Hakka people

![]()

This article is about the Hakka ethnic group. For the Hakka language, see Hakka (language).

The Hakka (Chinese 客家, pinyin Kèjiā, Hakka Hag-gá, Jyutping Haak3gaa1 - "guest family") are one of the eight Han Chinese ethnic groups. They have their own form of the Chinese language, Hakka, which is divided into several sub-dialects, and have certain cultural characteristics.

In the 21st century, the Hakka live in other countries in Asia and overseas in addition to China. They have spread in several migratory movements in southern China and from there further in Taiwan, Southeast Asia, North and Central America and Australia. According to Japanese researcher Hideo Matsumoto, they originally came from the area around Lake Baikal in Siberia. The native population is called "Bunti(ngin)" (本地(人), běndì(rén) - "ancestral land(people)").

The name Hakka means 'guests' (客家人, Kèjiārén). There are over 60 million Hakka worldwide, some of whom are now unable to speak Hakka. On the other hand, there is a strongly grown and in some places quite influential movement that sustainably promotes Hakka cultural heritage with Hakka culture-specific educational programs and defends the cultural location of the Hakka in the Chinese world.

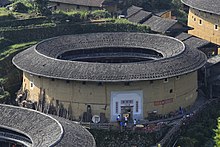

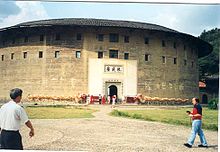

The round buildings (圓樓 / 圆楼, Yuánlóu) of the Hakka in Yongding County of the district-free city of Longyan in Fujian Province are particularly well known. However, they also exist in square form (方樓 / 方楼, Fānglóu). They are made of rammed mud walls and were mainly used for protection from enemies.

Hakka settlement (Tulou)

The migration history of the Hakka

Ethnicity and background of Hakka research in German-speaking countries

The term "Hakka" refers to one of the eight Han ethnic groups, which are distinguished from the other Chinese ethnic groups by their own culture, language and history.

This ethnic group with its peculiarity became known in the German-speaking world for the first time through Basel missionaries. After the collapse of Karl Friederich Gützlaff's "Chinese Association" in Hong Kong, these had taken over the care of his assistants and, under Praeses Rudolf Lechler, the reorientation of the work after 1858. The management of the work and the missionary work among the Hakka was in the hands of the founder of the Hakka mission Hamberg since 1852. The Basel Mission published a small German-Hakka dictionary and a booklet on Hakka grammar.

Other differences between the Hakka and other Han groups are also found in their religious beliefs, the status of women, and the importance of good education for both sexes. The Hakka women grew their feet naturally and did not have lotus feet through centuries of tradition. Religious beliefs traditionally focus on dealing with the yin-yang concept of Taoism, controlling and balancing the two poles of force under the guidance of the geomancer or Taoist priest, and high respect for ancestors. They do not, traditionally unlike the rest of the Han Chinese, worship a large pantheon of gods. The Hakka trace their ethnic origins to the Central Asian Huns. For centuries, the Huns (Xiongnu) were considered the arch-enemies of the Chinese.

Genetic research and ethnic developments

When the first emperor of China unified the Chinese kingdoms in 221 BC, the Hakka living in them became culturally isolated. As a result of this separation, they developed their language and culture in the Han Chinese environment. As a result, they became one of the main tribes of today's Han Chinese.

Hideo Matsumoto believes the Hakka are more related to the Japanese and Koreans than to the Chinese because of genetic similarities, and invested many years of his research to carefully prove genetic similarities of Hakka with Japanese and Koreans. His research results show the common genetic origin of the Japanese, Koreans and Hakka, and have an almost identical genetic structure with the Buryats and Yakuts of Lake Baikal in Siberia. From this, Hideo Matsumoto concludes that the Hakka must have originally come from the Central Asian Baikal region in the Altai, where he assumes they migrated between 12000 and 3000 BC.

The Hakka settled in China, later in Taiwan, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Cambodia, Singapore, Hong Kong, Hainan, Indonesia, Hawaii, Suriname, East Timor, and more recently in Australia. With each wave of emigration, a little more of the Hakka's Central Asian cultural heritage was lost. Emigration of the Hakka from imperial China occurred in five major waves beginning in the 7th century AD. Therefore, in Taiwan, for example, which is home to more than 4.6 million Hakka (18.7% of Taiwan's population in 2008), there are highly diverse local traditions among the Hakka. Waves of emigration have often been accompanied by natural disasters, as well as epidemics of famine and disease. As "immigrants" (客家人, in Mandarin the name Hakka means 'guests') they were the first to make room and move out.

The five major phases of emigration

- Phase: In the Qin dynasty from 249 to 209 BC.

- Phase: In the Han Dynasty 307-419 AD (natural disasters, there was a prolonged drought in northern China). In 298 AD, hundreds of thousands migrated from the north via Gansu and Shaanxi to Sichuan and Henan. In 306, over 300,000 Hakka left Shaanxi and established new settlements in the south. As early as the mid-5th century, the Hakka formed large colonies in the southern Chinese provinces of Fujian and especially Guangdong. In Anhui province, the Hakka settled until the 7th century.

- Phase: 907-1280 A.D. During these years, continuously larger groups of Hakka advanced further south and populated the mountainous outskirts there as well. The nevertheless soon occurring overpopulation led to a further push of emigrants.

- Phase: Yuan and Ming Dynasties (1241-1644): During these years, some Hakka advanced to the headwaters of the Yangtze River, where they repeatedly came into conflict with Thai, Miao, Yao and Tibeto-Burmese peoples. Beginning in 1670, many Hakka accepted an invitation from the Qing (Manchu) government to settle deserted coastal areas of Fujian and Guandong. During this wave of emigration, a large number of the Hakka left the mainland and migrated to Hainan and Taiwan. In 1865-69, the Dutch Trading Company brought about 2000 Hakka to Suriname in seven shiploads, initiating the fifth wave of emigration.

- Phase: From the year 1867 (time of the Taiping Rebellion): After the collapse of the Taiping Rebellion, masses of Hakka again set out, this time further abroad. Many reached the Americas for the first time in this wave of emigration, while others remained in Southeast Asia, arriving in Singapore and East Malaysia. By 1860, one in four of California's immigrant Chinese miners was a Hakka; by 1878, most of Hawaii's Hakka were from Hong Kong. In Kalimantan a Hakka state was founded, which existed as the Republic of Lanfang from 1777 to 1884.

The above classification of emigration phases was proposed by Clyde Y. Kiang in his book The Hakka Odyssey & Their Taiwan Homeland Elgin(PA), Allegheny Press 1992.

One of the well houses of Yongding, Fujian

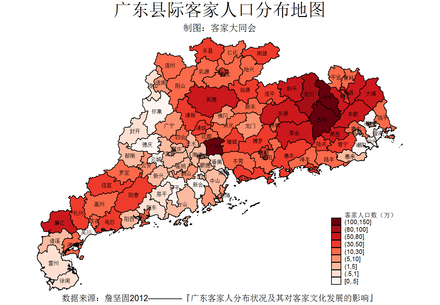

The Hakka of the Chinese province Guangdong

Although many Hakka have emigrated, the highest concentration of Hakka still live in the Chinese province of Guangdong. According to Chung Yoon Ngan, there are more Hakka living in Guangdong than there are Hakka anywhere else in the world.

The immigration of the Hakka to the areas mentioned below began in the Song Dynasty (960 to 1279 AD).

After the Song Dynasty was replaced by the Mongols, the Hakka in Guangdong dispersed to various regions of the province and on to Fujian. Especially in the areas of Meixian, Dongguan, Huizhou, Dabu, Haifeng, Lufeng, Yongding, Yongxin as well as in other mountainous regions, they built villages and lived their customs in isolation. Hakka traditionally served as the vernacular. There was a strong growth and spread of their culture.

In the east of Ling Nan

- Mei Xian (梅縣)

- Jiao Ling (蕉嶺)

- Ping Yuan (平遠)

- Xing Ning (興寧)

- Wu Hua (五華)

- Feng Shun (豐順)

- Da Pu (大埔)

- Rao Ping (饒平)

At the lower reaches of the Dong Jiang

- Lian Ping (連平)

- He Ping (和平)

- Xin Feng (新豐)

- Long Men (龍門)

- Long Chuan (龍川)

- He Yuan (河源)

- Zi Jin (紫金)

- Hui Yang (惠陽)

- Bo Luo (博羅)

- Dong Guan (東莞), Bao An (寶安)

To the north the course of the river along the Bei Jiang

- Cong Hua (從化)

- Hua Xian (花縣)

- Qing Yuan (清遠)

- Ying De (英德).

- Weng Yuan (翁源)

- Qu Jiang (曲江)

- Yue Chang (樂昌)

- Ru Yuan (乳源)

- Shi Xing (始興)

- Nan Xiong (南雄)

- Lian Xian (連縣)

- Lian Shan (連山)

To the west, along the Xi Jiang

- He Shan (鶴山)

- De Qing (德慶)

- Yun Fu (雲浮)

- Si Hui (四會)

- Si Chuan (寺川)

In the southern plains of Guangdong

- Chi Xi (赤溪)

- Fang Cheng (防城)

- He Pu (合浦)

- Qin Xian (欽縣)

In the eastern coastal regions of Guangdong

- Hai Feng (海豐)

- Lu Feng (陸豐)

Share of Hakka population in Guangdong (2012)

Search within the encyclopedia