House of Commons of the United Kingdom

![]()

This article is about the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. For other meanings, see House of Commons (disambiguation).

The House of Commons (HoC), in German usually called the British House of Commons (officially: The Honourable the Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland assembled in Parliament), is the politically decisive second chamber of the British Parliament. The House of Commons determines legislation and the national budget, the government of the United Kingdom is responsible to it, and a prime minister remains in office only as long as he has its support. In addition to the House of Commons, Parliament includes the Crown and the House of Lords, the House of Lords. Both chambers meet in the Palace of Westminster.

The House of Commons consists of 650 Members of Parliament (MPs). Members of Parliament are elected by relative majority in their respective constituencies, the Constituencies, and hold office until the dissolution of Parliament. The Fixed-term Parliaments Act of 2011 sets a term of five years. Early dissolution of the House of Commons is only possible by a two-thirds majority vote of Parliament or a vote of no confidence. Most ministers are also members of the House of Commons, as have all prime ministers since 1963.

The origin of today's House of Commons is considered to be De Montfort's Parliament of 1264, a council of the king, which for the first time also included civil representatives. It developed into an independent chamber of the English Parliament decisively in the 14th century from the assembly of the representatives of the mostly trading cities and has existed continuously since then. At first only English members sat in the House of Commons. Since the 16th century Welsh members were added, since the Act of Union in 1707 Scottish members and since 1801 also Irish members. At the beginning of its history, the House of Commons was the least important part of Parliament. From the 17th century, however, largely as a result of the English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution, it gradually rose to become the dominant branch of the legislature. Its powers today exceed those of both the Crown and the House of Lords. Since the Parliament Act of 1911, the House of Lords can no longer reject bills from the House of Commons, but can only veto them with a suspensive veto.

History

Origin and development until the early 19th century

Parliament developed from the Royal Council, which advised the king during the Middle Ages. This council, which always met for short periods of time, consisted of clerics, peers and representatives of the counties, known as knights of the shire. The most important task of the Council was to agree to taxes proposed by the Crown. Often, however, the Council required complaints from the people to be redressed before it went to a vote on taxation. Legislative powers evolved from this.

In the Model Parliament of 1295 representatives of the Boroughs, i.e. the country towns and cities, were also admitted. Thus it became the custom for each county to send two knights (Knights of the Shire) and each town two burgesses (Burgesses). At first the representatives of the towns were almost entirely powerless. While the representation of the shires was fixed, the monarch could give or take away the right of suffrage from the towns at his pleasure. Any visible aspiration for independence by the citizens would have led to the exclusion of their town from parliament. The knights of the shire were in a better position, but even they were less powerful than their fellow high nobles in the parliament, which still consisted of one chamber. The division of Parliament into two houses occurred in 1341 during the reign of Edward III, with the knights and burgesses forming the House of Commons, and the clergy and high nobles forming the House of Lords.

Although it remained subordinate to both the crown and the lords, the House of Commons acted with increasing boldness. During the Good Parliament (1376), the Speaker of the House of Commons, Sir Peter de la Mare, complained about the oppressive tax burden, demanded an accounting of royal expenditures, and criticized the king for his management of the military. The House of Commons even set about removing some of the royal ministers. The brave speaker was imprisoned, but released soon after the death of King Edward III. During the reign of the next monarch, Richard II, the House of Commons again began to remove errant ministers of the crown. It insisted on being allowed to control not only taxation but also public expenditure. Despite these gains in authority, the House of Commons nevertheless remained less powerful than the House of Lords and the Crown.

The influence of the crown increased still further through the civil wars of the late 15th century, while the importance of the high nobility declined. In the years that followed, the two Houses of Parliament retained little power, and the absolute supremacy of the monarch was renewed. In the 16th century, under the Tudor dynasty, the power of the crown actually increased. On the other hand, King Henry VIII, at the instigation of his senior minister Thomas Cromwell, for the first time granted Parliament a say in church and constitutional matters in order to achieve the separation of the English Church from Rome. From 1603, after the House of Stuart came to power, both the absolutist aspirations of the Crown and the self-confidence of Parliament continued to increase. Under the first two Stuart monarchs, James I and Charles I, the Crown increasingly came into conflict with the House of Commons over taxation, religion and royal powers.

Under Charles I, these disputes took such fundamental forms that they could only be decided by the English Civil War. After the victory of the parliamentary army under Oliver Cromwell, the king was condemned as a traitor and beheaded in 1649. The House of Commons abolished the Crown and House of Lords and established the English Republic for 11 years. Although in theory it was the supreme organ of the state, Cromwell ruled quasi-dictatorially as Lord Protector. Therefore, in 1660, two years after his death, there was a restoration of the monarchy and the House of Lords. King Charles II had to make concessions to the House of Commons, which his father had strictly refused. His brother and successor James II was declared deposed in 1688 in the course of the Glorious Revolution. Despite continuing to have strong powers, subsequent kings had to be careful to conduct politics in accordance with the parliamentary majority of the House of Commons.

In the 18th century, the office of prime minister emerged. Soon, the modern view prevailed that the government remained in power only as long as it had the support of Parliament. However, it was not until later that the support of the House of Commons became crucial to the government. The custom of the Prime Minister coming from the House of Commons also developed later.

The House of Commons underwent an important period of reform in the 19th century. The Crown had made very irregular use of its prerogative to grant and withdraw suffrage from the cities. Further, some anomalies had developed in city representations. Thus some once significant towns had slipped into insignificance, so-called rotten boroughs. Yet they had retained their right to send two representatives to the House of Commons. The most notorious example was Old Sarum, which had only 11 electors. In all, there were 46 constituencies with fewer than 50 electors, 19 others with fewer than 100 electors, and another 46 with fewer than 200 electors. At the same time, large cities such as Manchester did not have their own representatives, but their eligible residents could vote in the relevant county, in this case Lancashire. There were also what were known as 'west pocket boroughs' - small constituencies controlled by a few wealthy landowners and nobles whose candidates were invariably elected. In this way, for example, the respective Duke of Norfolk held eleven parliamentary seats, and the Earl of Lonsdale nine. These mandates were given to younger sons, but could also be sold or let, e.g. for £1,000 a year.

Reform Act of 1832

→ Main article: Reform Act of 1832

The House of Commons attempted to remedy these anomalies in 1831 by passing a Reform Bill. At first, the House of Lords proved unwilling to pass the bill. However, it was forced to give way when Prime Minister Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey advised King William IV to appoint a large number of new members to the House of Lords who were favourably disposed to the Bill. However, before the King could act, the Lords passed the Act in 1832. The Reform Act of 1832 disenfranchised cities that had lapsed into insignificance, created a level playing field for elections in all cities, and gave cities with large populations adequate representation. It preserved, however, many of the west pocket boroughs. In the years that followed, the House of Commons increasingly claimed decision-making powers, while the influence of the House of Lords had suffered as a result of the crisis in the wake of the Reform Act. The power of the patrons in the west pocket boroughs had also diminished. The Lords were now increasingly reluctant to throw out legislation that had passed with large majorities in the House of Commons. It also became a generally accepted political practice that the support of the House of Commons alone was sufficient for the Prime Minister to remain in office.

Many other reforms were introduced during the second half of the 19th century. The Reform Act of 1867 lowered the property threshold at which someone was eligible to vote in cities, reduced the number of representatives from less populated cities, and granted new parliamentary seats to several emerging industrial cities. The electorate was expanded by the Representation of the People Act of 1884, which lowered the required property threshold for voting in counties. The Seat Redistribution Act of the following year replaced almost all constituencies with multiple representatives with constituencies with only one representative.

Parliament Act of 1911

The next important phase in the history of the House of Commons came in the early 20th century. The Liberal government, led by Herbert Henry Asquith, introduced a series of social welfare programmes in 1908. Together with the costly arms race with Germany, the government was therefore forced to raise revenue through tax increases. Therefore, in 1909, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, presented a so-called "People's Budget", which provided for higher taxes on wealthy landowners. However, this unpopular measure was rejected in the predominantly Conservative House of Lords.

In the campaign for the election of 15 January / 10 February 1910, the Liberals made the powers of the House of Lords their main campaign issue and thus achieved re-election. Asquith then proposed that the powers of the House of Lords be greatly reduced. The legislative process was briefly interrupted by the death of King Edward VII in May 1910; it was soon resumed under George V. After the House of Commons election in December 1910, the Asquith government was able to push through the bill that curtailed the powers of the House of Lords. The Prime Minister, with the monarch's approval, proposed that the House of Lords might be flooded with the creation of 500 Liberal peers, provided it refused to pass the Bill. The same measure had already made possible the passage of the Reform Act of 1832. The Parliament Act 1911 came into force soon afterwards and removed the legislative parity of the two Houses of Parliament. The House of Lords was now only permitted to prorogue most legislative acts for a maximum of three parliamentary sessions, or for a maximum of 2 years. The 1949 Parliament Act further restricted this to either two parliamentary sessions or a maximum of one year. With the passing of these Acts, the House of Commons has become the more powerful chamber of Parliament.

Originally, MPs received no income for their office. Most who were elected to the House of Commons had private incomes, while a few depended on the financial support of wealthy patrons. Early Labour MPs often drew income from a trade union, but this was banned by a House of Lords decision in 1910. As a consequence, a clause was inserted into the 1911 Act of Parliament which introduced diets for MPs. Government ministers had been paid before.

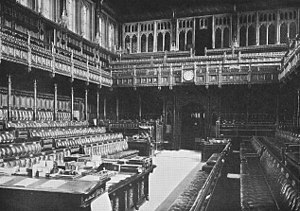

Chamber of the House of Commons in 1851

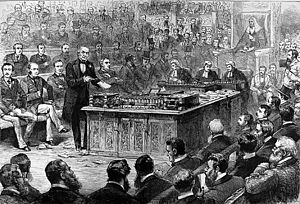

William Gladstone during a debate in the House of Commons on April 8, 1886.

_b_565.jpg)

House of Commons, illustration from 1854

William Pitt the Younger giving a speech in the House of Commons, painting by Anton Hickel

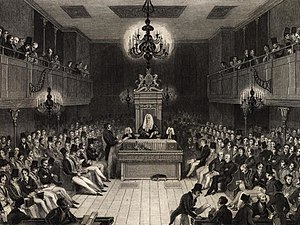

House of Commons, drawing from 1834

Deputies and elections

Each MP represents a single constituency. Before the reforms of the 19th century, there was little relationship between constituencies and population distribution. The counties and towns, with their defined boundaries, were largely evenly represented in the House of Commons by two representatives each. The reforms of the 19th century led to a more equal distribution of seats. This began with the Reform Act of 1832, and the reforms of 1885 replaced most constituencies with two MPs with those with only one. The last constituencies with two MPs were transformed in 1948. University constituencies, which had given the important universities of Oxford and Cambridge their own representation in Parliament, were also abolished in the same year. Since then, each constituency has elected only one MP to the House of Commons.

Division of the constituencies

The number of constituencies allocated to each of the four regions of the United Kingdom is a function of their number of eligible voters. There are certain specifications to be taken into account: Northern Ireland must have between 16 and 18 constituencies. Wales must by law send at least 35 MPs to Parliament. Special rules apply to the islands (Isle of Wight, Scottish Islands, etc.) as regards the size of constituencies.

Constituency boundaries are set by four permanent and independent Boundary Commissions, one each for England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. The commissions regularly review the number of eligible voters in the constituencies and propose changes to the constituency boundaries in line with changes in these figures. In drawing constituency boundaries, the Boundary Commissions take into account, among other things, local administrative boundaries. Their proposals are subject to the approval of Parliament, but cannot be changed by Parliament itself.

The requirement is to delimit the constituencies so that the number of eligible voters in the coming election does not deviate by more than 5% from the arithmetic mean. In 2016, there were 74,769 eligible voters per constituency, meaning that there should be no less than 71,031 eligible voters and no more than 78,507 per constituency. We are still far from this target. In 2015, there were major deviations from the ideal of having as equal a number of eligible voters as possible in the constituencies: As of 1 December 2015, the Arfon constituency in Wales had only 38,083 eligible voters. By contrast, the two largest constituencies (Ilford South and Bristol West) had more than 91,000 eligible voters in 2015.

The United Kingdom is (as of 2016) divided into 650 constituencies, of which 533 are in England, 40 in Wales, 59 in Scotland and 18 in Northern Ireland. The House of Commons decided to reduce the number of constituencies to 600 by the next election.

Election date and conduct of the election

Until 2011, the Prime Minister was allowed to choose when to dissolve Parliament and thus when to call a new election within a 5-year period, unless forced to do so by a failed confidence vote. The Tories-Liberal Democrats government under Prime Minister Cameron changed this with the Fixed-Term Parliaments Act. Since then there has been a fixed election date. This should preferably be 5 years after the last election date, on the first Thursday in May. However, the Prime Minister can bring a bill into parliament that he wants to dissolve the parliament, if this is accepted, it comes to new elections. There are also new elections if the House no longer has confidence in Her Majesty's Government.

Each candidate must submit application forms signed by 10 registered voters of his constituency. He must also deposit 500 pounds, which will be returned only if the candidate obtains at least 5% of the votes of his constituency. This deposit is to prevent joke candidacies. One MP from each constituency is sent to the House of Commons. According to the principle of majority voting, the candidate who receives the most votes in his constituency wins. The votes of the losing candidates are not taken into account. Minors, members of the House of Lords, prisoners and legally incompetent persons are not entitled to vote. To vote, one must be a resident of the United Kingdom as well as a citizen of the same, a British Overseas Territory, the Republic of Ireland or a member state of the Commonwealth of Nations. British citizens living abroad are also eligible to vote for up to 15 years after leaving the UK. No voter may vote in more than one constituency.

Parliament's term of office

Once elected, the MP serves regularly until the next dissolution of Parliament (or until his/her death). Provided an MP loses the qualifications below, their seat becomes vacant. There is also the possibility of the House of Commons disqualifying MPs. However, this option is only used in rare exceptional circumstances, such as serious misconduct or criminal activity. In such cases, a vacancy can be removed by a by-election in the relevant constituency. The same electoral system is used as for the general election.

The term "Member of Parliament" refers only to members of the House of Commons, although members of the House of Lords are also part of Parliament. Members of the House of Commons may add the abbreviation MP (Member of Parliament) after their name.

Income of Members of Parliament

The annual salary of each member of the House of Commons has been £79,468 since April 2019. This is the equivalent of approximately 95,000 euros per year (or just under 8,000 euros per month). On top of this, there may be additional salaries for offices they hold in addition to their mandate, such as Speaker. Most MPs receive between £100,000 and £150,000 for various expenses (staff costs, postage, travel expenses, etc.) as well as for maintaining a second home in London if they live elsewhere.

Eligibility

There are numerous requirements that candidates for parliamentary office must meet. The most important are that an MP must be over 18 years of age and a citizen of the United Kingdom, a British Overseas Territory, the Republic of Ireland or a national of another Commonwealth country. These restrictions were established by the British Nationality Act 1981. Prior to this, even narrower requirements applied: Under the Act of Settlement of 1701, only those who had already become British citizens at birth were allowed to stand. Members of the House of Lords were not allowed to become members of the House of Commons.

Members of Parliament are excluded from the House of Commons if they are subject to restrictions arising from personal bankruptcy (Bankruptcy Restrictions Order). This applies to MPs from England and Wales. Northern Irish MPs are excluded if they have been declared insolvent, and Scottish MPs if their assets are subject to foreclosure. The mentally ill are also barred from sitting in the House of Commons. Under the Mental Health Act 1959, two specialists must declare to the Speaker of the House of Commons that the MP concerned is suffering from mental illness before his or her seat can be declared vacant. There is also an 18th century common law precedent that the "deaf and dumb" may not sit in the House of Commons. However, this precedent has not been decided in recent years and it seems highly unlikely that it would be upheld by the courts in a hypothetical decision.

Any person found guilty of high treason shall be ineligible to sit in Parliament until he has served his sentence in full, or until he has been granted a full pardon by the Crown. Also, those serving a prison sentence of one year or more are ineligible. Last but not least, those guilty of certain election-related offences against the Representation of the People Act 1983 are ineligible to stand for 10 years. In addition, there are other disqualifying offences in the House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975. Holders of high judicial office, members of the civil service, professional soldiers and members of foreign legislative bodies (other than those of Ireland or the Commonwealth states), as well as office holders of various Crown offices, are also ineligible to stand for the House of Commons. The Act largely consolidated previously made statutory rules. For example, several Crown officials had already been disqualified since the Act of Settlement of 1707. Although ministers are also paid officials of the Crown, they are allowed to exercise their parliamentary mandate.

The rule barring certain Crown officials from serving in the House of Commons was enacted to circumvent another House of Commons ruling in 1623 that MPs were not permitted to resign. Nowadays, should an MP wish to resign, they can apply for an appointment to one of two Crown Offices. These are the offices of Crown Steward and Bailiff of the Manor of the Chiltern Hundreds and Crown Steward and Bailiff of the Manor of Northstead. The Chancellor of the Exchequer is responsible for the appointment and is bound by tradition never to refuse such a request.

Search within the encyclopedia