Herpes simplex

![]()

This article explains the diseases colloquially known as herpes; for other diseases, see Herpes.

Herpes simplex (Latin simplex 'simple') refers to various viral infections caused by herpes simplex viruses. Colloquially, the shortened form herpes is usually used for a specific localisation on the skin. The word comes from the ancient Greek ἕρπειν herpein ('to creep'), meaning the creeping spread of the skin lesions in a herpes simplex infection (also in the form of herpes febrilis with cold sores).

Herpes simplex is one of the sexually transmitted diseases.

The causative agents of herpes simplex infections are two different viral species: herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) and herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2). They show minor differences with regard to their clinical pictures and the localization of the disease. According to the occurrence as well as the localization of the disease symptoms, clinically different HSV infections are designated, of which mainly herpes simplex labialis (labial herpes) and herpes simplex genitalis (genital herpes) are common. In addition to these forms, there are also rare, severe HSV infections such as generalized HSV sepsis in patients with immunodeficiency, herpes simplex encephalitis and generalized HSV infection of the newborn (herpes neonatorum).

After a (also symptomless) initial infection, the virus always remains in a dormant state (latency) in the organism for life, which is referred to as a persistent infection. This property of persistence is found in all members of the Herpesviridae family. The therapy of HSV infections is not able to end this persistence, but it tries to prevent the reproduction of the virus after a reactivation from the dormant stage. Several highly specific antivirals are available for HSV therapy.

History

The genital manifestation of herpes simplex was already described by Hippocrates around 400 BC as a symptom of a spreading vesicular disease. The fact that the disease is also transmissible was known at the latest in Roman antiquity, as Emperor Tiberius forbade kissing during public ceremonies because the spread of vesicular disease was observed on the lips. This was documented by Aulus Cornelius Celsus as the first epidemic of a possible herpes disease. In 16th and 17th century Europe, herpes labialis was also widespread and its transmission through kissing was common knowledge. For example, William Shakespeare wrote in his well-known tragedy Romeo and Juliet, "O'er ladies' lips, who straight on kisses dream, Which oft the angry Mab with blisters plagues, because their breaths with sweetmeats are tainted." (Translation: "O'er ladies' lips that straight on kisses dream, Often the angry Mab with blisters plagues these, Because their breaths with sweetmeats are tainted"; erg. Explanation: The name Mab in the quotation refers to the fairy "Queen Mab", who appears in the work in a speech by Mercutio).

In 1736, Jean Astruc recognized genital herpes as a disease in its own right, and not as a variant of gonorrhea or syphilis as previously assumed. In 1883, the German dermatologist Paul Gerson Unna described the frequency of the disease and its co-occurrence with other venereal diseases. He also conducted the first histological studies on herpes simplex. After Wilhelm Gürtler was able to experimentally transfer the causative agent of herpes keratitis (herpes corneae) to a rabbit eye in 1913, Ernst Löwenstein found the identity of the causative agent of both diseases by transferring vesicular contents of herpes labialis to a rabbit eye. HSV was finally isolated and characterized for the first time from vesicle contents of a patient by Slavin and Gavett in 1946. The first electron microscopic imaging of herpes simplex viruses was achieved by Coriell in 1950, and it was not until the 1960s that Andre Nahmias and especially Karl Eduard Schneweis discovered that herpes simplex infections were caused by two different viral species, which researchers were able to distinguish on the basis of their different antigenicity.

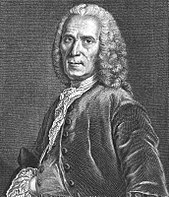

Jean Astruc

Pathogen

Herpes simplex viruses

The two causative agents of herpes simplex infections - herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2 - which are also taxonomically and more correctly referred to as human herpes virus 1 and 2 (HHV-1/2), belong to the simplex virus genus of the family Herpesviridae. Members of this genus related to the herpes simplex viruses are also found in animals, where these viruses cause similar diseases in cattle, for example, or spider monkeys, macaques, and other guenon relatives. Although herpesviruses are generally strictly specialized to their respective hosts, rarely the macaque cercopithecine herpesvirus 1 (herpesvirus simiae), which is similar to HSV-1, can be transmitted to humans, where it can cause severe, generalized infections.

With a diameter of 140 to 180 nm, the herpes simplex viruses belong to the large viruses. A linear, double-stranded DNA is located in an icosahedral capsid as the genome. The capsid in turn is surrounded by a viral envelope, which leads to a sensitivity of the viruses to soaps, detergents or already mild disinfectants. Between the capsid and the viral envelope is a multitude of viral proteins, the so-called tegument proteins, which are responsible, among other things, for the regulation of gene expression in the host cell and the transition of the virus into a dormant latency stage. As a double-stranded DNA virus, the herpes simplex viruses are genetically stable; mutations and the emergence of natural variants are rather rare.

Transmission and dissemination

Herpes simplex viruses are distributed worldwide, and humans are their only natural reservoir. Since HSV-1 is already acquired through saliva contact and smear infection from infancy in normal family contact, it is common in the population. The virus shows an age-dependent seroprevalence, which reaches high percentages around the end of puberty and then increases only slightly further. In Germany, antibodies against HSV-1 could be detected in 84 to 92 % of the persons of an age-normalized random sample examination.

HSV-2 is transmitted through close mucosal contact when the virus is reactivated in the virus carrier and replicates again in epithelial cells. Viral shedding can also occur without visible lesions. The prevalence of antibodies against HSV-2 is distributed differently. It is particularly influenced by age and sexual activity; likewise, geographic distribution varies. In healthy blood donors or health surveillance, there have been frequencies ranging from 3% to 23% in the United States. This figure is significantly higher in patients who consulted a physician for another sexually transmitted disease (up to 55%) or engaged in commercial prostitution (up to 75%).

Infection mechanisms

In a primary infection, the HS viruses penetrate via the mucosal cells of the oral pharynx (predominantly HSV-1) and the genital tract (predominantly HSV-2). Areas at the transition from mucous membrane to normal skin are preferentially infected. Here the viruses multiply in the epithelial cells. The spread of the herpes simplex viruses within the epithelium occurs by destruction of the host cells and release of new virions or by fusion of adjacent cells, whereby the unenveloped virus capsids infect the new cell. Destruction of the epithelial cells manifests clinically in an inflammatory reaction, often forming an ulcer or inflammatory skin vesicle due to tissue destruction. The vesicular fluid is an exudate in which herpes simplex viruses accumulate in a high concentration (>100,000 PFU/µl).

By direct cell-cell contact or by virions in the interstitial fluid, HSV reaches the nerve endings of sensitive neurons, from which it is specifically taken up and transported along the microtubules and intermediate filaments of the axon to the cell body of the nerve. This retrograde axonal transport occurs by binding of the virus (as a naked viral capsid, possibly with residual tegument proteins and coat proteins) to kinesin-like proteins and dynein. The migration speed towards the cell body is about 0.7 µm per second.

Search within the encyclopedia