Heinrich Brüning

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Heinrich Brüning (disambiguation).

Heinrich Aloysius Maria Elisabeth Brüning (* 26 November 1885 in Münster; † 30 March 1970 in Norwich, Vermont, USA) was a German politician of the Centre Party and Reich Chancellor from 30 March 1930 to 30 May 1932.

The conservative-national Catholic had become leader of his party's parliamentary group in the Reichstag in 1929 and in this capacity supported Hermann Müller's Grand Coalition. The day after the resignation of the Müller cabinet (27 March 1930), he was appointed by Reich President Hindenburg to form a new government - the first of the so-called presidential cabinets that did not result from a coalition of the parties represented in the Reichstag. Brüning was the last chancellor of the Weimar Republic to govern on a constitutional basis. His "Brüning System" was based on so-called emergency decrees issued by the Reich President, which increasingly replaced the normal legislation of the Reichstag. In May 1932, Hindenburg dropped Chancellor Brüning because he was still dependent on the parliamentary toleration of the Social Democrats.

Brüning was unpopular as chancellor because of his austerity measures to combat the Great Depression of the 1930s. Whether these measures served to free Germany from its reparations obligations, as they did a few weeks after his resignation, is disputed in research. Brüning's attitude toward the National Socialists vacillated between fighting and incorporating the NSDAP into a right-wing coalition. In July 1933, as chairman, he wound up the Zentrum as the last democratic party. In 1934 he fled Germany; the rest of his life was spent mainly in the United States, where he taught at universities, between 1951 and 1955 briefly back in Germany.

His memoirs, which were published posthumously in 1970, caused a sensation. Opinions differ among historians as to their value as sources.

Heinrich Brüning, around 1930

Youth, study and war experience

When Brüning was one year old, his father, a conservative Catholic vinegar manufacturer and wine merchant, died. His older brother Hermann Joseph had a great influence on his later education.

Brüning attended the Gymnasium Paulinum in Münster. He first studied law at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. On 8 May 1904 he joined the CV fraternity KDStV Langobardia. In 1906, however, he then moved to Strasbourg, where he took philosophy, history, German studies and political science. There he became a member of the KDStV Badenia and the KDStV Rappoltstein. In 1911 he passed the state examination for the higher teaching profession, which he did not take, however. Instead he turned to the study of national economy. For this purpose he enrolled at the University of Rostock in May 1911. He then went to England to study national economics at the London School of Economics and Political Science. In 1913 he transferred to the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Bonn, where he completed his unusually long course of study in 1915. He obtained his doctorate with a dissertation on The Financial, Economic, and Legal Condition of the English Railways with Reference to the Question of Their Nationalization. He had collected all the material for his thesis on the spot in England. When he volunteered for the infantry in the First World War in 1915, he stated a university career as his career goal.

Brüning, whose weak physical constitution and short-sightedness had given cause for concern at the muster, rose to the rank of lieutenant of the reserve in the infantry regiment Graf Werder No. 30. Because of his bravery he was awarded the Iron Cross II. and I. class. After being wounded for the second time, Brüning enlisted in the newly formed MG Scharfschützen Abt. 12 in 1917, eventually advancing to company commander and earning the respect of the soldiers under his command. This was reflected in Brüning being elected to a soldiers' council after the armistice. These Soviet Russian-style councils were supposed to represent the interests of ordinary soldiers to their superiors. Despite his involvement in the Soldiers' Council, however, Brüning was an opponent of the November Revolution, a fact which he also expressed as Chancellor of the Reich.

Political career

Ascent

Brüning never spoke much about his personal life. Nevertheless, Hans Luther, who worked closely with him when he himself held the position of Reichsbank president, suspects that his experiences on the front had made him change his professional goals. Instead of an academic career, he now aimed for a political one after the end of the war. In 1919 he became an associate of the Catholic social politician Carl Sonnenschein and helped discharged soldiers in their studies and careers. Six months later, the Prussian Minister of Welfare, Adam Stegerwald, made him his advisor. Stegerwald also headed the German Trade Union Federation (DGB), of which Brüning became executive director in 1920. From 1924 he was a member of the Reichstag and quickly rose to become the financial policy spokesman for the centrist faction. In 1925 he achieved with the so-called lex Brüning that the wage tax was limited to 1.2 billion Reichsmark. His expertise earned him a reputation, although his personal reserve and taciturnity made it difficult to deal with the ascetic-looking bachelor. He was also a member of the Prussian parliament from the state election in May 1928 until his resignation on July 12, 1929.

In 1929 he became parliamentary group leader of the Centre Party in the Reichstag and pushed through the so-called "junction": His party would only agree to the Young Plan if at the same time the budget was balanced by tax increases and austerity measures. This consistently advocated policy also attracted the attention of the Reich President. Contrary to his plans, however, Brüning worked within the Grand Coalition (Müller II Cabinet) towards a compromise between the SPD and the German People's Party (DVP). But since the Social Democrats knew that the Reich President wanted to force them out of the government and that after agreeing to Brüning's final compromise proposal the DVP and industry would only demand further concessions from them, they refused. On this the Grand Coalition broke up. On 27 March 1930 the Müller cabinet resigned.

Appointment as Reich Chancellor

Even before that, the Reichswehr leadership had been looking for a conservative successor to the Social Democratic Reich Chancellor Hermann Müller in Kurt von Schleicher and Paul von Hindenburg. Their choice quickly fell on Brüning. His appointment "was not unexpected by political observers. Since Easter 1929, but increasingly since the turn of the year 1929/30, Brüning had been the Reichswehr Ministry's candidate for chancellor and a conservative politician for a bourgeois government. [...] Not only the composition of Brüning's cabinet, but also Hindenburg's order to the Reich Chancellor-designate not to 'build the government on the basis of coalition ties' clearly showed that the political weights were to be shifted to the right."

The day after Müller's resignation, Heinrich Brüning was commissioned by Reich President Hindenburg to form a new cabinet. Two days later he took office as the twelfth Chancellor of the Weimar Republic. The cabinet was formed in record time: as early as April 1, Brüning was able to present his government, the Brüning I cabinet, to the Reichstag. In addition to politicians from the Centre, the DDP, the DVP and the Economic Party, the cabinet also included Martin Schiele, a representative of the anti-constitutional DNVP, who, however, left the party in July 1930 in the wake of the second wave of secession. Hindenburg hoped to finally have the "anti-parliamentary" and "anti-Marxist" cabinet he had worked on in the background talks of the months before together with Kuno Graf Westarp, Gottfried Treviranus and Kurt von Schleicher. Immediately in his government declaration, Brüning made it clear to Parliament that he was willing to work against it if necessary: The era of the non-parliamentary but constitutionally compliant "presidential cabinets" began.

The first task of the new cabinet was to balance the deficit-ridden budget. Although the effects of the Great Depression had not yet reached their peak in Germany, the Young Plan demanded the stability of the German currency in addition to other high reparation claims. The Reichsmark was therefore not allowed to be devalued, nor was the economy to be boosted with economic stimulus programmes.

Brüning's first reorganization program, which from June 20 to 26, 1930, also provisionally headed the Reich Ministry of Finance, was rejected by the Reichstag: Contrary to Hindenburg's hopes, Brüning had not succeeded in wresting a sufficiently large number of DNVP deputies from the radical party leader Alfred Hugenberg and drawing them into the government camp. As the chancellor had threatened, he now pushed through the cover bills with an emergency decree under Article 48 of the constitution, but a parliamentary majority of SPD, KPD, the radical wing of the DNVP around Hugenberg, and the NSDAP rescinded the emergency decree on July 18. Thereupon Brüning read out the dissolution order of the Reich President in accordance with Article 25. The Centre, the liberal parties and the moderate wing of the DNVP around Count Westarp, who left the party in July, had voted against the repeal of the emergency decree - in order to avoid a dissolution of the Reichstag and the resulting new elections at this highly inopportune time. The Reichstag election was scheduled for September 14, 1930.

In the election campaign Brüning tried to activate the large "party" of non-voters and first-time voters and counted on strengthening the governmental-conservative dissidents from the DNVP, now organized in various small parties, who were represented in his government by Schiele and Treviranus. Five million previous non-voters actually voted as well. The NSDAP, and to a lesser extent the KPD, saw a significant increase in votes. The National Socialists increased the number of their seats from 12 to 107 and thus became the second strongest parliamentary group. Although the DNVP also lost half of its voters, only a small number of them went to the smaller parties that had emerged from the splits. German values on foreign stock exchanges fell sharply in response to the election results, and foreign loans were withdrawn. The world economic crisis, which had been felt since the summer, intensified noticeably.

For Brüning, the election results were tantamount to a catastrophe: instead of a balanced budget, ever new deficits due to the worsening depression; instead of a stable "Hindenburg majority" between the SPD and the National Socialists, a Reichstag incapable of forming a stable majority. Germany was now politically and economically in a serious emergency, which paradoxically had been triggered by the very emergency measures that were supposed to have eliminated them.

Chancellor of the Reich in times of crisis

In long negotiations, Brüning succeeded in persuading the Social Democrats to form a "toleration coalition", pointing out that the next new elections would be even more disastrous for democracy in Germany. Brüning subsequently introduced hardly any legislation into the increasingly infrequently convened Reichstag, instead issuing emergency decrees (62 in all during his term). Communists or National Socialists then always moved a motion to repeal them, but each time it was defeated by the votes of the governing parties and the SPD. Thus the SPD did not vote for Brüning's emergency decrees, it merely prevented their repeal. This enabled Brüning to govern in a stable manner during a stormy period, even if the Reich President was not very pleased about this renewed dependence of "his" government on the Social Democrats.

Brüning pursued a drastic policy of austerity and deflation in a total of four major emergency decrees: he imposed new taxes while cutting state benefits, and he worked to lower wages and salaries. In this way he hoped to increase German exports, but because Germany's trading partners pursued similar policies and also raised their tariffs, this procyclical policy was bound to fail; in the end it only exacerbated the economic crisis in Germany.

Many historians assume that Brüning also pursued his harmful economic policy in order to end the reparations: He had thereby wanted to prove to the Allies that Germany was not in a position to pay the reparations despite its utmost efforts. That this "primacy of reparations policy" really existed is doubted. Afterwards, Brüning and his colleagues certainly believed that they could overcome the financial crisis with their deflationary policy and prevent a renewed inflation.

In the spring of 1931, the plan for a customs union with Austria met with fierce resistance from the French, who saw it as an attempt to circumvent the "Anschluss" ban of the Treaty of Versailles in the medium term. This was not the first time that the death of Gustav Stresemann in October 1929 had revealed a major gap in German foreign policy. To torpedo the plan, the Laval government encouraged the French banks to withdraw money from Germany and Austria. Now the German banks were in trouble, which was compounded after a second foreign policy blunder by Brüning: to make the next antisocial austerity package palatable to the German public, the government issued an appeal in June 1931 in which, following radical right-wing language, it called the reparations "tributes" and hinted that Germany would not be able to pay for much longer. A simultaneous courtesy call on the British government gave the impression that a reparations policy move was imminent. Since, after the experience of the Ruhr struggle of 1923, a reparations policy conflict threatened to affect the stability of foreign investment, credit withdrawals intensified to the point of panic. In parallel with these foreign policy efforts, a new emergency decree went into effect in early June, further reducing pensions for the disabled and war-disabled, as well as civil servants' salaries and unemployment benefits. The emergency decree triggered massive protests, especially on the part of the KPD, with demonstrations and so-called hunger marches.

In order to avoid a complete collapse of the German economy and to restore confidence in Germany's ability to at least pay its private foreign debts, on June 20, 1931, U.S. President Herbert Hoover proposed a moratorium on both German reparations and inter-Allied war debts, which Britain and France in particular were repaying to the United States with reparations money. Weeks of negotiations with the French followed, which caused the psychological effect of the generous proposal to fizzle out.

Foreign loans were further withdrawn, and on July 13, 1931, all major German banks were forced to close for several days. This blow to the economy resulted in a sharp rise in unemployment. In February 1932, 6 million Germans were officially unemployed, and probably as many as 8 million in real terms. 37% of the working population was out of work, and on average each family had one unemployed person. For reparations policy, however, the catastrophe of the German economy was favorable, for now the British saw that without a substantial reduction or cancellation of reparations, confidence in German creditworthiness would not return. This thesis, however, did not prevail until the summer of 1932, after Brüning's dismissal, at the Lausanne Conference, which brought the de facto cancellation of reparations in return for a balance payment of three billion gold marks, which also never materialized. Immediately before the end of the Brüning government's term, it bought a block of shares in Gelsenberg-AG from Friedrich Flick with a nominal value of RM 100 million. This transaction went down in history as the Gelsenberg affair.

Fall

Brüning gradually lost the support of Hindenburg, who had in mind a purely right-wing cabinet without any SPD support. In vain he warned the aged Reich president urgently "not to make the most serious political mistake that anyone would be in a position to make at the moment ... and not to lose his cool"; he implored the Reichstag on 11 May 1932 that he was "a hundred yards from the goal". When the French ambassador André François-Poncet drew his attention to the fact that the goal he himself had announced a few weeks earlier, the complete cancellation of all German reparations obligations without replacement, would certainly not be achieved in Lausanne, Brüning only said laconically that "in judging the distance from the goal, it is the overall distance that counts". The assurance of victory in reparations policy on the part of the chancellor, who had also headed the Foreign Ministry since October 1931, was a tactic motivated by domestic politics.

Since the spring of 1932, Hindenburg had become increasingly disappointed with Brüning, on whom he had placed great hopes. This was not changed by the fact that the chancellor had helped the 83-year-old to re-election on 10 April 1932 in a restlessly fought election campaign. That Hindenburg owed this success to Catholics and Social Democrats of all people, the old Bismarckian "enemies of the Reich", who considered the monarchist field marshal the lesser evil compared to his opponent Hitler, he personally resented Brüning. Hitler had been supported by many of Hindenburg's old companions and even by the former Crown Prince.

The rift between the two was deepened by the ban on the SA, which Interior and Defense Minister Wilhelm Groener had issued on April 13, 1932. This had brought Hindenburg into conflict with the Reichswehr leadership under his friend Schleicher, who intended to use the SA as a recruiting pool for military rearmament. It was hoped that the victorious powers would concede it to Germany at the Geneva Disarmament Conference. Schleicher's intrigues led to Groener's resignation on May 13, 1932, and also weakened Brüning.

In the spring of 1932, the Brüning government was working on a fifth major emergency decree, which would have possibly exacerbated unemployment. Therefore, plans were discussed to enable a subsistence economy by settling a certain number of unemployed in the countryside and thus to clean up the statistics. Behind this was the conviction that Germany would not recover from the Great Depression in the long run - instead of economic growth and the creation of new jobs, Brüning was counting on a return to an agrarian society. The land for the army of millions of new settlers was to be obtained by ending aid to the East. This involved subsidies for the over-indebted large agricultural estates in eastern Germany, which had hitherto always been spared the government's austerity measures. After the subsidies for some farms had in the meantime exceeded their value several times over and the Reich budget was once again on the verge of insolvency, provision was made for an end to permanent subsidies for estates that were not capable of debt relief. In the compulsory auction that inevitably followed, the estates were to be acquired by a state-owned Auffanggesellschaft and resettled with the unemployed. This led to furious protests by the East German agrarians and their conservative friends. A resolution of the DNVP faction in the Reichstag called the plan "consummate Bolshevism." In this climate Hindenburg, who as owner of Gut Neudeck himself had a personal interest in Eastern aid, announced on 29 May 1932 that he would no longer sign any of his emergency decrees. Brüning resigned on 30 May 1932 and received his certificate of dismissal in an undignified short ceremony. Subsequently, this conflict went down in history with the term Osthilfeskandal.

Since Brüning, as a bachelor, had no apartment of his own, he retired to the Catholic St. Hedwig Hospital after moving out of his official residence in Wilhelmstraße. The rooms provided by the matron there accommodated him until, after the Enabling Act was passed, the hospital administration was threatened that it would face the full rigors of the new government. Brüning then went underground, changing homes daily, and then into exile in the United States via the Netherlands.

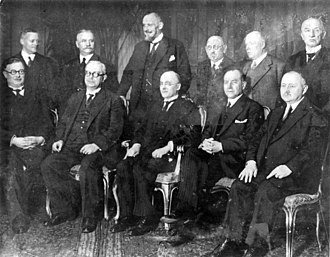

The Brüning I Cabinet on 31 March 1930: f. l. t. r. seated Minister of the Interior Joseph Wirth (Center), Minister of Economics Hermann Dietrich (DDP), Reich Chancellor Brüning, Minister of Foreign Affairs Julius Curtius (DVP), Minister of Posts Georg Schätzel (BVP), standing Minister for the Occupied Territories Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus (Conservative People's Party), Minister of Food Martin Schiele (DNVP), Minister of Justice Johann Viktor Bredt (Economics Party), Minister of Labor Adam Stegerwald (Center), Minister of Finance Paul Moldenhauer (DVP), Minister of Transport Theodor von Gerard (Center). Reichswehr Minister Wilhelm Groener is missing from the picture.

Brüning at the Corpus Christi procession in Berlin in May 1932

Search within the encyclopedia