Hebrew language

![]()

This article or section is still missing the following important information:

The article does not address the different pronunciation traditions; see also Discussion:Ashkenazim#Category:Jewish language and Discussion:Hebrew language#different pronunciation traditions. It also contains little supporting evidence.

Help Wikipedia by researching and adding them.

Hebrew (עברית 'Ivrit, ![]() ) belongs to the Canaanite group of Northwest Semitic and thus to the Afro-Asiatic language family, also called the Semitic-Hittite language family.

) belongs to the Canaanite group of Northwest Semitic and thus to the Afro-Asiatic language family, also called the Semitic-Hittite language family.

The basis of all later developmental forms of Hebrew is the language of the sacred scripture of the Jews, the Hebrew Bible, whose source writings emerged in the course of the 1st millennium BC and were continuously edited and expanded and finally codified around the turn of the century. (Ancient) Hebrew is therefore often equated with the term "Biblical Hebrew", even if this is based less on linguistic history than on literary history: ancient Hebrew as the language of most of the Old Testament. In the Bible the language is called שְׂפַת כְּנַעַן sefat kena'an ("language of Canaan", Isa 19:18) or יהודית jehudit ("Jewish, Judean"; Isa 36:11 2Kgs 18:26,28 2Chr 32:18 Neh 13:24). After the destruction of the Jerusalem temple by Nebuchadnezzar II in 586 B.C. and the Babylonian exile that followed, the official language there, Aramaic, came into circulation among the Jews, so that from then on Hebrew was in competition with Aramaic and absorbed many influences from it.

After the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 AD, the center of Jewish life shifted from Judea to Galilee and exile. From about the year 200 Hebrew ceased to be an everyday language. It remained, however, a sacred language, but was never used exclusively for liturgical purposes, but also for writing philosophical, medical, legal and poetic texts, so that the vocabulary of Middle Hebrew could expand over the centuries. There is also evidence that the scattered Jewish communities used Hebrew to communicate with each other.

The renewal of Hebrew with the aim of establishing it as the Jewish national language in Palestine began in the late 19th century on the initiative of Elieser Ben-Jehuda. In 1889 he founded the "Council of the Hebrew Language" in Jerusalem, the forerunner of the Academy for the Hebrew Language, with the aim of reviving the language of the Bible, which had hardly been spoken for about 1700 years. Subsequently, modern Hebrew (often referred to as Ivrit in German) came into being, whose differences from biblical Hebrew in writing and morphology are extremely slight, but in syntax and vocabulary are sometimes serious.

Hebrew script

See Hebrew alphabet and the entries under each letter, from Aleph to Taw. Writing direction from right (top) to left.

Grammar

→ Main article: Ancient Hebrew grammar

For the grammar of modern Hebrew, see Ivrit.

Nouns

Ancient Hebrew, like all Semitic languages, belongs in principle to the case languages. Since the failure of case inflection in the Canaanite group of Semitic languages, however, cases are no longer used to distinguish between subject and object as early as the 10th century BC, but the object can optionally be marked with a special nota objecti, although this is only possible for determinate objects. Inflection, however, plays an important role in the formation and derivation of verbs, nouns, the genitive construction status constructus, which in Hebrew is called Smichut (סְמִיכוּת - "support").

Status Constructus

Examples of the genitive compound (Smichut):

bájit (בַּיִת) = house; lechem (לֶחֶם) = bread; bējt lechem (בֵּית-לֶחֶם) = house of bread (Bethlehem).

In genitive compounds, the definite article is placed before their final constituent:

aliyah (עֲלִיָּה) = repatriation, repatriation; no`ar (, נוֹעַר, נֹעַר) = youth; aliyat ha-no`ar (עֲלִיַּת הַנּוֹעַר) = the return (to Israel) of the youth.

The relationship of possession can be rendered with the help of the classical short form (noun with a pronoun ending) or a longer, paraphrased phrase,

e.g. of: Son = בֵּן ben: my son = בְּנִי bni or הַבֵּן שֶׁלִּי ha-ben scheli.

The latter literally means: the son who is from me. Here a new preposition ("of") has arisen from a relative clause (sche... = der, die, das) and the preposition le-, which is still unknown in biblical Hebrew. At "bni" as well as at "scheli" the pronominal ending of the 1st person singular (my, me, me) is recognizable.

Genera

The Hebrew language has two grammatical genders or genera: masculine and feminine. Female nouns and names usually end with ...a (ה...) or ...t (ת...). Example: Sarah (שָׂרָה), `Ivrith (עִבְרִית). However, there are some exceptions, for example the word "lájla" (לַיְלָה - night) ends with the letter "He" and is still grammatically masculine. Feminine nouns can also have masculine endings. Abstract nouns are usually assigned to the feminine genus.

The stress is mostly on the last syllable, in some cases also on the penultimate syllable, in the case of foreign words also on other syllables (אוּנִיבֶרְסִיטָה univérsita "university"). The stress is (in Modern Hebrew) weakly phonemic, so there are occasionally pairs of words that differ only in stress (בִּירָה birá "capital", בִּירָה bíra "beer"). Some personal names can be stressed in two different ways, giving each a different emotional connotation.

Hebrew nouns and adjectives can be defined with the definite article הַ... "ha". Indefinite nouns or adjectives do not carry an article at all. The definite article is written together with the associated word. Example: נוֹעַר no`ar = youth, הַנּוֹעַר hano`ar = the youth. When the article is prefixed, the following consonant is usually given a dot ("Dagesch forte"), indicating doubling. Before consonants that cannot be doubled, the article receives a long -a ("qametz").

Verbs

Except in Biblical Hebrew, Hebrew verbs have three tenses: past, future and present. Strictly speaking, however, only past and future are true conjugations with 1st, 2nd, and 3rd person forms in the singular and plural, while the present uses the participle. Here, like the Hebrew adjective, each verb has four forms: Masculine singular, Feminine singular, Masculine plural, Feminine plural. The person is indicated by adding the personal pronoun. An example of the formation of the participle:

| כּוֹתֵב אֲנִי-אַתָּה-הוּא (aní, atá, hu) kotév | (I, you, he) [m.] write, write, write (literally: I (m.), you (m.), he a writer) |

| כּוֹתֶבֶת אֲנִי-אַתְּ-הִיא (aní, at, hi) kotévet | (I, you, she) [f.] write, write, write (literally: I (f.), you (f.), she (sg.) a writer) |

| כּוֹתְבִים אֲנַחְנוּ-אַתֶּם-הֵם (anáchnu, atém, hem) kotvím | (we, you, they) [m.] write, write, write (literally: we (m.), you (m.), they (m. pl.) writing) |

| כּוֹתְבוֹת אֲנַחְנוּ-אַתֶּן-הֵן (anáchnu, atén, hen) kotvót | (we, you, they) [f.] write, write, write (literally: we (f.), you (f.), they (f. pl.) writing) |

serves the line break, please do not remove

In ancient Hebrew, a clear distinction between "present", "past" and "future" is not possible. With the finite verb, two types of action are distinguished, distributed between two conjugations, traditionally called "perfect" and "imperfect":

- Perfect tense = completed, stating action (in post-biblical Hebrew: past tense)

- Imperfect = unfinished, pending action (in post-biblical Hebrew: future).

Moreover, there are two derivations of these conjugations in Biblical Hebrew which reverse their sense:

- Imperfectum Consecutivum = completed, ascertainable action

- Perfectum Consecutivum = unfinished, outstanding act.

The respective consecutivum form differs from the normal form of the perfect or imperfect in that it is preceded by the copula "and". In the case of the Imperfectum Consecutivum, the following consonant is also doubled (Hebrew מְדֻגָּשׁ, m'duggash), and the stress often shifts to the penultimate syllable. In Imperfectum Consecutivum, perfective forms stressed on the penultimate syllable are final stressed. Because of the preceding "and", consecutivum forms can only ever be placed at the beginning of the sentence or half-sentence; no other part of the sentence, not even a negation, may precede them.

Modern grammars have abandoned the traditional designations "perfect" and "imperfect", since these attempt to describe the action type in terms of content, which fails because of the respective Consecutivum variant. The perfectum consecutivum precisely does not describe a "perfect", completed action, but on the contrary an "imperfect", unfinished one. So the term "perfect" is inaccurate. The same applies analogously to "imperfect". The new terms no longer describe the content, but only the external form: The perfect is now called afformative-conjugation (abbreviated: AK) and the imperfect preformative-conjugation (PK). AK indicates that all forms of this conjugation (except one) have an ending, that is, an affix or afformative (sg.: kataw-ti, kataw-ta, kataw-t, kataw, katew-a; pl.: kataw-nu, ketaw-tem, ketaw-ten, katew-u); PK indicates the prefix or preformative, the prefix, which all forms of this conjugation receive (sg.: e-chtow, ti-chtow, ti-chtew-i, ji-chtow, ti-chtow; pl.: ni-chtow, ti-chtew-u, ti-chtow-na, ji-chtew-u, ti-chtow-na). The Consecutivum forms are called AK or PK with Waw conversivum, i.e. reversing Waw. The letter Waw stands for the copula "and", which is written with this letter in Hebrew. PK with Waw conversivum (Imperfectum Consecutivum) is the typical narrative tense of the biblical texts and is therefore also called Narrativ.

The function of the waw conversivum is attested only for Biblical Hebrew and finds no equivalent in other Semitic languages, such as Arabic or Aramaic.

The basis for deriving all conjugation forms is the "root" (root of the word), which is composed of the consonants that occur in all or most forms of the verb and its derivatives. In the case of the Hebrew verb for "to write," these are כָּתַב, i.e., "k-t-w." Depending on which form is to be formed, the vowels typical of the form are interposed; in many forms, moreover, prefixes and/or suffixes typical of conjugation are added (cf. the forms of the participle and of AK and PK listed above). Accordingly, conjugation in Hebrew, as in all Semitic languages, takes place before, in and after the usually purely consonantal root; most roots consist of three consonants.

Besides AK, PK and participle, Hebrew knows infinitive and imperative forms. The antecedent and future II, on the other hand, are unknown. There are also almost no specific modal forms (subjunctive); they are almost always identical with PK (or derived from it by slight modification).

Unlike, for example, Latin or German verb stems, Hebrew roots can be conjugated according to several patterns, e.g. as "intensive stem" or "causative". Thus, apart from the conjugations designated as AK and PK, which denote action type or tense, there are additional conjugations, each of which forms its own AK and PK, as well as infinitives and imperatives. By these additional conjugations (intensive stem, causative) the basic meaning of the root is varied; they are the most important instrument in the formation of new words and are exceedingly productive. Below are three examples of infinitives of the root "k-t-w" in different conjugations:

- לִכְתּוֹב lichtów: to write (basic meaning).

- לְהִתְכַּתֵּב lëhitkatéw: "to write to each other", i.e. to correspond (intensive stem).

- לְהַכְתִּיב lëhachtíw: "to give to write", i.e. dictate, prescribe (causative).

Moreover, the conjugations are the basis of many noun formations, such as:

- מִכְתָּב michtáw: letter

- הַכְתָּבָה hachtawá: Dictation.

- הִתְכַּתְּבוּת hitkatwút: correspondence

(The change from k to ch in some of the forms mentioned is a common phonetic shift in Hebrew and occurs in the inflection of many words; the same letter is written in the Hebrew script).

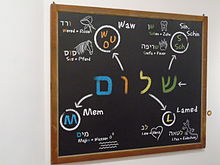

Tablet with the word שלום or shalom (peace).

Questions and Answers

Q: What language is Hebrew?

A: Hebrew is a Semitic language.

Q: When was it first spoken?

A: It was first spoken in Israel.

Q: Who speaks Hebrew?

A: Many Jewish people also speak Hebrew, as Hebrew is part of Judaism.

Q: How long has it been used for?

A: It was spoken by Israelites a long time ago, during the time of the Bible.

Q: Why did Jews stop speaking Hebrew?

A: After Judah was conquered by Babylonia, the Jews were taken captive (prisoner) to Babylon and started speaking Aramaic. Hebrew was no longer used much in daily life, but it was still known by Jews who studied halakha.

Q: How did Modern Hebrew come about?

A: In the 20th century, many Jews decided to make Hebrew into a spoken language again. It became the language of the new country of Israel in 1948. People in Israel came from many places and decided to learn Hebrew, the language of their common ancestors, so that they could all speak one language. However, Modern Hebrew is quite different from Biblical Hebrew, with a simpler grammar and many loanwords from other languages, especially English. As of 2021, Hebrew has been the only dead language that had been made into a living language again.

Q: What language was The Bible originally written in?

A: The Hebrew Bible was originally written in Biblical Hebrew

Search within the encyclopedia