adequate food clothing and housing (Art. 11)

- Right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health (Art. 12)

- Right to education (Art. 13)

- Right to participate in cultural life (Art. 15)

The economic, social and cultural rights from the UN Social Covenant are also referred to as "social human rights" for short. Whereas civil and political rights are now included in numerous constitutions and their violation is actionable in court, social human rights are not positively standardized in law in all member states.

Against the existence of economic, cultural and social rights, it is sometimes argued that here the traditional right of defense (status negativus) turns into a status positivus (entitlement to the granting of positive social benefits).

The characterization of civil and political rights as purely defensive rights, however, is just as erroneous as that of economic, social and cultural rights as purely guaranteeing rights. For example, guaranteeing internal and external security and an independently functioning judiciary is a positive state service. However, this is overwhelmingly seen as an actual purpose of the state and thus justified. The same applies to the enforcement of general and free elections.

At the same time, social human rights often appear as defensive rights. These include refraining from forced displacement in the course of an internal conflict as well as respecting the right of an indigenous people to retain its language, legal system or institutions.

Therefore, the so-called Limburg Principles, which were drafted in 1986 by a group of United Nations human rights experts, provide three types of obligations for each human right that the state must fulfill:

- Duty to respect: The state is obliged to refrain from violating rights;

- Duty to protect: The state must protect rights from encroachment by third parties;

- Duty to guarantee: The state must ensure the full realization of human rights where this is not yet the case.

The understanding of human rights as purely defensive rights covers only the first of these three obligations. Within the United Nations human rights system, however, the more comprehensive understanding of human rights that emerges from the Limburg Principles can now be considered recognized.

In general, it should be noted that the European tradition often understands civil and political rights as the only "real" rights, whereas in countries where hunger or displacement or access to water are burning issues, economic, social and cultural rights receive more attention. The European Convention on Human Rights, for example, completely hides this area, while it plays a central role in the Organization of African Unity's Human Rights Charter. "This addresses the fundamental problem of whether individual liberty rights are effectively usable only on the basis of a collective minimum standard."

European Convention on Human Rights American Convention on Human Rights African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights

Questions and Answers

Q: What are human rights?

A: Human rights are the rights and freedoms that all people should have. They include things like freedom of speech, the right to a fair trial, and the right to be treated equally regardless of race, religion, ethnicity, nationality, age, sex, political beliefs (or any other kind of beliefs), intelligence, disability, sexual orientation or gender identity.

Q: Where do human rights come from?

A: Human rights are protected as legal rights in national and international law. The ideas of human rights were first outlined in Article 1 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

Q: Are human rights universal?

A: Yes. Human rights are meant for everyone - they must be treated globally in a fair and equal manner on the same footing with the same emphasis.

Q: Is it possible to only grant some human rights?

A: No. Every person has all these human rights - they cannot be divided up or granted selectively.

Q: How can we ensure that everyone is aware of their human rights?

A: It is important to educate people about their basic human right so that they know what they are entitled to and how to protect them if necessary. This can be done through campaigns by governments or NGOs as well as through media outlets such as television and radio programmes or online articles and videos.

Q: What does it mean for human rights to be indivisible?

A: Indivisibility means that all human rights must be respected together - no one should have more or less than another person when it comes to their basic entitlements under international law. All humans have an equal right to these protections regardless of who they are or where they come from.

Search within the encyclopedia