Hemorrhoid

Haemorrhoids, also called haemorrhoids (ancient Greek αἷμα haima "blood" and ῥεῖν rhein "to flow"; obsolete terms blind veins, golden veins, gold veins), are arteriovenous vascular cushions, which are arranged in a ring under the rectal mucosa and serve the fine closure of the anus. They are varicose dilations of the veins of the rectum in the area of the sphincters of the anus. When hemorrhoids are mentioned, however, this usually refers to enlarged or deeper hemorrhoids in the sense of hemorrhoidal disease, which cause discomfort. These complaints are mainly repeated anal bleeding and anal oozing, excruciating itching and stool smearing.

Symptomatic hemorrhoids are one of the most common conditions in the Western world, but largely tabooed by society. It is a disease of old age. Hemorrhoidal disease before the age of 35 is rare. The causes of the disease are still largely unexplained. Symptomatic hemorrhoids are a progressively progressive disease that is classified into four grades of disease. Due to its high prevalence, the diagnosis of 'haemorrhoidal disease' is often made very lightly and frequently by the sufferers themselves. However, some much more serious diseases are characterized by very similar symptoms.

Hemorrhoidalia, which are mainly ointments and creams for the treatment of hemorrhoidal disease, can at best alleviate the symptoms. It is neither a cure nor a stop of the progression of the disease possible. Basic therapy can at least slow down the progression of the disease. A cure is only possible through surgical interventions. In the early stages of the disease, these interventions can be performed on an outpatient basis and are minimally invasive. Advanced hemorrhoidal disease can only be cured by surgery with inpatient hospitalization. In many cases, those affected only seek medical treatment when the pain and discomfort outweigh the feeling of shame.

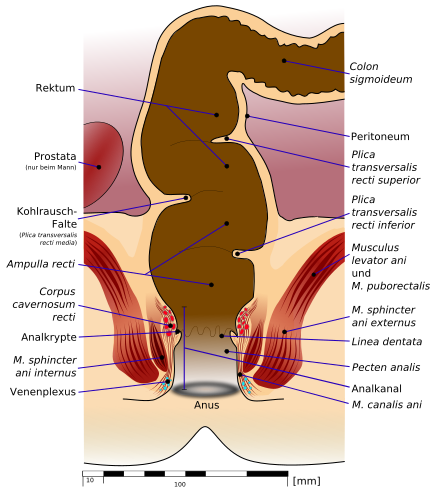

Anatomy and function of the hemorrhoidal plexus

The haemorrhoidal plexus, also called corpus cavernosum recti or plexus haemorrhoidalis superior, is a broad-based, spongy, arteriovenous vascular cushion which lies annularly under the mucosa of the end of the rectum (the submucosa of the distal rectum) and normally ends immediately above the boundary line (linea dentata) between the anal canal and the rectum. This erectile tissue is held in the upper anal canal by the canalis ani muscle and elastic fibres.

The corpus cavernosum recti was formerly also called zona haemorrhoidalis. This name has been deleted from the anatomical nomenclature, since haemorrhoidalis denotes a pathological condition.

Arterial supply

The haemorrhoidal plexus is a component of the continence organ and is supplied arterially by the superior rectal artery. Although the vascular cushion is annular, the anatomical position of the usually three blood-supplying branches of the superior rectal artery causes the cushion, the main hemorrhoidal node, to be emphasized in three sectors, namely in the 3 o'clock (left as seen from the patient), 7 o'clock and 11 o'clock (right as seen from the patient) anatomical positions. According to the definition of the lithotomy position, the 6 o'clock position always points to the tip of the coccyx, regardless of the examination position. Minor nodes can be assigned to the major nodes. Thus, the 7 o'clock major node has two minor nodes at 9 and 6 o'clock, and the 3 o'clock major node has two minor nodes at 1 and 4 o'clock. The 11 o'clock principal node rarely develops accessory nodes; when it does it is at 12 o'clock. Thus, an adult usually has three major hemorrhoidal nodes and four, at most five, minor hemorrhoidal nodes. The hemorrhoidal nodes (hemorrhoids) develop during puberty and are not a pathological finding, but normal. Although the pathological changes of this cavernous body have been known to mankind for thousands of years as hemorrhoidal disease, the hemorrhoidal plexus - the anatomical normal - and its function were not discovered until the middle of the 20th century. The arteria rectalis superior can show individual variations and, for example, form up to five terminal branches, which then feed the hemorrhoidal plexus.

Venous outflow

The venous outflows of the haemorrhoidal plexus pass through the internal and external sphincter muscles (Musculus sphincter ani internus and externus, respectively), which together with the haemorrhoidal plexus and other muscular, nervous and epithelial structures form the continence organ. The hemorrhoidal plexus closes the anal canal from the inside. For this purpose, the hemorrhoidal nodes interlock in a star shape. This causes the fine sealing of the anus, which is very important for anal continence, i.e. the ability to hold back defecation for a certain time or to voluntarily trigger the excretory process. The contribution of the corpus cavernosum recti to continence at rest is about 10 to 15 %. When the internal sphincter is strained, venous outflow is throttled and the hemorrhoidal plexus fills with blood. This prevents the passage of feces and intestinal gases. In this function, the corpus cavernosum recti also plays an important role developmentally in human socialization.

Anal canal closure mechanism

The sphincters of the anus alone would not be able to close the anal canal. Even with a maximum contraction of these ring muscles, an opening of about 10 mm diameter would remain, which can only be closed by the canalis ani muscle and the corpus cavernosum recti sitting on top of it.

If the nerve endings of the rectum signal to the brain that there is enough faeces in the ampulla recti of the rectum, the need to defecate arises. The internal sphincter then relaxes, and blood flows from the hemorrhoidal plexus, opening the obstruction and allowing feces to be expelled. This process is involuntary. The external sphincter, on the other hand, which is supported by the pelvic muscles, can be used to control bowel movements voluntarily.

The corpus cavernosum recti contains no arterioles and no venules. It is a direct vascular connection from the branches of the afferent superior rectal artery and the efferent veins, without capillaries (functional circulation). The arterial terminal branches open directly into large spongy (lacunar) vessels. These vessels, in turn, drain the blood into the superior, middle, and inferior rectal veins (vena rectalis superior, media, and inferior) in a type of rope ladder system. This vascular structure (arterio-venous "short circuit") allows the build-up of considerable pressure in the blood vessels. On the surface of the hemorrhoidal plexus is an arterial vascular system that branches into smaller blood vessels and radiates into the interstitial spaces of the plexus. This vascular system supplies blood to the corpus cavernosum recti itself (nutritive circulation; nutritive = 'serving nutrition'). Hemorrhoids are cherry red because of the arterial blood supply. Only in the case of hemorrhoidal disease can a hemorrhoidal knot displaced in front of the anus change its color due to constriction. Due to the congestion of blood it then becomes blue-red and apparently venous.

III degree hemorrhoidal disease, in which the anatomical location of the main hemorrhoidal nodes at 3, 7 and 11 o'clock can be clearly seen

Schematic representation of the continence organ of a healthy person with opened sphincter. The corpus cavernosum recti is the anatomical starting point for haemorrhoids.

Distribution

Hemorrhoidal disease usually develops in the age range of about 45 to 65 years. Women and men are affected about equally often. Unusually, hemorrhoids develop before the age of twenty. Haemorrhoidal disease is a very common condition, which is why it is sometimes referred to as a "widespread disease". In Germany, there are about 3.5 million cases treated every year. About 50,000 operations are performed. It is estimated that in the western industrial nations there are about 1000 haemorrhoid-related doctor's visits per 100,000 people each year, which is 1% of the population per year. In addition, there is a high proportion of self-diagnosis and self-treatment that is almost impossible to record.

There are very different figures on the number of new cases (incidence) and the frequency of the disease (prevalence): In numerous specialist articles and reference books, very high figures are quoted across the board for the frequency of symptomatic haemorrhoids, which are in the range of 50% of the population. Symptomatic haemorrhoids are classified by some authors as the "most common disease of the rectum". Also, data can be found that about 70 to 80% of the population would experience hemorrhoidal complications during their lifetime. However, these figures are not based on epidemiological data, but on estimates by experts. The few epidemiological studies that do exist arrive at considerably lower frequencies. One reason for this is that a large number of anal complaints, such as anal eczema, are obviously attributed to symptomatic hemorrhoids.

There are also only a few studies on the prevalence of haemorrhoids. The authors of the guideline on haemorrhoidal disease of the German Society for Coloproctology of July 2008 even come to the conclusion: valid epidemiological studies on the prevalence of haemorrhoids are not available. The existing studies vary considerably in their results, which is mainly due to the study design, but also to the problem of determining the prevalence. Many patients initially 'sit out' the condition because of their sense of shame, try self-treatment or follow unqualified recommendations. A weakness of previous studies is that patients were asked verbally or in writing about symptoms for haemorrhoidal disease - which, however, can also occur with other conditions. For reliable data, a medical examination is essential.

In one study, for example, the medical records of a colorectal ward - i.e. a ward dealing with diseases of the colon and rectum - were evaluated. The authors of the study found a prevalence of 86% for asymptomatic and symptomatic haemorrhoids. This study was conducted in a very specifically selected group of patients. Systematic errors can therefore not be excluded. In 1990 a meta-analysis was published in which data from the National Health Interview Survey, the National Hospital Discharge Survey and the National Disease and Therapeutic Index of the United States and the Morbidity Statistics from General Practice in England and Wales were evaluated. The authors arrived at a prevalence of 4.4%, which corresponded to 10 million US citizens suffering from hemorrhoids. The maximum prevalence was in the age range of 45 to 65 years. In the aforementioned studies, hemorrhoids were neither classified as symptomatic or asymptomatic nor according to their stages.

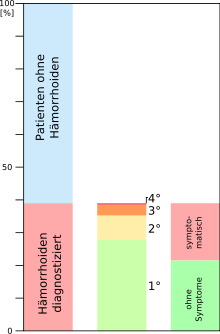

In September 2011, the results of a prospective study from 2008 and 2009 were published in which 976 patients in Austria were examined for hemorrhoids as part of colonoscopy for cancer screening at four different clinics. The hemorrhoids were classified according to a standardized system. A total of 380 patients (38.9%) were diagnosed with hemorrhoids. Considering only the 380 patients, the majority (72.9 %) had stage 1 hemorrhoids, 18.4 % had stage 2 hemorrhoids, 8.2 % had stage 3 hemorrhoids, and only 2 patients (= 0.5 %) had stage 4 hemorrhoids. Almost half (44.7 %) of the patients with diagnosed hemorrhoids complained of symptoms related to their hemorrhoids. Correspondingly, 55.3% were without symptoms. Calculated on all 976 patients of the study, 17 % complained of symptomatic hemorrhoids.

In another study, 548 patients with unclear symptoms in the abdomen and/or anus were interviewed and subsequently examined proctologically-colonoscopically. Sixty-three percent of the patients believed they had hemorrhoidal disease, 34% did not, and the remainder did not report it. However, on examination, hemorrhoids were detected in only 18 and 13% of these patients, respectively. The authors of the study conclude that hemorrhoids are too often suspected and treated.

In a 2010 Italian study, 116 patients were evaluated for asymptomatic and symptomatic hemorrhoids prior to their kidney transplant. 70.6% had no hemorrhoids. First degree hemorrhoids were found in 24% and second degree hemorrhoids in 5.4%. No patient had third or fourth degree hemorrhoids. After transplantation, 22.4% of the 116 patients developed third- and fourth-degree hemorrhoids. This was particularly the case in patients who had previously had hemorrhoids or who gained body weight rapidly after the transplant. The authors of the study suspect that immune-suppressive therapy after transplantation plays an important role in the worsening of hemorrhoidal disease.

African Americans are significantly less often affected than whites. In underdeveloped countries, hemorrhoidal disease is extremely rare.

The prevalence of hemorrhoids according to an Austrian study from 2011.

Questions and Answers

Q: What are hemorrhoids?

A: Hemorrhoids are vascular structures in the anal canal that aid in stool evacuation.

Q: What causes hemorrhoids to become swollen or inflamed?

A: Hemorrhoids become swollen or inflamed due to various factors such as chronic constipation, diarrhea, pregnancy, and straining during bowel movements.

Q: Are hemorrhoids a normal part of the anatomy?

A: Yes, hemorrhoids are a normal part of the anatomy.

Q: What is the function of hemorrhoids?

A: Hemorrhoids act as a cushion made of complex tissue that aids in the passage of stool.

Q: How common are hemorrhoids?

A: Hemorrhoids are very common, and nearly three out of four adults will have hemorrhoids from time to time.

Q: What are hemorrhoids commonly referred to as?

A: Hemorrhoids are commonly referred to as piles.

Q: Can hemorrhoids be prevented?

A: Yes, hemorrhoids can be prevented by maintaining good bowel habits, avoiding straining during bowel movements, exercising regularly, and eating a high-fiber diet.

Search within the encyclopedia