History of Spain

The history of Spain covers the developments in the territory of the Kingdom of Spain from prehistory to the present. It goes back 1.4 million years. Neanderthal man probably disappeared 45,000 years ago, possibly without encountering modern man. The Neolithic (from the 6th millennium BC), the transition from the appropriating way of life of hunters, fishermen and gatherers to the producing, ultimately farming way of life began through immigration from the central Mediterranean region.

From the 10th century BC onwards, there is evidence of trade by Phoenician seafarers with the coastal regions of southern Spain. From the 8th century B.C. at the latest, they founded colonies that served as bases for trade; later Greeks followed, especially from Phocaean Massalia. In the 5th and 4th centuries BC, Celtic tribes arrived on the peninsula from the north and mixed with the native Iberians in the northern and western regions (see Celtiberians). During the Punic Wars, the Carthaginians, who descended from the Phoenicians, conquered much of the south and east of the peninsula. After the defeat of Carthage, the Romans conquered the entire peninsula in a long process. The province of Hispania developed into an important part of the Roman Empire.

When the Western Roman Empire collapsed in the 5th century, Visigoths conquered the country. Their rule was ended by Muslim armies beginning in 711. These mountain groups, known as Moors, conquered most of the Iberian Peninsula until the Goth Pelayo (he is attested only in a forged chronicle) ended their advance at the Battle of Covadonga in northern Spain. In retrospect, this event was to mark the beginning of the reconquest of the country by the Christians, the so-called Reconquista. Moorish Spain became independent of the Arab world empire after 750, and in 929 Abd ar-Rahman III proclaimed Al-Andalus its own caliphate. Disputes between the noble families caused the caliphate to break up into numerous small kingdoms after a century.

Meanwhile, the unification process in the north was driven primarily by Castile. The kingdom of León was conquered by King Ferdinand the Great in 1037; in addition, the Castilians pursued imperial goals and temporarily assumed the title of emperor. The two kingdoms broke apart again in 1157, when King Alfonso VII made a division of the inheritance. Around 1230, they were reunited in the Kingdom of Castile by Ferdinand III. In 1469 Isabella, heir to the throne of Castile, and Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Aragon, married. After the assumption of government in 1474 in Castile and 1479 in Aragon, they ruled the dominions together. This did not result in the unification of the kingdoms into one state.

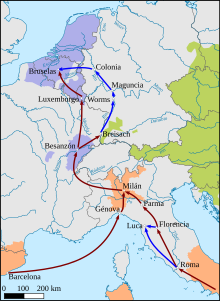

In 1492, Christian troops conquered the last territory ruled by Muslim rulers on the Spanish peninsula. Also in 1492, Columbus discovered America. After the death of Queen Isabella I of Castile, in 1504, her daughter Joan I was proclaimed Queen of Castile. Her marriage to Philip, the son of the Roman-German Emperor Maximilian, established a permanent link between the Spanish kingdoms and the House of Habsburg (Casa de Austria in Spanish). Their son, King Charles I became Holy Roman Emperor as Charles V. After Charles resigned from all offices in 1556, his dominions were divided between the Spanish and Austrian lines of the Habsburgs.

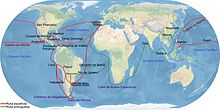

When the last king of the Spanish line of Habsburgs, Charles II, died without descendants in 1700, he was succeeded by Philip of Bourbon, the grandson of the French king Louis XIV. The War of the Spanish Succession was fought across much of Western Europe. A century later, Napoleon, who had assumed rule in France after the French Revolution (1789 to 1799), installed his brother Joseph Bonaparte as king in Spain. The Spanish fought back in a protracted guerrilla war. After Napoleon's defeat, Ferdinand VII returned to Spain as king. He was succeeded in 1833 by his daughter Isabella II (then two years old), who ruled until 1868. After the resignation of Amadeus of Savoy, elected king in 1870, the First Spanish Republic was proclaimed in 1873. A coup restored the monarchy under Alfonso XII in 1874. At the end of the war against the United States, Spain lost its colonies in the Caribbean and Pacific Oceans in 1898. Spain did not participate in the First World War. The Great Depression hit Spain much harder than other countries because of its low foreign trade links. King Alfonso XIII's association with the dictator Miguel Primo de Rivera discredited the monarchy; on April 14, 1931, Niceto Alcalá Zamora proclaimed the Second Republic.

Tensions between the Republican government and the anarchists rooted in Catalonia and the nationalist opposition finally culminated in the civil war of 1936 to 1939, in which Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union also intervened militarily. The nationalists under Francisco Franco prevailed in 1939. Franco kept Spain out of World War II, but his dictatorship led to political and economic isolation.

This isolation could only be broken after his death in 1975, and a constitutional monarchy emerged. Juan Carlos I opposed an attempted coup in 1981. Prime Minister Adolfo Suarez implemented reforms that brought about the transition to democracy. Spain joined NATO in 1982 and the European Community in 1986 and introduced the euro as cash in 2002. In 2007, a real estate bubble burst in Spain; in 2008, the country entered the financial crisis. At the same time, separatist movements, especially in Catalonia, grew stronger.

Monument in memory of the Cortes of Cadiz (1810-1813), which created the first Spanish Constitution.

Spain around the year 1200, at about the historical turning point of the Reconquista

_obra_de_l'escultor_Josep_Font.JPG)

Diorama of the Altamira Cave (Museu d'Arqueologia de Catalunya, Barcelona)

Paleolithic

Old Paleolithic

The oldest human remains in Spain are believed to be a 1.4 million-year-old tooth discovered in 2013 in Barranco León, a gorge near Granada. The fossils from the Sierra de Atapuerca have been dated to 1.3 million years.

Finds of the time around 800,000 before today are comparatively frequent in Spain, as in the Cueva de Santa Ana in the Extremadura, those from the time before 550,000 are however rare, again more frequently between 524,000 and 470,000. A certain population increase can be grasped for the time before 339,000 to 303,000 years. Fist wedges are known from about 900,000 years ago from the site of Cueva Negra del Estrecho del Río Quípar in the southeast, but they are controversial. Flint bifaces are dated to about 760,000 years from La Solana del Zamborino, also located in southeastern Spain.

Important sites of the Early Acheuléen, defined by the existence of said handaxes, are Villapando, San Quirce, La Maya III, El Espinar, La Mesa and Espinilla Sima de los Huesos. Important sites of the Middle Acheuléen are Cuesta de la Bajada, Gran Dolina 10-11 or Galeria Torralba and Ambrona, of the later phases including the End Acheuléen El Castillo (Cantabria), Lezetxiki, Solana del Zamborino (Granada) or Oxigeno (Madrid).

At the Sima de los Huesos site, about 1300 bones and teeth were found from 25 individuals who lived 600,000 years ago. The average height of the men was 174.4 cm, that of the women 161.9 cm. The site is believed to have been a burial ground. Only one stone implement was found among the bones, an unused hand axe made of quartzite with ochre. Excalibur could be a funerary object, indicating emotional feeling, symbolic and reflexive thinking, and an engagement with death.

Middle Paleolithic: Neanderthal man

The everyday use of fire had become established at the latest 300,000 years ago.

In contrast to the earlier Neanderthals, there is evidence of large-scale cultural differentiation for the late ones, such as in central and northwestern Europe, in Italy, in central and southwestern France including the Pyrenees region, then in the rest of the Iberian Peninsula. Neanderthal man was a big game hunter. Some of the finds, such as at Jarama VI (Guadalajara province) not far from Madrid, and Zafarraya, a cave near Málaga, have been dated to 45,000 years ago.

The question of whether Neanderthals and Cro-Magnons, who migrated from Africa, lived simultaneously on the peninsula plays an important role in the discussion of the genesis of Upper Paleolithic small-scale art. By 39,600 years BP, a cold steppe was located north of the Ebro River, whereas forests typical of the temperate and warm-temperate climatic zones existed south of the river. This boundary must have offered considerable resistance to the spread of modern man. This could explain the relatively late arrival of Homo sapiens in the south of the peninsula.

The northeastern Spanish site of Las Fuentes de San Cristóbal in the east of the province of Huesca, whose finds can be a maximum of 55,000 years old, shows a phase of lack of use in which neither Neanderthals nor ancestors of modern humans used the cave. This would support the thesis that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals never met in Western Europe. A temporal gap between the use of a site by Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans is also found in the Cova Gran de Santa Linya. Between the find layers lies a "sterile" layer without human traces.

Upper Paleolithic: anatomically modern man

Reliably assignable to Ice Age, anatomically modern humans (so-called Cro-Magnon man) is the Aurignacian, which corresponds to a calendar age of at least 40,000 (possibly 45,000) to about 31,000 years before present.

The following archaeological culture is the Gravettian, for which the sprinkling of the dead with ocher is typical. Its spread to the southwest of the peninsula around 32,000 BP was long considered a uniform process. The Gravettian, and with it Homo sapiens for the first time, reached the Betic Cordillera of the south between 34,000 and 25,000 cal BP.

Some groups shifted their diet to marine animals. Follow-up studies at Tito Bustillo Cave showed that the group there fed particularly on the common limpet and the large periwinkle.

Paintings of Homo sapiens can be found in the Altamira Cave near Santillana del Mar in Cantabria, where more than 150 murals dating from 16,000 to 14,000 BC can be seen. Other cave paintings, some as old as 20,000 years, have been discovered at La Pileta near Ronda and in a cave near Nerja (both in the province of Málaga). A number of engravings and wall paintings were found in Ekain and Altxerri B caves, both near San Sebastián (see Paleolithic Cave Paintings in Northern Spain). At Cueva del Mirón in Cantabria, the elaborately decorated, nearly 19,000-year-old skeleton of a young woman was recovered, known as La Dama Roja de El Mirón.

Wall paintings in El Castillo Cave. At 40,800 years old, probably the oldest works of art in Europe left by anatomically modern humans.

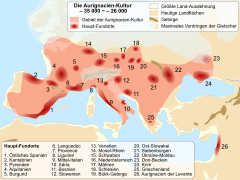

Distribution area of the Aurignacian

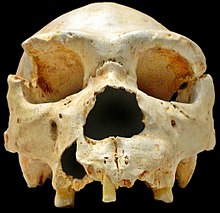

Skull of a Neanderthal man, discovered in 1848, later named Gibraltar 1. Forbes' Quarry, Gibraltar

.jpg)

Cleaver des Acheuléen, Torralba.

Skull no. 5 of Sima de los Huesos, excavated 1992

Epipaleolithic

The Mesolithic, also called Epipaleolithic in the Mediterranean region, refers to the post-glacial period up to the Neolithic (around 9600 to the middle of the 6th millennium BC). The food base changed in the wake of warming, which not only melted the glaciers but also caused the cold steppes to disappear. The large herds, especially aurochs and horses, disappeared.

To the Azilian (ca. 12.300 to 9.600 B.C.), the early Epipaleolithic, belongs as the oldest burial place the cave Los Azules in Cantabria. From the Asturian (8000-5000 BC) comes the grave from the rock overhang of Molino de Gasparín. The tibia of a red deer can be considered as grave goods there, but above all three Asturian pecks, one of which was sharpened. In contrast to these two dead men, the man of Tito Bustillo (7590-7470 B.C.) lay on his left side with bent left leg and without grave goods on the flat cave floor. Here, paint remains indicate a ritual environment.

It is recognizable that the area of burials, often used for centuries, was avoided. Personal objects increasingly served as grave goods, and there is also evidence of funerary banquets. Possibly, the long-term use of the burial sites shows a tendency towards increasing sedentariness or seasonal mobility as well as the formation of territories.

Neolithic (from 5600 BC )

The Cardial or Impresso culture spread around the western Mediterranean from the 7th millennium BC, with the exception of the Balearic Islands. The first Neolithic farmers and shepherds arrived in Andalusia from the eastern Mediterranean around 5600 BC. Einkorn and Emmer reached Spain at the latest around 5500 BC, as proved in the Coveta de l'Or and in the neighboring Cova de Cendres. However, cereals did not yet make a major contribution to the diet. Livestock farming was documented for the eastern Pyrenean foothills in the Cova Gran de Santa Linya.

Independently of this, the Meseta Neolithic developed in the hinterland. Excavations in the Ambrona area provided evidence of a fully developed early Neolithic with animal husbandry and plant cultivation for the second half of the 6th millennium BC.

The earliest Iberian Neolithic around Valencia apparently consisted of a kind of garden culture. Here, a large number of different cereals and vegetables were cultivated on small beds with the help of hoes; the villages were concentrated in river valleys, and the locations changed frequently. Besides wheat and barley, einkorn and emmer were processed. From the beginning, vegetables such as pea, seed pea, field bean, forage vetch, lentil vetch and lentil were also present. Storage tanks reached up to 100 liters in volume. Only in the Cova de les Cendres were found silos with a capacity of about 500 l.

It was not until the 5th millennium that people moved on to larger fields and the cultivation of hard and soft wheat and barley. The site of Benàmer proved that from the second half of the 5th millennium the stockpiling took on considerably larger proportions, namely up to 6000 liters capacity. Overall, the settlements became larger. Animals were increasingly kept in caves, where ritual acts can now no longer be documented.

In the 4th and 3rd millennia, supplies were no longer stored in this way, but were found around the houses. Thus, the storage of provisions was no longer regulated by the municipality, but by the household units. Their annual needs corresponded to the size of the storage vessels of about 1500 liters. At the same time, some of the storage structures, as in Missena (Valencia) or Jovades (Alicante), were in use for several millennia.

In the second half of the 3rd millennium, when the amount of rain increased again after a long drought, people again went to a diversified garden culture. Einkorn came back into use, but also new plants, such as flax. The large storage structures and settlements gave way to scattered sites, often at higher altitudes, where there is little evidence of social differentiation.

Near Antequera (Málaga) are the two Neolithic dolmens de Menga and Dolmen de Viera, dating from the middle of the 4th millennium BC, which are among several thousand such sites on the peninsula and among the largest such structures in Europe.

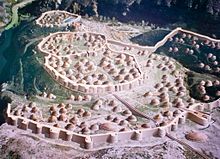

Model of Los Millares, the only site where settlement and burial ground are equally known.

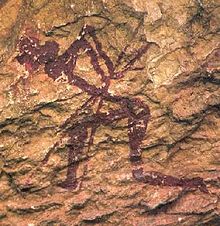

Neolithic rock drawing from the Barranco de la Valltorta (Castellón de la Plana in the region of Valencia)

Copper Age

On the peninsula, the first copper smelting is documented in the settlement of Cerro Virtud (Almería) for the first half of the 5th millennium. Nevertheless, regular copper processing may have begun much later.

Especially in the west, the Copper Age is characterized by multiple-partitioned fortifications with double-layered walls. These include Los Millares (Almería), Marroquíes Bajos (Jaén) and Valencina de la Concepción (Seville). The culture of the 3rd and early 2nd millennium BC cultivated vines and olives and produced pottery decorated with symbols, found mainly in megalithic complexes and domed tombs.

Bronze Age

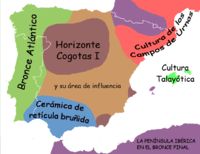

With the El-Argar culture, the Bronze Age began around 2300 BC. It existed essentially in the south. To the north, around Valencia, the Bronce Levantino joined it. In addition, the Guadalquivir culture, the Motilla culture (Motilla del Azuer) and the Tagus culture in the west of the peninsula.

El Argar is characterized by fortified settlements on high plateaus, like El Argar (Antas, near Almería), or on steep hilltops, like Fuente Alamo, not far away. Two-shelled foundation walls of rubble stone attest to rectangular, possibly two-story houses. Copper Age house types continued on the meseta. Dating of the associated Loma culture yielded values between 2250 and 1630 BC.

As early as 2000 B.C., there is evidence of pronounced deforestation in the south.

In the Balearic Islands, at the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age, there is the Talayotic culture - from the Catalan word talaia for "observation, watchtower" - a megalithic culture of the 13th to 2nd centuries B.C. Talayotic I is characterized by the emergence of water reservoirs, underground burial grounds and single towers in megalithic construction, the so-called Cyclopean technique. In the Talayotic II (from 1000 BC) walled enclosures of the settlements were added. At the latest in Talayotic III there were contacts with Greeks and Phoenicians. After 800 BC, in addition to ceramics and figurines made of bronze, objects made of lead and iron appeared. Trade with Carthaginians, who founded Ebusim (Ibis) in Ibiza around 654 BC, began. In the Talayotic period IV, from about 500 B.C., people moved to the fetal burial form. Sanctuaries were created and in the ceramics, reproductions of Carthaginian-Phoenician and Roman forms appeared.

In the 1st millennium BC, round-oval enclosures of stone ashlars appeared, enclosing some complexes. These were built around talayots, as in Capocorb Vell in the Llucmajor area. In addition, in Menorca, columns and pilasters are joined together to form regular porticoes. Taulas up to 5 meters high exist exclusively in Menorca, where 30 sites are known.

Taula of Trepucó, Menorca

_02.jpg)

The Lady of Ibiza from the Punic necropolis of Puig des Molins, possibly representing the goddess Tanit

Cultures of the End Bronze Age

Iron Age: Celts, Iberians, Phoenicians, Greeks

Phoenicians, almost exclusively from Tyros, reached the south probably as early as the 10th century B.C., without establishing settlements. Traces of early Phoenician trade contacts have been discovered in Huelva: there, imports date back to about 900 BC. Most Phoenician settlements were established from about 800 B.C. at the mouths of rivers that had now dried up and could be used to reach the hinterland, the first being in the Bay of Cádiz and near Málaga. On the settlement mound Morro de Mezquitilla (Chorreras, Algárrobo, Málaga), which was inhabited from about 650 to 450 BC, iron working could be proved for the early Phoenician period.

In the southwest, the culture of Tartessos, a port city at the mouth of the Guadalquivir River, emerged, strongly influenced by the Mediterranean. It was known in antiquity for its metal wealth. The large quantities of imported artisan goods indicate that present-day Huelva was an important Tartessian center. While in the 8th and 7th centuries the amount of Phoenician pottery was still small, it increased greatly in the 7th and 6th centuries.

Castro culture was the name given to the culture of the northwestern peninsula from the 1st millennium BC to the 1st century BC. The fortified settlements were found in an area that extended east to the Río Cares and south to the Duero River. The northern Portuguese region of Ave, located in the center of this culture, has larger castros, the citânias or cividades (from Latin civitas).

In the 7th century BC, richly furnished chariot tombs are found, such as Tomb 17 from La Joya and El Palmerón (both Huelva). Such tombs did not appear in the southeast until the 6th century. The exposed location on longer occupied mound necropolises suggests family or clan connections. Sculptures of warriors, horsemen, and lordly animals appeared in the 5th century. On the periphery of the Tartessian sphere of influence, warrior representations appeared, occasionally bearing inscriptions.

Urnfields were often considered an argument for immigration from the northeast, but this is debatable. The southeast was strongly Greek influenced from the 6th to the 2nd century BC. Phocaeans from the colony of Massilia founded Emporion, Rosas, and later Sagunt and Malaga. In the nearby oppidum of Ullastret, in addition to imported Greek pottery, a Hellenistic city wall, a sanctuary at the highest point of the hill similar to an acropolis, and an agora-like square were found. The city minted coins, however, in Punic coinage.

This phase is associated with the "Iberians", who were initially understood less archaeologically than ethnically - above all they were associated with the Catalans. From the predominantly southern Spanish core areas, their culture spread to what is now southern France. The most important inscriptions of the peninsula in Celtic language and Iberian script came from Botorrita near Saragossa. These inscriptions, about 70 in Celtic language with a total of 1000 words, were written from the 3rd to the 1st century BC.

After the First Punic War against Rome, the Carthaginians conquered the south and east from 237 BC; Cartagena was their most important base. After defeat in the second war, the Carthaginians had to vacate the peninsula in 206/205 BC.

.jpg)

... and from la Serreta (Alcoi, Alicante) with Graeco-Iberian writing

.jpg)

Lead tablet from La Bastida de les Alcuses (Moixent) with southeastern writing...

Tartessos, location and dispersion

The Lady of Elx discovered in 1897 in La Alcudia southwest of Alicante, Museu Arqueológic Nacional de Madrid

Resistance to Roman occupation (197-133 BC ).

The resistance against the occupation by Rome lasted at first from 197 to 179 B.C. After the victory of Tiberius Gracchus the Elder the revolt collapsed.

The second great revolt of the Iberians, which lasted from 154 to 133 BC, had even more serious consequences. It began with an uprising of the Beller and Avacians led by Punicus. In the same year, the Lusitanians, another Celtiberian tribe, joined the revolt. In 150 BC, a Lusitanian legation presented a truce to the Roman praetor Servius Sulpicius Galba. The latter agreed to it and even offered land to settle there. But he had the disarmed killed, and the rest were sold into slavery.

Viriathus, one of the few Lusitanians to escape being killed, led the Lusitanians from 147 and defeated the Romans in 143 and 140 B.C. In 139, the Romans broke the peace made with Viriathus and bribed his envoys, who then murdered the Lusitanian.

Decius Junius Brutus, the appointed governor of the province of Hispania Ulterior in 138 BC, had military installations built in the Tagus Valley and began to subjugate the Alentejo and Algarve regions. In the north, his troops conquered territories inhabited by the Galicians. One of the last battles may have been fought near Santarém, located in the Tejo Valley, which the Roman considered to secure access to the west coast. In 134 BC, Scipio Africanus the Younger took command of the troops. These conquered Numantia the following year. Scipio sold the population into slavery and had the city razed.

The disputes by no means ended with the subjugation. Between 96 and 94 BC, the governor of Hispania Ulterior sent troops to suppress an uprising in the northwestern part of the peninsula, which had already been occupied between the Duero and Miño rivers during the campaigns of Decius Junius Brutus. Starting in 81 B.C., revolts flared up again in the two provinces of Hispania Citerior and Ulterior, this time as a result of the weakening caused by the civil war waged in Italy.

Quintus Sertorius, who had unsuccessfully applied to be tribune of the people, now supported Gaius Marius in his fight against Sulla. The Lusitanians soon elevated him to their leader. He established a rule independent of Rome, which he defended in 79 BC. In 77 BC, Marcus Perperna joined Sertorius, who now established a counter-senate of 300 Romans and relied on the native population in addition to Romans. He resisted Pompey, who had come to Spain with 30,000 men in 76 BC. Sertorius even formed an alliance with Mithridates of Pontus in 74 BC, but he was stabbed to death at a banquet in 72 by a conspiracy headed by Perperna. Perperna, in turn, was defeated by Pompey shortly thereafter.

Only Caesar, who in 61 B.C. was in charge of the province Hispania Ulterior as propraetor, succeeded in breaking the resistance of the Lusitanian tribes, without, however, dominating the northwest of the peninsula. In order to pacify this region as well, the cities of Bracara Augusta (Braga), Lucus Augusti (Lugo) and Asturica Augusta (Astorga) were founded under Augustus. The Cantabrians around the town of Amaia were not defeated by Augustus until the Cantabrian War (29-19 BC), when they were defeated by Agrippa. Augustus made three provinces out of the previous two, Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior, by dividing Hispania Ulterior into the provinces of Lusitania and Baetica.

Urbanization, Romanization, Roman religion

The country received numerous roads and forts for military protection. Later, the dense network of roads promoted economic development. The population was Romanized, and the peninsula became a main center of Roman culture. Emperor Vespasian granted Latin citizenship to Hispania, while most provinces of the Empire did not receive Roman citizenship until 212. Open fighting occurred only when the Mauri invaded the Roman province of Baetica in 171. As a result of an administrative reform by Emperor Diocletian, two new provinces were separated from Hispania citerior, which was also called Tarraconensis after its capital Tarraco, namely the provinces Gallaecia and Carthaginiensis.

From Hispania came Emperor Trajan, as well as the families of Marcus Aurelius and Hadrian, then Theodosius I, and distinguished writers such as Seneca, Lucan and Martial.

Roman religion came to Hispania primarily in the form of the triad of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva. Mars also played an important role as a god of war in certain milieus, and the cult of the emperor was added since Augustus. In addition to the official religion, old gods continued to exist, but were given new names. The Roman gods, for their part, were modified in the new environment.

Christianization, Santiago, Arianism, Priscillianism

Christianity spread on the peninsula, despite brief but fierce persecutions, from the 3rd century until it became the predominant religion under Emperor Constantine I, and the state religion under Theodosius I.

A central role was played, although only from the early Middle Ages, by the national saint of Spain, St. James or Santiago. According to legend, Hispania was missionized by this apostle, and his body is said to have been buried in Santiago de Compostela in Galicia after 44. His tomb was "rediscovered" after 818 and King Alfonso III of Asturias (866-910) attributed his victories to the saint's intervention. It is only from the late 8th century that James is referred to as the patron and protector of Spain. The Church of Santiago claimed special authority with the tomb of the Apostle, which in turn was rejected in Toledo.

See also: History of the Jews in Spain

The Synod of Elvira, which took place between 295 and 314, was attended by 19 bishops and 24 presbyters from 37 congregations. In addition to a ban on images, it was established that Christian masters should prevent pagan cult acts by their slaves, Christians should not enter into marriages with Jews or pagans, landowners were forbidden to have their crops blessed by Jews, and believers were not to have table fellowship with them.

Missionization probably began in the cities. Tertullian claimed that Hispania was Christian as early as 202. During the persecution under Emperor Valerian, Fructuosus, the bishop of Tarraco, was executed in 259. Under Diocletian, other martyrs followed in Girona and Barcino in 304; the relics of St. Eulalia were transferred to Barcelona in the 9th century.

The bishoprics produced similarly long-lasting regional structures as the monasteries with their extensive landholdings. In particular, they became a symbol of overarching group identity and a means of politico-religious rank disputes. Bishops also intervened significantly in imperial politics, such as Constantine I's advisor, Bishop Hosius of Córdoba. He was bishop from about 296 to 357, at the same time court bishop in the emperor's retinue from 312 to 326, and an outstanding opponent of Arianism and Donatism. When Emperor Constantius II demanded that Athanasius be condemned, Hosius refused, protesting interference in the affairs of the church. In 356 he was forced to sign the Arian Confession of Sirmium, which was immediately published by the emperor as the "Confession of Hosius."

As in North Africa and other regions of the Empire, ascetic groups arose, such as that of Priscillian of Ávila († 385). Slavery, he taught, had been abolished by Jesus, equality between men and women commanded. Some of his followers were summoned to the synod in Saragossa in 380, where they were excommunicated at the instigation of Ithacius of Ossonoba. After Priscillian was nevertheless appointed bishop of Ávila in 380/381, Ithacius brought charges against him as well. As a result, Priscillian bishops were expelled from their offices by provincial officials, and finally Priscillian was executed in 385. As late as 563, the second synod of Braga felt compelled to condemn the doctrine as heresy.

Roman society and the state of late antiquity

The Roman state, except for the army and supreme jurisdiction, delegated all state functions to the approximately 2500 cities scattered throughout the empire. The total number of curials, who decided how burdens were distributed among citizens, was about 65,000 in the western empire. In the 3rd century, the tax burden was extended to all provinces, and levies were collected with increasing consistency and severity. While in the endangered areas, including Rome, the construction of theaters, baths and arenas had to take a back seat in the 3rd century in favor of city walls and other defensive structures, this was the case in Iberia much later.

80% of the population worked in agriculture. Except in Egypt, the harvests fluctuated so much that one can almost speak of shock-like jumps. Accordingly, an emperor was favored by the gods when the harvest turned out well. In southern Spain, Christians who wanted to use rituals to make their god favorable demanded that Jews not be allowed in the fields because they would spoil the effect of the rituals. The wealthy were able to stock up and thus wait for higher prices, as they occurred every year before the new harvest, and above all they were able to travel greater distances to supply cities and armies. Farmers, on the other hand, had to rely on local markets with their extreme price fluctuations. At the same time, the biggest grain traders were the emperors themselves. With the gold solidus, the borderline between the economy of the wealthy and the rest of society, which depended on bronze and silver coins, became constantly visible. The richest Roman senators had more income than entire provinces.

Below this small group, which had vast land ownership and wealth, there existed in the provinces a group of local landowners who had villae. The emperors since Constantine paved the way for them into the Roman Senate. This gave them more power and thus much greater wealth. They formed a kind of mediating class, whose members were entitled to the title vir clarissimus or femina clarissima, and who often came from established provincial families. But some families had missed out on this "post-Constantinian gold rush" and feared their relegation. The boundary line within the leadership group was the civil service with its privileges.

Imperial laws created the conditions for ceding almost unlimited powers of disposal and police to local lords, whose economic units thus became increasingly closed off from state influence. Since Constantine, lords were allowed to chain fugitive colonists who had disappeared less than thirty years before. Since 365, colonists were forbidden to dispose of their actual property, probably primarily implements of labor. Since 371 the lords were allowed to collect the dues of the colonies themselves. Finally, in 396, the cultivators lost the right to sue their lord. Under Justinian I, no distinction was made between free and unfree colonies.

The Church in Late Antiquity

Although the clergy formed a separate class, exempt from public services and personal taxation, the emperors denied it access to the upper classes of society. Moreover, this generated resistance among the curates, who were not exempt from duties, because the more members of a community were exempt from duties, the higher the burden became on the rest.

The congregation of these 4th century clerics was by no means composed of the poor and marginalized of society. Recent research shows that the members of the congregations were artisans and civil servants, artists and merchants. They occasionally referred to themselves as "mediocres," who were neither rich nor poor.

Income from the congregation and the care of the poor earned the church state privileges. A privilege of 329 explicitly explains that the clergy should be there for the poor, while the wealthy, which did not include the clergy, should go about their business. However, leading members of society who became Christians, displacing long-time fellow members of the community, were soon able to rise in a single move rather than over long periods of training and experience. Ambrose of Milan was thus able to become a bishop immediately.

The administrative division of the Imperium Romanum around 400

Ruins of the Basilica of Empúries in Catalonia

Alfonso III with his wife Jimena and Bishop Gomelo of Oviedo, 10th century ms., Oviedo Cathedral Archives.

Baptistery with baptismal font in the basilica of Son Peretó

The Roman aqueduct in Segovia

Cantabrian territory

Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, 218-19 BC.

Migration of peoples, Suebi, Vandals, Visigoths

→ Main article: Migration of peoples

Vandals, Alans and Suebi crossed the Pyrenees in 409. When Vandals and Alans moved on and conquered Carthage, even Roman naval supremacy was challenged. In 455 the Vandals sacked Rome, as the Goths had done in 410. The Suebi were the only Germanic tribes left in Hispania, while Rome lost its last bastion in Tarraco in 472. Italy was occupied by the Ostrogoths from 489, while the Visigoths had gained independence in Gaul.

Suebi Empire in the Northwest (409-585)

→ Main article: Kingdom of the Suebi

The core territory of the Suebi was between the Duero and the Ría de Vigo. With the foundation of the monastery of Dumio, monasticism was promoted, which later took off enormously. In this process, the rulebook of the Benedictines became less central than the work of Fructuosus of Braga († 665), but also Isidore of Seville.

In Hispania they were assigned the province of Gallaecia, but in 418 the Vandals almost destroyed them along with their allied provincial Roman troops in the Battle of the Nervasos Mountains. In 429 Vandals and Alans left the peninsula and went to North Africa to conquer Carthage in 439. The Suebi under their first king Hermericus († 441) were the only ones to remain in the country. His son Rechila (438-448) succeeded in conquering Baetica. In 440 the king received an imperial envoy in Mértola. In the following years, Roman troops, supported by Visigoths, fought Bagudean rebellions in the Ebro Valley. Rechila's Catholic son and successor Rechiar married a daughter of the Visigoth king in 449, advanced into Basque territories, and threatened Saragossa. When the Suebi advanced into Tarraconensis in violation of the treaty, Rome asked the Visigoths to move to Hispania. Their king, Theoderic II, was victorious at Órbigo near present-day Astorga. Braga was sacked on October 28, 456, and King Rechiar was executed. Visigothic garrisons were temporarily installed in Suebian territory. The Visigoths concluded a new treaty with Emperor Majorian.

The northwestern Suebi had appointed an otherwise elusive Malchras as their king in 456, while in the capital Braga successively Aiulf (456 to June 457), who may have dared to revolt, and Framta (457-458) ruled in dependence on the Visigoths. Soon the Northwest Suebi joined Maldras' son Remismund. Maldras attacked cities far to the south, such as Lisbon in 457 or Porto the following year. Now Remismund was forced by the Visigoth king Eurich to recognize his suzerainty. He converted to Arian Christianity. Since Hydatius, the author of the chronicle named after him, died in 470, we are exceedingly poorly informed about the second kingdom of the Suebi.

Unlike the Visigoths, the Suebi converted from Arianism to Catholicism shortly after 550. However, Martin of Braga, with De correctione rusticorum, fought their religious ideas, which rather formed a syncretism of pagan and Christian ideas. Nevertheless, as evidenced by the Parochiale of 572, the Suebi succeeded not only in establishing a monastic landscape, but also in imposing a parish structure. Only a few examples of their church architecture have survived, such as in Egitania or in Torre de Palma.

In 573, the Suebi under King Miro supported the rebellious Hermenegild, who besieged Seville. After all, this support of the eldest son could be the reason why the Suebi were subjugated by the Visigoths in 585.

Visigothic Empire (until 711)

Eurich dissolved the federative relationship with Rome and extended the empire to the Loire and far into Hispania. In 475, he made peace with Emperor Julius Nepos, who recognized his independence. The Visigoths initially confined themselves in the south to important bases such as Mérida. It was not until the nineties of the 5th century that several waves of settlements occurred. The population of their empire is estimated at perhaps 10 million. In 507, the Frankish king Clovis defeated the Visigoths under Alaric II, the son of Eurich, at the Battle of Vouillé.

Probably introduced around 475, the Codex Euricianus, a law code named after King Eurich, was the first legal codification of a Germanic empire. It became the basis for the later legislation of Visigothic rulers. The code contained the law of the Visigoths tied to ethnicity rather than residence, while the law of the Romance population was codified in the Lex Romana Visigothorum. This was put into force in 506. It is a revision of the Codex Theodosianus, an influential Roman law collection.

According to older research, the Goths received two-thirds, the Romans the rest of the cultivated land, but two-thirds of the labor force. However, apparently there were still wealthy landowners in the Tolosan Empire who had themselves protected by armed men and fortified their country estates. Many provisions of the Codex Euricianus deal with freemen, whose numbers were apparently considerable. The retinues consisted partly of freemen and partly of unfree men. Simple freemen apparently often found themselves in dire straits, as evidenced by provisions in the Codex dealing with the self-sale of freemen and the sale of freemen as slaves against their will. After 507, settlement centers emerged in Septimania, but also around Segovia, Madrid, Palencia, Burgos, where the row tombs there are attributed to them. In Andalusia, Gothic names appear in inscriptions, especially around Córdoba and Mérida. The Ostrogoths expelled Gesalech, the illegitimate son and successor of King Alaric II, who died in 507, and their king Theoderic took over the rule in the Visigothic Empire, where he ruled until 526.

In 507, Romans of senatorial origin fought with the Visigoths against Clovis' Franks. In administration, too, the highest offices were accessible to the Romans. Although they had to pay taxes, unlike the Goths, their tax burden was much lower than in the Roman Empire. The kings had a knowledge of Latin at least since Theoderic II; at Eurich's court there was interest in Latin poetry.

Estimates of the number of Visigoths living in the Tolosan Empire, especially around Toulouse, vary between 70,000 and 200,000, or about one to two percent of the total population. Marriages between Goths and Romans remained forbidden until the end of the 6th century, because while the Romans were Catholics, the Goths were Arians. Eurich forbade Catholics to fill vacant bishoprics. He saw especially in the bishops potential allies of the emperor. Alaric II, on the other hand, adopted a pro-Catholic course. He incorporated into his Lex Romana Visigothorum provisions of Roman law that regulated the position of the Catholic Church, but not a law of Emperor Valentinian III. which subordinated the Gallic church to the pope.

After 526, the Visigoths made themselves independent again under Amalaric, but his troops suffered a defeat at Narbonne in 531 against the Frankish king Theuderic I. After the destruction of the Vandal kingdom by an army of Emperor Justinian, an Eastern Roman attack also threatened. In the first battles with the Eastern Romans around the city of Ceuta, the imperial troops were victorious. Assassinations, rebellions and coups d'état were so frequent in the following period that the Frankish chronicler Pseudo-Fredegar coined the term "morbus Gothicus" for them. One of the rebellions provided the Eastern Romans with the pretext to intervene; in 552, as allies of a Visigothic rebel, they landed on the southern coast and occupied an area that stretched at least from Cartagena to Málaga.

Under King Leovigild (568/9-586) the empire expanded against the Cantabrians, the Sappi in the Salamanca area, Aragonese and Basques. He was able to push back the Eastern Romans, subduing the Suebi in 585. A Frankish attack on Septimania was repulsed, the rebellion of Leovigild's son Hermenegild put down, who fled to the eastern Roman city of Córdoba in 582 after establishing contacts with Constantinople and renouncing Arianism - Pope Gregory I even called him a martyr. Leovigild's attempt to resolve the tensions between Arians and Catholics failed.

An important concern was the "imperialization" of the kingship by imitating the emperorship. The image of the emperor now no longer appeared on the gold coins, the king wore the crown and purple instead, and after the manner of the emperors he founded a new city, which he named Reccared Recopolis after his son. In addition, from about 569, the focus of the empire shifted to Toledo. In this empire, besides 100,000 Goths, about 9 million Romans are said to have lived. Until the end of the empire, however, the kings were able to achieve only temporary successes against the Basques.

Leovigild's son and successor Rekkared I (586-601) was able to end the war against the Franks. He converted from Arianism to Catholicism in 587. The 3rd Council of Toledo ended the religious conflicts. Among the council's decisions were measures against the Jews. They were forbidden to marry Christian women or have Christian concubines. In 694, drastic decisions were made at the 17th Council of Toledo, encouraged by the rumor that Jews had made contacts with the Muslims of Syria or even planned a conspiracy. The king demanded expulsion from his kingdom. Children from the already existing connections had to be baptized, and from the age of 7 children from Jewish families were to be given to Christian ones. Slaves of the Jews were to be set free. Formally, the king presided over the council, but the contents were probably contributed by Bishop Leander of Seville and Abbot Eutropius of Servitanum. Some Arians went to Africa, and there was a rebellion in Mérida. In 633, the 4th Council of Toledo adopted the Old Spanish liturgy, which exercised great influence until the 11th century.

Rekkared's son Liuva II was deprived of power in 603 after only one and a half years of rule; a conspiracy of nobles brought his successor Witterich to power. This ended the dynasty founded by Leovigild and the principle of elective monarchy reasserted itself. Despite the unstable conditions, King Suinthila succeeded in occupying the last Eastern Roman bases around 625.

A reaction of the royalty to the superiority of the nobility came under Chindaswinth. He himself had come to the throne in 642 through a coup d'état and he wanted to enforce the replacement of the nobility by reliable followers. He even succeeded in 653 in securing the succession for his son Rekkeswinth, whom he elevated to co-ruler in 649.

But after Rekkeswinth's death there was another royal election in 672; the probably 90-year-old nobleman Wamba was elevated to king. He is the first ruler for whom an anointing according to the Old Testament model is attested. However, the almost centenarian was forced to abdicate in 680. The unreliability of the army had already become apparent in the Septimania uprising ten years earlier. Its commander Paul had rebelled against Wamba and mocked him in a letter. His own men plundered and raped, whereupon the king had the offenders circumcised to symbolically expel them from the Christian community. Epidemics broke out in 693/694 and again in 701, causing a significant decline in population. Eventually, the number of royal families was reduced to two, both of them descended from Chindasvinth.

King Rekkeswinth issued a uniform code of law for Goths and Romans (Liber iudiciorum) in 654. This idea represented a pioneering achievement of the Visigoths, because in the other Germanic kingdoms the ethnic principle still prevailed. A division of the empire among the sons of a deceased ruler, as was common among the Franks and Burgundians for a long time, was out of the question for the Visigoths. Prominent metropolitans such as Isidore of Seville and Julian of Toledo - one of Romanesque, the other of Jewish origin - became propagandists of the imperial idea to which loyalty was owed.

Kings interfered in ecclesiastical affairs, but so did bishops in politics. Thus, bishops, as participants in councils, passed resolutions on how to proceed in the election of kings. They also assumed ex officio duties in the judiciary and in tax collection; the church was treated as a branch of the imperial administration.

The court nobility came to the fore, and from 653 only maiores palatii and bishops were allowed to participate in the election of the king, whereas until then this right had been granted to all nobles. However, not only the maiores palatii, but all free inhabitants of the realm were sworn in to the king. His followers were bound to him by an oath of their own. The king lent them lands, but reserved the right to revoke these loans at any time. In 683, the 13th Council of Toledo decreed that no court noble could be condemned without a trial; a tribunal of bishops and court nobles was responsible for such proceedings.

Most of the army consisted of freemen, whose number dwindled in the 7th century, although the kings tried to strengthen them with their legislation. The nobles equipped only a small part of their unfree and led them into battle. King Wamba threatened drastic property and liberty penalties for failure to fulfill their duties.

A very rich upper class, whose fortune consisted mainly of land ownership, was opposed by a large number of unfree and freedmen. Episcopal churches, monasteries and parish churches owned numerous slaves. It happened so often that bishops had their church slaves mutilated as punishment that councils felt compelled to prohibit this by appropriate regulations. Slaves often escaped from their masters, creating a shortage of labor. The manor was often worked by servi, while other plots were given to peasants of various degrees of freedom. An approach to a landlord mode of production can thus be recognized.

The process of de-urbanization continued. Crafts and metal extraction also declined. Greek, Jewish and merchants from the Mediterranean region further east conducted foreign trade. At least, it was the custom in Mérida for Greek merchants to go first to the bishop, so that a certain continuity and regularity can be assumed here. Money, which was minted mainly in the north, was used to pay the army, rather than for commercial needs. At times even gold coins were issued. The lion's share, however, was tremisis (triens).

After the death of King Witiza (710), two rival factions from the families of Chindasvinth and Wamba fought over the succession. Finally, Roderich was enthroned against the opposition of Witiza's supporters, who installed Agila II. (711-714) were enthroned.

In the spring of 711, a relatively small force consisting of Arabs and - predominantly - Berbers crossed the Strait of Gibraltar. Roderich, who had just fought the Basques, suffered a crushing defeat in the Battle of the Río Guadalete in July 711. Visigoths continued to resist in the Tarraconensis region until 719, and in Septimania until 725, but practically the entire peninsula fell to the conquerors.

Depiction of an artichoke in the Rylands Haggadah (narrative and instructions for the Seder on Erev Pesach, the eve of the festival of the liberation of the Israelites from Egyptian slavery). The manuscript was named after the John Rylands Library in Manchester.

Western Gothic bow brooch of the 6th century from Castiltierra (Segovia province)

Crown of Rekkeswinth (653-672)

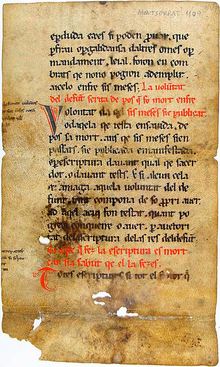

Fragment of a Catalan version of the Visigothic Liber Iudiciorum, Biblioteca de l'Abadia de Montserrat, Ms. 1109, end of the 12th century.

The Iberian Peninsula in 586

Development of the Visigoth Empire. Red: Settlement of Visigoths in Aquitaine from 418. Light orange and orange: expansion until 507. Orange: Visigoth Empire (with Septimania) between 507 and 552. Green: Suebi Empire, which belonged to the Visigoth Empire from 585 onwards

Idanha-a-Velha Cathedral

Empire of the Suebi around 455

Europe with the main migratory movements

Islamic Empires (711-1492)

The inner-Islamic conflicts were of considerably greater importance than the conflicts with groups of other faiths, because since Muhammad the conquerors monopolized political and military power and offered protection, for which the rest of the population raised the necessary taxes through economic activity. The central power was only able to suppress centrifugal tendencies temporarily and with great harshness. This was due to the fact that the Berbers of northwestern Africa were attracted to a direction of Islam that demanded the equality of all Muslims, regardless of the question of ethnic origin. They thus resisted the Arabs, who claimed permanent superiority. The dynasty that ruled most of the peninsula from 756 onward was based, on the one hand, quite predominantly on Berbers, and on the other hand, it encouraged independence movements among the North African Berbers in order to maintain a buffer zone against the greater Arab empire. Against this background, cultural superiority, reflected in art and architecture, was a means of gaining prestige and competing with the center of the great empire, Damascus. The claim to the caliphate, which divided the Islamic world even more clearly from 929 onward, is in line with this.

After the fragmentation of this caliphate into small dominions around 1031, strictly religious groups proselytizing with the sword intervened with considerable violence in the internal Islamic conflicts and those with neighboring Christian states. On the other hand, the Muslim part was heavily involved in the struggles between the three major mountain groups.

Conquest by the Islamic world empire (from 711)

Count Julian of Ceuta, an opponent of King Roderic, apparently made contact with the Muslims. Musa ibn Nusayr, governor of the caliph, sent out about 500 men under Tarif ibn Malik on a raid in 710. In 711, an army consisting mainly of Berbers and numbering about 7000 men landed at Gibraltar under Tariq ibn Ziyad. Tariq defeated the Visigoths on July 19 in the Battle of the Guadalete River and occupied the capital Toledo. In June 712, Musa landed with a conquering army of 18,000 men from the east of the empire, composed of Arabs and Berbers, and together with Tariq continued the conquest.

Abd al-Aziz, Musa's son, was appointed governor of al-Andalus, as the new masters called the peninsula, with Seville as its capital in 714. His attempt to establish an independent rule led to his assassination in 716. His successor Ayyub made Córdoba the capital. The governor Samh (718-721) occupied Barcelona in 720 and crossed the Pyrenees for the first time.

However, in 718 began in Asturias the revolt of the Visigoth Pelayo (Pelagius), who had himself elected king. This led, if we follow the unreliable chronicle, to the foundation of the Kingdom of Asturias, which was stabilized by his son-in-law Alfonso I of Cantabria (739-757). At the same time, the siege of Constantinople (717-718), carried out with the deployment of considerable forces, failed, ultimately breaking the seemingly unstoppable expansionist power of the Islamic empire. In the Maghreb, rebel Berbers under Maysara defeated an army brought over from Andalusia, and in 740 an army coming from the east, and Maysara even assumed the title of caliph. The Berbers of the Iberian Peninsula drove the Arabs there southward. Although the rebels were defeated, the victory was short-lived.

In the north, development was more dominated by non-Muslim groups, less by internal Islamic conflicts. After a Muslim army failed to break Asturian resistance at the Battle of Covadonga in 718 or 722, Muslim raids continued into Aquitaine, Provence, and Burgundy in 725. In 732, an army captured Arles and Bordeaux. But as it moved further north, the Battle of Tours and Poitiers occurred against Frankish forces under Charles Martell. Abd ar-Rahman was killed in the battle and his army retreated. Thus, at first, the power of expansion also slackened at this point. But it was not until the Berber uprisings and the breakup of the world empire that it finally came to a halt here.

In 741, an entire Arab army moved into the peninsula under Balğ ibn Bišr, who had defeated the Berbers with his troops and who rose to the governorship in 742. As in other provinces, this was an expression of unrest, mainly due to disputes between northern and southern Arabs, but also between the governors residing in Córdoba since 716 and their commander-in-chief in Kairuan, Tunisia.

Independence from the Islamic Empire, Emirate of Córdoba (750-929)

Fall of the Umayyads in the east, independence of al-Andalus

The Christian population dominated trade, while the conquerors skimmed off some of the profits. Foreign contacts were also largely handled by Christians, if only because of their language skills.

In addition, the Berbers, who had mainly borne the conquest of the Visigoth Empire, felt disadvantaged, since they were denied settlement in the fertile south and deported to the north for border defense. As in the western Maghreb, this disadvantage of the Berbers in Andalusia led to a rebellion (741-746) that could only be suppressed by sending an Arab army from Syria.

The governor of Narbonne, Yusuf ibn Abd ar-Rahman al-Fihri, who was responsible for al-Andalus from 747 to 756, made himself virtually independent under the impact of the fighting between the Umayyads and the Abbasids, which ended in a massacre of the Umayyad family in 750. He led a punitive expedition against the Basques in Pamplona in 755, but it failed.

Takeover by Abd ar-Rahman (756), conflicts with Franks and Asturias

The formation of a dynasty was prevented by the arrival of the last Umayyad Abd ar-Rahman I, who had escaped the massacre of his family. He had fled to the Maghreb, where he found support among the Berber tribe from which his mother was descended. With the latter, he defeated al-Fihri in the Battle of Musarah near Cordoba in May 756.

Abd ar-Rahman founded the Emirate of Córdoba. An Abbasid force was defeated, and by 760 he was the undisputed ruler of al-Andalus. But several Berber revolts (766-776) revealed the fractiousness of the empire. Unlike the Arabs, the majority of Berbers had converted to Ibadiyya, a Kharijite form of Islam.

Abd ar-Rahman I, who supported the rebellions in the Abbasid Empire, divided Andalusia proper into provinces. In central Spain, the margravates of Mérida, Toledo and Saragossa were created. There, families ruled, some of them quite independently from Córdoba. Thus, Zaragoza and the Ebro Basin were ruled by the Banu Qasi until 907.

In 777, rebels of the Fihri clan appeared at the Diet of Paderborn and asked Charlemagne for support. In 778 Charlemagne crossed the Pyrenees and took Pamplona, but failed to conquer Saragossa. On the way back, he suffered a legendary defeat at the Battle of Roncesvalles. In turn, the Muslims took Narbonne in 795, the Franks conquered Barcelona in 801, and Tortosa in 811.

Under Abd ar-Rahman, increased immigration of Arabs from Syria began, which significantly accelerated cultural Arabization. In order to symbolically underpin his ruling power, as well as his ethno-religious orientation, he began extensive building activity. In addition to the fortification of Córdoba, he built the Palace ar-Ruzafa and began the construction of the Great Mosque. The development of agriculture was promoted by irrigation and canal construction techniques. This led to the rise of the peasant middle and small estates and became the basis for economic expansion.

Intra-dynastic conflicts, revolts and expulsions

After Abd ar-Rahman's death, he was succeeded in 788 by his second son, Hisham I, who prevailed over his brothers. In 791 he moved to Old Castile, his army defeated Bermudo I of Asturias further west, and then drove the Franks from Girona and Narbonne in 793, and then moved across the Pyrenees to Septimania, where they defeated an army of Franks. However, intra-family conflicts and rebellions put Hisham on the defensive, so that even the Balearic Islands were contested between Muslims and Franks from 798. Under Hisham, the Malikite school of law began to spread, and with it one of the four schools of law of Sunni Islam.

In 796, al-Ḥakam I. (until 822) succeeded his father. However, two uncles of the new emir disputed his power and moved Charles to a new campaign. King Alfonso II of Asturias pledged support. Involved was Charles' son Louis the Pious, who with his army sacked the cities of Lleida and Huesca in 800 and occupied Barcelona in 803. The count there took the title of Margrave of Gothia. Subsequently, al-Ḥakam and Charles concluded a truce, the uncles had been given the eastern part of the emirate between Huesca and Murcia in a settlement.

Subsequently, al-Hakam suppressed autonomy efforts in the provinces, especially in the margraviate. In Toledo, for example, 5000 nobles are said to have been murdered on his behalf at a banquet in the Alcázar in 797. He built up a mercenary army of Berbers, Franks and Slavic slaves. With their help, a conspiracy in Córdoba was put down in 805 and an uprising in its suburbs in 818. The suburb on the other side of the Guadalquivir was destroyed and the population expelled. Many of its opponents then fled to the Idrisids of Morocco, who settled the Andalusians in Fez. The remaining families, reportedly 15,000 of the total 20,000 expelled, temporarily took power in Alexandria, Egypt (until 825), before conquering Crete in 827 and establishing an emirate that lasted until 961. The distrustful emir surrounded himself with a bodyguard from outside the country ("the Silent Ones"), who were subordinate to the head of the Christian community.

Artistic flowering, Viking campaign (844), dominance of Asturias, Mozarab revolts (about 866 to 928)

Hakam was succeeded in 822 by Abd ar-Rahman II, whose reign was marked by literary and artistic activity. Arabic prevailed over Romance, encouraged by immigration.

Although there were battles in the northern border areas, in general the conflicts were managed without open warfare. However, in 842 the important Marquisate of Saragossa declared itself independent, and in 844 Vikings appeared at the mouth of the Tagus River and also reached Cadiz. From there they sacked Seville, but were then defeated by troops of Abd ar-Rahman. In 859, the Vikings again raided in Hispania.

Large sections of the Mozarabians had come to terms with Islam, especially the advocates of Adoptianism, among whom Bishop Elipanus of Toledo, who was still Primate of Hispania, played a leading role. A group of Christians of Cordoba, on the other hand, reviled Muhammad and Islam in 851 and 859, for which the courts passed 45 death sentences (Martyrs of Cordoba).

Since the margraviate of Toledo declared its independence in 852 and Mérida in 868, Muhammad could not prevent Alfonso III of Asturias from expanding his empire. On the contrary, in 883, after Alfonso had allied himself with Ibn Marwan of Mérida, he was forced to make peace with Asturias. The emirate was in danger of disintegrating when, in 884, the rebellion of Umar ibn Hafsun began in Bobastro, who ruled the provinces of Málaga and Granada and who established links with the insurgents in Jaén. He relied mainly on Berbers and Mozarabs. In 888, the emir's son and successor, al-Mundhir, died before Bobastro. His brother Abdallah continued the struggle, but Murcia and Valencia were lost in 889, and other members of the Umayyad clan made themselves independent in Ronda and Seville. Umar ibn Hafsun had to be recognized as governor in Granada, and in 895 a son of the emir revolted, leaving Abdallah temporarily in control only of the environs of Cordoba. The nadir of his rule was reached when, around 900, Abdallah had to recognize the suzerainty of Asturias over all of Iberia. However, this led to opposition from the Muslim clergy, who accused the emir of being the vassal of a Christian king.

Umar ibn Hafsun eventually established contacts with the Aghlabids and later the Shiite Fatimids in North Africa. When he converted to Christianity, however, he lost many allies. Abdallah now increasingly succeeded in playing the insurgents off against each other. When he was finally able to ally himself with the Banu Khaldun, Umar ibn Hafsun was largely isolated.

The Emir's grandson, Abd ar-Rahman III, succeeded in winning Seville in 913. But it was not until the death of Umar ibn Hafsun that he gained the upper hand. In addition, the outbreak of a civil war in the kingdom of León beginning in 925 weakened the Muslim insurgents in the margraviate, who were supported by León. In 927, the Hafsunids were forced to capitulate, as were the Marwanids of Merida. With the conquest of Toledo, the fighting that had lasted for a human lifetime ended around 930, in which both Christians and Shiite Fatimids had intervened, but which had been carried mainly by Mozarabs.

Caliphate of Córdoba (929-1031)

Sunni supremacy, struggle against Shiites and Christians

Abd ar-Rahman III assumed the title of caliph on January 16, 929, to counter the claim of the Fatimids of North Africa, who were also caliphs but were Shiites. His fleet occupied Melilla in 927 and Ceuta and Tangier in 931. Furthermore, alliances with the Berber Banu Ifran or Magrawa as well as with the Salihids prevented further Fatimid expansion in Morocco.

'Abd ar-Rahman also won a victory against León and Navarre in 920. However, he suffered a defeat against León in the Battle of Simancas in 939, narrowly escaping capture. The betrayal of fellow Arabs caused him to rely more heavily on Berbers from then on. Finally, in 951, he was able to impose Umayyad suzerainty over León, Castile and Barcelona, which led to substantial tribute payments.

Cultural and economic flourishing, Islamization

At the same time, art and science reached their highest flowering. The population grew rapidly. Cordoba had 113,000 houses and 600 mosques and magnificent palaces, including the Alcázar. Córdoba eventually became the largest and wealthiest city in Europe, ahead of Constantinople, with a population of perhaps 500,000.

At the same time, Islamization took hold of the leadership groups who owed their fortunes and careers to the court. Then came the cities, which were now more strongly influenced by Muslim architecture and economy. The rural areas, on the other hand, were not more strongly affected until very late, in many cases not until the 12th century. Many African and Middle Eastern techniques and products were transferred to Spain, where figs and dates became naturalized, while domestic pigs disappeared and more goats and sheep were kept instead.

His son al-Hakam II (961-976), known as a poet and scholar, ruled in the same spirit as Abd ar-Rahman III, whereas under Hisham II (976-1013) the caliphate lost its importance. Al-Hakam promoted economic development by expanding irrigation systems, roads and establishing markets. The promotion of art and culture was of great importance to him. Thus, a library with 400,000 volumes was built in Cordoba, but it was lost toward the end of the caliphate.

While internal administration was largely left to the vizier al-Mushafi, General Ghalib gained considerable influence. He was primarily concerned with repelling the last Norman attacks in 966 and 971, but above all with the battles with the Fatimids and Zirids, respectively, in northern Morocco. The latter were defeated by Ghalib in Morocco in 974. In the face of the Christian empires of Navarre, Castile and León, al-Hakam was able to assert the supremacy of the caliphate. Hisham II succeeded him in 976 at the age of ten. His mother Subh and Jafar al-Mushafi, the first minister, exercised the regency for him.

Beginning disempowerment of the dynasty, influence of the Berbers

Militarily, the Caliphate reached its greatest power at the turn of the millennium thanks to Almansor, a minister and general of Hisham. In 985, Barcelona was taken, while in the same year the Fatimids abandoned their plan to conquer Morocco; at the same time, the flight of the Zanata Berbers to Iberia, who had been defeated, continued. The triumphant march of the Sunnis began. Subh promoted Almansor and appointed him chamberlain. By 978, he had also prevailed over General Ghalib. Hisham was ousted from government, and in 997 he had to give Almansor sole rule. After the latter's death, his son Abd al-Malik (1002-1008) came to the throne, consolidating his position in the empire through wars against Navarre and Barcelona, but was assassinated by Abd ar-Rahman Sanchuelo. When the latter was in turn overthrown in 1009 by a popular uprising under Muhammad II al-Mahdi, the rebels simultaneously deposed Hisham II.

Sulaiman, as the great-grandson of Abd ar-Rahman III, was installed as caliph by Berber forces in 1009. Although they were able to hold their own against the troops of Muhammad and the Catalans allied with him, Sulaiman gave up the battle prematurely, so that Córdoba was sacked again, this time by the Catalans. In 1013, Sulaiman regained the caliph's throne after Córdoba was again conquered by the Berbers and after Hisham was deposed until 1016. Now the Zirids of Granada formed an independent Berber dynasty (1012-1090). Sulaiman finally fell into the hands of the Hammudids of Malaga and Algeciras (1016-1058) in 1016 and was executed. The title of caliph thus passed from the Umayyads to the Hammudids under Ali ibn Hammud al-Nasir (1016-1018). With him, a non-Umayyad and at the same time an Idrisid descendant came to the throne for the first time in 1014, followed by his brother after his assassination in 1016.

Small states (Taifa kingdoms) (from 1031), supremacy of Castile (until 1086)

Between 1009 and 1031, resistance from the regions increased under the leadership of locally based families, but also at court. In the course of the struggles between the various ethnic groups, first and foremost the Berbers who had migrated from North Africa as mercenaries in the second half of the 10th century and the long-established "Arab" population, which was primarily the descendants of the mostly Berber conquerors of the 8th century and the Hispano-Romans (Muladíes) who had converted to Islam, the individual parts of the empire became independent under new dynasties. Initially, up to 30 taifas emerged, which fought each other in shifting alliances.

These taifas can be divided into three groups, the taifas of the Berbers, who initially placed themselves under the spiritual leadership of the Hammudids of Malaga and the military leadership of the Zirids of Granada, the taifas of the Arabs and muladíes, and the taifas of the Amirids, descendants or ṣaqāliba (that is, Slavs and other light-skinned and reddish peoples) of Almansor. The latter, however, were unable to found a dynasty because the former generals and officials were often eunuchs. An exception was Muğāhid of Dāniya, who founded a dynasty with his Christian wife in the Gulf of Valencia and the Balearic Islands.

Under Abbadid pressure, the smaller taifas of the Zanata were increasingly weakened, so that Granada quickly became the most important taifa of the Berbers. Eventually, the Zirids also got rid of the Hammudid caliphs of Malaga and Algeciras. Of the Arab taifas, the most important were Seville, Zaragoza, Badajoz, Córdoba and Toledo, some of which also subordinated themselves in a legitimist manner to a shadow caliphate. The most important dynasties of this period were the Hūdids of Zaragoza, the 'Abbādids of Seville, the Afṭasids of Badajoz, the Dhun-Nunids of Toledo, the Hammudids of Malaga, the Jahwarids of Córdoba, and the Zirids of Granada. The Amirids ruled the eastern coast between Almería and Valencia.

Although the Abbadids of Seville soon rose to become the most powerful kingdom, they too had to recognize the suzerainty of Castile in 1064. When Alfonso VI of Castile conquered Toledo in 1085, then occupied Aledo Castle far to the south, the petty kings turned to the Almoravids of Morocco for help. The latter defeated the Castilians in 1086 at the Battle of Zallaqa, near Badajoz.

Meanwhile, there was a renewed cultural flowering, especially in the fields of poetry, art and science. The important historians al-Udri (1002-1085) and Ibn Hayya (987-1076) lived in this period, as did the geographer al-Bakri († 1094). The lexicographer Ibn Sida (1007-1066) of Murcia wrote two dictionaries, and among the physicians Abu l-Qasim az-Zahrawi († 1010; Latinized Abulcasis) became famous for his textbook of surgery, the Kitab al-Tasrif, which was translated into Latin by Gerhard of Cremona (1114-1187). Among astronomers, it is worth mentioning az-Zarqala († 1087) of Toledo, who also became known in Christian Europe under the name Azarquiel. Other important men were the polymath Ibn Hazm (994-1064), the poet Ibn Zaidun (1003-1071), and the poet and philosopher Ibn Gabirol (c. 1021 to c. 1058). The most important figure was Ibn Hazm al-Andalusi. He was born in Córdoba, and his family was probably of Visigothic descent. He rose to become a polymath, extensively versed in theology, philosophy, and poetry, but as a follower of the Zahirite school of law, he was banned from teaching in the Great Mosque; in Seville, his works were burned. Another reason for his repeated banishment was his alleged pro-Umayyad stance. His work The Separation between Religious Communities achieved great importance. In it, he sought to refute Judaism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism, as well as the main Islamic sects. Also, a tract he wrote on love, The Collar of the Dove, was widely read.

Almoravids (from 1085), second Taifa period (from 1144), Almohads (until 1212)

In 1086, the Almoravids achieved a decisive victory that opened the Iberian Peninsula to them. In 1091, Seville fell. The Almoravids took control of al-Andalus, which now became part of an empire centered in northwest Africa.

Outraged by the "decadent" lifestyle and the "softening" of the religion they found, they began the subjugation of the Taifa kingdoms in agreement with jurists who highlighted the failure of the petty kings to protect Islam. This ended in 1110 with the fall of the Hudids of Saragossa. Finally, when in 1153 Ramon Berenguer IV. (r. 1131-1162) conquered the viceroyalty of Siurana in Catalonia, the last Taifa kingdom in the northern part of the peninsula had also disappeared.

Episode remained only El Cid, a disgraced vassal named Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar (c. 1043-1099), whom his Muslim followers called sid (lord). At first he supported the King of Saragossa against the Marquis of Barcelona, but above all, in a legendary move in 1094, he conquered the kingdom of Valencia, where he remained until his death in 1099.

Under Ali ibn Yusuf, Valencia and Saragossa, as well as the Balearic Islands, were subdued, but Saragossa was lost to Aragon in 1118. Most importantly, a new reformist power, led by Zanata Almohads, conquered the Almoravid Empire in Morocco. After the death of Ali ibn Yusuf, the Almoravids were forced to withdraw from Andalusia, which favored the rise of Ibn Mardanīsh (1143-1172) of Valencia. The dynasty ended with the storming of Marrakech by the Almohads in 1147 and the death of the last Almoravid.

The second Taifa period began in 1144, when their empire collapsed. An equally strict religious reform movement followed with the Almohads. They conquered Valencia in 1172, but an attack on Lisbon failed in 1184. After their victory at Alarcos in 1195, they were finally defeated by the army of the kingdoms of Portugal, Castile, Navarre and Aragon at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa on July 16, 1212. With Ibn Hud († 1238) and the Nazarites, Andalusian Muslims again came to rule.

Emirate of Granada (1232-1492)

But al-Andalus was limited to the Emirate of Granada under the Nasrids. The dynasty dates back to the Arab Muhammad Yusuf ben Nasri 'Alhamar' ('Redbeard'), who was proclaimed Sultan in 1232. In 1234 he declared himself a vassal of Cordoba, but Ferdinand III conquered the city and Muhammad then seized Granada; for this he was enfeoffed by Ferdinand in 1236. In 1238 he entered Granada to occupy the Palace of the Windcock (the old Alhambra). Muhammad soon had to pay homage to him and recognize him as lord.

Under Muhammad II al-Faqih (1272-1302), the Merinids of Morocco gained supremacy over the Nazarites, but in 1340 they were defeated at the Battle of Salado by a fleet led by the Castilians. From then on, the Muslims no longer received support from North Africa. Economically, Granada fell into dependence on Aragon and Genoa, which controlled foreign trade.

Under Yusuf I. (1333-1354) and Muhammad V. (1354-1359), culture and economy flourished again. Granada was expanded and palaces were built in the Alhambra, including the Court of the Lions. The war for Granada was started jointly by Ferdinand V and Isabella I in 1482, while Granada experienced a civil war. The last emir Muhammad XII "Boabdil" surrendered in 1492.

The Nasrid Kingdom of Granada

Pavilion in the Lion Court of the Alhambra

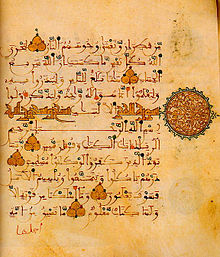

Koran from al-Andalus, 12th century

Almoravid Empire in Morocco and Spain

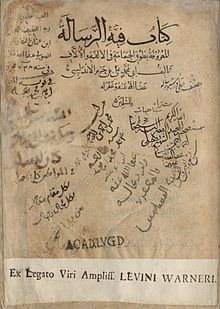

The collar of the dove, manuscript in the Leiden University Library

(Not unproblematic) reconstruction of the Moorish fortress wall (around 1065), plus the moat with corner bastion (from 1593) and the angular "Tower of the Troubadour" in the Aljafería, the city palace of Zaragoza. It represents one of the few buildings of the Taifa period.

Taifa kingdoms around 1037...

Dinar from the time of Hisham II (around 1006/07)

The Caliphate of Córdoba around 1000

Ruin of the main mosque of the Madīnat az-zahrāʾ residence founded in 936.

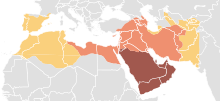

Islamic dominion around 910

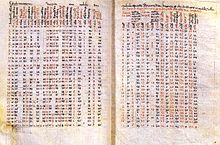

Beati in Apocalipsin libri duodecim (Beato de Zamora), f. 107r. The Visigothic manuscript consists of 144 ff of parchment of two columns of 33 to 35 lines each; Mozarabic miniatures, Biblioteca de Serafín Estébanez Calderón y de San Millán de la Cogolla, 1st half 10th century.

Mosque of Córdoba, begun in 784 and extended several times until 987

Islamic expansion: Conquests under the founder of the religion Mohammed, 622-632 among the four "rightly guided caliphs," 632-661 under the Umayyads, 661-750

Asturias-León, Castile

Independence struggle against Córdoba, Kingdom of Asturias-León

The Visigoth Pelagius was supposedly elected king (or prince) by his followers in 718. He scored a defensive victory at the Battle of Covadonga, which in retrospect has been interpreted as the beginning of the Reconquista. However, it was a private dispute with the Muslim governor in charge of Asturias that gave rise to the rebellion. More tangible is King Alfonso I († 757), who created a belt of devastation between his kingdom and the Muslim territory through murders. Under his son Fruela I began the Repoblación, the repopulation of depopulated areas by Christians. Galicia was also subjugated.

Alfonso II. (791-842) resumed the conquests. The capital was now Oviedo, founded in 761. Under Alfonso III. (866-910), Asturias achieved its greatest expansion and temporary suzerainty over the Muslim south. His three sons divided the kingdom among themselves and the partial kingdoms of León, Galicia and Asturias were formed. In 924 they were reunited as the Kingdom of León.

The first king of León was García I. He married a daughter of the Castilian Count Nuño Fernández, who in 910 had supported García and his two brothers Fruela and Ordoño in a rebellion against their common father. García received León, his brothers Ordoño Galicia and Fruela Asturias. The childless García was succeeded by his brother Ordoño II, who had been sent to Saragossa to be educated by the Banu Qasi. He had the cities of Évora and Mérida sacked. Córdoba was defeated in the battle of San Esteban de Gormaz in 917, but the Christians were defeated in the battle of Valdejunquera in 920. A counterattack led to the occupation of La Rioja and the conquest of the territories around Nájera and Viguera in Navarre. Ordoño II, who had summoned the Counts of Castile but they did not show up, summoned them to Tejares and had them summarily murdered.