Heilbronn

![]()

This article is about the city. For other meanings, see Heilbronn (disambiguation).

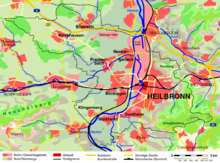

Heilbronn [haɪ̯lˈbrɔn] is a large city in the north of Baden-Württemberg and, with 126,458 inhabitants, the seventh largest city in the state. The city is located on the Neckar River, about 50 kilometres (31 mi) north of the state capital Stuttgart, is its own city district and is also the seat of the district of Heilbronn, which completely surrounds it. Heilbronn is also the upper centre of the Heilbronn-Franconia region (until 20 May 2003 Franconia region), which encompasses the north-east of Baden-Württemberg, and is part of the fringe of the European metropolitan region of Stuttgart. The area around Heilbronn is usually called the Unterland in the wider region.

First mentioned in 741, Heilbronn gained the status of an imperial city in 1371 and, due to its location on the Neckar, developed into an important trading centre from the late Middle Ages onwards. At the beginning of the 19th century Heilbronn became one of the centres of early industrialisation in Württemberg. Heilbronn's old town was completely destroyed in the air raid of 4 December 1944 and rebuilt in the 1950s. Most of the buildings in the city centre today date from this period.

Heilbronn is known as the city of wine because of its extensive vineyards. The city is also called Käthchenstadt, after the name of the title character in Heinrich von Kleist's play Das Käthchen von Heilbronn.

On 1 February 2020, the Ministry of the Interior of Baden-Württemberg awarded the city of Heilbronn the designation of university city.

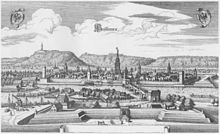

View over the Heilbronn city centre in the direction of Wartberg

Geography

Geographical position

Heilbronn is located in northern Baden-Württemberg in the fertile valley area of the Heilbronn Basin created by the Neckar River, a northern offshoot of the Neckar Basin. In the west, the comparatively less hilly Gartacher Feld adjoins. In the east, the Heilbronn Mountains surround the city from north to south as foothills of the Löwenstein Mountains, on whose slopes are extensive vineyard landscapes; these include the elevations Büchelberg, Galgenberg, Gaffenberg, Hintersberg, Reisberg, Schweinsberg and Wartberg. To the north of these lies the Sulmer Bergebene.

The highest point of the urban area is the 378 m high Reisberg in the extreme south-eastern tip of the Stadtwald, the second highest point is the 372.8 m high Schweinsberg. The lowest point of the district is 151 m at the Neckar at the border to Neckarsulm. The city area extends in north-south direction over 13 kilometres, in east-west direction over 19 kilometres. Heilbronn is part of the three natural areas Neckar Basin, Kraichgau and Swabian-Franconian Forest Mountains.

The Heilbronn dialect is a variant of the South Franconian dialect in the transition zone to the Alemannic dialect group.

Geology

Heilbronn is located in the northern part of the diversely dissected Southwest German strata. A deep borehole drilled in 1912/13 in the neighbouring town of Heilbronn, Erlenbach, at 163.68 m a.s.l. down to a depth of 856 m and supplemented by seismic investigations in 1954/56 provided information about the rock composition in the Heilbronn area. The surface of the original Variscan basement, composed of gneisses and granites, lies at 1080 to 1100 m below sea level. Above this lie layers of sedimentary rocks several hundred metres thick, first of all those of the Permian (about 390 m Rotliegend, 23.6 m Zechstein), followed by those of the Triassic: 517.2 m of Buntsandstein (about 80 m of Lower Buntsandstein, 370 m of Middle Buntsandstein, 67 m of Upper Buntsandstein), about 238 m of Muschelkalk (72.7 m of Lower Muschelkalk, 86.1 m of Middle Muschelkalk, 78.7 m of Upper Muschelkalk) and finally Keuper (27.5 m of Lower Keuper, 25.7 m of Middle Keuper). In the Middle Muschelkalk, a rock salt deposit up to 45 m thick is deposited in the north of the core city and in the northwest of the city area, which is exploited by mining.

With the Middle Keuper, the level of the Neckar is almost reached, which divides the city area from south to north. In the floodplain, which includes large parts of Heilbronn's industrial area and the western part of the city between the Altneckar and the Neckar Canal, it is overlain by an approximately three-metre-high blanket of the floodplain gravel deposited by the Neckar, which in turn is covered by approximately three metres of alluvial loam. Further away from the river are gravel layers that are only five to ten metres thick under the core city, but reach up to 35 metres in the west of the urban area between Böckingen, Frankenbach and Neckargartach. Almost everywhere there is still a 6 to 13 metre thick layer of blown, fertile loess and loess loam on top of them.

The Heilbronn Hills in the east of the city area, which are not covered by river deposits, reflect the further geological sequence of layers that have been removed by erosion in the rest of the city area. 28 to 29 metres of Lower Keuper are followed by 130 to 150 metres of Gipskeuper (Grabfeld Formation) and a layer of reed sandstone about 20 to 45 metres thick, which used to be exploited in quarries and whose brown-yellow Heilbronn sandstones used to characterise the Heilbronn townscape. The three highest mountains in the southeast of the city area, the Reisberg (378 m above sea level), the Schweinsberg (372.8 m above sea level) and the Hintersberg (364.8 m above sea level), carry above them the higher layers of the Untere Bunten Mergel and the Lehrberg layers (together around 32 to 35 metres) as well as Kieselsandstein (5 to 16 metres).

Neighboring communities

Starting in the north and listed clockwise, the cities of Bad Wimpfen and Neckarsulm, the community of Erlenbach, the city of Weinsberg, the communities of Lehrensteinsfeld, Untergruppenbach, Flein and Talheim, the city of Lauffen am Neckar, the community of Nordheim, the city of Leingarten, the city of Schwaigern, the community of Massenbachhausen and the city of Bad Rappenau border Heilbronn. All neighbouring towns and communities are in the district of Heilbronn. Heilbronn has grown together with Neckarsulm to form a closed settlement area.

City breakdown

→ Main article: List of places in Heilbronn

| District | Incorporation | Inhabitants | Area | Postcode(s) | Area code |

| Heilbronn | - – | 61.801 | 31,334 km² | 74072, 74074, | 07131 |

| Biberach | January 1, 1974 | 05.115 | 10.582 km² | 74078 | 07066 |

| Böckingen | June 1, 1933 | 23.292 | 11,353 km² | 74080 | 07131 |

| Frankenbach | April 1, 1974 | 05.786 | 8.889 km² | 74078, 74080 | 07131 |

| Horkheim | April 1, 1974 | 04.052 | 4,852 km² | 74081 | 07131 |

| Kirchhausen | July 1, 1972 | 03.936 | 11,471 km² | 74078 | 07066 |

| Klingenberg | January 1, 1970 | 02.436 | 2,721 km² | 74081 | 07131 |

| Neckargartach | October 1, 1938 | 09.839 | 11.249 km² | 74078 | 07131 |

| Sontheim | October 1, 1938 | 12.021 | 7,400 km² | 74074, 74081 | 07131 |

The urban area of Heilbronn is divided into nine districts. In addition to Heilbronn itself, these are the formerly independent communities of Biberach, Böckingen, Frankenbach, Horkheim, Kirchhausen, Klingenberg, Neckargartach and Sontheim.

Some districts include other places in the geographical sense such as individual farms and residential areas. In detail these are to Biberach the farms Konradsberg, to Frankenbach the Hipfelhof and to Neckargartach the Altböllinger Hof, Neckarau and the Neuböllinger Hof.

Departed, today no longer existing villages are Hetensbach and Rühlingshausen in the district of Böckingen, Utenhusa in the district of Biberach, Altböckingen, Hanbach and Rappach in the district of Heilbronn, Böllingen and Trapphof in the district of Neckargartach as well as Ascheim and Widegavenhusa in the district of Kirchhausen.

Böckingen, Frankenbach and Neckargartach belonged to Heilbronn as Imperial City villages until the beginning of the 19th century. Böckingen and Neckargartach were reincorporated in 1933 and 1938 respectively; the former Teutonic Order village of Sontheim also became part of Heilbronn in 1938. The remaining districts followed with the territorial reform in the 1970s: Klingenberg in 1970, Kirchhausen in 1972, Biberach, Frankenbach and Horkheim in 1974. Apart from the districts of Biberach and Kirchhausen, which are relatively far away from the core city and are completely surrounded by agricultural land, Heilbronn and its districts have grown into an almost closed settlement area.

Floor space allocation

According to data from the State Statistical Office, as of 2015.

Nature Conservation

→ Main article: List of nature reserves in Heilbronn

→ Main article: List of landscape conservation areas in Heilbronn

The following nature reserves are located in the city of Heilbronn:

- Altneckar Horkheim: 43.2 ha (of which 30.9 ha in the Heilbronn municipal area); Horkheim district

- Frankenbacher Schotter: 14.4 ha (of which 4.7 ha in the city of Heilbronn); Frankenbach district

- Köpfertal: 32.0 ha; district of Heilbronn

- Impact slope of the Neckar near Lauffen: 2.96 ha; (of which 0.7 ha in the city of Heilbronn); Horkheim district

- Reed sandstone quarry near the Jägerhaus with surrounding area: 29.6 ha; Heilbronn district

Climate

The Neckar valley near Heilbronn is one of the warmest areas in Baden-Württemberg. It has a temperate continental climate with mild winters and warm to hot summers, which favours the extensive viticulture. According to data from the German Weather Service, the average annual temperature in the normal period 1961-1990 was 9.8 °C, the annual precipitation 758.1 mm.

| Monthly average temperatures and precipitation for Heilbronn

Source: DWD data for the normal period 1961-1990 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Spatial planning

Heilbronn and the surrounding area belong to the northern part of the Stuttgart conurbation. The city is the upper centre of the Heilbronn-Franken region and thus one of a total of 14 upper centres designated in the 2002 state development plan of the state of Baden-Württemberg. It also assumes the tasks of the central area for the entire Heilbronn district except for its northeast, which forms the central area of the city of Neckarsulm. In detail, these are the towns and communities of Abstatt, Bad Rappenau, Bad Wimpfen, Beilstein, Brackenheim, Cleebronn, Eberstadt, Ellhofen, Eppingen, Flein, Gemmingen, Güglingen, Ilsfeld, Ittlingen, Kirchardt, Lauffen am Neckar, Lehrensteinsfeld, Leingarten, Löwenstein, Massenbachhausen, Neckarwestheim, Nordheim, Obersulm, Pfaffenhofen an der Zaber, Schwaigern, Siegelsbach, Talheim, Untergruppenbach, Weinsberg, Wüstenrot and Zaberfeld.

Spatially significant measures are developed for the Heilbronn-Franken region by the Heilbronn-Franken Regional Association.

Heilbronn and its neighbouring towns

Transition zone between gypsum keuper and reed sandstone in the former Heilbronn quarry near Jägerhaus

Heilbronn districts (clickable map)

History

→ Main article: History of the city of Heilbronn

Settlement and founding of the town

The oldest human traces in the fertile Neckar floodplains of the Heilbronn Basin date back to the Palaeolithic Age (30,000 BC). In prehistoric times, ancient long-distance routes, which crossed the Neckar there, already met at Heilbronn. In the 1st century AD, the Romans secured their border along the Neckar Limes with forts, including the Heilbronn-Böckingen fort, where eight Roman roads met. After the Romans, the Alamanni ruled the Neckar region from the middle of the 3rd century and were displaced around 500 by the Franks, who settled their eastern provinces with royal courts. The first larger settlement in the area of today's core city probably goes back to such a royal court.

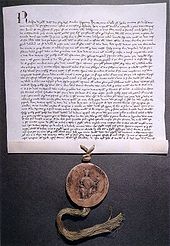

The place is first mentioned as villa Helibrunna in a donation dated to the year 741. The name refers to a well or a spring. A market was first mentioned around 1050, a harbour around 1140. The town developed into an important trading centre early on and passed to their regional princes, the Counts of Calw, after the end of the Carolingians. The former Frankish princely court fragmented into manorial courts, and these in turn broke up into smaller portions. In addition to various counts, monasteries with their Heilbronn manorial courts and the Teutonic Order, which appeared from around 1225 onwards and established the Deutschhof as a commandery and owned the neighbouring town of Sontheim, property rights in Heilbronn also passed into the hands of the patriciate, which became increasingly influential and whose early representatives included the Erer and the Lutwin. In 1225, the city was first designated as an oppidum (fortified city) and was awarded to Württemberg as a fief of the Hohenstaufen King Henry (VII).

In 1281 King Rudolf I of Habsburg granted Heilbronn city rights, whereby a city council was mentioned for the first time, which was formed from the patriciate. Around 1300, St. Kilian's Church was mentioned by name for the first time, as well as a market square with a town hall. With the foundation of the Katharinenspital in 1306, a municipal health and welfare system was established. In 1322 King Ludwig the Bavarian granted the city high jurisdiction.

The port and the water-powered mills on the Neckar, which could be dammed and diverted for the benefit of the city from 1333 onwards thanks to the Neckar privilege, allowed trade to flourish in Heilbronn. Heilbronn became the "Little Venice" of inland navigation due to the transhipment monopoly. In 1360, the citizens of Heilbronn were able to acquire the office of Schultheißen (mayor) from the previous feudal holder, Württemberg.

Imperial city from 1371

On 28 December 1371, the city became an imperial city by a constitution of Emperor Charles IV. An extremely close relationship with the emperor as well as an alliance with the Electoral Palatinate from 1417 to 1622 strengthened the position vis-à-vis Württemberg.

From 1500 Heilbronn as an imperial city belonged to the Swabian Imperial Circle, while the territories of the Teutonic Order, Ballei Franconia, belonged to the Franconian Imperial Circle.

In 1519 Götz von Berlichingen was imprisoned in Heilbronn as a prisoner of the Swabian League. In the Peasants' War Jäcklein Rohrbach appeared as a rebellious peasant leader in Heilbronn. Together with the peasants of the Neckar-Odenwald region, he committed the Weinsberg Bloody Deed around Easter 1525 and subsequently plundered the Heilbronn Carmelite monastery, which was located outside the city walls. In the city itself, the anger of the peasants was directed only against the Teutonic Order in the Deutschhof.

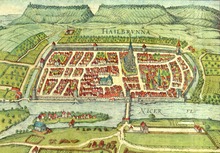

The city of Heilbronn, which had the right of patronage over the preacher's office in the Kilianskirche, joined the Reformation early on. The Heilbronn Catechism of 1528, written by the Kilianskirche preacher Johann Lachmann, is one of the earliest Protestant catechisms. The first Protestant mayor Hans Riesser took part in the Protestation at Speyer in 1529. The economic stability in the further course of the 16th century led to a further flourishing of the city, in which about 4000 people lived at that time. Numerous historic buildings date back to this period, including the ornate west tower of St. Kilian's Church, the Meat House and Heilbronn Town Hall.

During the Thirty Years' War, the town and the surrounding imperial villages suffered greatly. After the Battle of Wimpfen, Neckargartach was burned down in 1622. In 1633, the Swedes concluded the Heilbronn League with the Protestant southern German imperial cities in the Deutschhof. At that time the city was surrounded by a bulwark. From 1634 to 1647 the city was again in the hands of imperial troops, after which French and then Electoral Palatine troops moved in. Even after the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, however, the town remained a deployment point and Protestant district fortress of the Swabian Imperial Circle. In late 1688 Heilbronn was occupied in the Palatinate War of Succession by the French under Ezéchiel de Mélac, who, on their withdrawal from approaching Electoral Saxon troops in December 1688, abducted nine members of the patrician families as hostages, some for over a year. In 1694, the last witch trial took place in the imperial city.

After the political stabilization, magnificent buildings in rococo style were erected around 1750, such as the municipal archive building, the orphans', breeding and workhouse, the Kraichgau archive and the shooting house. From 1770 onwards, Heilbronn became one of the largest south-west German transhipment points for slaughter cattle for over a century due to the cattle and horse market.

Württemberg chief town from 1802 onwards

As a result of the Mediatisation in September 1802, Heilbronn, together with other imperial towns, came to Württemberg and became the seat of the Oberamt Heilbronn. Two of the Oberamtmänner of the 19th century, namely Joseph Christian Schliz and Friedrich Mugler, became the first two honorary citizens of the city.

From 1815, the Neckar was made navigable again, which had been blocked by countless weirs and mills since the High Middle Ages. For this purpose, the Wilhelmskanal was built from 1819 to 1821. Industrialization in Heilbronn was driven by the Heilbronn paper mills on the Neckar, which switched to factory-like production around 1820 with the installation of large paper machines and developed into large operations, which in turn were followed by downstream processing plants. In 1832 Heilbronn was the city with the most factories in the Kingdom of Württemberg, it was called the Swabian Liverpool.

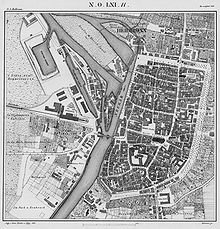

In the course of the 19th century, the population of the town increased about sixfold, so that it rapidly outgrew the medieval town boundaries, which had remained almost unchanged for centuries. The old city gates and walls were demolished. New roads and bridges were built. From 1839 onwards, suburbs were developed according to plan, now also to the west of the Neckar, where the old railway station stood from 1848 onwards. Heilbronn was initially the terminus of the Württemberg Northern Railway from Stuttgart. Until 1880, under the direction of the Württemberg State Railways, additional railway connections were built from Heilbronn to other important southern German cities.

Heilbronn was considered the Württemberg centre of the March Revolution in 1848. Until the summer of 1849, there were frequent riots in the city, which could only be suppressed several times by sending royal military from Stuttgart.

With the steady growth of the city, a new general building plan was drawn up by Reinhard Baumeister in 1873, which was adhered to in further urban development until around 1900. The Kaiserstraße became an important east-west traffic axis. In 1875 the raft harbour was built, followed by the salt harbour in 1886 and the Karlshafen in 1888. On January 16, 1892, Heilbronn became the first city in the world to be supplied with long-distance electricity when it was connected to the power grid of the electricity plant in Lauffen. With the Südbahnhof (southern railway station), an important additional freight transhipment point was built in 1900.

Among the most important companies in Heilbronn at that time were the silverware factory Peter Bruckmann & Söhne, the Heilbronn sugar factory, the Cluss brewery, the Knorr soup factory and the Heilbronn engineering company.

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were numerous workers' and sports clubs and a liberal press landscape in the pronounced industrial and working-class city. The future German President Theodor Heuss was editor-in-chief of the Neckar-Zeitung from 1912 to 1917, which enjoyed national attention at the time. The city was considered a "red stronghold". There were no major revolutionary acts during the November Revolution of 1918/19.

The National Socialist era and the Second World War

The local group of the NSDAP, founded in 1923, was insignificant until the "seizure of power", but then from 1933 onwards, under district leader Richard Drauz, energetically put the local associations and the local press on an equal footing. In 1933 the Wuerttemberg Political Police, which from 1936 operated under the name of "Geheime Staatspolizei - Stapoleitstelle Stuttgart", established a field office in Heilbronn, which observed and persecuted political opponents, Jews and forced labourers until the end of the war.

In 1935, with the canalisation of the Neckar, the major shipping route Heilbronn-Mannheim and the Heilbronn canal port were opened, which, together with the other Heilbronn ports, is still an important transhipment point on the Neckar and one of the ten largest German inland ports. In 1936 the motorway to Stuttgart was completed.

The former town of Böckingen was incorporated into Heilbronn in 1933. In the course of an administrative reform, the previously independent communities of Sontheim and Neckargartach were added to Heilbronn on October 1, 1938, which became a city district and at the same time the seat of the new district of Heilbronn. With 72,000 inhabitants, the city was now the second largest in Württemberg after Stuttgart.

On 10 November 1938, the Heilbronn synagogue was destroyed by arson. In the course of 1939, the traditional Jewish community in Heilbronn was almost completely wiped out.

In September 1944, the SS established the Neckargartach concentration camp in the Neckargartach district, a subcamp of the Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp, where at times more than 1,000 prisoners were rounded up who were exploited by forced labor in the armaments industry and elsewhere throughout the city (July 1944 to April 1945, part of the Neckar camps). It was contemporarily referred to as SS-Arbeitslager Steinbock. 246 of those who perished in the process are buried in the concentration camp cemetery on Böllinger Straße.

During the Second World War, Heilbronn was frequently the target of Anglo-American air raids from December 1940 onwards. The British air raid of December 4, 1944, in which the old town was completely destroyed and over 6,500 people lost their lives, became a catastrophe for the city. When American troops occupied Heilbronn on April 12, 1945, the city had only 46,350 inhabitants.

Second half of the 20th century

After the end of the Second World War in 1945, Heilbronn belonged to the American occupation zone and until 1952 to the state of Württemberg-Baden. In an enormous effort, the completely destroyed city was rebuilt in only a few years. Only a few important individual buildings were rebuilt in their historical form, most of the quarters were covered with contemporary architecture of the 1950s. US troops were permanently stationed in Heilbronn from 1951.

After the federal motorway 6 from Heilbronn to Mannheim with the monumental Neckar valley bridge was opened to traffic in 1968 and the A 81 to Würzburg followed in 1974, the A 6 to Nuremberg in 1979, the regional economy took a strong upswing due to improved traffic development. Numerous large companies settled in newly created industrial and commercial areas along the new traffic arteries and the economic region in its current form came into being.

With the incorporation of Klingenberg in 1970, Heilbronn exceeded 100,000 inhabitants and thus became a large city. In 1972 and 1974 Kirchhausen, Biberach, Frankenbach and Horkheim were added. During the district reform of Baden-Württemberg in 1973, Heilbronn remained a district-free city and the seat of the now enlarged Heilbronn district. The city became the seat of the Regional Association of Franconia, from which today's Regional Association Heilbronn-Franconia emerged.

Fleiner Straße and Sülmerstraße, which formed the city's central north-south axis before the war and were retained as thoroughfares during reconstruction, were converted into pedestrian zones in the 1970s, and traffic was calmed in the surrounding areas. The avenue running parallel to it became the most important inner-city north-south axis in its place, and underpasses and buildings in the contemporary style were built along it, such as the 14-storey shopping centre of 1971, the Wollhauszentrum built in 1974 and the Heilbronn Theatre, which opened in 1982.

In 1977 the USA stationed nuclear-tipped short-range missiles of the type Pershing IA on the Heilbronn Waldheide, which were replaced by Pershing II medium-range missiles within the framework of the NATO double decision 1984-1985. The population was not informed about this, then from July 1984 onwards, due to public pressure, the missiles were a topic in the local council and in the regional press. A missile accident at the site in 1985 aroused public opinion, and there were protest rallies and a blockade of the site. After signing the INF treaties, the US Army withdrew the missiles in 1987 and the last units in 1992. Since then, there have been no military installations in Heilbronn.

From 1998 onwards, the city was connected to the local transport network of the Karlsruhe city railway, for which large areas of Heilbronn's city centre were once again redeveloped until 2005.

21st century

The Heilbronn urban railway was extended in sections to Öhringen by 2005 and now crosses Heilbronn from west to east. In the meantime, another branch of this line branches off to Neckarsulm, which was built from 2011 to 2013. Other major new buildings in the city area in recent years include two Neckar bridges and the two shopping centres Stadtgalerie and Klosterhof. In addition, the North and South Towns have been greened and built on as part of the federal-state funding programme "Social City".

In 2005 and 2006 Heilbronn was Germany's first UNICEF Children's City.

The killing of a policewoman in Heilbronn in the early summer of 2007 caused a great stir and brought the city into the international news. However, the alleged perpetrator, the "Heilbronn Phantom", turned out to be a mere construct due to an investigative error in March 2009. Since 7 November 2011, the crime has been attributed to the right-wing terrorist group National Socialist Underground due to weapons found in Zwickau.

In 2007, the city was awarded the contract for the Federal Horticultural Show 2019. An approximately 40-hectare former industrial site directly north of the main railway station was selected as the event site, which has since been extensively prepared for the horticultural show. Following the Federal Horticultural Show, the new Neckarbogen district is to be built there.

Religions

Confession statistics

According to the 2011 Census, 35.8% of residents were Protestant, 23.1% were Roman Catholic, and 41.1% were non-denominational, belonged to another faith community, or did not specify. The number of Protestants and Catholics has decreased since then. In Heilbronn in December 2020, 26.5% of the total population belonged to the Protestant Church, 20.0% belonged to the Roman Catholic Church, and 53.6% of the population was grouped under Other / No Religion in the statistics.

Protestants

Since the Reformation by Johann Lachmann in 1528, Heilbronn had been an almost purely Protestant city with St. Kilian's Church as its spiritual centre. In 1530, the council and the citizens of Heilbronn declared their unity with the Augsburg Confession, and Mayor Johann Spölin signed the Lutheran Formula of Concord of 1577 on behalf of the Heilbronn city council. Catholics were unwelcome, and Jews were forbidden to settle in Heilbronn. After the transition to Württemberg, the city became the seat of a deanery in 1803, today's church district of Heilbronn. In 1823, a generalate was established, from which today's Heilbronn prelature of the Evangelical Regional Church in Württemberg emerged.

Catholics

The city's Catholic community had its mother church in the Teutonic Order Minster of St. Peter and Paul, built by the Teutonic Order, which was also responsible for the few Catholics in the districts that historically belonged to the city. The districts of Biberach, Kirchhausen and Sontheim are traditionally Catholic, as they once belonged to the Teutonic Order and therefore remained Catholic during the Reformation. Today, the Catholic parishes belong to the Heilbronn Deanery of the Rottenburg-Stuttgart Diocese.

Jews

→ Main article: Jewish community Heilbronn

The existence of Jews in Heilbronn has been documented since 1050, but from 1438 until the beginning of the 19th century they were forbidden to reside or settle there. In the 1860s Jews were given equal legal status with other citizens. In 1877 the Heilbronn synagogue was consecrated, the building was destroyed in the Reichspogromnacht in 1938. The National Socialists almost completely wiped out the Jewish community by 1939. In the 1980s there were only six families of Jewish faith in Heilbronn. After that, the community grew to over 150 members, especially due to the influx from Eastern Europe. In 2006, the new Jewish Center Heilbronn was inaugurated. The Jewish community of Heilbronn is a branch community of the Jewish Religious Community in Württemberg with its headquarters in Stuttgart.

Muslims

Numerous guest workers settled in the city and district of Heilbronn after 1960. The number of registered foreigners rose from about 2500 persons in 1961 to 13,700 in 1974 (12% of the resident population). For the Muslims among these people, the first Islamic places of worship were built, at first provisionally in small premises. Gradually, several mosques were built in the city and district of Heilbronn, which can be found in the city area in Goppeltstraße, Hans-Seyfer-Straße, Salzstraße, Weinsberger Straße and Böckinger Straße, among others. Salafist positions are taught in the Bilal Mosque Heilbronn.

The number of Muslims in the Heilbronn district is estimated at over 10,000. The majority of them are Muslims of Turkish descent, some of whom are represented by a Heilbronn branch of DITIB; there are also Muslims of Bosnian, Kurdish, Arab and German descent.

Other

The New Apostolic Church had congregations in Heilbronn and the surrounding area from 1896, which were initially administered from Frankfurt am Main. In the 1920s they then formed their own Heilbronn District, which on 1 January 1926 became an independent administrative district with 212 congregations in Württemberg and Bavaria; the district's headquarters were located at Lerchenstraße 8 in Heilbronn. After the Second World War, the Heilbronn district became the Stuttgart district until 1953, with its seat there.

Jehovah's Witnesses have been documented in Heilbronn since 1920, their first groups gathered in Heilbronn from the "Ernsten Bibelforschern". During the National Socialist era, the relatively small congregation was hostile and persecuted, and numerous members died in concentration camps. The Jehovah's Witnesses re-established a first Kingdom Hall in Heilbronn in 1953, which was followed by numerous other halls up to the present day.

Other denominations represented in Heilbronn are the Greek Orthodox congregation in the Aukirche, the Syrian Orthodox congregation in the Mor Ephräm church, the Adventist congregation, the congregation of decided Christians, the Evangelical Methodist congregation with the Paulus church, the Free Evangelical congregation Heilbronn, International Christian Fellowship with the ICF Heilbronn, the Free Reformed Baptists as well as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Incorporations

Formerly independent communities or parishes that were incorporated into the city of Heilbronn:

| Year | Locations | Increase in ha | Source |

| June 1, 1933 | Böckingen, city (since 1919) | 1135 | |

| October 1, 1938 | Neckargartach | 1125 | |

| October 1, 1938 | Sontheim | 740 | |

| January 1, 1970 | Klingenberg | 272 | |

| July 1, 1972 | Kirchhausen | 1147 | |

| January 1, 1974 | Biberach | 1058 | |

| April 1, 1974 | Frankenbach | 889 | |

| April 1, 1974 | Horkheim | 486 |

Population development

In the 15th century about 4000 people lived within the city fortifications. In 1840, 11,300 inhabitants were counted, in 1890 Heilbronn had 30,000 inhabitants. By June 1, 1933, this number had doubled to 60,000, partly due to the incorporation of the town of Böckingen (11,593 inhabitants in 1925). Heilbronn lost about 40 percent of its population due to the destruction during the Second World War; from 77,000 inhabitants in 1939, only 47,000 remained in 1945.

By 1956, the population had returned to pre-war levels, and on January 1, 1970, it surpassed 100,000 with the incorporation of Klingenberg, making it a major city. By the 1980s, the city's population was consistently around 112,000. After German reunification in 1989 and the opening of the Eastern European states, the population reached a temporary high of about 122,000 in 1993, after which the population declined again until 2000, mainly due to the return of Yugoslavian civil war refugees. Since then, continuous growth has been recorded again. Heilbronn ranked 59th in the list of large and medium-sized cities in Germany with its population as of 31 December 2007. As of 30 September 2012, the population exceeded 125,129 for the first time. However, at the end of May 2013, when the figures of the 2011 census became known, it became apparent that these population figures, which were based on decades of updating old data, were allegedly too high and Heilbronn instead had 116,059 inhabitants on the cut-off date of 9 May 2011. The City of Heilbronn is taking legal action against this before the Stuttgart Administrative Court.

The following overview shows the population figures according to the respective territorial status. Up to 1833, these are mostly estimates, thereafter census results (¹) or official updates of the respective statistical offices or the city administration itself.

Before 1843, the number of inhabitants was determined according to non-uniform survey methods. From 1843 onwards, the data refer to the "local population", from 1925 onwards to the resident population and since 1987 to the "population at the place of principal residence".

|

|

|

¹ Census result

Among the more than 25,000 foreigners in the city, Turks form the largest ethnic group. Already in 1999, the proportion of foreigners was 20.5 %. This rate was also just reached in 2011. According to the 2011 census, 46.1% of Heilbronn's inhabitants have a migration background. Heilbronn is thus the city with the third highest proportion of migrants in Germany after Offenbach am Main and Pforzheim. In 2016, the proportion of people with a migration background in the total population was 52 %, after this proportion had still been 45 % in 2006. Around 63 % of all children and young people come from migrant families.

The former Heilbronn synagogue around 1900

Commemorative plaque to the murder of a policeman on the Theresienwiese 2007

Heilbronner Allee, construction work for the northern branch of the light rail system, March 2012

Heilbronn 1945

Bond for 1000 Marks of the municipality of Heilbronn dated 10 April 1923

Heilbronn 1858

Town charter 1281

View of the imperial city from 1617

Heilbronn with bulwark (1643)

Search within the encyclopedia