Holy Roman Empire

![]()

This article is about the Holy Roman Empire (German Nation) of the Middle Ages and early modern times. For the ancient Roman Empire, see Roman Empire.

Holy Roman Empire (Latin Sacrum Imperium Romanum or Sacrum Romanum Imperium) was the official name for the domain of the Roman-German emperors from the late Middle Ages to 1806. The name of the empire derived from the claim of the medieval Roman-German rulers to continue the tradition of the ancient Roman Empire and to legitimize their rule as God's holy will in the Christian sense.

The empire was formed in the 10th century under the Ottonian dynasty from the former Carolingian East Frankish Empire. With the imperial coronation of Otto I in Rome on 2 February 962, the Roman-German rulers (like the Carolingians before them) took up the idea of the renewed Roman Empire, which was held to at least in principle until the end of the empire. The territory of the East Frankish Empire was first referred to in sources in the 11th century as Regnum Teutonicum or Regnum Teutonicorum ("Kingdom of the Germans"); however, this was not the official imperial title. The name Sacrum Imperium is first documented for 1157 and the title Sacrum Romanum Imperium for 1184 (older research assumed 1254). The addition of the German nation (Latin Nationis Germanicæ) was occasionally used from the late 15th century onwards. Due to its pre- and supranational character of a multi-ethnic empire with universal claims, the empire never developed into a nation-state or a state of the modern type, but remained a monarchically led, estates-based entity consisting of emperor and imperial estates with only a few common imperial institutions.

In contrast to the German Empire, founded in 1871, it is also called the Roman-German Empire or the Old Empire.

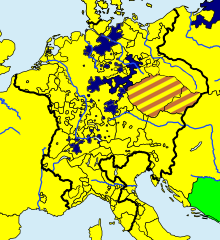

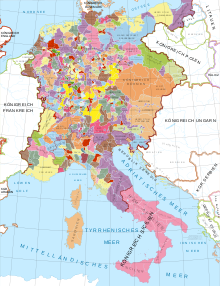

The extent and borders of the Holy Roman Empire changed considerably over the centuries. At its greatest extent, the empire encompassed almost the entire territory of what is now central and parts of southern Europe. Since the early 11th century it consisted of three empire parts: The Northern Alpine (German) part of the empire, Imperial Italy, and-until its de facto loss in the late Middle Ages-Burgundy (also known as Arelat).

Since the early modern period, the empire was structurally no longer capable of offensive warfare, expansion of power and expansion. Since then, the protection of law and the preservation of peace were seen as its essential purposes. The empire was supposed to ensure peace, stability and the peaceful resolution of conflicts by containing the dynamics of power: it was supposed to protect subjects from the arbitrariness of sovereigns and smaller imperial estates from violations of the law by more powerful estates and the emperor. Since the Peace of Westphalia of 1648, neighbouring states were also integrated into its constitutional order as imperial estates, the empire also fulfilled a peacekeeping function in the system of European powers.

From the middle of the 18th century, the empire was less and less able to protect its members against the expansionist policies of internal and external powers. This contributed significantly to its downfall. The Napoleonic Wars and the resulting formation of the Confederation of the Rhine, whose members withdrew from the Empire, had rendered it virtually incapable of action. The Holy Roman Empire ceased to exist on August 6, 1806, when Emperor Francis II laid down the imperial crown.

Emperor and Empire on an engraving by Abraham Aubry, Nuremberg 1663/64. In the centre Emperor Ferdinand III is depicted as the head of the Empire in a circle of electors. At his feet sits a female figure as an allegory of the empire, recognisable by the insignia of the imperial orb. The fruits surrounding her symbolise the hope of new prosperity after the end of the Thirty Years' War. In the original, the depiction is signed with: Teutschlands fröhliches zuruffen / zu glückseliger Fortsetztung / der mit Gott / in regensburg angestellten allgemeine Versammlung des H. Röm. Reiches obersten Haubtes und Gliedern

Character

The Holy Roman Empire emerged from the East Frankish Empire. It was a pre-national and supranational entity, a feudal empire and a confederation of persons, which never developed into a nation-state such as France or Great Britain and, for reasons of the history of ideas, never wanted to be understood as such. The competing opposition of consciousness in the tribal duchies or, later, in the territories and the supranational consciousness of unity was never fought out or resolved in the Holy Roman Empire; an overarching national feeling did not develop.

The history of the empire was marked by disputes about its character, which - since the balance of power within the empire was by no means static - changed again and again in the course of the centuries. From the 12th and 13th centuries onwards, a reflection on the political polity can be observed that is increasingly oriented towards abstract categories. With the emergence of universities and an increasing number of trained jurists, the categories of monarchy and aristocracy, which had been taken over from the ancient doctrine of forms of state, were opposed to each other for several centuries. However, the empire could never be clearly assigned to one of the two categories, since the power to govern the empire was neither in the hands of the emperor alone, nor in the hands of the electors alone, nor in the hands of the entirety of an association of persons such as the Reichstag. Rather, the empire combined features of both forms of government. Thus, in the 17th century, Samuel Pufendorf concluded in his De statu imperii, published under a pseudonym, that the empire was of its own kind - an "irregulare aliquod corpus et monstro simile" (irregulare aliquod corpus et monstro simile), which Karl Otmar von Aretin describes as the most frequently quoted sentence about the imperial constitution from 1648 onwards.

As early as the 16th century, the concept of sovereignty became increasingly central. However, the distinction based on this between a federal state (in which sovereignty lies with the state as a whole) and a confederation of states (which is a federation of sovereign states) is an ahistorical approach, since the fixed meaning of these categories only emerged later. Nor is it informative with regard to the empire, since the empire again could not be assigned to either category: just as the emperor never succeeded in breaking the regional self-will of the territories, so it did not disintegrate into a loose confederation of states. In more recent research, the role of rituals and the staging of rule in pre-modern society, and specifically with regard to the unwritten order of rank and constitution of the empire until its dissolution in 1806, has been increasingly emphasized (symbolic communication).

As an "umbrella organization", the empire overarched many territories and provided the coexistence of the various sovereigns with framework conditions prescribed by imperial law. These quasi-autonomous but not sovereign principalities and duchies recognized the emperor as at least the ideal head of the empire and were subject to the imperial laws, the imperial jurisdiction and the resolutions of the imperial diet, but at the same time also participated in imperial politics through the election of kings, electoral capitulation, imperial diets and other estates' representations and could influence these for themselves. In contrast to other countries, the inhabitants were not directly subject to the emperor, but to the sovereign of the respective imperial territory. In the case of the imperial cities, this was the magistrate of the city.

Voltaire described the discrepancy between the name of the empire and its ethno-political reality in its late phase (since the early modern period) by saying: "This corpus, which still calls itself the Holy Roman Empire, is in no sense sacred, nor Roman, nor an empire." Montesquieu, in his 1748 work On the Spirit of Laws, described the Empire as a "république fédérative d'Allemagne," a federally constituted commonwealth of Germany.

In more recent research, the positive aspects of the empire are once again being emphasized more strongly. Not only did it provide a functioning framework of political order for several centuries, but it also (precisely because of its rather federal structure of rule) allowed for a variety of developments in the various dominions.

History

Origin

After Charlemagne's death in 814, the Frankish Empire had undergone several divisions and reunions of the parts of the empire among his grandsons. Such divisions among the sons of a ruler were normal under Frankish law and did not mean that the unity of the empire ceased to exist, since a common policy of the parts of the empire and a future reunification were still possible. If one of the heirs died childless, his part of the empire fell to one of his brothers or was divided among them.

Such a division was also decided in the Treaty of Verdun in 843 among the grandsons of Charles. The empire was divided between Charles the Bald, who received the western part (Neustria, Aquitaine) up to about the Meuse, Lothar I - who took over the imperial dignity in addition to a central strip (with a large part of Austrasia and the formerly Burgundian and Lombard territories up to about Rome) - and Louis the German, who received the eastern part of the empire with a part of Austrasia and the conquered Germanic realms north of the Alps.

Although the future map of Europe is discernible here, unintended by the parties involved, further, mostly warlike reunions and divisions between the sub-kingdoms occurred in the course of the next fifty years. Only when Charles the Fat was deposed in 887 because of his failure in the defensive struggle against the plundering and robbing Normans was a new head of all parts of the empire no longer appointed, but the remaining sub-kingdoms elected their own kings, some of whom no longer belonged to the dynasty of the Carolingians. This was a clear sign of the drifting apart of the parts of the empire and the reputation of the Carolingian dynasty, which had reached its lowest point, plunged the empire into civil wars due to disputes over the throne and was no longer able to protect it in its entirety against external threats. As a result of the now missing dynastic bracket, the empire disintegrated into numerous small counties, duchies and other regional dominions, most of which only formally recognized the regional kings as sovereigns.

Particularly clearly, in 888 the central part of the empire disintegrated into several independent petty kingdoms, including High and Low Burgundy and Italy (while Lorraine was annexed to the Eastern Empire as a sub-kingdom), whose kings had prevailed against Carolingian pretenders with the support of local nobles. In the Eastern Kingdom, local nobles elected dukes at tribal level. After the death of Louis the Child, the last Carolingian on the East Frankish throne, the Eastern Kingdom could also have disintegrated into petty kingdoms if this process had not been halted by the joint election of Conrad I as East Frankish king. Although Conrad did not belong to the dynasty of the Carolingians, he was a Frank from the dynasty of the Conradines. However, Lorraine joined the West Frankish Empire on this occasion. In 919, with the Saxon Duke Henry I, a non-Frank was elected king of the East Frankish Empire for the first time in Fritzlar. From this point on, the empire was no longer carried by a single dynasty, but the regional greats, nobles and dukes decided on the ruler.

In 921, in the Treaty of Bonn, the West Frankish ruler recognized Henry I as an equal, and he was allowed to use the title rex francorum orientalium, King of the Eastern Franks. The development of the empire as a permanently independent and viable state was thus essentially completed. In 925, Henry succeeded in reincorporating Lorraine into the East Frankish Empire.

Despite the detachment from the overall empire and the unification of the Germanic peoples who, in contrast to the common people of West Franconia, did not speak Romanized Latin, but theodiscus or diutisk (from diot volksmäßig, volksprachig), this empire was not an early "German nation-state". A superior "national" sense of belonging together did not exist in East Franconia anyway, imperial and linguistic community were not identical. Just as little was it already the later Holy Roman Empire.

The growing self-confidence of the new East Frankish royal dynasty was already evident in the accession of OttoI. , son of Henry I, who was crowned on the supposed throne of Charlemagne in Aachen. Here the increasingly sacred character of his reign was shown by the fact that he had himself anointed and pledged his protection to the church. After several battles against kinsmen and Lorraine dukes, he succeeded in confirming and consolidating his rule by defeating the Hungarians in 955 on the Lechfeld near Augsburg. Still on the battlefield, the army is said to have saluted him as emperor, according to Widukind of Corvey.

This victory over the Hungarians prompted Pope John XII to summon Otto to Rome and offer him the imperial crown to act as protector of the Church. John was at this time under the threat of regional Italian kings and hoped for help from Otto against them. But the pope's call for help also proclaims that the former barbarians had been transformed into the bearers of Roman culture and that the eastern regnum was seen as the legitimate successor to Charlemagne's emperorship. Otto answered the call and moved to Rome. There he was crowned emperor on February 2, 962. West and East Franconia now finally developed politically into separate realms.

Medieval

See also: Germany in the Middle Ages

Ottonian rule

Compared to the High and Late Middle Ages, the empire in the Early Middle Ages was still little differentiated in terms of estates and society. It became visible in the army formation, in the local court assemblies and in the counties, the local administrative units already installed by the Franks. The highest representative of the political order of the empire, responsible for the protection of the empire and the peace within, was the king. The duchies served as political subunits. Until the late Middle Ages, consensus between the ruler and the great powers of the empire was important (consensual rule).

Although in the early Carolingian period around 750 the Frankish official dukes had been deposed for the peoples subjugated by the Franks or first created by their territorial amalgamation, five new duchies arose in the East Frankish Empire between 880 and 925, favoured by the external threat and the preserved tribal law: that of the Saxons, the Bavarians, the Alemanni, the Franks and the Duchy of Lorraine, newly created after the division of the Empire, to which the Frisians also belonged. However, already in the 10th century, there were serious changes in the structure of the duchies: Lorraine was divided into Lower and Upper Lorraine in 959 and Carinthia became an independent duchy in 976.

Since the empire had come into being as an instrument of the self-confident duchies, it was no longer divided between the sons of the ruler and, moreover, remained an elective monarchy. The non-division of the "inheritance" between the sons of the king was admittedly contrary to traditional Frankish law. On the other hand, the kings ruled the tribal dukes only as feudal lords, and the direct influence of the royalty was accordingly small. In 929, Henry I stipulated in his "House Rules" that only one son should succeed to the throne. Already here the idea of succession, which characterized the empire until the end of the Salian dynasty, and the principle of elective monarchy are linked.

Otto I (r. 936-973) succeeded, as a result of several campaigns to Italy, in conquering the northern part of the peninsula and integrating the kingdom of the Lombards into the empire. However, a complete integration of imperial Italy with its superior economic power never really succeeded in the following period. Moreover, the necessary presence in the south sometimes tied up quite considerable forces. Otto's coronation as emperor in Rome in 962 linked the later Roman-German kings' claim to the western imperial dignity for the rest of the Middle Ages. The Ottonians now exercised a hegemonic position of power in Latin Europe.

Under Otto II, the last remaining ties to the West Frankish-French Empire, which still existed in the form of kinship relations, were also severed when he made his cousin Charles Duke of Lower Lotharingia. Charles was a descendant of the Carolingian dynasty and at the same time the younger brother of the West Frankish king Lothar. However, it was not - as later research claimed - a "faithless Frenchman" who became a liegeman of a "German" king. Such categories of thought were still unknown at that time, especially since the leading Frankish-Germanic stratum of the West Frankish Empire continued to speak its Old German dialect for some time after the partition. In more recent research, the Ottonian period is also no longer understood as the beginning of "German history" in the narrow sense; this process extended into the 11th century. In any case, Otto II played one cousin off against the other to gain an advantage for himself by driving a wedge into the Carolingian family. Lothar's reaction was fierce, and both sides emotionally charged the dispute. However, the consequences of this final rift between the successors of the Frankish Empire became apparent later. The French kingship, however, was now seen as independent of the emperor due to the emerging French self-confidence.

The integration of the church into the secular system of rule of the empire, which began under the first three Ottonians and was later referred to by historians as the "Ottonian-Salian imperial church system", reached its climax under Henry II. The imperial church system formed one of the defining elements of the empire's constitution until its end; however, the involvement of the church in politics was not in itself exceptional; the same can be observed in most early medieval empires of Latin Europe. Henry II demanded unconditional obedience from the clergy and the immediate implementation of his will. He completed the royal sovereignty over the imperial church and became a "monk-king" like hardly any other ruler of the empire. But he not only ruled the church, he also ruled the empire through the church by filling important offices - such as that of chancellor - with bishops. Secular and ecclesiastical matters were basically not distinguished and were equally negotiated in synods. However, this did not only result from the endeavour to counterbalance the duchies' urge for greater independence, which stemmed from Frankish-Germanic tradition, with a counterweight loyal to the king. Rather, Henry saw the realm as the "house of God", which he had to care for as God's steward. At the latest now the realm was "holy".

High Middle Ages

As the third important part of the empire, the kingdom of Burgundy joined the empire under Conrad II, even though this development had already begun under Henry II: since the Burgundian king Rudolf III had no descendants, he named his nephew Henry as his successor and placed himself under the protection of the empire. In 1018 he even handed over his crown and sceptre to Henry.

Conrad's reign was further characterized by the developing notion that the realm and its rule existed independently of the ruler and developed legal force. This is evidenced by Conrad's "ship metaphor" handed down by Wipo (see the corresponding section in the article on Conrad II) and by his claim to Burgundy - for actually Henry was to inherit Burgundy and not the realm. Under Conrad also began the emergence of the ministerials as a separate class of the lower nobility, by granting fiefs to the king's unfree servants. Important for the development of law in the empire were his attempts to push back the so-called judgments of God as a legal remedy in the northern part of the empire by applying Roman law, to which these judgments were unknown.

Conrad continued the imperial church policy of his predecessor, but not with the same vehemence. He judged the church more according to what it could do for the empire. For the most part, he appointed bishops and abbots with great intelligence and spirituality. However, the Pope did not play a major role in his appointments either. All in all, his reign appears to be a great "success story", which is probably also due to the fact that he ruled at a time when there was generally a kind of spirit of optimism, which led to the Cluniac reform at the end of the 11th century.

Henry III took over a consolidated empire from his father Conrad in 1039 and, unlike his two predecessors, did not have to fight for his power. Despite warlike actions in Poland and Hungary, he attached great importance to keeping the peace within the empire. This idea of a general peace, a peace with God, originated in southern France and had spread throughout the Christian West since the middle of the 11th century. It was intended to curb feuding and blood feuds, which had increasingly become a burden on the functioning of the empire. The initiator of this movement was the Cluniac monasticism. At least on the highest Christian holidays and on the days sanctified by the Passion of Christ, i.e. from Wednesday evening to Monday morning, weapons were to remain silent and the "peace of God" was to prevail.

Henry had to accept a hitherto completely unknown condition for the consent of the great men of the realm in the election of his son, the later Henry IV, as king in 1053. Subordination to the new king was only to apply if Henry IV proved to be a right ruler. Even though the power of the emperors over the Church was at one of its high points with Henry III - it had been he who decided on the occupation of the sacred throne in Rome - the balance of his reign is mostly seen negatively in recent research. Thus Hungary emancipated itself from the empire, which had previously still been an imperial fiefdom, and several conspiracies against the emperor showed the unwillingness of the great of the empire to submit to a strong kingship.

Due to the early death of Henry III, his six-year-old son Henry IV came to the throne. His mother Agnes took over his guardianship until he was 15 years old in 1065. This led to a gradual loss of power and importance of the kingship. Through the "coup d'état of Kaiserswerth" a group of imperial princes under the leadership of the Archbishop of Cologne Anno II was able to temporarily seize the power of government. In Rome, the opinion of the future emperor was of no interest to anyone at the next papal election. The annalist of the Niederaltaich monastery summarized the situation as follows:

"[...] those present at court, however, each cared for himself as much as he could, and no one instructed the king in what was good and just, so that many things in the kingdom became disordered."

The so-called Investiture Controversy became decisive for the future position of the Imperial Church. It was a matter of course for the Roman-German rulers to fill the vacant bishoprics in the empire. Due to the weakness of the kingship during the reign of Henry's mother, the Pope, as well as ecclesiastical and secular princes, had attempted to seize royal possessions and rights. Later attempts to reassert royal power were, of course, met with little sympathy. When Henry attempted to impose his candidate for the bishopric of Milan in June 1075, Pope Gregory VII reacted immediately. In December 1075, Gregory banished King Henry, thus releasing all his subjects from their oath of allegiance. The princes of the realm demanded that Henry have the ban lifted by February 1077, otherwise he would no longer be recognized by them. In the other case the Pope would be invited to decide the dispute. Henry IV had to submit and humbled himself in the legendary walk to Canossa. The positions of power had turned into their opposite; in 1046 Henry III had still judged three popes, now one pope was to judge the king.

Henry IV's son, with the help of the Pope, revolted against his father and forced his abdication in 1105. The new king Henry V ruled until 1111 in consensus with the ecclesiastical and secular greats. The close alliance between ruler and bishops could also be continued against the pope in the investiture question. The solution found by the pope was simple and radical. In order to guarantee the separation of the spiritual duties of the bishops from the secular duties hitherto performed, as demanded by the church reformers, the bishops were to return the rights and privileges they had received from the emperor or king in the previous centuries. On the one hand, this meant that the bishops' duties towards the empire ceased, and on the other hand, the king's right to influence the appointment of the bishops. However, since the bishops did not want to give up their secular regalia, Henry imprisoned the Pope and extorted the right of investiture as well as his imperial coronation. It was not until 1122, in the Concordat of Worms, that the princes forced a settlement between Henry and the reigning Pope Calixt II. Henry had to renounce the right of investiture with the spiritual symbols of ring and staff (per anulum et baculum). The emperor was allowed to be present at the election of bishops and abbots. The conferral of royal rights (regalia) on the newly elected was only allowed by the emperor with the sceptre. Since then the princes have been regarded as "the heads of state". It was no longer the king alone but also the princes who represented the empire.

After the death of Henry V in 1125, Lothar III was elected king, prevailing in the election against the Swabian Duke Frederick II, the closest relative of the emperor who died childless. It was no longer hereditary legitimacy that determined the succession to the throne in the Roman-German Empire, but the election of the princes was decisive. In 1138 the Staufer Conrad was elevated to king. However, Conrad's wish to acquire the imperial crown was not to be fulfilled. Also his participation in the Second Crusade was not successful, he had to turn back in Asia Minor. Instead, he succeeded in forming an alliance with the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos against the Normans.

In 1152, after the death of Conrad, his nephew Frederick, Duke of Swabia, was elected king. Frederick, called "Barbarossa", pursued a single-minded policy aimed at regaining imperial rights in Italy (see honor imperii), for which Frederick undertook a total of six campaigns in Italy. In 1155 he was crowned emperor, but due to a campaign against the Norman Empire in lower Italy, which had not taken place but had been guaranteed by treaty, tensions arose with the papacy, and relations with Byzantium also deteriorated. The upper Italian city-states, especially the rich and powerful Milan, also resisted Frederick's attempts to strengthen the imperial administration in Italy (see Diet of Roncaglia). It eventually came to the formation of the so-called Lombard League, which was quite able to hold its own militarily against the Staufer. At the same time, a disputed election of a pope had taken place, whereby Pope Alexander III, who had been elected with the majority of the votes, was at first not recognized by Frederick. Only after it became clear that a military solution had no chance of success (in 1167 a plague had raged in the imperial army outside Rome, in 1176 defeat in the Battle of Legnano), did an agreement between emperor and pope finally come about in the Peace of Venice in 1177. The upper Italian cities and the emperor also came to an agreement, although Frederick was far from being able to realize all of his goals.

In the empire, the emperor had fallen out with his cousin Henry, the Duke of Saxony and Bavaria from the House of Guelph, after the two had worked closely together for over two decades. However, when Heinrich now attached conditions to his participation in a campaign in Italy, the overpowering Duke Heinrich was overthrown by Frederick at the instigation of the princes. In 1180, Henry was put on trial and the Duchy of Saxony was broken up and Bavaria was reduced in size, although it was not so much the Emperor who profited from this as the territorial lords in the Empire.

The emperor died in June 1190 in Asia Minor during a crusade. He was succeeded by his second eldest son Henry VI. He had already been elevated to Caesar by his father in 1186 and was since then considered the designated successor of Frederick. In 1191, the year of his coronation as emperor, Henry tried to take possession of the Norman kingdom in Lower Italy and Sicily. Since he was married to a Norman princess and the ruling house of Hauteville had died out in the main line, he was also able to assert claims, which, however, could not be enforced militarily at first. It was not until 1194 that he succeeded in conquering Lower Italy, where Henry proceeded against oppositional forces with sometimes extreme brutality. In Germany, Henry had to fight against the resistance of the Guelphs - in 1196 his plan for a hereditary empire failed. Instead, he pursued an ambitious and quite successful "Mediterranean policy", the goal of which may have been the conquest of the Holy Land or possibly even an offensive against Byzantium.

After the early death of Henry VI in 1197, the last attempt to create a strong central power in the empire failed. After the double election of 1198, in which Philip of Swabia was elected in March in Mulhouse/Thuringia and Otto IV in June in Cologne, two kings faced each other in the empire. Henry's son, Frederick II, had already been elected king in 1196 at the age of two, but his claims were swept aside. Philip had already largely asserted himself when he was assassinated in June 1208. Otto IV was then able to establish himself as ruler for a few years. His planned conquest of Sicily led to a break with his long-time patron Pope Innocent III. In the northern Alpine part of the empire, Otto's excommunication caused him to lose increasing support among the princes. The Battle of Bouvines in 1214 brought his reign to an end and brought the final recognition of Frederick II. After the disputes over the throne, a considerable development began in the empire to record customs in writing. The two law books, the Sachsenenspiegel and the Schwabenspiegel, are regarded as significant testimonies to this. Many arguments and principles that were to apply to the following royal elections were formulated at that time. This development culminated in the middle of the 14th century, after the experiences of the Interregnum, in the stipulations of the Golden Bull.

The fact that Frederick II, who had travelled to Germany in 1212 to assert his rights there, stayed in the German Empire for only a few years of his life and thus of his reign, even after his recognition, gave the princes more room for manoeuvre again. In 1220 Frederick granted the ecclesiastical princes in particular extensive rights in the Confoederatio cum principibus ecclesiasticis, in order to secure their consent to the election and recognition of his son Henry as Roman-German king. The privileges, known since the nineteenth century as the Confoederatio cum principibus ecclesiasticis and the Statutum in favorem principum (1232), formed the legal basis for the princes to extend their power into closed, independent sovereignties. However, they were not so much stations of loss of power for the kingship, but with the privileges a level of development was securitized that the princes had already reached in the expansion of their territorial rule.

In Italy, the highly educated Frederick II, who increasingly centralized the administration of the kingdom of Sicily along Byzantine lines, was embroiled for years in a conflict with the papacy and the cities of Upper Italy, with Frederick even being denigrated as the Antichrist. In the end, Frederick seemed to have gained the upper hand militarily, when the emperor, who had been declared deposed by the pope in 1245, died on 13 December 1250.

Late Middle Ages

At the beginning of the late Middle Ages, in the course of the fall of the Hohenstaufen dynasty and the subsequent interregnum, royal power declined until the time of Rudolf of Habsburg, although it had traditionally been weak anyway. At the same time, the power of the sovereigns and electors increased. Since the late 13th century, the latter had had the exclusive right to elect kings, so that subsequent kings often sought to pursue a concordant imperial policy with them. King Rudolf (1273-1291) once again succeeded in consolidating the kingship and securing the remaining imperial property as a result of the so-called revindication policy. Rudolf's plan for an imperial coronation failed, however, as did his attempt to impose a dynastic succession, which the imperial princes were not prepared to do. The House of Habsburg did, however, gain significant possessions in the southeastern part of the German Empire.

Rudolf's successor Adolf of Nassau sought rapprochement with the powerful kingdom of France, but his policies in Thuringia provoked resistance from the imperial princes, who united against him. In 1298 Adolf of Nassau fell in battle against the new king, Albrecht of Habsburg. Albrecht also had to contend with opposition from the electors, who disliked his plans to increase Habsburg domestic power and feared that he was planning to establish a hereditary monarchy. Although Albrecht was ultimately able to hold his own against the electors, he submitted to Pope Boniface VIII in an oath of obedience and surrendered imperial territories in the west to France. On 1 May 1308 he fell victim to the murder of a relative.

The intensified French expansion in the western borderlands of the empire from the 13th century onwards meant that the kingship's opportunities for exerting influence in the former kingdom of Burgundy continued to diminish; a similar but less pronounced tendency became apparent in imperial Italy (i.e. essentially in Lombardy and Tuscany). It was not until the Italian campaign of Henry VII. (1310-1313), there was a tentative revival of imperial Italian policy. King Henry VII, elected in 1308 and crowned in 1309, achieved extensive unity of the great houses in Germany and won the kingdom of Bohemia for his house in 1310. The House of Luxembourg thus rose to become the second important late medieval dynasty after the Habsburgs. In 1310 Henry set out for Italy. He was the first Roman-German king after Frederick II to also attain the imperial crown (June 1312), but his policies provoked opposition from the Guelfs in Italy, the pope in Avignon (see Avignonese papacy), and the French king, who saw a new, power-conscious emperorship as a danger. Henry died in Italy on August 24, 1313, as he was about to set out on a campaign against the kingdom of Naples. The Italian policy of the following late medieval rulers was much narrower than that of their predecessors.

In 1314, two kings were elected, the Wittelsbach Louis IV and the Habsburg Frederick. In 1325, a double kingship, hitherto completely unknown in the medieval empire, was created for a short time. After Frederick's death, Louis IV pursued a rather self-confident policy in Italy as sole ruler and carried out a 'papal-free' imperial coronation in Rome. This brought him into conflict with the papacy. In this intense dispute, the question of the papal claim to approval played a major role. In this regard, there were also debates on political theory (see William of Ockham and Marsilius of Padua) and finally an increased emancipation of the electors or the king from the papacy, which finally found its expression in 1338 in the Electoral Association of Rhense. From the 1330s onwards, Louis pursued an intensive policy of domestic power by acquiring numerous territories. In doing so, however, he disregarded consensual decision-making with the princes. This led to tensions with the House of Luxembourg in particular, who openly challenged him in 1346 with the election of Charles of Moravia. Louis died shortly afterwards and Charles ascended the throne as Charles IV.

The late medieval kings concentrated much more on the German part of the empire, at the same time relying more heavily than before on their respective domestic power. This resulted from the increasing loss of the remaining imperial property through an extensive policy of pledging, especially in the 14th century. Charles IV can be cited as a prime example of a house power politician. He succeeded in adding important territories to the Luxembourg household power complex; in return, however, he renounced imperial estates, which were pledged on a large scale and ultimately lost to the empire, and he also effectively ceded territories in the west to France. In return, Charles achieved a far-reaching settlement with the papacy and had himself crowned emperor in 1355, but renounced a resumption of the old Italian policy in the Hohenstaufen style. Above all, however, with the Golden Bull of 1356 he created one of the most important 'fundamental laws of the empire', in which the rights of the electors were finally laid down and which played a decisive role in determining the future policy of the empire. The Golden Bull remained in force until the dissolution of the Empire. Charles's reign also saw the outbreak of the so-called Black Death - the plague - which contributed to a severe mood of crisis and in the course of which there was a marked decline in the population and pogroms against the Jews. At the same time, however, this period also represented the heyday of the Hanseatic League, which became a major power in northern Europe.

With the death of Charles IV in 1378, the position of power of the Luxembourgers in the empire was soon lost, as the household power complex he had created rapidly disintegrated. His son Wenceslas was even deposed by the four Rhenish electors on 20 August 1400 because of his obvious incompetence. In his place, the Count Palatine of the Rhine, Ruprecht, was elected the new king. However, his power base and resources were far too limited to be able to govern effectively, especially as the Luxembourgers were not resigned to the loss of the kingship. After Ruprecht's death in 1410, Sigismund, who had already been king of Hungary since 1387, was the last Luxembourger to ascend the throne. Sigismund had to struggle with considerable problems, especially as he no longer had any domestic power in the empire, but in 1433 he attained the imperial dignity. Sigismund's political reach extended far into the Balkans and Eastern Europe.

In addition, there were ecclesiastical problems at this time, such as the Western Schism, which could only be eliminated under Sigismund with recourse to conciliarism. From 1419 onwards, the Hussite Wars posed a great challenge. The previously economically prosperous lands of the Bohemian crown were widely devastated as a result, and the neighboring principalities found themselves under constant threat from Hussite military campaigns. The conflicts ended in 1436 with the Basel Compacts, which recognized the Utraquist church in the kingdom of Bohemia and the margraviate of Moravia. The struggle against the Bohemian heresies led to an improvement in relations between the pope and the emperor. With the death of Sigismund in 1437, the House of Luxembourg became extinct in the direct line. The kingship passed to Sigismund's son-in-law Albrecht II and thus to the Habsburgs, who maintained it almost continuously until the end of the empire. Frederick III largely kept out of direct imperial affairs for a long time and had to contend with some political problems, such as the conflict with the Hungarian king Matthias Corvinus. However, Frederick ultimately secured the Habsburg position of power in the empire, the Habsburg claims to larger parts of the disintegrated ruling complex of the House of Burgundy, and the royal succession for his son Maximilian. The empire also underwent a structural and constitutional change during this period; in a process of 'designed consolidation' (Peter Moraw), relations between the members of the empire and the kingship became closer.

early modern period

Imperial Reform

→ Main article: Imperial reform (Holy Roman Empire)

Historians regard the early modern imperial rule of the empire as a new beginning and a reconstruction, and by no means as a reflection of the Hohenstaufen rule of the High Middle Ages. For the contradiction between the claimed sanctity, the global claim to power of the empire and the real possibilities of the emperorship had become too clear in the second half of the 15th century. This triggered a journalistically supported imperial constitutional movement, which was intended to revive the old "ideal states" but ultimately led to sweeping innovations.

Under the Habsburgs Maximilian I and Charles V, the emperorship regained recognition after its decline, and the office of emperor became firmly linked to the newly created imperial organization. In keeping with the reform movement, Maximilian initiated a comprehensive imperial reform in 1495, which provided for a perpetual land peace, one of the most important plans of the reform advocates, and an empire-wide tax, the Gemeiner Pfennig. It is true that these reforms were not fully implemented, for of the institutions that emerged from them only the newly formed Imperial Circles and the Imperial Chamber Court endured. Nevertheless, the reform was the basis for the modern empire. It gave it a much more precise system of rules and an institutional framework. For example, the possibility of bringing a suit against one's sovereign before the Imperial Chamber Court promoted peaceful conflict resolution in the empire. The interplay between the emperor and the imperial estates, which had now been established, was to be formative for the future. The Imperial Diet also emerged at this time and was the central political forum of the Empire until its end.

Reformation and religious peace

→ Main article: Reformation and Augsburg Imperial and Religious Peace

Decree, order, will, and command, therefore. That hereafter no one, whatever his dignity, status or nature, may for any reason whatsoever, as the names, have, even in whatsoever appearance this may happen, attack, war, rob, take, overrun, besiege the other, not to serve for himself or anyone else on his behalf, nor to descend from any castle, town, march, fortification, village, farm or village, or to take it without the will of the other with mighty violence, or to damage it dangerously with fire or in any other way.

§ 14 (Land Peace Formula) of the Augsburg Imperial and Religious Peace

On the one hand, the first half of the 16th century was marked by a further juridification and thus a further consolidation of the empire, for example through the enactment of imperial police regulations in 1530 and 1548 and the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina in 1532. On the other hand, the division of faith that arose during this period as a result of the Reformation had a disintegrating effect. The fact that individual regions and territories turned away from the old Roman Church put the empire to the test, not least because of its claim to sanctity.

The Edict of Worms of 1521, in which the imperial ban (after the papal church ban Decet Romanum Pontificem) was quasi obligatory imposed on Martin Luther, did not yet offer any leeway for a pro-Reformation policy. Since the edict was not observed throughout the empire, the decisions of the next imperial diets already deviated from it. The mostly imprecise and ambiguous compromise formulas of the imperial diets were the cause of new legal disputes. The Nuremberg Diet of 1524, for example, declared that everyone should obey the edict of Worms as much as possible. However, a definitive peace solution could not be found, and the people shifted from one compromise to the next, usually for a limited period of time.

This situation was not satisfactory for either side. The Protestant side had no legal security and lived for several decades in fear of a religious war. The Catholic side, especially Emperor Charles V, did not want to accept a permanent division of the faith of the Empire. Charles V, who at first did not really take the case of Luther seriously and did not realize its implications, did not want to accept this situation because, like the medieval rulers, he saw himself as the upholder of the one true church. The universal emperorship needed the universal Church; however, his coronation as emperor in Bologna in 1530 was to be the last one performed by a pope.

After a long period of hesitation, in the summer of 1546 Charles imposed the imperial ban on the leaders of the Protestant Schmalkaldic League and initiated the military execution of the empire. This conflict went down in history as the Schmalkaldic War of 1547/48. After the Emperor's victory, the Protestant princes had to accept the so-called Augsburg Interim at the Geharnischter Augsburger Reichstag of 1548, which at least granted them the lay chalice and priestly marriage. This outcome of the war, which was quite mild for the Protestant imperial estates, was due to the fact that Charles was pursuing not only religious-political goals but also constitutional-political ones, which would have led to an undermining of the estates' constitution and a quasi-central government of the emperor. These additional goals earned him the resistance of the Catholic imperial estates, so that no satisfactory solution to the religious question was possible for him.

The religious disputes in the empire were integrated into Charles V's conception of a comprehensive Habsburg empire, a monarchia universalis, which was to encompass Spain, the Austrian hereditary lands and the Holy Roman Empire. However, he did not succeed in making the emperorship hereditary, nor in having the imperial crown pass back and forth between the Austrian and Spanish lines of the Habsburgs. At the same time, Charles found himself in conflict with France, fought mainly in Italy, while the Turks conquered Hungary after 1526. The military conflicts tied up considerable resources.

The war of princes of the Saxon Elector Moritz of Saxony against Charles and the resulting Treaty of Passau of 1552 between the warlords and the later Emperor Ferdinand I were the first steps towards a lasting religious peace in the Empire, which led to the Imperial and Religious Peace of Augsburg in 1555. The reconciliation that thus took place, at least for the time being, was also made possible by the decentralized ruling structure of the empire, where the interests of the sovereigns and the empire repeatedly made it necessary to reach a consensus, whereas in France, with its centralized royal power, there was a bloody struggle between the Catholic royalty and individual Protestant leaders during the 16th century.

However, the Peace of Augsburg was not only important as a religious peace, it also had a significant constitutional role in that important constitutional policy decisions were made through the creation of the Imperial Execution Code. These steps had become necessary because of the Second Margravial War of Albrecht Alcibiades of Brandenburg-Kulmbach, which raged in the Franconian region from 1552 to 1554. Albrecht extorted money and even territories from various Frankish imperial territories. Emperor Charles V did not condemn this, he even took Albrecht into his service and thus legitimized the breach of the Perpetual Peace. Since the territories concerned refused to accept the theft of their territories, which had been confirmed by the Emperor, Albrecht laid waste to their lands. Meanwhile, troops under Moritz of Saxony formed up in the northern empire to fight Albrecht. An imperial prince and later King Ferdinand, not the emperor, had initiated military countermeasures against the peacebreaker. On July 9, 1553, the bloodiest battle of the Reformation in the Empire occurred, the Battle of Sievershausen, in which Moritz of Saxony died.

The Imperial Execution Statute adopted at the Diet of Augsburg in 1555 included the constitutional weakening of imperial power, the enshrinement of the imperial principle and the full federalization of the empire. In addition to their previous duties, the imperial districts and local imperial estates were given responsibility for enforcing judgments and appointing the assessors of the Imperial Chamber Court. In addition, they were given other important, hitherto imperial, responsibilities besides coinage. Since the emperor had proved incapable and too weak to perform one of his most important tasks, the preservation of peace, his role was now filled by the imperial estates associated in the imperial districts.

Just as important as the execution order was the religious peace proclaimed on September 25, 1555, which abandoned the idea of a confessionally uniform empire. The sovereigns were given the right to determine the confession of their subjects, succinctly summarized in the formula whose rule, whose religion. In Protestant territories, ecclesiastical jurisdiction passed to the sovereigns, making them a kind of spiritual head of their territory. Furthermore, it was stipulated that ecclesiastical imperial estates, i.e. archbishops, bishops and imperial prelates, had to remain Catholic. Although these and several other stipulations led to a peaceful solution to the religious problem, they also manifested the increasing division of the empire and, in the medium term, led to a blockade of the imperial institutions.

After the Diet of Augsburg, Emperor Charles V resigned from office and handed over power to his brother, the Roman-German King Ferdinand I. Charles's policies within and outside the Empire had finally failed. Ferdinand again limited the emperor's rule to Germany, and succeeded in bringing the imperial estates back into closer association with the emperorship, thus strengthening it once more. For this reason, Ferdinand is often referred to as the founder of the modern German Empire.

Confessionalization and the Thirty Years' War

→ Main article: Confessionalization and the Thirty Years' War

Until the beginning of the 1580s, there was a phase in the empire without major armed conflicts. The religious peace had a stabilizing effect and the imperial institutions such as the imperial circles and the imperial chamber court developed into effective and recognized instruments of peacekeeping. During this period, however, the so-called confessionalization took place, i.e. the consolidation and demarcation of the three confessions Protestantism, Calvinism and Catholicism from one another. The accompanying emergence of early modern forms of government in the territories brought constitutional problems to the empire. The tensions increased to such an extent that the empire and its institutions could no longer perform their function as arbitrators above the confessions and were effectively blocked at the end of the 16th century. As early as 1588, the Imperial Chamber Court was no longer able to act.

Since the Protestant estates at the beginning of the 17th century also no longer recognized the Imperial Court Council, which was occupied exclusively by the Catholic emperor, the situation escalated further. At the same time, the Electoral College and the Imperial Circles split into confessional groupings. An Imperial Diet in 1601 failed because of the antagonisms between the parties, and in 1608 an Imperial Diet in Regensburg ended without an imperial agreement because the Calvinist Electoral Palatinate, whose confession was not recognized by the Emperor, and other Protestant estates had left it.

Since the imperial system was largely blocked and the protection of peace was supposedly no longer given, six Protestant princes founded the Protestant Union on 14 May 1608. Other princes and imperial cities later joined the Union, but Electoral Saxony and the North German princes stayed away. In reaction to the Union, Catholic princes and cities founded the Catholic League on July 10, 1609. The League wanted to maintain the previous imperial system and preserve the predominance of Catholicism in the empire. The empire and its institutions had thus finally become blocked and unable to act.

The Defenestration of Prague then triggered the Great War, in which the Emperor initially achieved great military successes and also attempted to exploit these for his position of power vis-à-vis the imperial states. Thus, in 1621, Emperor Ferdinand II outlawed the Palatine Elector and Bohemian King Frederick V out of his own claim to power and transferred the electoral dignity to Maximilian I of Bavaria. Ferdinand had previously been elected emperor by all the electors, including the Protestant ones, on 19 August 1619, despite the beginning of the war.

The enactment of the Edict of Restitution on 6 March 1629 was the last significant legislative act of an emperor in the empire and, like the outlawing of Frederick V, arose from the imperial claim to power. This edict demanded the implementation of the Augsburg Imperial Peace according to Catholic interpretation. Accordingly, all the archbishoprics and bishoprics secularized by the Protestant sovereigns since the Treaty of Passau were to be returned to the Catholics. In addition to the recatholicization of large Protestant territories, this would have meant a significant strengthening of the imperial position of power, since until then questions of religious policy had been decided by the emperor together with the imperial estates and electors. Against this, a cross-confessional coalition of the electors was formed. They did not want to accept that the emperor issued such a drastic edict without their consent.

The electors forced the emperor at the Regensburg Electors' Day in 1630, under the leadership of the new Catholic elector Maximilian I, to dismiss the imperial generalissimo Wallenstein and agree to a review of the edict. Also in 1630, Sweden entered the war on the side of the Protestant imperial states. After the imperial troops had been outnumbered by Swedes for several years, the emperor once again gained the upper hand by winning the Battle of Nördlingen in 1634. In the subsequent Peace of Prague between the Emperor and Electoral Saxony of 1635, Ferdinand was forced to suspend the Edict of Restitution for forty years, starting from the status of 1627. But the head of the empire emerged stronger from this peace, since, with the exception of the Electoral Association, all imperial alliances were declared dissolved and the emperor was granted supreme command of the imperial army. However, the Protestants also accepted this strengthening of the emperor. The religious-political problem of the Edict of Restitution had in fact been postponed for 40 years, since the Emperor and most of the imperial estates agreed that the political unification of the empire, the cleansing of the empire's territory from foreign powers and the end of the war were the most urgent matters.

After France's open entry into the war, which took place in order to prevent a strong imperial Habsburg power in Germany, the balance shifted again to the disadvantage of the emperor. Here, at the latest, the original Teutonic confessional war within the empire had become a European hegemonic struggle. The war thus continued, since the confessional and constitutional problems, which had been settled at least provisionally in the Peace of Prague, were of secondary importance to the powers of Sweden and France, who were on imperial territory. Moreover, as already indicated, the Peace of Prague had serious shortcomings, so that the internal disputes within the empire also continued.

From 1641 onwards, individual imperial estates began to conclude separate peace treaties, as it was hardly possible to organise a broad-based resistance of the empire in the undergrowth of confessional solidarity, traditional alliance policy and the current war situation. In May 1641, the Elector of Brandenburg was the first major imperial state to make a start. He made peace with Sweden and dismissed his army, which was not possible under the terms of the Peace of Prague, since it was nominally part of the imperial army. Other imperial states followed; thus in 1645 Elector Saxony made peace with Sweden and in 1647 Elector Mainz with France.

Against the will of the emperor, since 1637 Ferdinand III, who originally wanted to represent the empire alone at the peace talks now in the offing in Münster and Osnabrück in accordance with the Peace of Prague, the imperial estates, who, supported by France, insisted on their liberty, were admitted to the talks. This dispute, known as the question of admissions, finally upset the system of the Peace of Prague, with the strong position of the emperor. Ferdinand originally intended to settle only the European questions in the Westphalian negotiations and to make peace with France and Sweden, and to deal with the German constitutional problems at a subsequent Imperial Diet, at which he could have appeared as a glorious bringer of peace. At this Diet, in turn, the foreign powers would have had no business.

Peace of Westphalia

→ Main article: Peace of Westphalia

Let there be a Christian universal and perpetual peace [...] and let it be sincerely and earnestly observed and observed, that each part may promote the benefit, honour and advantage of the other, and that both on the part of the whole Roman Empire with the Kingdom of Sweden and on the part of the Kingdom of Sweden with the Roman Empire faithful neighbourliness, true peace and genuine friendship may grow and blossom anew.

First Article of the Treaty of Osnabrück

The Emperor, Sweden and France agreed on peace negotiations in Hamburg in 1641, while the hostilities continued. The negotiations began in 1642/43 in parallel in Osnabrück between the emperor, the Protestant imperial estates and Sweden and in Münster between the emperor, the Catholic imperial estates and France. The fact that the Emperor did not represent the Empire alone was a symbolically important defeat. The imperial power that had emerged strengthened from the Peace of Prague was once again up for grabs. The imperial estates, of whatever confession, considered the Prague order so dangerous that they saw their rights better safeguarded if they did not sit opposite the emperor alone, but if the negotiations on the imperial constitution took place under the eyes of foreign countries. This, however, also suited France very well, which was anxious to limit the power of the Habsburgs and therefore advocated the participation of the imperial estates.

Both negotiating cities and the communication routes between them had been declared demilitarized in advance (but this was only carried out for Osnabrück) and all legations were given free passage. Delegations from the Republic of Venice, the Pope, and Denmark traveled to mediate, and representatives of other European powers flocked to Westphalia. In the end, all European powers except the Ottoman Empire, Russia and England were involved in the negotiations. The negotiations in Osnabrück, along with those between the Empire and Sweden, effectively became a constitutional convention at which constitutional and religious policy problems were dealt with. In Münster, negotiations were held on the European framework and the changes in feudal law with regard to the Netherlands and Switzerland. Furthermore, the Peace of Münster between Spain and the Republic of the Netherlands was negotiated here.

Until the end of the 20th century, the Peace of Westphalia was seen as destructive for the empire. Fritz Hartung justified this with the argument that the peace treaty had deprived the emperor of all leverage and granted the imperial estates almost unlimited freedom of action, and that the empire had been "fragmented" and "crumbled" as a result - it was therefore a "national disaster". Only the religious-political question had been solved, but the empire had lapsed into rigidity, which had ultimately led to its disintegration.

In the period immediately after the Peace of Westphalia and even during the 18th century, on the other hand, the conclusion of peace was viewed quite differently. It was greeted with great joy and was regarded as a new fundamental law that applied wherever the emperor was recognized with his prerogatives and as a symbol of the unity of the empire. By its provisions, the Peace placed the territorial sovereignties and the various confessions on a uniform legal footing and codified the tried and tested mechanisms created after the constitutional crisis of the early 16th century, rejecting those of the Peace of Prague. Georg Schmidt writes in summary:

"Peace did not produce state fragmentation or princely absolutism. [...] The peace emphasized the freedom of the estates, but did not make the estates into sovereign states."

All imperial states were granted full sovereign rights and the right of alliance, which had been annulled in the Peace of Prague, was restored. However, this did not mean the full sovereignty of the territories, which can also be seen from the fact that this right is listed in the text of the treaty in the midst of other rights that had already been exercised for some time. The right of alliance - this also contradicts a full sovereignty of the territories of the empire - was not allowed to be directed against the emperor and the empire, the truce or against this treaty and, according to the opinion of contemporary legal scholars, was in any case a long-established customary right (see also the section Herkommen und Gewohnheitsrecht) of the imperial estates, which was only fixed in writing in the treaty.

In the religious-political part, the imperial estates practically deprived themselves of the power to determine the confession of their subjects. Although the Augsburg Religious Peace was confirmed as a whole and declared inviolable, the disputed questions were newly regulated and legal relationships were fixed at the status of 1 January 1624 or reset to the status on this date. All imperial estates, for example, had to tolerate the other two confessions if they already existed on their territory in 1624. All property had to be returned to the owner at the time, and all subsequent provisions to the contrary by the Emperor, the Imperial Estates or the occupying powers were declared null and void.

The second religious peace certainly did not bring any progress for the idea of tolerance or for individual religious rights or even human rights. But that was not its aim either. It was supposed to have a peacemaking effect through further juridification. Peace and not tolerance or secularization was the goal. That this succeeded despite all setbacks and occasional fatalities in later religious conflicts is obvious.

The Treaties of Westphalia brought the long-awaited peace to the Empire after thirty years. The Empire lost some territories to France and effectively released the Netherlands and the Old Confederation from the imperial union. Otherwise, not much changed in the empire; the system of power between the emperor and the imperial estates was rebalanced without shifting the weights much compared to the situation before the war, and imperial politics was not deconfessionalized, but only the dealings of the confessions were reorganized. Neither was

"[the] imperial union condemned to torpor nor blown up - these are research myths long fervently cherished. Viewed soberly, the Peace of Westphalia, this alleged national disaster, loses much of its horror, but also much of its supposedly epochal character. That it destroyed the imperial idea and the imperial state is the most blatant of all the circulating misconceptions about the Peace of Westphalia."

Until the middle of the 18th century

After the Peace of Westphalia, a group of princes, united in the Princes' Association, pressed for radical reforms in the empire, which were intended in particular to limit the supremacy of the electors and to extend the royal electoral privilege to other imperial princes as well. At the Imperial Diet of 1653/54, however, which according to the provisions of the peace should have taken place much earlier, this minority was unable to prevail. In the imperial decree of this Diet, called the Youngest - this Diet was the last before the permanence of the body - it was decided that subjects would have to pay taxes to their lords so that the latter could maintain troops. This often led to the formation of standing armies in various larger territories. These were known as the Armierte Reichsstände.

Also, the empire did not disintegrate because too many estates had an interest in an empire that could guarantee their protection. This group included especially the smaller estates, which could practically never become a state of their own. The aggressive, expansionist policy of France on the western border of the empire and the Turkish danger in the east also made clear to almost all estates the need for a sufficiently cohesive imperial federation and an imperial leadership capable of acting.

Since 1658 Emperor Leopold I, whose work has only been studied in more detail since the 1990s, ruled the empire. His actions are described as prudent and far-sighted, and measured against the initial situation after the war and the low point of the imperial reputation, they were also extraordinarily successful. By combining various instruments of rule, Leopold succeeded in binding not only the smaller but also the larger imperial estates to the imperial constitution and the imperial state. Particularly noteworthy here are his marriage policy, the means of raising the estates and the bestowal of all manner of euphonious titles. Nevertheless, the centrifugal forces of the empire intensified. The award of the ninth electoral dignity to Ernst August of Hanover in 1692 stands out in particular. The concession to the Brandenburg Elector Frederick III to be crowned King of Prussia in 1701 for the Duchy of Prussia, which did not belong to the Empire, also falls into this category.

After 1648, the position of the imperial districts was further strengthened and they were given a decisive role in the imperial war constitution. Thus, in 1681, due to the threat posed to the Empire by the Turks, the Imperial Diet adopted a new Imperial War Constitution in which the troop strength of the Imperial Army was set at 40,000 men. The Imperial Districts were to be responsible for the deployment of the troops. The Perpetual Diet offered the emperor the opportunity to bind the smaller imperial estates to himself and to win them over to his own policies. The emperor also succeeded in increasing his influence on the empire again through the improved possibilities of arbitration.

The fact that Leopold I opposed the reunion policy of the French king Louis XIV and tried to persuade the imperial circles and estates to resist the French annexation of imperial territories shows that imperial policy had not yet become a mere appendage of Habsburg great power policy, as it had under his successors in the 18th century. It was also during this period that the great power Sweden was successfully pushed back from the northern territories of the empire in the Swedish-Brandenburg War and the Great Northern War.

Dualism between Prussia and Austria

From 1740 onwards, the two largest territorial complexes of the empire, the Archduchy of Austria and Brandenburg-Prussia, began to grow more and more out of the imperial federation. After defeating the Turks in the Great Turkish War after 1683, the House of Austria was able to acquire large territories outside the empire, shifting the focus of Habsburg policy to the southeast. This became particularly evident under the successors of Emperor Leopold I. The situation was similar with Brandenburg-Prussia, which also had part of its territory outside the empire. However, the increasing rivalry, which placed a great strain on the structure of the empire, was compounded by changes in the thinking of the time.

Whereas until the Thirty Years' War it was very important for a ruler's reputation what titles he possessed and at what position in the hierarchy of the empire and the European nobility he stood, other factors such as the size of the territory and economic and military power now came more to the fore. The view prevailed that only the power that resulted from these quantifiable data actually counted. According to historians, this is a late consequence of the Great War, in which time-honored titles, claims, and legal positions, especially of the smaller imperial estates, almost ceased to play a role and were subordinated to fictitious or actual constraints of the war.

However, these categories of thought were not compatible with the previous system of the empire, which was supposed to guarantee the empire and all its members legal protection of the status quo and protect them from a preponderance of power. This conflict is evident, among other things, in the work of the Imperial Diet. Its composition distinguished between electors and princes, high aristocracy and urban magistrates, Catholic and Protestant, but not, for example, between estates that maintained a standing army and those that were defenceless. This discrepancy between actual power and time-honoured hierarchy led to the desire of the large, powerful estates for a loosening of the imperial federation.

Added to this was the thinking of the Enlightenment, which questioned the conservative preserving character, the complexity, even the idea of the empire itself, and portrayed it as "unnatural". The idea of human equality could not be reconciled with the idea of empire, which was to preserve what existed and to secure for each estate its assigned place in the structure of the empire.

In summary, it can be said that Brandenburg-Prussia and Austria no longer fit into the imperial federation, not only because of their sheer size, but also because of the internal constitution of the two territories that had become states. Both had reformed the Länder, which had originally been decentralized and based on the estates, and had broken the influence of the estates. Only in this way could the various inherited and conquered respective lands be sensibly administered and preserved, and a standing army financed. This path of reform was closed to the smaller territories. A sovereign who undertook reforms of this magnitude would inevitably have come into conflict with the imperial courts, since these would have stood by the estates, against whose privileges a sovereign would have had to violate. The emperor in his role as Austrian sovereign naturally did not have to fear the Imperial Court he occupied as much as other sovereigns, and in Berlin they hardly cared about the imperial institutions anyway. An execution of the sentences would have been factually impossible. This different internal constitution of the two great powers also contributed to the alienation from the empire.

The rivalry between Prussia and Austria, known as dualism, gave rise to several wars in the 18th century. Prussia won the two Silesian Wars and received Silesia, while the War of the Austrian Succession ended in Austria's favor. During the War of Succession a Wittelsbach came to the throne with Charles VII, but could not prevail without the resources of a great power, so that after his death in 1745 a Habsburg(-Lorraine) was again elected with Francis I Stephen of Lorraine, Maria Theresa's husband.

These conflicts were devastating for the empire. Prussia did not want to strengthen the Empire, but to use it for its own purposes. The Habsburgs, too, who had been disgruntled by the alliance of many imperial estates with Prussia and the election of a non-Habsburg to the imperial throne, were now much more clearly committed than before to a policy that related solely to Austria and its power. The title of emperor was sought almost solely because of its sound and superior rank to all European rulers. The imperial institutions had degenerated into sideshows of power politics, and the constitution of the empire no longer had much to do with reality. Prussia tried to hit the Emperor and Austria by instrumentalizing the Imperial Diet. Emperor Joseph II in particular withdrew almost completely from imperial politics. Joseph II had initially tried to reform the imperial institutions, especially the Imperial Chamber Court, but failed due to the resistance of the imperial estates, which wanted to break away from the imperial union and therefore no longer let the court interfere in their 'internal' affairs. Joseph gave up in frustration.

But Joseph II also acted unhappily and insensitively in other respects. Joseph II's Austria-centred policy during the War of the Bavarian Succession in 1778/79 and the peace settlement of Teschen brokered from abroad were a disaster for the empire. When the Bavarian line of the Wittelsbach dynasty died out in 1777, this seemed to Joseph a welcome opportunity to annex Bavaria to the Habsburg lands. Austria therefore made legally questionable claims to the inheritance. Under massive pressure from Vienna, the heir from the Palatine line of the Wittelsbach dynasty, Elector Karl Theodor, agreed to a treaty that ceded parts of Bavaria. It was suggested to Karl Theodor, who had been reluctant to accept the inheritance in any case, that an exchange would later be made with the Austrian Netherlands, which comprised roughly the area of present-day Belgium. Joseph II, however, instead occupied the Bavarian territories to create a fait accompli, thus encroaching on an imperial territory as emperor.

These events allowed the Prussian King Frederick II to elevate himself to the position of protector of the empire and the small imperial estates and thus, as it were, to the position of "counter-emperor". Prussian and Elector Saxon troops marched into Bohemia. In the Peace of Teschen of May 13, 1779, which was enforced by Russia, Austria was granted the Innviertel. Nevertheless, the Emperor was the loser. For the second time since 1648, an internal German problem had to be settled with the help of foreign powers. It was Russia, not the Emperor, that brought peace to the Empire. Russia, in addition to its role as a guarantor power of the Peace of Teschen, became a guarantor power of the Peace of Westphalia and thus one of the "guardians" of the imperial constitution. The imperial state had dismantled itself and the Prussian King Frederick stood as the protector of the Empire. But it was not the protection and consolidation of the empire that had been Frederick's aim, but a further weakening of the emperor's position in the empire and thus of the whole imperial federation itself. He had achieved this goal.

The concept of a Third Germany, on the other hand, born of the fear that the smaller and medium-sized imperial estates would degenerate into a mere disposal mass of the large ones, in order to speak with one voice and thus push through reforms, failed due to the prejudices and antagonisms between the Protestant and Catholic imperial princes, as well as the self-interests of the electors and the large imperial cities. In the end, only the imperial cities, the imperial knighthoods and, to a certain extent, the ecclesiastical territories were the actual bearers of the imperial idea, although the latter were often ruled by members of imperial dynasties and represented their interests (e.g. the Electorate of Cologne, which was under a Wittelsbach archbishop during the War of the Spanish Succession). The emperor, too, acted more like a territorial ruler, aiming at the expansion of his immediate dominion territory and less at the preservation of an 'imperial interest'. By many contemporaries in the Age of Enlightenment, therefore, the Empire was perceived as an anachronism. Voltaire spoke derisively of the "empire that is neither Roman nor holy".

End of the Empire

First coalition wars against France

In the First Coalition War, the two great German powers (Austria and Prussia) formed an alliance of convenience against the French revolutionary forces. This alliance of February 1792, known as the Pillnitz Pact, was not aimed at protecting imperial rights, but rather at containing the revolution, primarily because it was feared that it would spread to imperial territory. Emperor Franz II squandered the opportunity to win the support of the other imperial estates. Emperor Franz II, who was elected emperor on 5 July 1792 with unusual haste and unanimity, squandered the opportunity by insisting on enlarging Austria's territory, if necessary at the expense of other members of the empire. And Prussia, too, wished to indemnify herself for her war expenses by annexing ecclesiastical imperial territories. Accordingly, it was not possible to build up a united front against the French revolutionary troops and to achieve major military successes.

Disappointed by the lack of success and in order to be better able to deal with the resistance to the renewed partition of Poland, Prussia concluded a separate peace with France in 1795, the Peace of Basel. In 1796 Baden and Württemberg also made peace with France. In both agreements, the respective possessions on the left bank of the Rhine were ceded to France. The owners, however, were to be "compensated" at the expense of ecclesiastical territories on the right bank of the Rhine, i.e. these were to be secularized. Other imperial states negotiated an armistice or neutrality.

In 1797, Austria also made peace and signed the Peace of Campo Formio, in which it ceded various possessions within and outside the empire, in particular the Austrian Netherlands and the Duchy of Tuscany. As compensation, Austria was also to be compensated at the expense of ecclesiastical territories to be secularized or other parts of the empire. Both greats of the empire thus held themselves harmless to other smaller members of the empire and even gave France a say in the future shape of the empire. In particular, the Emperor, acting as King of Hungary and Bohemia, but still obligated as Emperor to preserve the integrity of the Empire and its members, had allowed other imperial estates to be harmed for the "compensation" of a few, thus irreparably dismantling the Empire.