Anschluss

The "Anschluss" of Austria, or "Anschluss" for short, has been used since 1938 to refer primarily to the processes by which Austrian and German National Socialists arranged for the incorporation of the federal state of Austria into the National Socialist German Reich in March 1938.

In the night of 11 to 12 March 1938, following telephone threats by Hermann Göring, Austrian National Socialists replaced the Austrofascist Ständestaatsregime even before the invasion of German troops. From 12 March onwards, Wehrmacht, SS and police units took command. The National Socialist Federal Government under Arthur Seyß-Inquart, appointed that night by Federal President Wilhelm Miklas, administratively carried out the "Anschluss" on 13 March 1938 on behalf of Adolf Hitler, who had arrived in Austria the day before. He successively brought about the complete absorption of Austria into the German Reich and the participation of many Austrians in the National Socialist crimes. Considerable parts of the Austrian population greeted the Anschluss with jubilation; for others, especially Austria's Jews, the Anschluss meant disenfranchisement, expropriation and terror.

The Federal Constitutional Law on the Reunification of Austria with the German Reich, passed by the Federal Government on 13 March, ended the legal existence of the dictatorial Austrian federal state. The Republic of Austria, re-established in 1945, considers the "Anschluss" ex tunc (from the beginning) to be null and void. Its statehood and the consequences for the continued existence of Austria in the years 1938 to 1945 are disputed.

The rule of National Socialism lasted in Vienna and the surrounding area until the Red Army conquered Vienna in mid-April 1945. The "Anschluss" was declared "null and void" in the Declaration of Independence of 27 April 1945. In many other parts of Austria, the Nazi regime did not end until the end of the Second World War in May 1945; for example, Innsbruck, the capital of Tyrol, was handed over to the invading US Army units on 3 May 1945 by Austrian resistance fighters who had replaced the Nazi regime.

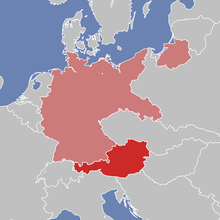

Austria and the German Reich (March 12, 1938)

Dismantling of a turnpike, March 1938

Previous story

Challenged by Napoleon, Francis II accepted his conditions and in 1804 accepted "for Us and Our Successors [...] the title and dignity of hereditary Emperor of Austria". That was the end of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, which was formally confirmed in 1806. Consequently, the German (today often: German-speaking) hereditary lands of Austria (as well as the lands of the Bohemian Crown) and the other states that connected them were divided: Thus, in 1815, at the Congress of Vienna, the German Confederation was formed as a new political union. This loose union of 41 individual German states, however, did not do sufficient justice to the aspirations for a unified state.

As a result, different solutions emerged to achieve this goal: on the one hand, the Greater German Solution, a new, strongly federalist German state under the leadership of the House of Habsburg, the historic Roman-German imperial house, including the German lands of the Empire of Austria (which would have meant that the Habsburgs' Danube monarchy would have been divided by the German external border) - and, on the other hand, the so-called Small German Solution under the hegemony of the Kingdom of Prussia.

The inclusion of the German part of Austria in a German national state was already discussed in the Frankfurt National Assembly of 1848/49. Archduke Johann of Austria was elected Reichsverweser by it in the sense of the Greater German solution. In his speech of March 13, 1849, the constitutional historian Georg Waitz opposed the combination of German and non-German "nations" in the Habsburg "total monarchy" and said that German-Austrian deputies should consider it their task to prevent the hereditary emperorship, so that at least for the future an entry of Austria would be possible.

The small German solution was realized after the victories of Prussia and its allies over Austria in the War of 1866 and over the Empire of France in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71. In 1871, the German Empire was proclaimed at the Palace of Versailles near Paris as the Kaiserreich, the union of German principalities and kingdoms led by Prussia but without Austria.

Interpretation of the connection requests

Friedrich Heer traced the desire of the German-speaking population of the former Habsburg hereditary lands to the time of the Counter-Reformation and sees it as closely linked to the centuries-long political and religious confrontation between Protestant northern Germany and Catholic, multilingual Austria, which was subsequently supported by the major European powers of Prussia and the Habsburg monarchy. Protestants saw in the Protestant north of the "German Empire" redemption from what they perceived as "incarceration" by the pope and the emperor. According to Heer, the first centre of an independent Austrian national consciousness was Vienna, which was opposed by rebellious provinces, by Upper Austria, Carinthia, Styria, as the multicultural residence of the supranational Habsburgs. This thesis is empirically supported by proving that Upper Austria was a main area of resistance at the time of the Peasants' Wars and that centuries later, at the time of the Nazi coup attempt, a particularly large number of illegal National Socialists were active in Vienna.

aspirations of affiliation after the First World War

The end of the First World War brought the downfall of the imperial and royal monarchy. Monarchy and at the same time the break-up of the predominantly Catholic multi-ethnic state of Austria-Hungary. In accordance with Emperor Charles I's People's Manifesto for Cisleithania, the new state of German Austria was founded on 30 October 1918, even before the armistice of Villa Giusti on 3 November 1918, which the representatives of the new state wanted nothing to do with: Asked by the Emperor, they simply did not take a position on it.

On November 22, 1918, the Republic of German Austria defined its (desired) national territory, the borders of which, however, had not yet been recognized in a peace treaty with the victorious powers or by the neighboring countries. German Bohemia and the Sudetenland were also part of it, as were the German language islands of Brno, Iglau and Olmütz.

The Provisional National Assembly and the provisional German-Austrian government, an executive committee appointed from among its members and known as the Council of State, saw the only possibility of political existence in a constitutional union with the German Empire, which was now also republican, especially because it became clear that the other successor states to the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy were not interested in a loose confederation either.

German Austria and the Weimar National Assembly

As early as 9 November 1918, six days after the armistice between Austria-Hungary and the Entente power Italy, the Provisional National Assembly turned to the German Reich Chancellor with the request to include German Austria in the reorganization of the German Reich. The next day the Provincial Committee for German Bohemia joined in this request. On November 12, 1918, the Law on the Form of State and Government was unanimously adopted by the Provisional National Assembly for German Austria amid jubilation. Its second article read: "German Austria is a constituent part of the German Republic".

Until then, most active politicians had thought in larger dimensions (of the previous Cisleithania) than those of a small state. In view of the fact that economically important regions were henceforth no longer part of the national territory, "Restösterreich" appeared to them to be unviable. The hunger winters of 1918/19 and 1919/20 dramatized this viability debate.

Not only German nationalist sentiments played a role in this. The Social Democrats, for example, feared - and rightly so, as it later turned out - that they would be put on the defensive politically in German Austria, which was dominated by rural conservatives, and hoped for the implementation of socialism within the framework of the German Republic. Among the Christian Socialists, on the other hand, aversion to the Viennese centralism so perceived played a not insignificant role. What was advocated in many cases was not a unilateral annexation, as it was finally carried out in 1938, but a union of equal federal states.

The German Austrians had been used to living in an imperial empire for centuries and could not identify with the new small state. In this situation, the claim was launched and constantly nurtured, psychologically clever, that the relatively small Remnant Austria was not economically viable. In fact, however, significant economic enterprises and branches remained in the country.

The German reaction to the vote of the provisional Austrian National Assembly of November 1918 for the Anschluss was positive. On November 30, 1918, the Council of People's Deputies, under its chairman Friedrich Ebert, announced in Article 25 of the Ordinance on the Elections to a Constituent National Assembly that if the German National Assembly decided to incorporate German Austria into the German Reich in accordance with its wishes, its deputies would join the German National Assembly as members with equal rights. Citizens of German Austria were given the right to participate in these elections. The Act on the Provisional Power of the Reich, the emergency constitution submitted by the People's Deputies Ebert and Scheidemann, already proposed the first measures for Austria's participation in the German legislature. According to § 2, Austria was to participate in an advisory capacity before joining the German Reich.

The German National Assembly and its Constitutional Committee passed the corresponding resolution in February and March 1919. A similar provision was also included in Article 61 (2) of the Weimar Constitution. According to the "Anschluss Protocol" signed by the two Foreign Ministers Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau and Otto Bauer on 2 March 1919, "German Austria was to enter the Reich as an independent constituent state". Areas with a German-speaking population, such as German Bohemia and the Sudetenland, were to be "annexed to the bordering German federal states".

The victorious powers criticized the Anschluss Protocol as a violation of the Treaty of Versailles accepted by the German Reich on June 28, 1919, and demanded that it be amended. The German representatives complied with this demand in a formal declaration of 18 September 1919: The constitutional provisions concerning German Austria, in particular concerning "the admission of Austrian representatives to the Imperial Council", were invalid until, if necessary, the "Council of the League of Nations will have agreed to a corresponding change in the international situation of Austria". In the Treaty of Saint-Germain, with the preservation of Austrian sovereignty which it stipulated and which was concluded in September 1919, a de facto insurmountable hurdle was erected for German Austria, which was recognized as the successor to (old) Austria, to unite with the German Reich. Germany was forced in the Treaty of Versailles to declare Article 61, para. 2, which had just been adopted and which allowed Austria an option of annexation, null and void (see "Anschlussverbot"). Thus the Allies doubly blocked Austria's annexation to Germany. At government level, the Anschluss was now no longer actively pursued for the time being. With the ratification of the peace treaty in October 1919, the state of German Austria changed its name to the Republic of Austria as prescribed.

For various reasons, however, the Anschluss remained a declared long-term goal, especially for the Greater German People's Party, the German National Movement, and the Social Democrats ("Anschluss an Deutschland ist Anschluss an den Sozialismus", slogan of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, the party's central organ). The Christian Social Party was also politically in favor of it.

Connection efforts in the Austrian provinces

While the Anschluss movement of 1918/19 was still strongly influenced by socialist politicians, in the following years it shifted to Christian-social and conservative-monarchist dominated countries in Austria, which wanted to break away from "Red Vienna".

Vorarlberg spoke out in a referendum in favour of annexation to Alemannic Switzerland, which was rejected by both the Swiss Federal Council and the Austrian state government.

After the failed attempt at restoration by the former Emperor Charles I, who had travelled to Hungary as King of Hungary from his exile in Switzerland on 26 March 1921 and attempted to take over the government again, resistance to the republican government in Vienna grew stronger, especially in the provinces still dominated by monarchist conservatives. With support from neighbouring Bavaria, where the socialist Munich soviet republic had been defeated two years earlier, the first Austrian home defence forces were formed in Salzburg and Tyrol. These vehemently advocated a merger with the now conservative-ruled Germany of the Weimar period. Even monarchists, who had earlier rejected the merger as a "Jewish invention", openly sought it together with the German nationalists.

The Tyrolean parliament held a vote in April 1921, in which a majority of 98.8 % voted in favour of the merger. A vote held in Salzburg on 29 May 1921 resulted in 99.3% of the votes cast being in favour.

Further votes were prevented by protests of the guarantors of the peace treaty, especially the French government. In the event that other federal states were to follow suit, threats were made to prevent foreign loans to the economically weakened Austria. Chancellor Michael Mayr (CS), who had demanded the cessation of all votes still planned in this regard, resigned on 1 June when the Styrian parliament announced that it would nevertheless hold a vote. He was succeeded by the German nationalist, non-partisan Johann Schober (also police chief of Vienna), who prevented further votes and referred those who wanted the merger to a later, more favourable time.

Geneva Protocols and Lausanne Protocol

The prohibition of annexation was reaffirmed in the Geneva Protocols of 4 October 1922 between the governments of France, the United Kingdom, Italy, Czechoslovakia and Austria - a precondition for the granting of loans by the League of Nations to Austria in the amount of 650 million gold crowns. Against the opposition of the Social Democrats, the National Council adopted the Geneva Protocols; they were a prerequisite for the containment of inflation and the change from the crown currency to the schilling, which took place in 1925.

The Anschlussverbot was the subject of another treaty in the 1932 Lausanne Protocol, where it was one of the conditions for the granting of another League of Nations loan that Austria had to take out to deal with the effects of the Great Depression.

Positions of the parties

All Austrian parties - including the Austrian Communist Party, which after a successful revolution demanded an annexation of "Soviet Austria" to "Soviet Germany" - were fundamentally in favor of unification with the German Reich before 1933. The Social Democratic Workers' Party of German Austria (SDAPDÖ), for example, still called for annexation "by peaceful means" to the German Republic in 1926 in its predominantly Marxist Linz Programme. However, it deleted the corresponding passage "in view of the changed situation in the German Reich due to National Socialism" at its party congress in 1933. The Christian Social Party (CS) as well as the Vaterländische Front (Patriotic Front), which emerged from it, also opposed annexation to the "Third Reich".

On the question of the Austrian Social Democracy, which had been banned in 1934, taking an active stand against the threat to Austria posed by National Socialism, there were clear statements in the so-called Socialist Trial of 1936: The defendant Roman Felleis declared that the workers would "stand up for this state in the future only when it has once again become a home for their rights, for their freedom. [...] Give us freedom, then you can have our fists!" Defendant Bruno Kreisky said at the trial, "Only free citizens will fight against bondage."

Austria and Nazi Germany 1933-1937

With the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) coming to power in Germany, the framework conditions changed fundamentally in 1933. Adolf Hitler, who as a native of Upper Austria had renounced his Austrian citizenship in 1925 and became a German citizen in 1932 at the age of 43, initially kept a low profile in foreign policy, despite the demand "German Austria must return to the great German motherland" already written down in his book Mein Kampf in 1924/25. He did not want to anger Benito Mussolini, since he was striving for an alliance with him.

On July 25, 1934, Austrian National Socialists led by SS Standarte 89 attempted what later became known as the July Putsch against the dictatorial Ständestaat, but it failed. Some of the putschists succeeded in penetrating the Federal Chancellery in Vienna, where Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß was so severely wounded by gunfire that he succumbed to his injuries a short time later, having been left without medical assistance. Hitler denied German involvement in the attempted coup. The Austrian national organization of the NSDAP, which had been banned since 1933, continued to receive support from the German Reich, but the German regime now increasingly moved to infiltrate the political system in Austria with confidants. These included, among others, Edmund Glaise-Horstenau, Taras Borodajkewycz and Arthur Seyß-Inquart.

After the beginning of the Italian aggression against Abyssinia, Great Britain demanded sanctions against Italy before the League of Nations in October 1935 and subsequently pursued the dissolution of the Stresa Front and the Locarno Treaties. Mussolini was thus isolated internationally and pushed to Hitler's side. For the Fatherland Front ruling in Austria, this meant the loss of an important patron, since Italy was the guarantor of Austria's state independence.

Federal Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg, successor to the assassinated Dollfuß, now had to look for ways to improve relations with the German Reich. On 11 July 1936 he concluded the July Agreement with Hitler. The German Reich lifted the one-thousand-mark ban imposed as a result of the 1933 ban on the NSDAP in Austria, National Socialists imprisoned in Austria were granted amnesty, and National Socialist newspapers were once again permitted.

In addition, Schuschnigg included National Socialist confidants in his cabinet. Edmund Glaise-Horstenau became Federal Minister for National Affairs, Guido Schmidt Secretary of State in the Foreign Ministry, and Seyß-Inquart was admitted to the Council of State. This was followed in 1937 by the opening of the Vaterländische Front to National Socialists. The NSDAP was able to reorganize itself in newly established "People's Political Departments", most of which were headed by National Socialists.

Kurt Schuschnigg (1936)

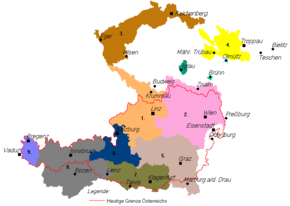

Territory of the Republic of German Austria claimed by the National Assembly (1918-1919)

Crisis 1938

The meeting at the Berghof

After the consolidation of his alliance with Mussolini, the Berlin-Rome axis in October 1936, and Italy's entry into the Anti-Comintern Pact in November 1937, it became increasingly clear that Austrian independence would no longer be an object of conflict between the two powers. Nevertheless, Hitler could not be entirely sure that Rome would accept Austria's annexation.

When Hitler explained his military plans to the Wehrmacht leadership on 5 November 1937, which was recorded in the so-called Hoßbach-Niederschrift, he named 1943 as the latest date for the annexation of Czechoslovakia (→ Zerschlagung der Rest-Tschechei) and Austria; under favourable circumstances, this could take place as early as 1938. At this point, Hitler was still planning to conquer Austria militarily. At the same time, however, he was still shying away from war. Thus, a few weeks after the meeting recorded by Friedrich Hoßbach, he declared on 16 December 1937 that he did not want a "fallow solution" to the Anschluss question "as long as this is undesirable for European reasons." Apparently he hoped for a seizure of power by the Austrian National Socialists without outside help, as he had also succeeded in doing.

From Berlin, therefore, the National Socialist underground movement in Austria was encouraged, and since the July Agreement its influence grew. Chancellor Schuschnigg's efforts to obtain a British declaration of guarantee failed in the early summer of 1937. The German ambassador in Vienna, Franz von Papen, advised him to meet with Hitler in early February 1938, to which Schuschnigg agreed after some hesitation. With Seyß-Inquart he worked out a series of concessions to present to Hitler. Without Schuschnigg's knowledge, Seyß-Inquart played the planned concessions to Hitler.

On the morning of February 12, 1938, Schuschnigg arrived at the Berghof in Bavaria. Hitler received him on the stairs of the Berghof and led him into his study. After briefly commenting on Schuschnigg's reference to the beautiful view, he abruptly turned to Austrian politics: Austria's history, he said, was one of uninterrupted treason against the people. This historical absurdity must finally come to an end. He, Hitler, was determined to put an end to it all, his patience was exhausted. Austria stood alone, neither France nor Great Britain nor Italy would lift a finger to save it. Schuschnigg had only until the afternoon. At lunch Hitler showed himself to be an attentive host, but the three generals who were to command a possible operation against Austria were also at the table. Ribbentrop and Papen presented Schuschnigg that afternoon with a document containing demands that went well beyond Schuschnigg's planned concessions. Hitler threatened to march in the Wehrmacht if Schuschnigg did not sign the list of demands. Demands included the lifting of the party ban on the Austrian National Socialists and their full freedom of agitation, increased involvement in the government, and that Seyß-Inquart become Minister of the Interior, Glaise-Horstenau Minister of War, and Hans Fischböck Minister of Finance. Hitler refused to negotiate any change in the text. When Schuschnigg stated that he was willing to sign but could not guarantee ratification, Hitler summoned General Keitel. Hitler now agreed to give the Austrians three days to sign the document. Schuschnigg signed and declined Hitler's invitation to a souper. Accompanied by Papen, he drove to the frontier and reached Austria again at Salzburg. Schuschnigg bowed to the threats and believed he could secure Austria's independence with the Berchtesgaden Agreement. As demanded by Hitler, Seyß-Inquart was appointed Minister of the Interior on 16 February, thus gaining control of the Austrian police.

Hitler, too, was initially satisfied with the result: According to historian Henning Köhler, he had only allowed the crisis to escalate for domestic political reasons, in order to distract attention from the Blomberg-Fritsch crisis, and had achieved a better result than expected.

The Berchtesgaden Agreement led to protest strikes in Viennese factories on 14 February 1938. On 16 February, shop stewards from these factories requested a personal meeting with Schuschnigg to explain the workers' readiness to fight for a free Austria. Schuschnigg did not respond until March 4. Subsequently, on March 7, a shop stewards' conference was held in the Social Democratic workers' home in Floridsdorf; the only meeting of its kind that did not have to be held in a conspiratorial manner because of the party ban on the SDAPÖ. However, the government did not respond to the demand for elections in the trade union federation set up by the dictatorship.

For the referendum announced by Schuschnigg, 200,000 leaflets were printed by the Revolutionary Socialists, which were burned after the vote was cancelled.

Hitler's ultimatum

Military preparations against Austria kept up the pressure.

Asked by Göring for a statement, the British Ambassador Nevile Henderson declared to Hitler on 3 March 1938, in the spirit of the appeasement policy, that Great Britain considered Germany's claims against Austria to be justified in principle. The Austrian National Socialists received a great boost from the Berchtesgaden events.

Schuschnigg realized that within a few weeks his new government partners were pulling the rug out from under him and were about to seize power. On February 24, 1938, in a public speech, he invoked Austria's independence: "To the death! Red-White-Red! Austria!"

The content and tone of Schuschnigg's speech caused Hitler initial irritation, which increased when Schuschnigg announced on March 9 that he intended to hold a referendum on Austrian independence as early as the following Sunday, March 13.

The question was to be whether or not the people wanted a "free and German, independent and social, a Christian and united Austria". Schuschnigg refrained from asking the cabinet about this, as was required by the constitution on the occasion of a referendum. The votes were to be counted by the Vaterländische Front alone. The members of the Civil Service were to go to the polls the day before the election in their departments in unison under supervision and openly hand over their completed ballot papers to their superiors. In addition, only ballot papers with the imprint "YES" were to be issued in the polling stations, which would have meant a "Yes" to independence. Minister of the Interior Seyß-Inquart and Minister Glaise-Horstenau immediately explained to their Chancellor that the vote in this form was unconstitutional.

Whether the plebiscite was a "flight to the front" by the Austrian chancellor or a "serious mistake," Hitler again changed his strategy and now set about achieving his goal immediately: He ordered the mobilization of the 8th Army scheduled for the invasion and on 10 March instructed Seyß-Inquart to issue an ultimatum and mobilize the Austrian partisans. The Reich government demanded that the referendum be postponed or cancelled. Joseph Goebbels noted in his diary:

"Still conferring with the Führer alone until 5h in the morning. He believes the hour has come. Just wants to sleep on it. Italy and England will do nothing. Maybe France, but probably not. Risk not as great as Rhineland occupation."

The following day, March 11, 1938, Hermann Göring took charge of the preparations for the "Anschluss" of Austria by telephone and telegraph. He ultimatively demanded Schuschnigg's resignation and the appointment of Seyß-Inquart as Chancellor. Glaise-Horstenau, who had been in Berlin, delivered Hitler's ultimatum from there, which was additionally reinforced by Göring in telephone conversations with Seyß-Inquart and Schuschnigg. Following instructions from Berlin, the Austrian National Socialists poured into the Federal Chancellery and occupied stairways, corridors and offices. On the afternoon of March 11, Schuschnigg agreed to cancel the referendum. That evening Hitler forced his resignation in favor of Seyß-Inquart (Federal President Wilhelm Miklas had previously tried in vain to persuade several non-National Socialists to assume the chancellorship).

Schuschnigg declared his resignation on the radio ("God save Austria!") and instructed the Austrian army to withdraw without opposition if German troops invaded.

At the same time, the takeover of power by Austrian National Socialists began in Vienna and all the provincial capitals, and they hoisted swastika flags on numerous public buildings on the evening of March 11, long before the invasion of the German Wehrmacht began. The Federal Chancellery in Vienna, where Federal President Miklas was also in office, was surrounded by armed men - allegedly for his protection. On 12 March 1938, in many places, appointed Nazi officials officiated during the night of 11 to 12 March.

Consequently, with Hitler's consent, Göring had a telegram drafted requesting the dispatch of troops from the Reich, which the Reich government then sent to itself in the name of the new Chancellor Seyß-Inquart. The latter was only informed of the "urgent request" of the "provisional Austrian government" after the fact.

Controversy surrounding the decision-making process

How the decision-making process within the National Socialist polycracy actually took place in March 1938 is a matter of dispute among researchers:

Göring's biographer Alfred Kube believes that it was primarily due to Göring's initiative that Schuschnigg's plan for a plebiscite was not only thwarted, but that the entire neighboring country was annexed. Hitler had initially been rather hesitant about this. This thesis, which goes back to Göring's statements in the Nuremberg trial against the main war criminals, is shared by a large part of historians.

The Heidelberg historian Georg Christoph Berger Waldenegg contradicts this: according to his analysis, Hitler did not have to be "pushed to his happiness": After Schuschnigg's provocative plebiscite proposal, he was so enraged that, as Ambassador Henderson learned, the moderates in the Reich's leadership could no longer have held him back.

According to Henning Köhler, the initiative for the Anschluss also lay with Hitler. He interprets the Anschluss crisis functionally as an indication of the erratic character of Nazi foreign policy, which did not proceed according to a predefined programme, but improvised on a case-by-case basis and pragmatically seized opportunities as they arose.

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Anschluss?

A: The Anschluss was the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938.

Q: What happened to Austria-Hungary and the German Empire after the First World War?

A: Both Austria-Hungary and the German Empire were abolished after the First World War.

Q: What did many hope for after the First World War?

A: Many hoped for the unification of the Republic of German Austria with the German Republic into a Greater Germany that would include all Germans.

Q: Why was the unification of the Republic of German Austria with the German Republic forbidden?

A: The unification of the Republic of German Austria with the German Republic was forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles without the permission of the League of Nations.

Q: What did all of the major Allies need to agree on to make such a decision?

A: All of the major Allies needed to agree to make the decision to unify the Republic of German Austria with the German Republic into a Greater Germany.

Q: When was the Anschluss?

A: The Anschluss was in 1938.

Q: Which country annexed Austria during the Anschluss?

A: Nazi Germany annexed Austria during the Anschluss.

Search within the encyclopedia