Hellenistic period

![]()

Hellenismos is a redirect to this article. For the neo-pagan movement of the same name, see Hellenismos (religion).

Hellenism (from Greek Ελληνισμός hellēnismós 'Greekness') is the term used to describe the period of ancient Greek history from the accession of Alexander the Great of Macedon in 336 BC to the incorporation of Ptolemaic Egypt, the last major Hellenistic empire, into the Roman Empire in 30 BC.

However, these epochal boundaries, which focus on the Alexander Empire and the successor empires of the Diadochi, only make sense for political history, and even for this only to a limited extent, because by the middle of the 2nd century BC most Greeks had already come under the direct or indirect rule of the Romans or Parthians. In terms of cultural history, on the other hand, Hellenism not only picked up where older developments left off, but also continued to have an effect, especially beyond the Roman imperial period and into late antiquity. Angelos Chaniotis therefore places the epochal boundary only at the death of Emperor Hadrian in 138 AD: he had completed the integration of the Greeks into the Roman Empire.

The German historian Johann Gustav Droysen first used the term "Hellenism" around the middle of the 19th century. He understood Hellenism as the period from the death of Alexander the Great (323 BC) to the Battle of Actium (31 BC) and the end of the last Greek empire in Egypt. However, in the sense of "imitating the Greek way of life", the noun "hellenismós" and the verb "hellenizein" were already used in antiquity. It is derived from Hellenes, the proper name of the Greeks.

An important characteristic of this historical epoch is considered to be an increased Hellenization, the penetration of the Orient in particular by Greek culture, and in turn the growing influence of Oriental culture on the Greeks. The Hellenistic world encompassed a vast area that stretched from Sicily and lower Italy (Magna Graecia) to Greece and India, and from the Black Sea to Egypt and present-day Afghanistan. The Hellenization of the Oriental population ensured that, as late as the 7th century, a form of Greek was still used alongside Aramaic, at least by the urban population of Syria, the Koine (from κοινός koinós "general"), which persisted considerably longer in Asia Minor. The cultural traditions of Hellenism survived the political collapse of the monarchies and continued to have an effect for centuries in Rome and the Byzantine Empire.

With Alexander the Great the time of Hellenism began (Tetradrachmon, Alexander with lion skin)

Historical outline

→ Main article: History of Hellenism

The Macedonian king Alexander III "the Great", under whose father Philip II. Macedonia had become the hegemonic power over Greece, conquered from 334 BC on the Persian Achaemenid Empire (Alexander campaign) and advanced to India. After Alexander's death in 323 BC, civil wars broke out over his succession. Since no one succeeded in gaining rule over the entire empire, his leading generals, the so-called Diadochi, eventually rose to local power. From 306/5, most of them held the title of king. A reunification of the Alexander Empire seemed hopeless in 301 BC at the latest, when Antigonos I Monophthalmos was defeated by his rivals in the Battle of Ipsos. The so-called diadochal struggles for Alexander's inheritance finally ended in 281 BC after a total of six wars. Three major Hellenistic empires were formed, which were to dominate the eastern Mediterranean until the 2nd century BC and were ruled by Macedonian dynasties: Macedonia proper and large parts of Greece fell to the Antigonids, the descendants of Antigonos I; Asia Minor, Syria, Mesopotamia, and Persia came under the rule of the Seleucids; and Egypt, Cyrenaica, and the Levant fell to the Ptolemies. All three dynasties also rivalled for influence in the Aegean region and never gave up their pro forma claim to Alexander's overall empire. In addition, there were middle powers such as Attalid Pergamum, Rhodes, and the Achaian League.

After the end of the diadochal wars, the political situation initially stabilized as the three great empires neutralized each other. From 200 BC, however, Rome began to become involved in the Hellenistic world, first in Greece, then in Asia Minor, and also intervened in the Seleucids' conflict with the Ptolemies over Palestine. In 188 BC, the Romans forced the Seleucid Antiochos III to renounce parts of his empire; he had to give up most of Asia Minor. Philip V of Macedonia had already had to accept a narrowing of his scope of action in Greece and Asia Minor after the smaller states of the region, such as Pergamum, which feared for their independence because of Antiochus' and Philip's expansionist aspirations, had provided the Romans with pretexts for military intervention, which resulted in an initially indirect regional hegemony of Rome. At the latest since the Day of Eleusis in 168 BC, when the Seleucid Antiochos IV had to abandon a victorious campaign against the Ptolemies on Roman instructions, the new balance of power was obvious.

These severe setbacks were not without consequences for the monarchies, whose existence rested largely on the military prowess of the kings: In Iran, until then under Seleucid control, the Parthians had already been spreading since the 3rd century BC, ruled by the Arsakids, who initially presented themselves to the West as heirs to the Hellenistic tradition. After 188 BC, their advance accelerated considerably. When the Arsacids also took possession of Mesopotamia around 141 BC, they confined the Seleucids, who had already lost their eastern territories to the Greco-Bactrian kingdom in the 3rd century, to an insignificant remnant state in Syria. The Hellenistic kings in Bactria, on the other hand, whose empire fell around 130 BC, had previously extended their sphere of influence to northwest India, where Greek monarchs were able to hold on at least until the end of the 1st century BC.

In 168 BC, after a final war, the Romans divided Macedonia into four districts and abolished the Antigonid monarchy; in 148 BC they finally transformed it into a Roman province and stationed troops permanently in the region for the first time. The Greek motherland thus also finally came under Roman control; a signal event was the conquest and sack of Corinth by the general Mummius in 146 B.C. In 133 B.C. the Attalid Empire fell to Rome and soon afterwards became the province of Asia. Around 88 BC, Roman hegemony was challenged for the last time when many Greeks aligned themselves with King Mithridates VI, but he was eventually defeated by Rome. In 63 BC, Pompey's annexation of Syria eliminated the last remnants of Seleucid rule; in 30 BC, Octavian took Alexandria and incorporated the Ptolemaic Empire, which had been little more than a Roman protectorate since the late 2nd century BC anyway, into the empire. In 27 BC, Greece was finally also subordinated to direct Roman rule as the province of Achaea, even though some poleis in Hellas and Asia Minor remained outwardly free. This ended the political independence of Greek states for almost two millennia, and thus also the political history of Hellenism, while the cultural aura of Hellenism remained until late antiquity (see also Byzantine Empire).

The world empire which had come into being on the march of Alexander, and which he bequeathed to his successors in 323 B.C.

The Hellenistic World 300 BC.

The Hellenistic World 200 BC.

Hellenistic monarchies

The kingship of the Hellenistic rulers stood on two pillars: the succession of Alexander (διαδοχή, diadochē) and the acclamation by the armies (see below). States did not exist independently of their form of government in this regard; the Seleucid rulers, for example, were not kings of Syria, but kings only in Syria; one reason for this may have been that each Hellenistic basileus theoretically laid claim to the whole of Alexander's empire, if not to the whole world. In the Diadochan empires there was no separation between sovereign and person. Kingship (basileia) was not a state office but a personal dignity, and the monarch saw the state, which was not conceptually distinct from it, as his affairs (pragmata). Theoretically, all conquered land was in the possession of the king, which is why he could also transfer it by will to a foreign power such as the Romans (as happened in 133 BC in Pergamon).

Initially, the military successes of the Diadochi in their participation in Alexander's campaigns were sufficient to gain charisma and legitimacy. However, due to the lack of kinship between the Diadochi and the Argeads, a problem of legitimacy arose. Since military excellence was the first means of legitimation, the Diadochi tried to tie in with Alexander's military genius in an idealistic way as well. Even the possession or burial place of Alexander's body, for which there was fierce competition, and his insignia of rule, such as his signet ring, served to legitimize him. Most importantly, the cult of personality that had developed around Alexander was promoted by the Diadochi to legitimize their own position of power. The problem of legitimacy became more acute in the second generation. Therefore, in the course of a strategic marriage policy with the female members of the Argeads, genealogy was used as a central means of legitimation. In part, relationships with the Macedonian ruling house or a sonship with God were simply invented. Thus, for example, the rumor arose that Ptolemy was a half-brother of Alexander. All in all, the changes of throne rarely went smoothly; often competing pretenders to the throne were eliminated.

The Diadochi had their portraits, adorned with cultic symbols such as bulls' or rams' horns, placed on the obverse of the coins, where traditionally the portraits of the gods found their place. Ammon horns were already used in the iconography of Alexander the Great and established a connection with the divine sphere. They were adopted by the Diadochi initially for the purpose of their legitimation. The cultic worship of the Hellenistic rulers was, however, at least initially not demanded by them themselves, but was brought to them from outside, by the "free" poleis of Greece. Unlike in Macedonia and in the former territories of the Persian Empire, monarchy was fundamentally rejected in Greece, which forced kings and subjects alike to be diplomatically adroit. One way of casting the de facto supremacy of kings into an acceptable form was the ruler cult, through which the poleis could recognize kings as lords without accepting them de iure as monarchs. Here one could fall back on precursors from late classical times (e.g. Lysander). For the time being, the rulers were only called "godlike". But as early as 304 BC the Rhodians referred to Ptolemy I as a god and called him σωτήρ (Sōtēr, "savior"). The Diadochi apparently adopted such cult acts, related to themselves, rather hesitantly, while subsequent Hellenistic kings deliberately pushed the cult of rulers, partly in order to build dynasties. The typical Hellenistic ruler cult began, after precursors under the first two Antigonids, on a broad front under their successors. A distinction must be made between the centrally decreed dynastic cult of the Ptolemies and late Seleucids and the cultic veneration that many kings enjoyed in the Greek poleis, to whom they in return were euergetes.

Hans-Joachim Gehrke in particular, drawing on Max Weber's sociology, has interpreted the Hellenistic monarchy as a strongly charismatic form of rule in which victoriousness and personal success were decisive for the legitimacy of the king. The ruler's costume was that of a Macedonian commander, supplemented by the diadem, and many kings went into battle personally, with the corresponding consequences: 12 of the first 14 Seleucid rulers died in battle. More recently, it has been pointed out that it became increasingly difficult to live up to this claim in late Hellenism. These interpretations, however, have not gone unchallenged; some scholars consider them at best applicable to the Diadochi, others not at all.

The diadochi and their successors ruled by means of written decrees, which were formulated as letters (ἐπιστολή, epistolē) or ordinances (πρόσταγμα, prostagma). The official in charge of these decrees was called epistoliagraphos. The ruler was advised by a body of friends (φίλοι, philoi) and relatives (συγγενεῖς, syngeneis). Various court offices, especially in the fiscal sphere, were held by eunuchs. Probably the most important office was that of steward (διοικητής, dioikētēs), who was responsible for administration, economy, and finance. One can already speak of an "absolutist" state at the time of the Diadochi. The form of rule of the Hellenistic empires gained decisive influence on the younger Greek tyranny, the Carthaginians and the Roman emperorship.

The territorial structure of the diadochic empires can still be traced back to Alexander the Great himself, who had essentially retained the administrative structure of the Persian Empire. The royal lands administered by strategists and satraps comprised the largest part of Alexander's empire. Alexander had handed over the military powers of the native satraps to Macedonian strategists, who after his death gradually took over the entire administrative work of their gaue (νόμοι, nomoi). The strategists were now also responsible for settlement and justice, and were assisted by a royal scribe (βασιλικὸς γραμματεύς, basilikos grammateus).

Here one is particularly well informed about the conditions in the Ptolemaic Empire, which, however, was partly a special case. Here the king could assign parts of the royal land, which was subdivided into districts (τόποι, topoi) and villages (κώμαι, kōmai), or the revenues from them to his subjects. Gau administration found its final form in the 3rd century B.C. under Ptolemy III. (246–221). The outlying possessions did not belong to the king's country with its Gau structure. They formed a separate type of territory, but were also under the control of strategists. The external possessions of the Ptolemaic Empire included Cyrene, parts of Syria and Asia Minor, Cyprus, and the coasts of the Red and Indian Seas.

In the Seleucid Empire the outlying possessions were organized somewhat differently; they were called peoples (ἔθνη, ethnē), cities (πόλεις, poleis), or kingdoms (δυναστεία, dynasteia), depending on their size and political system. These enclaves, which were not under the direct administration of the diadochal ruler, continued in this form until the end of Hellenism. Some of them, however, made themselves independent in the course of time, especially on the periphery of the Seleucid Empire. In the third great Hellenistic empire, Macedonia, the Antigonids drew more closely on older traditions than the other monarchs.

More than their structure, the administration of the Diadochan empires has influenced posterity. As a rule, it was centralized and organized by professional officials. This civil service was not an invention of Greek polar culture, but was in the tradition of the Achaimenid and Pharaonic empires. In ancient Greece, comparable systems existed only in the private estate administration. As the employees of an estate depended on its owner, so the officials of the Hellenistic rulers depended on their king, who appointed, paid, promoted, and dismissed them. The administration of the diadochi laid the foundation for the finely chiseled and personnel-intensive bureaucracy of the Hellenistic period, though native officials were rarely admitted to higher offices. These were usually filled by Macedonians or Greeks.

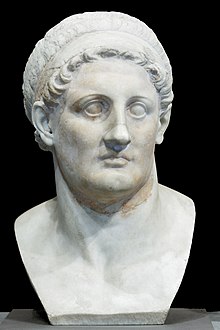

Ptolemy I was one of the first Hellenistic rulers to be worshipped as a god

Search within the encyclopedia