History of Russia

The history of Russia provides an overview of the prehistory, formation and development of the Russian state.

Starting from the earliest settlement of the present Russian territory since the Paleolithic Age, this article deals with the emergence of the Empire of Kiev (from 980 to 1240), Kievan Rus, the first major East Slavic empire, which formed in the 10th century, entered the Christian ecumenism by accepting Christianity from Byzantium (988/89), and finally fell victim to the Mongol storm. From the conglomeration of East Slavic constituent principalities left by the collapse of the Empire of Kiev came the period of successor empires (in the west from the mid-13th to the mid-14th century, in the east until the second half of the 15th century). which fell under the rule of the Golden Horde. During this period, Russia became increasingly alienated from the rest of the Western cultural sphere.

With the increasing disintegration of the Golden Horde and the simultaneous internal and external consolidation of northeastern Rus around the Grand Duchy of Moscow, a territorial expansion began - favoured by the spatial structure - that has decisively shaped Russian history ever since. A phase of internal disruption, the so-called Smuta, at the beginning of the 17th century was followed by several wars against Poland-Lithuania and wars against the Ottoman Empire. Tsar Peter I modernized the Russian Empire, which had been imperial since 1721, with the reforms named after him and brought it closer to Western Europe. In the course of the 18th century, the Russian Empire consolidated its great power status, acquired at the beginning of the century, and further expanded it. However, the rapid spatial expansion at this time left little state resources for internal development, as the real social product soon stagnated. After the defeat of the Grande Armée under Napoleon in the Russian campaign of 1812, the Russian Empire consolidated its dominance on the European mainland until the middle of the 19th century. However, due to social structures such as autocracy and serfdom introduced at the beginning of the 17th century, the agrarian empire was less and less able to keep pace with the rapidly developing industrialized states until finally Tsar Alexander II initiated a phase of internal reforms after the defeat in the Crimean War.

The reforms accelerated Russia's economic development, but the country was repeatedly destabilized by internal unrest because the political changes were not far-reaching enough and large segments of the population were left out. The February and October Revolutions in 1917 during World War I ended tsarist rule over Russia and subsequently established the socialist Soviet Union, which lasted until 1991. After its dissolution, the Russian Federation went through a difficult transformation process, which initially caused major drops in both national GDP and the economic situation of many people. This was followed by an upswing from 2000 onwards, boosted by the global economy.

"A Thousand Years of Russia" (1862). Monument in front of St. Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod .

Early History

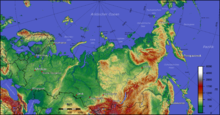

Seemingly endless expanses and the uniformity of vast plains characterize the area. In the south and southwest, mountains (Caucasus and Carpathians) border the Eastern European tableland. The coasts in the north (White Sea) and in the south are weakly indented. To the south, the European lowlands reach only inland seas (Black Sea and Caspian Sea). To the west and east the Eastern European lowlands are open. Neither the western marshes (Pripyet swamps) nor the Ural Mountains are real obstacles to traffic. Western Siberia represents a continental continuation of European Russia. A border runs along the edge of mountainous Central and Eastern Siberia. As there are no west-eastern mountains dividing the East European lowland area, the polar air sometimes reaches deep into the south without being stopped. In terms of natural space, climatic conditions limit human settlement. Almost half of the land is permanently frozen or thaws only on a few days a year. Due to the open borders offering little protection, people in these areas were often threatened by external incursions (cf. also Russian Great Landscapes).

In the vast territory of Russia, people have been recorded for about 100,000 years. Settlement became denser from 35,000 BC in the extensive river basins and climatically favoured zones. The hunter-gatherers lived in hut and tent-like dwellings and caves. With their stone weapons they hunted mainly the mammoth.

The transition to a farming culture took place in some areas since the 6th millennium B.C. Very early, increasingly since the 3rd millennium B.C., horses were tamed and bred. The people of the Kurgan culture, who spread from the lower Volga and the Dnieper basin, used the animal for riding and for pulling wagons. Many nomadic tribes now roamed the vast steppes of Russia with their horses.

Since the 12th century B.C., warlike equestrian nomads, including Scythians and Sarmatians, repeatedly advanced from the Caucasus into the steppes of Russia and in some cases formed early great empires. A precise tribal division cannot be broken down for the period. A first Scythian kingdom emerged in the 7th century BC in what is now Azerbaijan, a second in the 6th century BC on the northern edge of the Black Sea and in the forest steppe. In the 7th century BC, the Greeks also advanced into the Black Sea as part of their colonization movement, founding cities on the southern coast of the Crimea and on the Bug and Dnieper rivers. These Greek cities were of great importance to their northern neighbors. They remained important political and economic bases of the Byzantine Empire after the storm of the migration of peoples, through which a lively trade traffic to the northern neighbours was conducted (cf. Chersones). In terms of linguistic history, the dominance of Slavonic cannot yet be determined. After 500 B.C., apparently more solid communities emerged. More to the north of them, the forest zone was inhabited by Finno-Ugric peoples who pushed westwards, and by Balts.

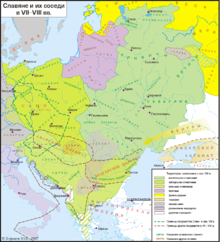

Slavs were originally grasped on the middle Dnieper, north of Kiev. The origin of the name is not clear to this day. At least in part they were dependent on the Gothic Empire. After the destruction of the Gothic Empire, a migration to the north and north-east began. The Slavic tribes that settled directly on the territory of today's Russia were Ilmen Slavs, Krivits, Vyatits and Severyans. They broke through the settlement belt of the Baltic and Finno-Ugric tribes and colonized the forest areas around Lake Ilmen. In the face of the Slavic tribes advancing westward, a common East Slavic language began to emerge by the end of the 10th century. A part of the Slavs came under the suzerainty of the Khazar Empire, which was established between the lower Volga and Don rivers at the end of the 5th century. It included very different ethnic elements (among others Magyars or Alans). The Khazars, of Turkic origin, formed only a minority, but constituted the ruling elite.

Between 552 and 745 the Old Great Bulgarian Empire was located on a part of the present territory of Russia. Around 654, Great Bulgaria was divided into three parts. From the 10th to the 14th century the land between the Volga and Kama rivers belonged to the Volga Bulgarian Empire.

The East Slavic tribes of the 9th century were in different stages of development. The Poljans on the Dnepr around Kiev as well as the Drewljans had united into more solid associations under princes. For the other tribes such indications are lacking. The various tribes took their names from the landscape and were closely related to each other. An exact delimitation of the settlement areas of the tribes is not possible.

In general, the Eastern Slavs were sedentary arable farmers and cattle breeders. Due to the cool continental climate and the few productive soils (the fertile Black Earth region was located in the more southern steppe area), accompanying periodic crop failures and famines, the traditional habitat of the Russians became the forest. Wood was the most important building and fuel material until the 20th century. Forest trades as well as forest beekeeping or hunting represented important economic branches for a long time. Wax and furs and other forest products formed Russia's most important export goods for many centuries. Forests and swamps hindered traffic, which therefore usually went by way of the rivers. The country, however, was only insularly populated. Therefore, it was only possible to develop the countryside from places that were located on major traffic routes. These places were Kiev on the Dnieper, Veliky Novgorod at the confluence of the Volchov from Lake Ilmen and Old Ladoga at the confluence of the Volchov into Lake Ladoga.

Topography of Russia

Territories of the Eastern Slavs (dark green) in the 7th and 8th century

Kievan period (882-1240)

→ Main article: Kievan Rus

The oldest East Slavic state in history was Kievan Rus. It arose in the first half of the 9th century. In it was formed a unified ancient Russian people, on the basis of which subsequently formed the Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian people. This ancient Russian state existed for over three centuries. After the death of the last Grand Prince of Kiev, it broke up into several independent principalities in 1132. This began a period of feudal fragmentation that would soon contribute to the loss of political independence of the Russian lands. The 1220s saw the first clash with the Mongols, when Mongol generals Jebe and Subutai, retreating into Mongolia, crushed the Russians at the Battle of the Kalka. Further, there were lootings of Russian cities.

Rise and bloom

The first medieval state on the soil of what later became Russia was the Norman-Scandinavian rule over a Slavic population, primarily along a trade route connecting Scandinavia with the Byzantine Empire (the route from the Varangians to the Greeks). Due to the weakness of the Khazar Empire and the consequent decline of the Volga trade, this route became increasingly important in the early Middle Ages from the second half of the 9th century. Here Veliky Novgorod and Kiev were the first centres. The dominion of the East Slavic tribes settling here is called the "Rus". The word "Rus" (Russian Русь) is probably derived from a Varangian tribe that came from Sweden (cf. Finnish: "Ruotsi" for Sweden). The Varangians were Scandinavian male bands with mercantile interests, held together as oath communities. They used the river system of Russia as trade routes. To get enough furs and slaves, the Varangians needed wide areas. Therefore, they expanded to the south and east at the same time. Therefore, the trade system became more extensive. In order to secure their trade routes, they established a system of bases from the Baltic Sea to the Duna and Dnepr rivers. Here they met the organizational structures of the Eastern Slavs, Volga Bulgars and Khazars. Thus they also encountered Kiev and gained a foothold there in 839. Kiev was an important trading center with extensive connections as far as Spain and Baghdad. Products of purchase were honey, wax, furs and slaves. As the Kiev trade routes became more dangerous, the warlike merchants of the Varangians took over the place. They adopted culture, way of life and forms of organization and gradually developed more solid forms of organization. Due to the trade, which was mainly directed towards Constantinople, there were close contacts with Byzantium in the following period, despite initial attempts of conquest on the part of Rus (cf. among others the siege of Constantinople (860)).

Also in the north, around Old Ladoga, the Varangians asserted themselves in 862. According to various chronicles (including the Nestor Chronicle), the Slavs called the Varangians to them to end their tribal feuds. The tribal father of this Varangian rule in the north became Ryurik in Novgorod. In 882, Ryurik's successor Igor (878-893) also conquered Kiev, where a Varangian rule had already been established. Igor made Kiev his residence and subjugated the neighbouring East Slavic tribes. The Scandinavians who had settled in Russia were completely Slavicized by the end of the 10th century. Soon "the Rus" became the name of the inhabitants of this area regardless of their tribal affiliation. Thus, the name was transferred from the immigrant Scandinavian ruling class to the long-established inhabitants. At least eight political entities were involved in the formation and consolidation of the Russian state alongside the long-established Slavic peoples such as the Polyans and the Drevlanes: Serbian, Finnish and Lithuanian tribes, the Varangians and the Kazars, the Bulgarians on the Volga, the Byzantine Greeks as missionaries and Arabs as intermediaries between Europe and Asia in international trade. This development was completed in the second half of the 10th century. Due to the multitude of nationalities, this Kievan Empire can therefore be regarded as the first great state in Eastern Slavic history, and it subsequently achieved great prosperity. Thus, at the turn of the first millennium, the fusion of Scandinavians and Eastern Slavs with Byzantine culture and religion gave rise to the population of Kievan Rus, from which Russians, Ukrainians and White Russians later emerged.

The Kievan rulers Oleg and Svyatoslav I waged several wars against the neighboring Kazar Empire to the south, often with Byzantine support. In the 960s, Svyatoslav, with the help of the Pechenegs, finally succeeded in breaking the power of the Kazar Empire. As a result, Svyatoslav extended the influence of Kievan Rus to the Don River and the eastern coast of the Sea of Azov.

The Russian Orthodox Church influenced all areas of life. However, the church did not gain direct secular power as in Western Europe. The bishops and abbots did not become imperial princes. Nevertheless, especially the high clergy was closely connected with politics.

Under Vladimir the Saint, Christianity was raised to the status of state religion in 988/989 and the Kiev population was converted in mass baptisms. His grandmother, Princess Olga (893-924), was the first ruler of the Rurikid dynasty to be baptized, but she was not yet able to establish the Christian faith in the empire. Vladimir thus did not subordinate himself to the Byzantine Empire, but helped the emperor with troops out of military distress and married the emperor's sister, thus symbolizing equality and admitting him to the "family of kings". In 35 years, by 1015, all of hitherto pagan Russia had been converted. This led to the missionaries giving Vladimir the epithet Tsar after his death. The acceptance of Byzantine Christianity at the same time closed Russia a cultural relationship to Roman Christianity. For Byzantium at this time pursued its ecclesiastical policy in deliberate opposition to Rome and imparted anti-Roman tendencies to the Eastern Slavs during their conversion. The Church of Kiev, as a particular church of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, was initially administered by exarchs, which had no effect on the political independence of the Kievan grand princes. In the future, the Orthodox Church and its values formed a supporting social pillar of the Russian Empire.

The Russian nobility (the boyars) was the political ruling class of the empire. Unlike in Western Europe, the prince did not reward his followers with an estate that they could dispose of for life. No feudal system developed out of the allegiance; the relationship remained individualized. Although boyars often took action against princes and tried to limit their power, they did not form a counter-power in the form of a nobility.

In this period there was no difference in principle between Russia and Western Europe. The Russo-Varagian state developed politically and economically within the Romance-Germanic conglomeration of peoples in Europe. The Grand Princes of Kiev were in close contact with their motherland Sweden and the Scandinavian north at least until the middle of the 11th century. Russia's friendly relations with Western European states developed especially in the early 11th century under the reign of Yaroslav I (1019-1054), whose 40-year reign produced a peaceful diplomatic system based on widespread marital connections with the ruling house. As a result of this policy, the princes of Kiev in the 11th century were related to the ruling houses of Norway, Sweden, France, England, Poland, Hungary, the Byzantine Empire, and the Holy RomanEmpire. Under Yaroslav the Wise, Kievan Rus reached a golden age and the height of its power. He managed to consolidate his rule, open up important transport routes and extend Kiev's tributary rule. He had many churches, monasteries, writing schools and fortifications built throughout the empire on the Byzantine model, reformed East Slavic legislation, recorded it in writing for the first time (Russkaya Pravda) and founded the first East Slavic library in Kiev.

Partial princely particularism

From the middle of the 11th century, many changes occurred in the Kievan Empire, which gradually began the decline of the empire. Kiev managed to retain its position as a major trading center, but the empire increasingly disintegrated into smaller principalities.

Like the Holy Roman Empire, the Kievan Empire was not a unified state, but consisted of a large number of autonomous constituent principalities ruled by the Rurikids. One of them inherited the grand dukedom in each case and moved to Kiev to govern. The Kievan Empire did not know a stable and undisputed order of succession to the throne. The empire was divided into individual sovereign principalities, to which a grand prince was superior. There was no written order of succession to the throne as a stabilizing element for the critical moment of the ruler's death. Rather, the seniority principle was followed. There was always one rule: the ruler had to come from the Rurikid dynasty. Crucial to the idea of the Russian order of succession was the equality of the individual princes. The princes referred to each other as "brothers." Eventually, they graded their relationship to each other by adding "elder" or "younger" to primarily reflect rank relationship. Thus, an "elder brother" could be younger than his "younger brother" and be higher in the line of succession. The seniorate was the first permanent system of succession to the throne. Here, it was not the eldest son who inherited the throne, as in primogeniture, but the next brother who had previously ruled another constituent principality. In the event of the death of a prince, a succession procedure developed among the brothers, which led to a change of residence of brothers and sons until 1169. That is, the younger brother of the Grand Prince of Kiev took over his throne, then the next brother, and if he was not present, the eldest son. Thus, the grand dukedom was by no means hereditary in one house, but was awarded according to age precedence in the dynasty.

![]()

Unlike in Western Europe, Russian cities did not form burgher communities that were legally distinct from the countryside. Peasants were also able to participate in city life. No sharp division of labour crystallised between town and country. Until the end of the 18th century, the boundaries between town and country remained fluid, and there were hardly any legal differences.

When in the 11th century the horsemen tribe of the Polovts threatened Kiev and devastated the surrounding countryside, the Slavic population moved from the south of Kiev to the forest zone in the north or westwards to the plains of Galicia and the hill country at the foot of the Carpathian Mountains. This gave rise to settlements that rose to become new centers: the rich merchant city of Novgorod to the north and east, Galicia's capital Halytsch in the far southwest, and the cities of Vladimir, Rostov, and Suzdal. Novgorod itself became an influential merchant republic with a Hanseatic trading post. Only for a short time could Vladimir Monomakh (reigned 1113-1125) restore the unity of the empire. Mostly through military pressure and the installation of his sons as territorial princes, he tied the constituent principalities more closely to the center of Kiev. He advocated a speedy end to the bloody feuds between the princes and joint action against the Polovtsians. Vladimir sought to enforce this view at several princely congresses (1097, 1100, 1103). After the meeting of Dolobsk in 1103, Vladimir Monomakh and the Russian princes allied with him succeeded in inflicting severe defeats on the Polovts in the wake of several military campaigns (1103, 1107, 1111) and in averting the danger emanating from the warlike nomadic people from the Russian land.

However, the increasing political and economic independence of the cities and the discord between the feudal rulers caused increasing alienation, which quickly led to the disintegration of Kievan Rus after his death from 1132 onwards due to ongoing succession struggles over the title of Grand Duke. Thus Kiev was conquered in 1169 by Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky of Vladimir-Suzdal. Instead of settling there, he took the grand ducal title, which had been tied to Kiev until then, north to his new residence near Vladimir. Thus the disintegration of the Kievan Empire continued. The largest states that had seceded from Kiev after its fall were, in addition to the Principality of Kiev, the Principality of Chernigov, the Principality of Pereyaslavl, the Principality of Smolensk, the Principality of Polozk, the Principality of Turov-Pinsk, the Principality of Vladimir-Suzdal, the Principality of Ryazan and Galicia-Volhynia, and Novgorod Land. According to the Nestor Chronicle, in the 12th century there were more than 100 cities in the Kievan Empire, as well as a total population of four to nine million people.

Mongol storm from the east

The disunity of the princes facilitated the Mongol invasion of Rus. A first clash between Rus and the Mongols occurred in 1223, and already in this conflict the disunity of the princes led Rus to disaster. The Mongol generals J̌ebe Noyan and Sube'etai Ba'atur advanced into Rus territory via Georgia and the Kipchak steppe. Previously they had crossed the Caucasus and defeated an army of Kipchaks and Alans on its northern side. The surviving Kipchaks under Kötan Khan fled to the territory of Rus, where they asked for military help against the invaders. The princes Mstislav of Kiev (r. 1214-1223), Mstislav II of Chernigov (r. 1220-1223), and Mstislav Mstislavich of Halitch (r. 1221-1227) formed an alliance with Kötan Khan and mobilized their troops. J̌ebe and Sube'etai had followed the Kipchaks, and in May 1223 the famous Battle of the Kalka took place in what is now Ukraine. As Mstislav, Mstislav II, and Mstislav Mstislavich, owing to their rivalries, led their armies separately and did not coordinate the movements of troops, the Mongols, who were greatly outnumbered, succeeded without difficulty in winning the battle. The Rus troops were almost completely routed, Mstislav and Mstislav II met their deaths, and only Mstislav Mstislavich and Köthan Khan managed to escape. The Mongols did not pursue the fugitives. J̌ebe Noyan had probably been killed in the run-up to the battle of Kipchaken, and Sube'etai Ba'atur moved east and returned to Mongolia. Genghis Khan's orders were not for conquest but merely for reconnaissance of the territories west of the Caspian Sea, and so the Mongols disappeared as abruptly as they had appeared.

The princes were also unaware that after Genghis Khan's death in 1227, the Mongols had elected his son Ögädäi as Great Khan, and at his imperial assembly held in 1235 in Qara Qorom, the ruler's seat, it was decided, among other things, to attack the West. A grandson of Genghis Khan, Bātŭ, was designated as commander. After lengthy preparations, the Mongol advance began. The first to fall victim to them were the Volga Bulgars, whose empire around Kazan on the middle Volga River possessed a significant role as a trading hub. In the winter of 1237/38 the Mongols invaded the principalities of Ryazan, Vladimir and Suzdal. Here the Grand Prince Yuri II and all his sons perished. Bātŭ advanced as far as Toržak in the borderlands of Novgorod, but turned back when thaws turned the roads into swamps. This spared Novgorod and the northwestern principalities. Bātŭ established a residence at Sarai on the lower Volga and from there made advances against the southeastern principalities. In 1239 Černigov and Perejaslavl fell, and on December 6, 1240, the old imperial capital of Kiev. In rapid advance the Mongols roamed the southwestern principalities of Rus, invaded Poland, took Cracow, devastated Wroclaw, and from there moved on to Hungary. While the Mongol advance remained an episode for the lands of Poland, Bohemia, and Hungary, it meant permanent subjugation to Mongol rule for the principalities of Kievan Rus. At the same time, the Mongol storm and the constant threat to the Eastern Slav peasant settlements near the steppes triggered a gradual shift of settlement, i.e. a relocation of peasant settlements from the forest-steppe zones in the south and a migration movement to the northern taiga.

Partial principalities of Rus in 1237 at the beginning of the Mongol storm

The extent of Kievan Rus about 1000: The Russian land stretched from the left tributaries of the Vistula to the foothills of the Caucasus, from Taman and the lower course of the Danube to the coast of the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga.

Questions and Answers

Q: Who were the first people to settle in Russia?

A: The East Slavs, Turkic, and Finno-Ugric peoples were the first to settle in Russia.

Q: What happened during the 13th century?

A: During the 13th century, Mongols conquered the region and created the Golden Horde.

Q: How did Poland-Lithuania invade Moscow?

A: Poland-Lithuania invaded Moscow by force.

Q: When did Napoleon try to invade Russia?

A: Napoleon tried to invade Russia during the winter of 1812.

Q: What happened in 1917 that changed Russian history?

A: In 1917, The October Revolution happened and led by Lenin, communists created a new government called the Soviet Union.

Q: Who failed to invade Russia during WW2?

A: Hitler failed to invade Russia during WW2.

Q: What event caused modern day Russia to form in 1990s?

A:The end of the Union due to events such as Yugoslavia revolution caused modern day Russia to form in 1990s.

Search within the encyclopedia