History of Europe

![]()

This article or subsequent section is not sufficiently supported by evidence (for example, itemizations). Information without sufficient evidence may be removed soon. Please help Wikipedia by researching the information and adding good supporting evidence.

The history of Europe is the history of the people of the European continent, from its first settlement to the present day.

Classical antiquity began in ancient Greece, which is generally considered the beginning of Western civilization and exerted an immense influence on language, politics, educational systems, philosophy, natural sciences and the arts. Greek culture, which had spread over much of the eastern Mediterranean world during Hellenism, was taken over by the Roman Empire, which, after conquering Italy beginning in the 3rd century B.C., gradually spread from Italy throughout the Mediterranean region, reaching its greatest extent in the early 2nd century A.D. The Roman Empire, which was the first to be conquered by the Roman Empire, was the first to be conquered by the Roman Empire. The Roman emperor Constantine the Great promoted the rise of Christianity as the state religion in the empire with the Constantinian turn and moved his residence to the east of the empire to Constantinople, today's Istanbul.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, large parts of southeastern Europe remained in the sphere of power of the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium), while the area of the former Western Roman Empire went through an unstable period in the course of the migration of peoples and several Germanic-Roman empires were formed here. Charlemagne, crowned Emperor (in the West) by the Pope in 800, ruled large parts of Western Europe, which, however, was soon attacked by Vikings, Muslims (Islamic expansion already since the 7th century) and Magyars (Hungarian invasions). The Paderborn Epic, a work of the Carolingian Renaissance that swept the Occident, declared him the "Father of Europe" (pater Europæ). As the early Middle Ages progressed, a number of new empires arose in Europe and a reshaping of the Roman heritage took place. The European Middle Ages were characterized, among other things, by the emergence of the feudal system, an order of estates and a strong role of the Christian religion in culture and everyday life. The Mongol invasion in the mid-13th century and the plague epidemic in the mid-14th century dealt severe blows to the European feudal system.

The Renaissance, the renewed cultural revival of Greco-Roman antiquity, began in Florence in the 14th century. The spread of printing, starting with the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in Mainz, promoted the movements of humanism and the Reformation. The age of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation was marked by numerous religious wars, culminating in the Thirty Years' War and the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. The Christian Reconquista of Spain and Portugal led to the Age of Discovery in North and South America, Africa and Asia, the establishment of European colonial empires, and the "Columbian Exchange," the exchange of plants and animals between the Eastern and Western Hemispheres.

The Industrial Revolution, starting in Great Britain, promoted the mechanization of work processes and international trade. The Enlightenment called for the separation of powers. It was the harbinger of the French Revolution of 1789, from which emerged as the new ruler of France Napoleon, who fought several wars until 1815.

The first half of the 19th century was marked by further revolutions, from which the bourgeoisie and the working class in France and England emerged stronger. In 1861, the Kingdom of Italy and in 1871 the German Empire emerged as nation states, like most of the states in Europe at the time, in the form of constitutional monarchies. Towards the end of the 19th century, the competition between the great European powers intensified in the course of imperialism, until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. The Russian October Revolution of 1917 led to the formation of the communist Soviet Union. Dissatisfaction with the results of the First World War, as well as the world economic crisis of 1929, favored the rise of National Socialism in Germany, Fascism in Italy, Francoism in Spain, and ultimately led to the Second World War.

After the end of the war in 1945, Europe was divided by the "Iron Curtain" between the U.S.-dominated West and the Soviet-dominated Eastern Bloc during the Cold War period. In 1989, the Iron Curtain fell and the power of the Communists eroded in all Eastern Bloc countries. This caused a change in the system of government in the GDR, Poland, Hungary, the ČSSR, as well as Bulgaria and Romania. By 1991, most Soviet constituent states became independent and the Soviet Union itself dissolved. From 1991, the disintegration of Yugoslavia occurred. With the dissolution of the Eastern bloc, the geopolitical situation in Europe changed fundamentally, which opened up opportunities for deepening integration within the framework of European unification, but also for preparing for expansion in the East. With the EU enlargement, most of the states and territories of the former Eastern Bloc joined the EU by 2007.

The influence of history on the cultures of Europe can be mapped geographically in six distinct "historical cultural regions."

Political breakdown (2006)

Satellite view

Topography

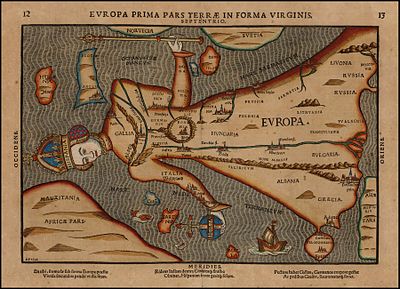

Europa Regina in Heinrich Bünting's Itinerarium Sacrae Scripturae (1582)

Origin of the term "Europe

Name

There are three theses on etymology, none of which can be definitively verified. One explanation for the word Europa refers to the Phoenician word ereb for "dark, evening, setting". From the point of view of the Phoenicians, who settled on the eastern Mediterranean coast, it would therefore mean "land of the setting sun" or "evening land".

Another thesis refers to Greek: the word Εὐρώπη Eurṓpē is understood as a compound from ancient Greek εὐρύς eurýs "wide" and ὄψ óps "view", "face" - hence Eurṓpē "the [woman] with the wide view".

A third explanation refers to various female deities who bore the name Europa as an epithet, which was transferred to the continent.

Myth

→ Main article: Europa (mythology)

There are various legends of the abduction of Europa in Greek mythology. Ovid tells in the "Metamorphoses" that Europa, the daughter of the Phoenician king Agenor, was walking with her companions on the beach of the Mediterranean Sea. Zeus fell in love with the beautiful girl and decided to kidnap her. He took the form of a white bull that rose from the sea and approached Europa. The girl stroked the extremely beautiful, trusting animal and finally found herself willing to climb on its back. Thereupon the bull rose and rushed into the sea, which he crossed with Europa on his back. Zeus carried Europa off to Crete, where he revealed himself to her in his divine form. He begat with her three sons: Minos, Rhadamanthys and Sarpedon. Due to a promise of Aphrodite, the continent to which Crete belongs was named after her.

Titian: Rape of Europa, 1559-1562, panel painting, 185 × 205 cm, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston

Prehistory and early history

Prehistory

Oldest proofs of representatives of the genus Homo come at present from the Sierra de Atapuerca in Spain and are up to 1.2 million years old. Even older fossil findings from Georgia (outside the currently valid borders of Europe) are 1.8 million years old and are called "Homo georgicus". In northern alpine Europe the oldest occupation horizon begins with Homo heidelbergensis about 600,000 years ago. However, the assignment of the finds to an independent species is controversial; many paleoanthropologists uniformly refer to the members of the first wave of emigration from Africa (out-of-Africa theory) as Homo erectus, which had already colonized Java about 1.8 million years ago.

While the development of Homo sapiens started in Africa about 160,000 years ago from the remaining populations of Homo erectus, Europe became the domain of Homo heidelbergensis, which had already developed from Homo erectus, and of Neanderthal man, which had emerged from it. It was not until about 35,000 years ago that Homo sapiens arrived in Europe in a second wave of emigration of the genus Homo (cf. Human dispersal) and gradually replaced Neanderthal man (cf. Cro-Magnon man). With the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, a long history of great cultural and economic achievements began in Europe, first in the Mediterranean region, then also in the north and east.

For northern Europe, several ice ages were decisive for the further development of the geological formations in particular. These glaciations affected present-day Scandinavia, Iceland, Ireland, northern Germany, Poland and Russia. The last main glaciation period lasted from about 23,000 to 10,000 BC.

Essentially, a distinction is made between

- Soft Lake Ice Age (about 70,000 years ago),

- Saale ice age (about 280,000 years ago),

- Elster Ice Age (about 500,000 years ago).

Middle Stone Age

The period after the end of the last glaciation in Europe is called the Middle Stone Age. Dense forests spread across Europe and the few people who lived nomadically in small clans of about 20 people as hunter-gatherers had to get used to the new environmental conditions.

Neolithic period, Neolithic

→ Main article: Settlement history of Europe in the Neolithic period.

In a long development, beginning in the 10th millennium BC, agriculture began to develop in the Fertile Crescent. This development, also known as the "Neolithic Revolution," spread to Europe in the 6th millennium BC.

To the west, this spread along the coasts of the Mediterranean, to the northwest along the Danube into western Central Europe. To the northeast around or along the coasts of the Black Sea. The routes of dispersal to the east have been little explored so far.

Evidence of permanent human settlements (Homo sapiens) dates back to 5000 BC. From this time, for example, settlement remains of the Bandkeramiker were found at the Lahn in Wetzlar-Dalheim. The half-timbered houses each have a 30 meter long ground plan. They are protected by a ditch about two meters deep as well as a rampart in front. To ensure the water supply, two independent wells existed within the fortification.

Bronze Age

By around 1800 BC, the working of bronze had become established throughout Europe (beginning of the Bronze Age).

Iron Age

Around 800 BC, people in Central Europe began smelting iron. The carriers were the cultures of the Hallstatt and Latène periods attributed to the Illyrians and Celts.

See also: Three-period system and prehistory

Advanced civilizations

The first advanced civilization in Europe was that of the Minoans on the island of Crete, which began around 2000 BC. Strongly influenced by this, the Mycenaean culture developed on the nearby Greek mainland from about 1700 BC.

![]()

The following paragraph needs a revision: Almost nothing fits: The expansion of the Celts (to the southeast and to the Iberian Peninsula) began only centuries after the end of the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures.

Please help to improve it and remove this mark afterwards.

From the 6th century BC, the Celts spread across Central Europe to Spain and what is now Turkey. Since they left no written records, knowledge about them is fragmentary. The Romans encountered them and wrote down quite a bit about them. These records and archaeological excavations form the core of our information about this very influential culture. The Celts (Gauls) represented a serious, though not very organized, opponent for the Romans. In the last three centuries B.C., the Romans conquered, among other places, all of southern and southeastern Europe and large parts of central and western Europe

Migration and the end of antiquity

→ Main article: Migration of peoples

At the end of the 4th century, with the advance of the Huns into Eastern Europe, the so-called migration of peoples began, which triggered a wave-like flight movement of several (mainly Germanic) tribal groups, and which ended with the invasion of the Lombards in Italy in 568. Today, many aspects of the migration of peoples are considered in a more differentiated way. In this context, it is emphasized that the invading Germanic groups were less interested in destruction than in sharing in the ancient culture, which was still cultivated in the Germanic-Romanic successor realms in the 6th century. In 476, the Western Roman Empire "fell," but it was hardly perceived as such by contemporaries (because an emperor still ruled in Constantinople) and only acquired greater significance in retrospect.

After the end of antiquity, the historical landscape in Western Europe was determined by more or less long-lived new formations of various empires. The Hellenistic Eastern Roman Empire, also called the Byzantine Empire in modern times after its capital Byzantium, on the other hand, was able to hold on for another millennium until the conquest of its capital in 1453.

The Arab expansion, which began in the 1930s, brought Islamic culture to the Mediterranean coasts, from Asia Minor to Sicily and Spain. The rapid Arab conquests were also a consequence of the weakening of Eastern Rome, which had been at war with the Sassanid Empire until 628. Eastern Rome was able to hold a remnant empire and thus bring the Arab advance to a halt in the east. The Arab invasion of the Mediterranean world marked the definitive end of antiquity, although the epochal boundary between late antiquity and the early Middle Ages is fluid.

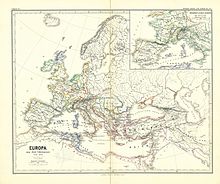

Europe in the years from 476 to 493 (map from 1874)

Middle Ages

→ Main article: Middle Ages

In the era of transition from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages, the Merovingian period, urban culture withered, trade declined sharply, and people returned to rural communities. Feudalism replaced the Roman central administration. The only institution to survive the collapse of the Western Empire was the Church, which preserved some of the Roman cultural heritage and was a focus of education and scholarship outside Byzantium until the 14th century. Byzantium was at the height of power under Emperor Basileios II, but subsequently lost several territories and influence.

After Charlemagne's coronation by Pope Leo III as Roman emperor in 800 (thus renewing the ancient Roman Empire in the minds of contemporaries), the emperor's new main residence, Aachen, became a center of the arts and sciences, giving rise to the Carolingian Renaissance, the revival of culture with a return to antiquity. Charles conquered large parts of Italy and other surrounding countries, thus enlarging his empire (see map). He received help from the Pope, who could no longer rely on the protection of the Byzantine Empire. In this way, the Pope first became a vassal of the Emperor, protecting Rome from the danger of Lombards and Saracens, but later the Pope's estates became an independent Papal State in central Italy.

The division of the empire among its descendants led to the emergence of the West Frankish Empire, from which France emerged in the 9th and 10th centuries, and the East Frankish Empire, which became the Holy Roman Empire (though so called only since 1254) with the coronation of Otto I as emperor in 962. During and after the wars of succession, the feudalistic system gained in importance. The Roman-German Empire never developed into a nation-state and represented an explicit universal claim (see Imperial Idea). However, the position of the kingship vis-à-vis the strong sovereigns was comparatively very weak, so that a consensual form of rule developed.

The Norman conquest of England and southern Italy were milestones in European history. In England, the House of Plantagenet established itself in the 12th century, which also had considerable possessions in the Kingdom of France. This led to repeated conflicts, including military ones, with the French crown, which consolidated its power more strongly from the late 12th century onward. The culmination of this development was marked by the Hundred Years' War in the 14th and 15th centuries. A Norman kingdom emerged in southern Italy and Sicily, which fell to the Hohenstaufen dynasty in the late 12th century before passing to the House of Anjou in the 1260s.

In the 11th century, the independent city-states of Italy, such as Venice and Florence, flourished economically and culturally, and at the same time the first universities in Europe were founded in Italy. In addition to the Holy Roman Empire, France and the Papal States, kingdoms such as England, Spain (see Reconquista), the Kingdom of Hungary, the Kingdom of Poland and Kievan Rus were formed. In contrast, Germany and Italy still remained fragmented into a multitude of small feudal states and independent cities that were only formally subordinate to the emperor.

In the Oriental Schism of 1054, the church split into the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches. This led to a lasting estrangement between the regions where these denominations were predominant. A low point in the development was the conquest and sack of Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade in 1204. In the late 11th century, the Crusades began in the Near East, which continued with varying intensity into the 13th century.

In the Middle Ages, the most enduring dominions of non-European powers also existed over parts of Europe. Towards the end of the 6th century, the Avars controlled large parts of the Balkans, but their power was already in decline by the 7th century. In the 790s, the Avars were defeated by the Franks under Charlemagne, and the remnant Avar empire was in a final process of dissolution by the early 9th century. In April 711, the Umayyad invasion of southern Spain began, laying the foundation for Arab rule over the Iberian Peninsula that lasted until 1492. At its greatest extent, the domain included not only present-day Spain, Portugal, but also parts of southern France. Arabic writings in the fields of astronomy, physics, alchemy and mathematics were translated into Latin and Castilian, in particular by the Toledo school of translators. The knowledge thus gained came to Italy, among other places, and had a strong influence on the emergence of scholasticism, for example. In the early 1220s, under the generals of Genghis Khan, Jebe and Subutai, the Mongol invasion of Europe began. In what is now Ukraine, they first defeated a Russian army at the Battle of Kalka. From 1237, Jebe and Batu Khan conquered most of the Russian principalities. They advanced into what is now Germany, the Czech Republic and Austria by 1241, and were victorious at the Battle of Liegnitz (Poland) and the Battle of Muhi (Hungary). These conquests became the Golden Horde, which was still a significant power factor until 1502. Due to the Pax Mongolica, there was also increased travel in both directions and a transfer of technology to Europe.

One of the greatest catastrophes to strike Europe was the Black Plague. There were a number of epidemics, but the most severe of all was the "Black Death" from 1346 to 1352, which probably killed a third of Europe's population. The pandemic first occurred in Asia and reached Europe through trade routes. Persecutions of Jews also took place in connection with the plague outbreak.

The end of the Middle Ages is usually associated with the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the final conquest of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottomans. The Ottomans made Constantinople the new capital of the Ottoman Empire, which lasted until 1919 and at its greatest extent encompassed the Near East, North Africa, Crimea, the Caucasus and the Balkans.

The province of al-Andalus in 720

Europe, 814

Conquests of Charlemagne

Renaissance and Reformation

→ Main article: Renaissance and Reformation

By the 15th century, at the end of the Middle Ages, powerful nation-states such as France, England and Poland-Lithuania had emerged. The Church, on the other hand, had lost much of its power through corruption, internal dissension, and the spread of culture that led to the advancement of art, philosophy, science, and technology in the Renaissance era.

In the struggle for supremacy in Europe, the new nation-states were constantly in a state of political change and involved in wars. Especially with the outbreak of the Reformation (from 1520 onwards, according to a pan-European perspective), which Martin Luther helped to bring about with his dissemination of the Theses on Indulgences in 1517, political wars and religious wars ravaged the continent. The "age of schism" led to a rift between Catholicism and Protestantism. In England, King Henry VIII broke with Rome and declared himself head of the church. In Germany, the Reformation united the various Protestant princes against the Catholic emperors from the House of Habsburg. In France, after eight Huguenot wars, culminating in the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in 1572, the Edict of Nantes in 1598 temporarily calmed the situation.

Raphael Santi: The School of Athens (1510/11), Vatican Stanzas, Rome

Colonial expansion

→ Main article: Colonization and European expansion

The numerous wars did not stop the new states from exploring and conquering large parts of the world, especially in the newly discovered Americas. In the early 16th century, Spain and Portugal, leaders in exploration, were the first states to establish colonies in South America and trading posts on the coasts of Africa and Asia, but France, England and the Netherlands soon followed suit.

Spain had control of large parts of South America and the Philippines. Britain had all of Australia, New Zealand, India, and large parts of Africa and North America; France had control of Canada and parts of India (both of which it lost to Britain in 1763), parts of Southeast Asia (French Indochina), and large parts of Africa. The Netherlands got Indonesia and some islands in the Caribbean; Portugal owned Brazil and several territories in Africa and Asia. Later, other powers such as Russia, Germany, Belgium, Italy, outside Europe the United States and Japan also acquired some colonies.

The American War of Independence, which led to the Declaration of Independence of the United States in 1776, as well as the declarations of independence of the South American states, set limits to European colonization.

17th and 18th century

During these two centuries, religious and dynastic tensions reached their peak in the Thirty Years' War from 1618 to 1648, the longest period of warfare involving almost the entire continent. This war began with the so-called Defenestration of Prague and ended with the Peace of Westphalia, which gave extensive sovereignty to the territorial lords in the Holy Roman Empire and initiated the development of nation-states. The Thirty Years' War devastated and depopulated entire regions, and it took more than a generation for the population to recover. The medieval feudal order largely dissolved in the 17th century. The counts and princes lost a great deal of wealth with the steady independence of the population, and in the end the emperor was left only with the impotence of the empire, with petty statehood taking root and nation-states being further strengthened or absolutism becoming the dominant form of government.

The changed power structure left a lasting impression on the culture and collective memory of the people, which had emerged from this discontent and the resulting consequences of the war and now very slowly led to the rise of the bourgeoisie. The resulting boom in trade gave rise to mercantilism as an economic form.

A shock was repeated in Europe in 1683 with the second siege of Vienna after 1529 by the Turks. Through the influence of the Pope, a broad coalition was formed to defend against the Turks. The strongest military power in Europe at that time, France under the "Sun King" Louis XIV, did not participate in the coalition, but used the fact that the German emperor was busy defending against the Turks to continue his wars of reunion.

In terms of intellectual history, the Renaissance was continued by the philosophy of the Enlightenment, which weakened the position of religion and laid the foundation for the first democracy movements. The natural sciences achieved great progress; with inventions such as the steam engine, the industrial revolution began in the late 18th century, and the economy developed into early capitalism. The philosopher Karl Jaspers attributed Europe's industrial and cultural distinctiveness to the triad of "faith, science and technology." Beginning in 1756, the Seven Years' War was fought by Prussia and Great Britain on one side against Austria, France, and Russia on the other. The main change on the continent was the rise of Prussia as a great power; the world political result was that France lost a large part of its colonies to Great Britain, which thus laid the foundation for its world empire.

Towards the end of the 18th century, the refusal of King Louis XVI of France, supported by the nobility and the Church, to give more influence to the so-called third estate led to the French Revolution of 1789, an authoritative attempt to create a new state based on the principles of liberty, equality, fraternity (Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité). The king was executed, a republic was proclaimed in France, and a kind of democratic government was established. In the ensuing turmoil, caused in part by declarations of war by most European monarchies, General Napoleon Bonaparte took power after the coup d'état of 18 Brumaire VIII. The separation of the executive and legislative branches, that is, the separation of powers between legislation and control, was now accomplished in France and marked the beginning of the end of feudalism throughout Europe. In order to prevent the French Revolution from spreading as well as changes in the power structure in Europe, the Coalition Wars began at the end of the 18th century.

The storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789

Versailles in 1715

19th century

In the numerous wars of the Napoleonic era, Napoleon defeated the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor several times, who assumed the title of "Emperor of Austria" in 1804 and laid down the Roman-German imperial crown after the formation of the so-called Confederation of the Rhine in 1806, which meant the end of the Holy Roman Empire as a state. Russia was also defeated militarily by Napoleon on several occasions, and Prussia also suffered a severe defeat in 1806/07. Napoleon temporarily re-established a Polish state in the form of the Duchy of Warsaw, which had been destroyed by Prussia, Austria and Russia in the late 18th century. In 1804 he had himself proclaimed French emperor. In 1815 he was finally defeated at Waterloo.

After the defeat of France, the other European powers at the Congress of Vienna of 1814/1815, under the leadership of the Austrian state chancellor Prince von Metternich, and in the period of the Vormärz between 1815 and 1848, attempted to restore the pre-1789 situation with the help of restoration measures. However, they were unable to stop the spread of revolutionary movements in the longer term. The bourgeoisie was strongly influenced by the democratic ideals of the French Revolution. In addition, the Industrial Revolution brought profound economic and social changes during the 19th century. The working class was increasingly influenced by socialist, communist, and anarchist ideas, especially the theories summarized by Karl Marx in the Communist Manifesto of 1848. Further destabilization came from the formation of nationalist movements in Germany, Italy, and Poland, among other countries, that called for national unity and/or liberation from foreign rule. As a result of these developments, there were a large number of overthrows and wars of independence in the period between 1815 and 1871, such as the revolutionary movements of 1830 and 1848/49. Although revolutionaries were often defeated, by 1871 most states had received constitutions and were no longer ruled absolutistically. Germany was proclaimed the German Empire under Emperor Wilhelm I in 1871 at the Palace of Versailles after the three wars of unification (1864 German-Danish War, 1866 German War against Austria, and 1870/1871 German-French War). Its policy was largely determined by Imperial Chancellor Otto von Bismarck until 1890, see also Otto von Bismarck's Alliance Policy.

Similar to Germany, after the failure of democratic and liberal-minded revolutions and independence movements in the Italian principalities, Italian unification was enforced. After three wars of independence against Austria, the Italian nation-state emerged as the Kingdom of Italy under Sardinian leadership. In 1861, the Sardinian King Victor Emmanuel II was proclaimed Italian king. His prime minister, Camillo Benso Count of Cavour, played a role for Sardinia-Piedmont and Italy similar to that of Bismarck for Prussia and the German Empire. In France, after the fall of Emperor Napoleon III as a result of the French defeat in the war against Prussia and the other German states, the Third French Republic was proclaimed. In the course of the upheavals in France, the citizens and workers of Paris had risen up against the pro-Prussian policies of the young republic in 1871 and founded the Paris Commune. It is considered the first socialist-communist revolutionary attempt, but was bloodily crushed after only a few weeks. The last decades of the 19th century were defined by increasing economic and power competition between the great powers of Central Europe, especially the German Empire, France and Great Britain. This competition led, among other things, to an increased militarization of the respective societies, an arms race, the "race for Africa" and Asia ("Great Game") and to a peak of imperialism and nationalism. In the long run, these developments led to World War I, especially after the dissolution of the Bismarckian alliance system under Kaiser Wilhelm II, which had provided a certain interstate stability until 1890.

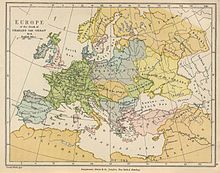

Europe in 1890

Europe after the Congress of Vienna 1815

Early 20th century: World Wars

The 20th century brought dramatic changes to the power structure within Europe and the loss of its cultural and economic dominance over the other continents.

Already during the Belle Époque, the rivalries of the European powers escalated until the First World War was triggered in 1914. The Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria were opposed by the Entente, consisting of France, Great Britain and Russia, reinforced by Italy in 1915 and by the USA and still other states in 1917. Despite Russia's defeat in 1917, the Entente was victorious by the end of 1918. The war was one of the main causes of the October Revolution, which led to the creation of the Soviet Union.

In the Versailles Peace Treaty, the victors imposed harsh conditions on Germany, whereupon a number of new states such as Austria, Hungary, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia were created in the further Paris Suburb Treaties on the territory of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire instead of the multi-ethnic state, with the theoretical aim of promoting the self-determination of peoples. In the following decades, fear of communism and the Great Depression led to the rise to power of authoritarian and totalitarian governments: Fascists in Italy (1922), National Socialists in Germany (1933), Francoists in Spain (after the end of the Civil War in 1939) and also in many other countries such as Hungary.

After Germany and Japan came together in 1936 through the Anti-Comintern Pact, joined by Italy in 1937 and supplemented by military cooperation in the Three-Power Pact in 1940, Nazi Germany, emboldened by the 1938 Munich Agreement and backed by a nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union, triggered World War II with the invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. After initial successes, including the occupation of Poland, France, and the Balkans by 1940, Germany took over by going to war against the Soviet Union and declaring war on the United States in support of Japan. After initial successes, the Wehrmacht was stopped at the Battle of Moscow in December 1941 and suffered a decisive defeat at the Battle of Stalingrad a year later. Allied forces were victorious in North Africa at the First and Second Battles of El Alamein, occupied Italy from 1943, and recaptured France in 1944 with Operation Overlord. In the spring of 1945, Germany was occupied from the east by Soviet forces and from the west by U.S. and British forces. In many places, the Allied soldiers were confronted with a picture of horror. In thousands of concentration and concentration camps inside Germany and in the occupied territories, millions of Jews, Sinti and Roma, Social Democrats, Communists, clergymen, people unable to work, Soviet prisoners of war and Polish civilians had been shot or gassed; many starved to death or died of disease. One week after Hitler's suicide, the Wehrmacht surrendered unconditionally on May 8, 1945. Japan surrendered in August 1945 after the U.S. destroyed the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with atomic bombs.

Europe on the eve of the First World War 1914

From the end of World War II to the end of the Cold War.

The two world wars, especially the second, ended Europe's prominent role in the world. The map of Europe was redrawn when the continent became the main field of tension in the Cold War between the newly emerged superpowers, the capitalist United States and the communist Soviet Union. The "Iron Curtain" formed the dividing line between the Western world and the Soviet-dominated Eastern Bloc, including Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and East Germany. Militarily, the U.S.-led NATO and the Soviet-controlled Warsaw Pact faced each other.

Starting from Western and Central Europe, a process of economic and political integration began within the Western-oriented states: From a coal and steel union, the European Economic Community (1957) developed, which was replaced by the European Union after the Maastricht Treaty in 1992.

In Eastern Europe, a strong desire for freedom developed in the communist satellite states, which, despite some setbacks (1956 in Hungary, 1968 in the CSSR), finally led to the end of the division of Europe after a weakening of the Soviet Union due to economic policy mistakes and an overload from the arms race. The Eastern Bloc disintegrated after the fall of the Iron Curtain beginning in the fall of 1989, followed by the disintegration of the Soviet Union by the end of 1991 and the dissolution of Yugoslavia beginning in 1991. The Iron Curtain, which had divided the European continent into two completely separate blocs during the Cold War, was removed. In the GDR, the Wende and peaceful revolution led to the end of the SED government and resulted in German reunification. As a result of the loss of power of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe, the removal of the Iron Curtain and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, a number of new states were formed in Eastern Europe on the one hand and the European Union was enlarged on the other.

EU Member States and Candidate Countries

Military alliances in the Cold War era

After the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact.

At first, it appeared that the end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the blocs due to general disarmament could lead to a peace dividend and far-reaching democratization. And there was widespread agreement in the majority of European states that economic development should be characterized by deregulation and globalization. The Washington Consensus of 1990 and the transformation of the GATT into the WTO with stronger powers were intended to force a reduction in tariffs. On the other hand, criticism of this policy emerged from Attac (founded in 1998) or, for example, the Nobel Prize winner for economics Joseph E. Stiglitz in The Shadows of Globalization (2002). The breakup of Yugoslavia and, even more so, the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, in the United States by al-Qaida put an end to this hope for peace. Terrorist attacks also occurred in Europe: in Madrid (2004) and in London (2005).

Russia returned to a more nationalistic policy under Gorbachev's successor, Boris Yeltsin. Business leaders enriched themselves disproportionately, while a large part of the population became impoverished. Beginning in 2000, Vladimir Putin used dictatorial methods to reassert state authority, but he allowed serious human rights violations in the internal conflict with Chechnya. In the 2008 Caucasian War, Russia clearly appeared as a hegemonic power.

European integration continued to make progress with the introduction of a common currency, the euro, in what are now 17 countries of the European Union and with the enlargement of the European Union to include Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia, Malta and the Republic of Cyprus on May 1, 2004, and Bulgaria and Romania on January 1, 2007. The Lisbon Treaty of 2009 (signed in 2007, finally ratified December 1, 2009) adapted the structure to the new situation after a constitutional treaty failed in 2005 due to negative votes in referendums in France and the Netherlands.

In 2009, in the course of the global financial crisis, Greece fell into a severe financial crisis due to its high debts, which developed into the euro crisis in 2010, against which a European Stability Mechanism was developed. This prevented a catastrophe with ever new measures, but the fundamental crisis has not yet been ended. Ireland, Spain, Portugal and Italy were also affected by these economic crises. While Ireland was able to stabilize its economy in 2012/2013, the other states, but especially Greece, are still highly indebted.

In March 2014, parallel to a revolution in Ukraine, there was an annexation of the Crimean peninsula, controlled by Russia and supported by Russian military. According to published figures, a hastily improvised vote of the population resulted in a clear majority of more than 90% in favor of annexation to Russia - this in the face of the impossibility of speaking out in favor of the status quo. 100 states of the UN condemned the vote, which could not be a basis for a change of status of Crimea.

Historical cultural regions

In contrast to other continents, for which various models of division into cultural districts (obsolete) or cultural areas were developed at the beginning of the 20th century, Europe was left out for a long time due to its enormously differentiated development and the merging of peoples into nation states. Only since the work of the Hungarian historian Jenő Szűcs, who died in 1988, has a division based on the "historical regions of Europe" been seriously discussed.

The map shows the cultural areas proposed by Christian Giordano in 2002, based on Immanuel Wallerstein's "world system theory," but represents one of many subjective proposals for dividing Europe into historical cultural regions.

cf. cultural areas in Europe according to Hunter and Whitten

| Historical region | Historical similarities | Sample States |

| Periphery | Remote, marginal, and sparsely populated large areas, often subsistence agriculture | Iceland, Ireland, Scotland and large parts of Fennoscandia |

| Northwest Europe | Origin of capitalism, industrial society and modern democracies | England, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, Germany, Switzerland |

| Central Eastern Europe | Supplier of raw materials for northwestern Europe, feudalism and refeudalization, serfdom, latifundia agriculture and aristocratic democracy | Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Hungary and Baltic countries |

| Eastern Europe | Technologically backward agrarian states, serfdom, feudalism and refeudalization, "breeding ground" of communism | Russia, Ukraine and Belarus |

| Mediterranea | Western Roman "cultural successors," aristocracy and latifundia agriculture. | Italy, Portugal and Spain |

| Southeastern Europe | Eastern Roman "cultural successors," Ottoman feudal system, often subsistence farming | Albania, Bulgaria, Greece and the successor states of Yugoslavia |

Historical regions

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the traditional division of European history?

A: European history is traditionally divided into ancient (before the fall of the Western Roman Empire), medieval, and modern (after the fall of Constantinople).

Q: When did Europe's antiquity begin?

A: Europe's antiquity began with the Minoan civilization, Myceneans and later on Homer's Iliad in Ancient Greece around 700 BC.

Q: When was Christianity adopted in Europe?

A: Christianity was adopted in Europe during the fourth century.

Q: What event marked a decline in Western Europe?

A: The fall of the Western Roman Empire marked a decline in Western Europe.

Q: What event sparked an expansion and enlightenment across Europe?

A: The Thirty Years War, Treaty of Westphalia and Glorious Revolution sparked an expansion and enlightenment across Europe.

Q: What event led to revolutions across continental Europe?

A: The French Revolution led to revolutions across continental Europe as people called for liberty, equality, brotherhood.

Q: What event marked the collapse of Communism in Eastern Bloc countries? A: The collapse of Communism in Eastern Bloc countries was marked by Soviet leader Gorbachev making clear that he would not force these countries to stick to Communism which eventually led to the Berlin Wall being torn down in 1989 and the Soviet Union collapsing in 1991.

Search within the encyclopedia