Homo

![]()

This article explains the biological generic name of humans; for other meanings, see Homo (disambiguation).

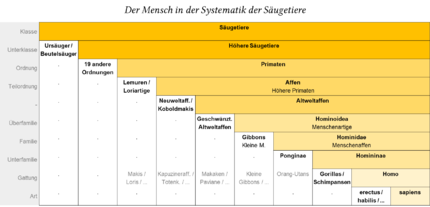

Homo (Latin hŏmō [ˈhɔmoː] "man", "man") is a genus of great apes (Hominidae) in the mammalian class, which includes anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) and their closest extinct relatives. Accurate delineation of the genus Homo from related genera within the Hominini is difficult. The use of worked stone tools (scree tools) is often cited as a criterion.

An important common feature (synapomorphy) of all species of the genus Homo is the number of cusps (tubercles) on the posterior molars: Homo have six or seven cusps, Australopithecines had fewer.

Features

→ Main article: Hominization and phylogeny of humans

| Taxon | Body weight (in kg) | |

| males | female | |

| Chimpanzees | 60–90 | 30–47 |

| Australopithecus afarensis | 45 | 29 |

| Australopithecus africanus | 41 | 30 |

| Homo rudolfensis | 60 | 51 |

| Homo habilis | 37 | 32 |

| Homo naledi | 40–55 | |

| homo ergaster | 68 | 54 |

| Homo erectus | 59 | 57 |

| Homo heidelbergensis | 84 | 78 |

| Neanderthal | 76 | 65 |

| Homo sapiens | 68 | 57 |

To date, there is no precise benchmark against which the potential assignment of newly discovered fossils to the genus Homo could be measured: Type species of the genus is Homo sapiens, but what criteria could be used to justify the clear morphological distance of Homo sapiens and the genus Homo from a related genus has never been established. Thus, in 1964, in the first description of Homo habilis, the definition of the genus could be unceremoniously changed by lowering the lower limit of brain volume for species of the genus Homo to 600 cm³ so that the fossils assigned to the new species could still be placed in the genus Homo. At the same time, some other criteria for assigning fossils to the genus Homo were given, including: the construction of the pelvis and legs are adapted to a habitually erect posture and to an upright gait; the arms are shorter than the legs; the thumb is well developed and fully opposable; the hand is capable of both power grip and precision grip.

According to Bernard Wood and Mark Collard, the assignment of species to the genus Homo has often been made by other authors based on four criteria:

- The cranial internal volume - the brain size - of at least 600 cm³,

- the assumed ability to speak, derived from cranial effusions, on the basis of which Broca's area and Wernicke's centre were found to be well developed,

- the evidence of tool use and

- the opposable thumb and the precision grip of the hand.

Wood and Collard explain that it is easy to understand that these criteria can only be inadequately deduced from many of the fossils found. In addition, without precise knowledge of body size, the relationship between brain size and behaviour remains just as unclear as the relationship between the developing ability to speak and certain features of the cerebral surface; whether Homo rudolfensis used tools is as yet unproven, but there are indications that representatives of the genus Australopithecus also used tools; and the features of the hand mentioned are by no means a unique feature of the genus Homo, but have also been found in species of other genera.

Wood and Collard therefore argued that instead of emphasizing individual features, the assignment of a species to the genus Homo must demonstrate that this species resembles the type species Homo sapiens more closely than the type species of Ardipithecus, Australopithecus, Kenyapithecus and Paranthropus. In particular, it had to be proven that the body structure (especially the masticatory apparatus), the physical development, and the manner of locomotion were closer to the type specimen of the genus than to the older genera of the Hominini. Using these standards, Wood and Collard concluded that Homo habilis and Homo rudolfensis show greater similarities to Australopithecus and Paranthropus than to Homo and should therefore be assigned to the genus Australopithecus; Homo erectus, Homo ergaster, Homo heidelbergensis and Homo neanderthalensis, on the other hand, show sufficient morphological proximity to Homo sapiens according to Wood and Collard.

Tim White pointed out in 2003 that the dentition and skeleton of modern humans show considerable variability; therefore, before delineating additional species, it should always be considered that the ancestors of humans may also have exhibited similar variability.

Precision grip (opposed thumb - here against middle and index finger)

Historical

The genus Homo was introduced in 1758 by Carl von Linné in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae. Two recent species were assigned to this genus: on the one hand Homo sylvestris - occurring on Java, nocturnal and colloquially called "orang outang"; on the other hand Homo sapiens - diurnal and divided into six groups. Two of these groups - characterized as "wild" and "monstrous" respectively - are not biological entities according to current knowledge; the other four groups correlate with the four geographical regions known to Linné: Africa, America, Asia and Europe.

The first attempt to distinguish the genus Homo from other mammals on the basis of anatomical characteristics was made in 1775 by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in his dissertation De generis humani varietate nativa ("On the natural differences in the human race").

The first fossil species of the genus Homo was named in 1864 by the Irish geologist William King: Homo neanderthalensis; King had already used the name "Homo Neanderthalensis King" a year earlier in a lecture to the Geology Section of the British Association for the Advancement of Sciences after discussing the skull shape of the Neandertal 1 fossil and its divergences from modern humans. This was followed in 1899 by the species Homo spelaeus ("cave man") proposed by Georges Vacher de Lapouge, to which the Cro-Magnon 1 fossil was assigned as the type specimen; all fossils of this age class ("Cro-Magnon men") are now counted as Homo sapiens. The third fossil Homo species was named in 1908, after Otto Schoetensack decided to name Mauer's mandible, correctly identified as "preneandertaloid", as Homo heidelbergensis.

The inclusion of Mauer's extremely massive, "primitive" mandible, compared to Homo sapiens, Homo spelaeus, and even Homo neanderthalensis, in the genus Homo greatly increased its morphological range of variation. This development continued when Arthur Smith Woodward named the species Homo rhodesiensis in 1921 and the Dutch researcher Willem Oppennoorth named Homo soloensis in 1932.

The fossils of Homo soloensis ("Man from the Solo River" on Java) are today placed with Homo erectus: a taxon to which, from 1950 onwards, on the suggestion of Ernst Mayr - in consensus with the leading palaeoanthropologists of the time - numerous other fossils from various sites were assigned, initially with their own species name. However, this had the effect of further increasing the range of variation in Homo morphology: for example, by Atlanthropus mauritanicus, Pithecanthropus erectus, Sinanthropus pekinensis, and Telanthropus capensis (now separated again by some paleoanthropologists and referred to as Homo ergaster). However, the common feature of all fossils attributed to Homo initially remained the minimum volume of 900 cubic centimetres for the inner volume of the skull, as defined by Mayr in 1950, as well as a posture and mode of locomotion characterised by an upright gait.

However, this consensus was abandoned by Louis Leakey et al. in 1964, when Homo habilis was first described: Members of this very early Homo species walked upright at least some of the time, but had a brain volume of only about 600 to 700 cm³. Now 600 cm³ was considered the lower limit, and the already imprecise definition of the genus Homo became even more "nebulous".

Finally, in addition to Homo habilis, another early species of the genus Homo was placed, called Homo rudolfensis. Its delimitation from Homo habilis has been incomplete so far, because hardly any skeletal bones from below the head could be assigned to Homo rudolfensis without doubt. Distinguishing features are, for example, the teeth of Homo rudolfensis, which are larger than those of the later Homo species, the larger internal cranial volume of at least 750 cm³ compared to Homo habilis, and the broader face formed from thicker bones compared to Homo habilis.

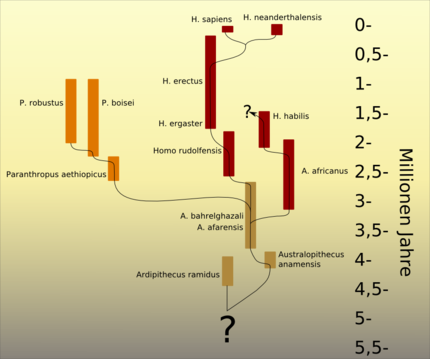

Hypothesis on the relationship of the Australopithecus and Homo species, as advocated by Friedemann Schrenk, for example, on the basis of current findings.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is Homo?

A: Homo is a genus of primates that walk on two legs and includes the only living species, Homo sapiens (humans).

Q: When did the Homo genus begin?

A: The Homo genus began approximately 2.3 million years ago.

Q: What were the ancestors of Homo?

A: The ancestors of Homo were likely some line of Australopithecine apes.

Q: What characteristics do species of Homo have?

A: Species of Homo have a larger brain (above 900ml), improved walking and running ability, a more vertical forehead, a rounder skull, smaller teeth, shorter arms, longer legs, and a more delicate skeleton, particularly in our species.

Q: Did all species of Homo use stone tools?

A: Yes, all species of Homo used stone tools.

Q: Is there evidence of when language developed among species of Homo?

A: There is no evidence of when language developed among species of Homo.

Q: Is human evolution a widely studied topic?

A: Yes, human evolution is a much-studied topic.

Search within the encyclopedia