HIV

![]()

HTLV-III and Human T-lymphotropic virus 3 are redirects to this article. HTLV-III is also the name of a retrovirus of the genus Deltaretrovirus discovered in 2005, see HTLV.

![]()

This article describes the human immunodeficiency virus in the virus genus Lentivirus. The disease caused by it is presented in the article AIDS.

The human immunodeficiency virus, usually abbreviated as HIV (also HI virus) or also referred to as human immunodeficiency virus, is an enveloped virus that belongs to the retrovirus family and the lentivirus genus. An untreated HIV infection usually leads to AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) after a latency period of varying length, usually several years without symptoms.

The spread of HIV has become a pandemic since the early 1980s, and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimates that it has claimed some 39 million lives to date.

At the end of 2014, an estimated 36.9 million people worldwide were infected with HIV, with an equal distribution between both sexes. In Germany, about 87,900 people were living with HIV infection at the end of 2018, 80% of whom were men. In Austria, about 18,000 infected people were living in 2011, of which 5,200 were women. In Switzerland, there were about 20,000 people living with HIV in 2013, of whom 6,100 were women.

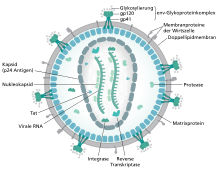

Structure and composition of the HI virus

HIV belongs to the complex retroviruses, i.e. in addition to the canonical retroviral genes gag, pol and env, the viruses possess further regulatory and accessory reading frames, namely in HIV-1 tat, rev, vif, vpu, vpr and nef.

The virus particle (virion) has a diameter of about 100 to 120 nanometers, which is above average for a virus, but significantly smaller than, for example, erythrocytes (diameter 7500 nanometers). HIV is surrounded by a lipid bilayer, which was separated from the human host cell during budding. Accordingly, various membrane proteins of the host cell are located in the viral envelope. Also embedded in this envelope are about 10 to 15 so-called spikes per virion, env-glycoprotein complexes of about ten nanometres in size; the density of the spikes is thus quite low, but there would be room for 73 ±25 of these projections on the surface of an HIV particle. An HIV spike consists of two subunits: Three molecules of the external surface glycoprotein gp120 are non-covalently bound to three molecules of the transmembrane envelope glycoprotein gp41. Gp120 is critical for binding of the virus to the CD4 receptors of target cells. Since the envelope of the HI virus originates from the host cell membrane, it also contains various host cell proteins, for example HLA class I and II molecules as well as adhesion proteins.

The matrix proteins p17 encoded by gag are associated with the inner side of the membrane. Inside the virion is the viral capsid, which is composed of the capsid proteins encoded by gag. The capsid protein p24 can be detected as an antigen in fourth generation HIV assays. In the capsid, associated with the nucleocapsid proteins encoded by gag, is the viral genome (9.2 kb) in the form of two copies of the single-stranded RNA. The nucleocapsid proteins have the function of protecting the RNA from degradation after entry into the host cell. Also located in the capsid are the enzymes reverse transcriptase (RT), integrase, and some of the accessory proteins. The protease is significantly involved in particle formation and is therefore found throughout the virus particle.

Structure of the RNA genome of HIV-1 consisting of nine genes

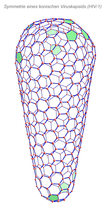

Complex conical capsid in HIV-1

Structure of the HI virion

History

HIV is the name recommended by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) in 1986. It replaces the former designations such as lymphadenopathy-associated virus (LAV), human T-cell leukemia virus III (HTLV-III) or AIDS-associated retrovirus (ARV).

HIV type 1 was first described in 1983 by Luc Montagnier and Françoise Barré-Sinoussi of the Institut Pasteur in Paris, and as early as June 1983 Der Spiegel covered HIV in its cover story ("Die tödliche Seuche Aids").

In the same issue of the journal Science, Robert Gallo, the head of the Tumor Virus Laboratory at the NIH in Bethesda, also published the discovery of a virus that he believed could cause AIDS. In that publication, however, he described the isolation of human T-cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-1; shortly thereafter, also of HTLV-2) from AIDS patients, which happened to be present in his samples alongside the HI virus, and did not also isolate the HI virus until about a year later. In a press conference with the then Secretary of Health and Human Services of the United States, Margaret Heckler, he publicly announced on April 23, 1984, that AIDS was caused by a virus that he had discovered.

Both Montagnier and Gallo claimed first discovery. This was followed by years of litigation, which also involved the patent for the newly developed HIV test. In 1986, HIV-2 was discovered.

The two researchers Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Luc Montagnier were awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 2008 for the discovery of the HI virus. The fact that Gallo was not included in this award was met with criticism in part by the virology community.

In May 2005, an international team of researchers succeeded in proving for the first time that the origin of HIV lies in monkeys. The research team took 446 faecal samples from free-living chimpanzees in the wilderness of the central African country of Cameroon. Several samples showed antibodies against Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV), the chimpanzee version of HIV, as the team published in the US journal Science. Twelve samples were almost identical to HIV-1 in humans. The team stressed that the antibodies had previously only been detected in chimpanzees in captivity. However, chimpanzees are not the original source of HIV. They are believed to have been infected with SIV or a precursor of this virus in other ape species in west-central Africa. Around the beginning of the 20th century, humans were infected for the first time with SIV, which subsequently mutated in their organisms into the AIDS-causing HIV. This means that the virus has already crossed the species barrier at least twice, from monkeys to apes and then to humans. How the virus was transmitted to humans is unclear. It is assumed that hunters who hunted and ate apes were infected with the virus for the first time, for example through minor open wounds.

Another thesis was that a vaccine against poliomyelitis (polio) in 1959 had been contaminated by monkeys carrying the virus (see also controversy over the origin of AIDS). According to this thesis, chimpanzee kidneys were used to propagate the vaccine in the former Belgian Congo and then hundreds of thousands of people were inoculated by oral vaccination, whereby SIV was transmitted to humans and mutated into HIV. However, an analysis of the mutations showed that there was a 95 percent probability that the origin of strain HIV-1 pre-dated 1930. In February 2000, a sample of the oral vaccines distributed was found and examined. It showed no traces of either HIV or SIV.

The oldest infected person whose HIV infection has been proven with certainty on the basis of blood samples comes from Belgian Congo and from the year 1959. In the initial publication on this serum sample, however, it was stated that the origin of the sample had not been clarified with certainty, so it is also possible that a person was infected for the first time in what was then French Equatorial Africa. A DNA paraffin sample of almost the same age from 1960, also from Belgian Congo, differs significantly genetically from the first sample, suggesting that HIV was present in Africa long before 1960. By means of statistical analyses (so-called molecular clock), the time window for the first appearance can be narrowed down with high probability to the years between 1902 and 1921. During this period, the African natives, who served as workers and carriers of raw materials, among other things, were treated against sleeping sickness by the Belgian colonial rulers in the Congo. For this purpose, syringes that had not been disinfected and were therefore infected with HIV were used for several people. In addition, rather poor medical and hygienic conditions were compounded by newly introduced diseases (including syphilis from Europe), which further weakened the population and made them vulnerable. The carrier columns could also have contributed to bringing the HI virus from the interior to the coast, so that it could be spread further from there.

When HIV first appeared in the USA, i.e. at the starting point of the AIDS pandemic, has long been the subject of research with varying, sometimes controversial results. As early as 1968, AIDS-like symptoms were observed in the patient Robert Rayford and later identified as HIV. However, it could not be conclusively proven that this was the HIV circulating today. According to a recent paper from 2016, the virus (HIV-1 subtype B) is estimated to have traveled from Africa to Haiti in 1967 and from there to the United States around 1971, demonstrating that Gaëtan Dugas, long thought to be Patient Zero, could not have been the first infected person in North America. The data refer to phylogenetic extrapolations. The earliest serological evidence is found in samples from San Francisco and New York City, both from 1978 onwards.

The theory that the AIDS pandemic was caused by a laboratory accident in the USA was created by the KGB in the course of Operation Infection and is classified as a conspiracy theory. In the 1980s, Jakob Segal developed a hypothesis in Berlin with a presumably scientific background, which also assumes a laboratory accident at Fort Detrick as the trigger of the AIDS pandemic, but which, in deviation from the KGB's representations, assumes genetic recombination from a Visna virus and HTLV-I as the artificial origin of HIV-1.

Robert Gallo (early 1980s).

Luc Montagnier (2008)

Françoise Barré-Sinoussi (2008)

Questions and Answers

Q: What is HIV?

A: HIV stands for Human immunodeficiency virus and is a type of Lentivirus which infects the human immune system.

Q: What kind of virus is HIV?

A: HIV is a retrovirus.

Q: What is the function of the human immune system that HIV infects?

A: The human immune system fights off infections.

Q: Can HIV cause AIDS?

A: Yes, HIV may cause AIDS.

Q: How does HIV kill the white blood cells?

A: HIV kills the white blood cells which a healthy body uses to fight diseases.

Q: What are the consequences of HIV killing the white blood cells which fight diseases?

A: The consequences of HIV killing the white blood cells are that the body becomes more vulnerable to infections and diseases.

Q: Is there a cure for HIV?

A: Currently, there is no cure for HIV, but treatment can help manage it and prevent it from progressing to AIDS.

Search within the encyclopedia