House of Lords

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see House of Lords (disambiguation).

The House of Lords (also House of Peers), German Herrenhaus, usually called British House of Lords, is the upper house of the British Parliament. The Parliament, the British sovereign, also includes the House of Commons and the monarch. The House of Lords consists of two classes of members, the secular lords (Lords Temporal) and spiritual lords (Lords Spiritual). The vast majority of the current 794 members of the House of Lords (2020) are now life peerage nobles. They are appointed by the monarch on the advice of the Prime Minister or the House of Lords Appointments Commission and cannot inherit their title. Until the late 20th century, however, Lords Temporal were nobles with hereditary titles (hereditary peers). It was not until the Life Peerages Act 1958 that the possibility of appointing Lords without hereditary title with a seat in the House of Lords was created. The House of Lords Act 1999 fundamentally reformed the House of Lords and limited the number of hereditary peers to just 92. The spiritual Lords are made up of two archbishops and 24 bishops of the Anglican Church. The Lords Spiritual hold their seat as long as they hold their ecclesiastical offices. The secular Lords, on the other hand, hold their seat for life.

The House of Lords formed in the 14th century and has existed almost continuously since. The name was not used until 1544. It was abolished in 1649 by the revolutionary government that came to power during the English Civil War, but was re-established in 1660. It was once more powerful than the House of Commons, hence the name House of Lords for the House of Lords and House of Commons for the House of Commons. Since the 19th century its powers have steadily declined. It is now vested with far fewer powers than the House of Commons, which now has the final say on all questions: since the Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949, the House of Lords can only delay the coming into force of many laws for a maximum of twelve months; but it can no longer cause them to fail altogether. Such a power is known in political science as a suspensive veto. The House of Lords has no influence at all on all laws regulating financial matters (money bills), including the national budget. Further reforms were made under the House of Lords Act 1999, which virtually eliminated hereditary peers' hereditary seats. Through an electoral process within the House of Lords, 90 hereditary peerages were elected as peers representative of this group, and have since held just over one-tenth of the seats in the House of Lords. Two other peers with an hereditary title retained their seats because they held one of the Great Officers of State. On 7 March 2007, a majority of the House of Commons voted in favour of a motion to have only elected members for the House of Lords. The motion has not yet been passed as legislation, but could be implemented without the approval of the House of Lords in the event of parliamentary reform.

The House of Lords once had judicial powers. Thus, it was for a long time the highest reviewing body for most court proceedings in the United Kingdom. However, the judicial functions of the House of Lords were not exercised by the whole House, but by a fairly small group of members with legal experience. These were called lord justices (law lords). The House of Lords was not the only court of review (court of last resort) in the United Kingdom. In some matters this role fell to the Privy Council. The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 transferred the judicial functions of the House of Lords to a newly created Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, which met for the first time in autumn 2009.

The full title of the House of Lords is: "The Right Honourable The Lords Spiritual and Temporal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in Parliament Assembled". The House of Lords, like the House of Commons, meets in the Palace of Westminster in London.

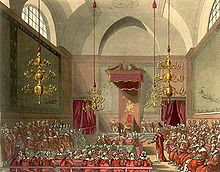

House of Lords Chamber

History

Middle Ages and early modern times

Parliament developed in the Middle Ages from the council that advised the king. This crown council consisted of clerics, nobles and representatives of the counties. Later, the representatives of the cities and boroughs were also added. The first parliament is often considered to be the Model Parliament, which met in 1295. It included archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, barons and representatives of the counties and boroughs. The power of Parliament slowly increased and changed during periods when the power of the Crown was increasing or decreasing. For example, during the reign of King Edward II from 1307 to 1327, the nobility was the most powerful authority in the realm, the crown was weak, and the representatives of the shires and boroughs were entirely powerless. In 1322, for the first time, the authority of Parliament was recognised not by custom or a royal charter, but by a statute passed by Parliament itself, which claimed legal validity. Further developments occurred during the reign of Edward III, the successor to Edward II. At this time, for the first time, Parliament was clearly divided into two chambers: the House of Commons, containing the representatives of the counties and cities, and the House of Lords, containing the chief clergy and nobles. Parliament's authority continued to grow, and by the early 15th century both chambers wielded unprecedented power. The Lords were far more powerful than the House of Commons, stemming from the great influence of the aristocrats and prelates in the kingdom.

The power of the nobility experienced a serious break during the Wars of Succession of the late 15th century, which went down in history as the Wars of the Roses. Most of the nobility either perished on the battlefields or were executed for their involvement in the war of succession. Many noble estates fell to the crown. Also, the age of feudalism was coming to an end, and the feudal armies controlled by the barons were becoming less important. Therefore, the Crown could easily regain absolute supremacy in the kingdom. The supremacy of the monarchs grew even more during the reigns of the Tudor monarchs in the 16th century. The Crown attained its greatest power during the reign of Henry VIII. (1509–1547).

The House of Lords remained more powerful than the House of Commons, but the House of Commons increased its influence. It reached the zenith of its power in relation to the House of Lords in the middle of the 17th century. Conflicts between the king and Parliament, and here especially with the House of Commons, eventually led to the EnglishCivil War during the 1640s. In 1649, after the defeat and execution of King Charles I, a republic was proclaimed, the Commonwealth of England. But in reality, the nation was under a dictatorship of Oliver Cromwell. The House of Lords degenerated into a largely powerless body. The government was controlled by Cromwell and his supporters in the House of Commons. On March 19, 1649, the House of Lords was abolished by an Act of Parliament that stated, among other things, "The [House of] Commons of England [finds] by too long experience that the House of Lords is useless and dangerous to the people of England." As a result, the House of Lords did not meet again until the Convention Parliament of 1660, at which the monarchy was reinstated. It regained its former position as the more powerful chamber of Parliament. It retained this position until the 19th century.

The 19th century brought several changes to the House of Lords. The number of members of the House of Lords, which had once been a body of only 50, had grown greatly through the generosity of George III and his successors in establishing titles of nobility. The individual influence of a parliamentary lord had been correspondingly diminished. Moreover, the power of the House of Lords had diminished in comparison with the House of Commons. Particularly noteworthy in the emergence of the leading position of the House of Commons was the Reform Act crisis of 1832. The electoral system for the House of Commons at this time was not yet fully democratic: only a portion of the population had the right to vote because of certain property requirements, and constituency boundaries had not been adjusted for centuries to reflect the actual distribution of population. Entire large cities like Manchester did not have a single representative in the House of Commons, while the 11 residents of Old Sarum were even allowed to elect two representatives. Representatives of small boroughs were susceptible to bribery and were often under the control of a local patron whose candidate was always guaranteed to win the election. Some aristocrats were even the patrons of numerous "west pocket boroughs" (pocket boroughs) in this way. In this way they controlled a considerable number of MPs in the House of Commons.

Reform Act of 1832

→ Main article: Reform Act 1832

The House of Commons attempted to remedy these anomalies in 1831 by passing a Reform Bill. At first, the House of Lords proved unwilling to pass the bill. However, it was forced to give way when Prime Minister Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey advised King William IV to appoint a large number of new members to the House of Lords who were favourably disposed to the Bill. At first the King balked at the suggestion, but then went along with it. However, before the King could move to action, the Lords passed the 1832 Act. The Lords, who were opposed to the Reform Act, conceded defeat and abstained, allowing the Act to pass. The Reform Act of 1832 disfranchised towns that had lapsed into insignificance (rotten boroughs), created a level playing field for voting in all towns, and gave proper representation to towns with large populations. It preserved, however, many of the west pocket boroughs. In the years that followed, the House of Commons increasingly claimed decision-making powers, while the influence of the House of Lords had suffered as a result of the crisis in the wake of the Reform Act. Also, the power of the patrons in the west pocket boroughs had diminished. The Lords were now increasingly reluctant to throw out legislation that had been passed by large majorities in the House of Commons. It was also becoming a generally accepted political practice that the support of the House of Commons alone was sufficient for the Prime Minister to remain in office.

Act of Parliament 1911

→ Main article: Parliament Act

The status of the House of Lords came into focus again in 1906, when the Lords - for the last time in British history - brought down a bill. The Liberal government elected that year (1906), led by Herbert Henry Asquith, introduced a series of social welfare programmes in 1908. Together with the costly arms race with Germany, this forced the government to raise revenue by increasing taxes. Therefore, in 1909, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, presented what he called a "People's Budget", which included higher taxes on wealthy landowners. However, this measure, unpopular with the aristocracy, was rejected in the predominantly Conservative House of Lords.

In the campaign for the 1910 election, therefore, the Liberals made the powers of the House of Lords their main campaign issue and thus achieved re-election. Asquith then proposed that the powers of the House of Lords should be very restricted. The legislative process was briefly interrupted by the death of King Edward VII, but resumed soon afterwards under George V. After further elections in December 1910, the Asquith government was able to get a bill through both Houses that would have seen a massive curtailment of the powers of the House of Lords. To break the foreseeable opposition of the Lords, they had resorted to a threat: The Prime Minister, with the monarch's approval, suggested that the House of Lords could be flooded with the creation of 500 new Liberal peers if it refused to pass the bill. This threatened coup de grâce was the same political vehicle that had already spurred the passage of the 1832 Reform Act, and forced the Lords' consent to their de facto removal from power. The Parliament Act 1911 came into force soon after, removing the legislative parity of the two Houses of Parliament. The House of Lords was henceforth only permitted to prorogue most legislative acts for a maximum of three parliamentary sessions, or for a maximum of 2 years. It was only allowed to delay Acts dealing with financial matters for a maximum of one month. The 1911 Act of Parliament was not intended to be a permanent solution; rather, more far-reaching measures were to be taken subsequently. Neither party pursued this matter with any zeal, however, and so membership of the House of Lords in particular remained largely hereditary. However, the 1949 Act of Parliament further restricted the suspensive power to either 2 parliamentary sessions or a maximum of one year. With the passage of the Parliament Act, the House of Commons had become the dominant branch of Parliament, both in theory and in practice.

Life Peerages Act of 1958

In 1958, the predominantly hereditary nature of the House of Lords was amended by the Life Peerages Act. This allowed the creation of non-hereditary baronies for life, with no numerical limits. Under the Labour government of Harold Wilson, a reform was attempted in 1968 whereby hereditary peers would still be allowed to remain in the House of Lords and participate in debates, but would no longer have voting rights. However, this reform failed in the House of Commons due to a combination of traditionalist Conservatives such as Enoch Powell and Labour MPs who supported the complete abolition of the House of Lords. When Michael Foot took over as leader of the Labour Party, abolition of the House of Lords became part of the party platform. Under the leadership of Neil Kinnock, reform of the House of Lords was then proposed instead. In the meantime, the creation of hereditary titles of nobility largely came to a halt. Exceptions were the conferral of peerage titles on members of the royal family and of three peerage titles during the reign of the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s. The last hereditary baronetcy to date was awarded to Denis Thatcher in 1991.

House of Lords Act 1999

Labour's return to government in 1997 under Tony Blair heralded a new round of reforms for the House of Lords. The Blair government introduced legislative proposals whereby all hereditary Lords would leave the House of Lords. This was to be a first step in reform. However, as part of a compromise, the government agreed to allow 92 hereditary peers to remain in the House of Lords until the reforms were completed. The remaining hereditary peers were eliminated when the House of Lords Act 1999 came into force. Most Lords abstained from the vote in the House of Lords. Only the Earl of Burford protested loudly and sat in protest on the Woolsack, which had been reserved for the Lord Chancellor since the 14th century.

Since then, however, the reform project has stalled. The Wakeham Commission proposed that 20% of the Lords should come from elections. However, this plan was criticised by many. A Joint Parliamentary Committee was set up in 2001 to deal with the matter, but it failed to reach a clear conclusion. Instead, the committee presented seven options for Parliament to choose from. According to these, the House of Lords was to be appointed outright, or elected at 20%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 80% each, or even outright. After a confusing series of votes in February 2003, all of these proposals failed, although the proposal for an 80% election was only three votes short of being accepted. Those MPs who were in favour of outright abolition voted against all the proposals. Another proposal was put forward by a group of MPs who favoured a 70% elected House of Lords, with the remaining seats to be appointed by a commission according to their personal skills, knowledge and experience. This proposal also failed to gain acceptance. This means that new peers will only be created by appointment to the House.

Reform attempts in the 21st century

The long-term goal of the reforms begun in 1998 by the Labour government under Tony Blair was the abolition of the House of Lords in its traditional form. It was to be replaced by a more democratically legitimised second chamber of parliament.

A first vote took place on 5 February 2003. The House of Commons rejected all the reform proposals on the table, ranging from a House of Lords composed entirely of appointed members to a House of Lords composed entirely of elected members. A complete abolition of the House of Lords was also rejected by a large majority.

In March 2007, there was a renewed debate and subsequent votes in both houses of Parliament on reform of the House of Lords. The House of Commons voted on several reform options on 7 March 2007. The choices were complete abolition of the House of Lords, or a House of Lords composed of 0, 20, 40, 50, 60, 80, or 100 percent elected members. Only the last two options received majority support, with the highest support being for a fully elected House of Lords. Prime Minister Blair had argued for a half-elected House of Lords. The House of Lords itself rejected the vote of the House of Commons and on 14 March 2007 voted by a large majority in favour of a future House of Lords continuing to be composed entirely of appointed members.

On November 1, 2014, then Labour Party leader Ed Miliband declared that if his party won the 2015 House of Commons election, it would abolish the House of Lords in its current form and replace it with an elected Senate. This would see senators elected by the English regions, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, countering the centralisation of the country. However, since the 2015 election resulted in a Conservative Party victory, Labour's reform plans are not expected to be implemented in the foreseeable future.

A report by the Electoral Reform Society, published on 16 August 2015 under the title House of Lords: Fact versus Fiction, criticised the House of Lords as not being an assembly of experts at all, but rather one of professional politicians. It was a "shockingly out of date and unrepresentative institution". A third of its members were former politicians, more than half were over 70 and nearly half resided in London or the south-east of England. The report also faulted some Lords for claiming expenses for services they had demonstrably not provided.

In 2017, a House of Lords committee presented a list of recommendations for its reform. It is to be reduced in size and the previously lifelong mandate of members is to be limited to 15 years. Since then, this project has been dormant.

The new Lords Chamber (recorded between 1870 and 1885)

The House of Lords is located on the left underneath the Victoria Tower of the Palace of Westminster.

Vote in the House of Lords on the Parliament Act 1911.

Queen Anne delivers a speech from the throne to the House of Lords, c. 1708-14.

The Lords Chamber, the Council Chamber of the House of Lords in the Palace of Westminster, in 1811.

Throne in the Lords Chamber, from where the British monarch delivers his speech at the opening of Parliament

Features

As part of the legislature

The main role of the House of Lords is to scrutinise laws made by the House of Commons. It can propose amendments or new laws. It has the right to defer new laws for one year. However, the number of vetoes is limited by common law. The Lords may not block the state budget or laws that have already had their second reading (Salisbury Convention). Repeated use of the veto can be stopped by the House of Commons with the Parliament Act.

As court (former function)

The House of Lords was traditionally not only part of the legislature, but also the highest court of appeal in civil matters for the whole of the United Kingdom, and in criminal matters for England, Wales and Northern Ireland (Scotland has its own supreme criminal court). However, the identity of the House of Lords as both a parliamentary chamber and a court was more formal: from the 19th century onwards, it was customary to appoint experienced lawyers as barons for the sole purpose of promoting them to the House of Lords as judges. There they were known as Law Lords (officially, Lords of Appeal in Ordinary) and formed a committee of the House of Lords (Appellate Committee of the House of Lords) which dealt with appeals instead of the full House. Conversely, the custom developed of Law Lords not exercising their membership of the House of Lords in relation to its political functions in order to preserve their judicial independence. In practice, therefore, the functions of the House of Lords as a court and as a parliament were separate, even if in constitutional fiction they were exercised by the same body. The last time non-legally educated members of the House of Lords voted on a revision case was in 1832.

In the course of the various constitutional reforms under New Labour, the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 also ushered in the end of the House of Lords' position as a court. Instead, a separate Supreme Court of the United Kingdom was created to take over the judicial function of the House of Lords. It met for the first time in the autumn of 2009. The Law Lords became members of the new Supreme Court, which is headed by a President (President of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom). The judicial functions of the House of Lords as the highest court of appeal were transferred to the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. The House of Lords Appellate Committee, which had previously been responsible for this function, was abolished altogether when the Court took up its work on 1 October 2009.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the House of Lords?

A: The House of Lords is one of the two Houses of Parliament of the United Kingdom (UK).

Q: Where is the House of Lords located?

A: The House of Lords is located in London, the capital city of the UK.

Q: What is the other house that forms the government and parliament of the UK?

A: The other house that forms the government and parliament of the UK is the House of Commons.

Q: Is the House of Lords elected?

A: No, the House of Lords is not elected (voted for).

Q: Who are the holders of the seats reserved for hereditary peers?

A: The holders of the seats reserved for hereditary peers are chosen by the House or by other hereditary peers in their parties.

Q: Can hereditary peers be elected into the House of Lords?

A: Yes, hereditary peers can be elected into the House of Lords if they are chosen by the House or by other hereditary peers in their parties.

Q: How are the two houses of Parliament of the UK related to each other?

A: The two houses of Parliament of the UK are related to each other as together, they form the government and parliament of the UK.

Search within the encyclopedia