Huguenots

![]()

This article is about the French Protestants. For the opera by Giacomo Meyerbeer that premiered in 1836, see The Huguenots.

Huguenots is the term in use since about 1560 for French Protestants in pre-Revolutionary France. Their faith was Calvinism, the doctrine of John Calvin dating from the 1530s. Since the Edict of Nantes in 1598, the Huguenots were officially called religionists (religionnaires), and their denomination was referred to in state documents as the so-called reformed religion (Religion prétendue réformée, R.P.R. ). According to Patrick Cabanel, in 1560 the Huguenots represented about 2 million people, or 12.5% of the total French population at that time; other authors, such as Hillerbrand, assume 10% around 1572, also 2 million people.

In the 1520s, early Protestantism was tolerated only in the circle of intellectuals around Margaret of Angoulême (Cénacle de Meaux, "Circle of Meaux"). In general, the powerful Catholic clergy immediately introduced strong persecution. The first execution is dated 1523. Beginning with the Plakata Affair in 1534, the practice of the Protestant faith was suppressed by Francis I. The Protestant French were forced underground, and the first wave of flight occurred. Despite repressive measures, the Reformation was able to develop secretly.

This was followed by warlike conflicts in the second half of the 16th century, known as the Huguenot Wars (1562-1598). On the other hand, some representatives on the Protestant side also engaged in violence and rioting. For example, Catholic churches and monasteries were destroyed or looted by angry supporters of Calvinism, including the cathedral of Soissons in 1567 and the monastery of Cîteaux in 1589. There were also massacres against Catholics, such as the Michelade of Nîmes.

In 1589, the Huguenot Henry of Navarre ascended the throne of France. Until his abjuration in 1593, the Estates General acted in opposition to the king because of the opposition of a large part of the nobility. By provision of the Parlement of Paris, the loi salique was equated with the requirement of a Roman Catholic king. As a result, many refused to recognize Henry as king. The last supporter of the Catholic League, the Duke of Mercœur recognized Henry IV after a bribe of 4,300,000 livres.

After the Edict of Nantes in 1598, there was peace for about twenty years. During this time, France was able to regain its supremacy in Europe and rise to colonial power.

In 1621, as a result of the developing French absolutism, Huguenot uprisings broke out, ending with the Edict of Grace of Alès in 1629. Louis XIII withdrew the political and military rights considered as independence of the Huguenots within France (Etat dans l'Etat), but religious freedom remained guaranteed. Also in 1652, Louis XIV confirmed the clause of the Edict of Nantes that guaranteed the religious freedom of Reformed Protestants in France.

In 1661, strong persecutions began, which reached a climax under Louis XIV through the Edict of Fontainebleau from 1685, triggering a wave of flight of about a quarter of a million Huguenots to the Protestant areas of Europe and overseas. As a result, almost the entire Kingdom of France was cleared of Huguenots. The only exception was the Cévennes in eastern-northern Languedoc, which became the site of the Cévennes War. Persecution in France ended in 1787 with the Edict of Versailles. After the end of the persecution and the entry into force of the French Constitution of 1791, the term Protestants became more widely accepted; the term "Huguenots," on the other hand, usually refers to Calvinist believers at the time of their persecution in France.

All French Protestants form a minority of about 3% in predominantly Catholic France today. In 2012, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of France and the Reformed Church of France merged to form the United Protestant Church of France. The United Protestant Church of France comprises 250,000 Reformed Protestants, or about 0.4% of the total French population.

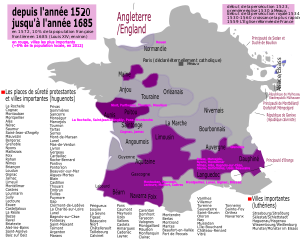

Cities with Reformed populations within France around the year 1685 (note: Spanish-language map). The city of La Rochelle was the leading Huguenot stronghold in France until the defeat of 1629. After that, all places de sûreté without exception had to demolish their fortifications. .

Huguenot cross, worn as jewelry by many French Calvinists

Etymology

The word Huguenot possibly goes back to the early New High German (Alemannic) term Eidgenosse and thus shows connections to Geneva. It first appears in French at the beginning of the 16th century in the form eygenot as a designation for the supporters of a political party in the canton of Geneva, who fought against the annexation attempts of the Duke of Savoy and therefore formed a confederation between Geneva and the confederate towns of Fribourg and Bern in 1526. These Eygenots or Eugenots were Catholics at the beginning, because Geneva was reformed only in 1536. In the second half of the 16th century, increasingly and in distinction to the Catholic Savoy, the term was used in the sense of "Protestant, Reformed", including by the Prince of Condé in 1562 in the form aignos. The Geneva freedom fighter Besançon Hugues as godfather in the naming is also considered.

Another assumption sees the origin of the word in the designation "Huis Genooten" (housemates) for Flemish Protestants who studied the Bible in secret. The origin of the word cannot be determined with certainty, but it is undisputed that the name did not originate as a proper name for the believers, but as a derisive term that was also intended to discredit them.

Finally, against this background, the following conceptual derivation is offered: In some regions of France in the 16th century, Protestants could meet only in secret, for reasons of persecution. They therefore moved at night to their meeting places, which were often located outside the towns. This is where Dante's Divine Comedy, which was very famous in France at the time, comes in. In it, Dante encounters the French king Hugues (Hugo) Capet wandering around in purgatory. In a speech, the king refers to himself as "the root of the evil tree" that has overshadowed Christianity. In analogy to this, the "wandering" Protestants are called little Hugos, "Huguenots".

Overview

Essentially, a western and a southern part (Le Midi/Occitania) of France became the main area of the Reformation.

Among Huguenot strongholds were the historic provinces of Aunis (with La Rochelle as its capital), Saintonge, Poitou, Limousin, Béarn (including Navarre), Foix, Languedoc and Dauphiné (southernmost parts of both of these provinces remained Roman Catholic). About equally divided were Aquitaine (including Labourd, more Huguenot Gascony and more Roman Catholic Guyenne), Angoumois and Auvergne. Only to a small extent Huguenot-influenced were Anjou (mostly Saumurois), Orléanais, La Marche, Bourbonnais, Nivernais, Touraine, Maine, and Côtes-d'Armor (part of Brittany).

In 1704, only a northeastern part of Languedoc (mainly Gard, Vivarais and Ardèche) located in the mountains (Cevennes) and a part of Dauphiné (Drôme) adjacent to these areas remained with the Reformed faith.

| Year | Number of Huguenots in France |

| 1519 | None |

| 1560 | 1.800.000 |

| 1572 | 2.000.000 |

| 1610 | 1.200.000 |

| 1629 | 1.000.000 |

| 1661 | 900.000 |

| 1685 | 800.000 |

| 1700 | less than 200,000 |

The persecution is abolished by the Edict of Versailles in 1787.

| Year | Number of Reformed Protestants in France |

| 1789 | less than 200,000 |

| 1851 | 481.000 |

| 2013 | 250.000 |

Purple colored are 16th century Huguenot territories on the map of France (in the borders of 1685). Light purple are disputed territories in French religious wars. Listed are places de sûreté protestantes. Colored blue are mostly German-speaking Lutheran areas of Alsace, which France annexed in 1648.

Search within the encyclopedia