Hagia Sophia

![]()

This article describes the best known of all Sophienkirche churches. For other churches of this name, see Sophienkirche.

Hagia Sophia (from Greek Ἁγία Σοφία "holy wisdom"; Turkish Ayasofya) or St. Sophia's Church is a former Byzantine church built from 532 to 537 AD. This was used as a mosque from 1453 to 1935 - and has been again since 2020. From 1935 to 2020 it served as a museum (Ayasofya Müzesi, "Hagia Sophia Museum").

Hagia Sophia is located in Eminönü, a district in the European part of Istanbul. After the burning down of two predecessor buildings, Emperor Justinian pursued a particularly ambitious building policy program with the construction of a domed basilica in the 6th century AD. In this context, it is not only the last of the great churches of late antiquity to be built in the Roman Empire since Constantine the Great, but in its architectural uniqueness it is often regarded as a church without precedent or imitation. The dome of Hagia Sophia, with an original span of 33 meters, remains to this day the largest brick dome built over only four supporting points in architectural history. With its gigantic implementation and the proportions and special harmony of its interior, it is considered one of the most important buildings of all time. Due to its special structure and the novel idea of the interpenetration of the central space and the longitudinal basilica, which was realized here for the first time by Isidore of Miletus and Anthemios of Tralleis, a building was created that explored the limits of the available technical possibilities of late antiquity. It is one of the most audacious man-made constructions and one of the most important buildings of the last 1500 years.

As the last great and by far the most important building of early Byzantine architecture and art of late antiquity, it is seen in its function as a central place of Byzantine representation of power as an embodiment of the Byzantine idea of empire and is thus one of the important key works for understanding the cultural-historical phenomenon of Byzantium. At the same time, it gave rise to a new paradigm of church building, partly in contrast to its older predecessors, which would subsequently form one of the cornerstones of Christian architecture, having a lasting influence on sacred architecture in both East and West. Hagia Sophia was built not least as an expression and demonstration of Justinian's imperial power; by manifesting the uniqueness of its commissioner and the display of his preeminent position, the structure also depicts Justinian's claim to God's grace in earthly rule over the Christian world. Hagia Sophia was the cathedral of Constantinople, the main church of the Byzantine Empire as well as the religious center of Orthodoxy, and is now a landmark of Istanbul. Its architectural conditions were a central factor in the development of the late ancient liturgy and liturgical music celebrated in it.

As the coronation church of the Byzantine emperors (since 641), the cathedral of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and the site of important historical events, Hagia Sophia is connected in a special way with Byzantine history and, more generally, as the universally conceived model church of the capital of the Christian oikumene, Constantinople, with the history of ideas of Christianity in Turkey. Planned as a building of universal importance, it also remained a universal Christian spiritual center throughout the Middle Ages. On the right side of the Naos, the Omphalion therefore also symbolizes the center of the earth, the proverbial "navel of the world". However, its construction and symbolic power were of extraordinary importance, especially for Orthodox Christianity and the Empire. Therefore, it is still considered a great sanctuary by most Orthodox Christians.

After the Ottomans conquered Constantinople in 1453, Christian insignia, interior furnishings, decorations and bells of Hagia Sophia were removed or covered by plaster. Subsequently adapted as the main mosque of the Ottomans, it had a great influence on the development of Ottoman architecture. The Ottoman sultans of the 16th and 17th centuries based the mosques in the great imperial külliyas on the structural model of Hagia Sophia. Main works were created here by Sinan. In general, among the important early Christian sacred buildings, Hagia Sophia has survived less modified today than the great early Christian basilicas of Rome and Jerusalem, despite the Islamic indenture from a purely architectural perspective.

At the suggestion of Atatürk, Turkey's first president, the Council of Ministers decided on November 24, 1934, to convert the mosque into a museum. On July 10, 2020, Turkey's Supreme Administrative Court ruled that Hagia Sophia may be used as a mosque again in the future. By order of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the first Islamic prayer was set for July 24, 2020.

Building historical classification

Hagia Sophia is one of the most outstanding buildings of late antiquity and the most important example of the dome basilica building type. The dome basilica combines building elements with a longer history. These include the basilicas that were already built in the Roman Republican period as places of assembly, market and jurisdiction, as well as the domed buildings of Roman mausoleums, as they were built in the Imperial period.

The most striking element of Hagia Sophia is the monumental dome that dominates the entire interior. It rests on pendentives between four massive pillars. In the north and south of the rectangular central building, the lateral thrust is absorbed by buttresses above the side aisles. In the west and east, this task is performed by conches with half-domes, whose abutments in turn are located in a total of four smaller domes. Above the narthex is the imperial tribune and on each side a gallery for the women (gynaikeion). The architectural significance of the dome lies not in its size, since it was already possible for the Romans to erect even more extensive domes in the first century AD, but in the fact that for the first time it rests on only four pillars and thus floats, as it were, above the space below. The attempt to increase the architectural challenge with an extremely flat dome failed due to repeated violent earthquakes.

The church, dedicated to divine wisdom, stands on a rectangle about 80 m long and 70 m wide. The span of the dome is about 32 m; the dome space is 55 m high from the floor to the apex of the dome.

Interlocking geometries conceal the enormous support system that carries the huge dome. This is hidden behind elegantly arranged galleries that give the structure the illusion of dematerialization of its vertical wall surfaces.

Today's structure and equipment

At the suggestion of Atatürk, Turkey's first president, the Council of Ministers decided on November 24, 1934, to turn the mosque into a museum. Subsequently, the history of the building became more and more visible and its continuous use as a religious site became clear. In today's presentation, the last caesura in the history of architecture and art at Hagia Sophia in 1453 is embedded in the context of its entire history. Directors of the museum, such as Feridun Dirimtekin (1955 to 1971), have contributed significantly to this development. In the effort to make the original church space largely tangible again, care was nevertheless taken not to destroy the later Muslim installations, although compromises had to be made on some points due to protests from the population.

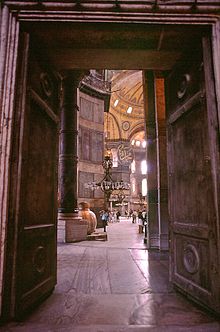

Porches

In front of the entrance to the church, some foundations of the fifth-century building and the bell tower of the Latin Empire (13th century) can still be seen. The base of the building forms a rectangle of about 70 m × 75 m. The church had two porches in the west, the so-called narthex, as well as the outer exonarthex. In the latter, some non-figurative mosaics from Justinian times are still preserved. Five gates - in the meantime all but one walled up - led from the atrium into this hall, five more from here into the narthex. Above the middle of the gates, one finds a tenth-century mosaic showing the emperors Constantine and Justinian offering a city (Constantinople) and a church (the Hagia Sophia) to the enthroned Mary with the Christ Child. The most impressive mosaic of the narthex shows Christ Enthroned above the Emperor's Gate, the middle of the nine entrances into the nave. This was reserved for the ruler alone, and its door frame is made of bronze.

Naos

The main room or naos (Greek ναός "temple") is dominated by the dome, which is 31 meters in diameter and 56 meters high, with a floor area of 755 m². In addition, there are smaller semi-domes and other shell-shaped domes in the west and east. Six-winged angels are depicted in the pendentifs. The main dome, the semi-domes, the vaults of the narthex, the side aisles and the galleries - a total area of more than 10,000 m² - were originally covered with gold-primed mosaics. Rare marble inlays from all parts of the Roman Empire were used for the magnificent ancient facings of the columns and walls.

The apse has mosaics from the ninth century: an enthroned Mother of God with Child, to the right of it the Archangel Gabriel, to the left Michael, its stained glass windows are an ingredient of the 19th century and were made during the restoration works in 1847-1849. In the south of the main hall today there is also the Muslim prayer niche called Mihrab, in the central nave to the right in front of the apse the minbar - a kind of pulpit -, to the left the sultan's box from the 18th century.

Emporiums

On the galleries, which were reserved for women by the Byzantines as well as the Turks, there are still remains of the old mosaic: On the north gallery the image of Emperor Alexander (912-913), on the south gallery a mosaic with Empress Zoe and her husband Constantine IX, next to it a mosaic of Emperor John II Komnenos with Empress Irene and her son Alexios offering gifts to the Mother of God and Child. The most splendid mosaic is a devotional image, a Deesis, from the 14th century, showing Jesus with Mary and John the Baptist. The lower part with the once probably donor figures has been destroyed, but the faces have been preserved. On the top of the parapet there are graffiti from various centuries, including one in runic script from the 9th century with the name of a Viking, Halfdan, who probably belonged to the emperor's bodyguard.

From the gallery, one has a good view of the 7.5-meter-diameter wooden round shields attached to the main pillars. On them are inscribed in Arabic calligraphy the names of Allah, the Prophet Muhammad, the four "rightly guided" caliphs Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ali, and the names of the Prophet's two grandsons Hassan and Hussein. The shields were designed by the calligraphy artist Kazasker Mustafa İzzed Effendi (1801-1877) between 1847 and 1849, when the Swiss architects Gaspare and Giuseppe Fossati were commissioned to carry out the first restoration of Abdülmecid I's building, which was accompanied by architectural studies. The oversized shields replaced eight rectangular panels at that time and are probably due to a special request of the reigning Sultan Abdülmecid I. After the Hagia Sophia was converted into a museum, many unhistoric ingredients, including the shields, were removed. However, due to protests from the imams, they were reinstalled.

Minarets

The Hagia Sophia received four minarets very early. The fluted minaret was built by Sultan Bayezıd II. (1481-1512) built the fluted minaret. In 1573, under Sultan Selim II, the two oldest minarets were demolished and replaced by successor buildings.

Courtyard

Numerous archaeological finds are on display in the courtyard, as well as a Şadırvan (mosque fountain) and five rulers' tombs, known as turbs, where sultans, princes, princesses and sultans' wives were buried: Selim II, Murad III, Mehmed III, Mustafa I and İbrahim.

View from one of the side aisles into the northwest conch of the main nave

The Islamic whitewashing of the four seraphs in the pendentifs was reversed in an exemplary manner on the occasion of Istanbul's designation as Capital of Culture 2010

The Mihrab, the Muslim prayer niche

Interior with the name plates Mohammed, Allah and Abu Bakr

Müezzin Mahfili, the pedestal of the muezzin in the Hagia Sophia; in front of it the omphalion

Carved runic inscription from the 9th century with the name Halfdan on a railing of the south gallery

Baptismal piscina of Hagia Sophia, probably the largest in Christendom

Meaning

Building historical classification

The Hagia Sophia is the most important example of a late antique domed basilica and outshone older church buildings in the eastern Mediterranean region, transcending cultures. The dome basilica as well as the type of the cross-domed church, which developed almost at the same time, are the last common Christian building forms, which connect the western and eastern church architecture. After the conquest of Constantinople, Islam also adapted the Christian dome basilica in many countries, continuing the Byzantine legacy. Since its construction, Hagia Sophia has therefore been an epoch-making building and work of art, which has been received by architects right up to the present day because of its overall conception. Many experts focus their gaze on the free-floating dome, nearly 56 meters high and 31 meters in diameter, which rests on only four pillars and is particularly impressive because of its shallow angle of inclination. After the serious loss of constructional knowledge since late antiquity, the enormous Roman representational buildings became incomprehensible feats of wonder for future generations. It is only since the 20th century that these achievements can be reconstructed with modern materials. Eugène Michel Antoniadi was one of the first to scientifically study the building and its dome, publishing a three-volume work on Hagia Sophia in 1907. In 2000, it was added to the List of International Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks by the American Society of Civil Engineers. Since 2002, the Gesellschaft für Geophysikalische Untersuchungen in Karlsruhe has been investigating the current condition of the building (statics and construction) with the help of radar technology (2006). On the basis of the data collected in this way, proposals are to be made for securing the dome in particular. Today, the Hagia Sophia is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Sacral building

While the Orthodox Church made Hagia Sophia the basis and synonym for perfect Byzantine church building, an adoption of Byzantine building schemes in the interpretation of sacred spaces also took place in important Catholic sacred buildings, the most important representatives of which are Charlemagne's Palatine Chapel in Aachen and St. Mark's Church in Venice. After the capture of Constantinople in 1453 by the Ottomans, the most remarkable sustained reception of art occurred, since the conquerors were representatives of a completely different artistic and cultural sphere, who at the same time brought with them a new religion. In the aftermath of the Ottoman conquest, the model of the domed central building became exemplary for Ottoman mosque construction, such as in the Suleymaniye Mosque, replacing the longitudinal rectangular pillared hall that had become the model since the Umayyad Mosque.

Reception

Sacral building

Orthodox sacral buildings

The Hagia Eirene in Constantinople, also destroyed during the Nika revolt in 532, was rebuilt in parallel with the Hagia Sophia and also designed as a domed basilica. After that, only a few examples of true domed basilicas can be found. Although the cube-shaped building with a dome over cruciform vaults prevailed in Byzantine construction as a symbolic cosmos of the Christian universe, the technical difficulties and high construction costs of erecting large domes largely reduced the dimensions in the Byzantine area and solidified them into a fixed canon from the 9th century onward as cross-domed churches, appearing in various variations.

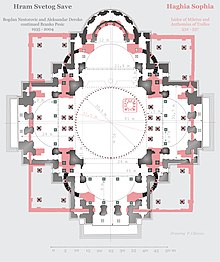

The most ambitious contemporary building, inspired by Hagia Sophia, is the Cathedral of St. Sava in Belgrade, construction of which began in 1935 on Vračar Hill, the presumed site of the cremation of the relics of St. Sava of Serbia. It was consecrated in 2004; the works are not yet completed.

In place of the former St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church destroyed at Ground Zero in New York, a successor building designed by Swiss-Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava is being built on architectural models of Byzantine architecture, in particular the Hagia Sophia, the Chora Church and the Rotunda in Thessaloniki, as the St. Nicholas National Shrine, the foundations of which were consecrated at the 9/11 Memorial on October 14, 2014. Calatrava said during the dedication of the building foundations that Hagia Sophia represents the paradigm of Orthodox architecture. Similarly as the Parthenon is for him the paradigm of classical ancient architecture, Hagia Sophia is for him also the "Parthenon of Orthodoxy". The neo-Byzantine domed church of Saint Nicholas will thus quote the 40 windows of the dome of Hagia Sophia through 40 ribs of the dome in Saint Nicholas, and the mosaics of Hagia Sophia also became an important inspiration of Calatravas for the design of the church. The highly symbolic structure is the only non-secular structure that will be built on the site of the 9/11 memorial in Liberty Park. The exterior facade of white American marble will be lit from within, thus and its position above the "World Center Memorial Oaks" will not only give it a prominent visual axis, but also position it as a spiritual vertical within the memorial ensemble as a place of worship for visitors of all faiths. Calatravas' watercolor sketches and studies of Saint Nicholas were exhibited at the Benaki Museum in Athens in 2015. In an interview with the BBC, Calatrava explained that the idea for the church's design came directly from the mosaic of Hagia Sophia in the Founder's Fresco, as well as the Mother of God in the south gallery of Hagia Sophia. In a visual analogy between the model of Hagia Sophia and the enthroned Mary with Jesus, he developed the silhouette of the church.

Muslim sacred buildings

The building served as a mosque from May 29, 1453 until 1931, when it was secularized and opened as a museum on February 1, 1935.

The adaptation of authoritative Christian architectural forms has a long tradition in Islam. The military expansion of Islam began shortly after Mohammed's death. After the conquest of Syria in 636, the conquerors appropriated many Christian basilicas and copied their architectural forms. The most famous example is the Umayyad mosque in Damascus. After the fall of Constantinople, an Islamic reception of the Hagia Sophia took place that continues to this day. In the 16th century, Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent attempted to tie in with the imperial sacral building forms of Emperor Justinian with particularly imposing mosques, which were also designed as domed central buildings. Thus, in Constantinople (the city did not receive its official name Istanbul until 1930), the first prototype of this new Islamic building style was the Beyazid II Mosque (1501-1506). Other Ottoman mosques, the most significant of which were built in the 16th and 17th centuries, followed. Most directly indebted to the Haghia Sophia is the Kılıç Ali Pasha Mosque, which has much more of a church than a mosque. After Sinan's buildings of Mihrimah Mosque, Sokullu Mehmet Pasha Mosque or Selimiye Mosque, which as prayer halls strictly embody the central building idea of Ottoman religious architecture, the modification in the design of Kılıç Ali Pasha Mosque is explained in the origin of the client Kılıç Ali Pasha, who was a southern Italian convert to Islam.

Thus, today's most common type of mosque as a central dome building ultimately goes back to the Hagia Sophia, while in the first centuries of Islamic history the type of pillared hall mosque (such as the former main mosque of Córdoba or the Umayyad Mosque) still dominated, the latter originally built as a basilica and only later converted into a mosque.

Catholic sacred buildings

The Saint-Esprit church in Paris, built by Paul Tournon between 1928 and 1935, has a dome-crowned interior completely modeled on the Hagia Sophia. The church, with its 22-meter diameter dome and interiors designed by leading artists of the first half of the 20th century, is one of the most important sacred buildings of the period between the world wars. The dome, made of prestressed concrete, was a special challenge for that time.

Legends and legends

Like other famous historical buildings, Hagia Sophia is the subject of numerous legends and myths. Since the sacred building is of great importance and symbolism for both Christianity and Islam, there are many traditions on both sides. These folk tales are deeply rooted in folklore and faith and are identity-forming.

Orthodox Christianity

A Greek legend, which is still told today, says that the Patriarch, who was celebrating the Holy Liturgy at the time of the Ottoman invasion of Hagia Sophia, disappeared with all the liturgical equipment into a wall of the church, or, in another variant of the legend, he fled through a side door. From there he would return when Hagia Sophia was a church again and finish reading the Divine Liturgy. Another legend refers to the massacre of the citizens who had sought refuge in Hagia Sophia when the Ottomans invaded the city. According to popular belief, only two monks survived the massacre or captivity. They had ascended into the gallery and disappeared into the wall, from which they will return when the city is once again Christian.

According to a well-known tradition, on one of the last days before the conquest, the city was covered by a dense fog that refused to lift. When the fog lifted toward evening, Hagia Sophia was said to be enveloped by a reddish light that rose from its dome to the cross. This was interpreted by the people as a sign that Christianity would soon be bathed in blood. In some variations it is said that that reddish light disappeared above the cross. The most common interpretation of this is that the Holy Spirit left the basilica before it was desecrated. Scientists suspect that it was an effect that can occur after a volcanic eruption.

Islam

After the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans, a legend arose among the new Muslim inhabitants, which had as its true core the problematic construction of the dome of Hagia Sophia due to earthquakes. This tale has been handed down orally in several variants. The central point is the attempt to link the success of the dome construction to the Islamic religious founder Mohammed. The builders are told - more or less spectacularly, depending on the version of the story - that only the prophet of the Muslims, Mohammed, who lives in Arabia, can complete such a dome through miraculous power. Therefore, envoys are sent out to find Muhammad. Only sand blessed by Mohammed, or Meccan earth and water, could bring the dome to fruition. In some variants, Mohammed then prophesies to his followers that he does not want to help the Christians, but sees the Hagia Sophia as a future Islamic place of prayer. One Islamic legend claims that Hagia Sophia stands on a site that the Israelite King Solomon predicted in a prayer. Since Islam sees itself as the only true fulfiller of Judeo-Christian monotheism, the alleged Jewish prophecy in this legend becomes an indication for Muslims to consider the site of Hagia Sophia as destined for them.

Conversion back to an active sacred building

Orthodox Church

The rhetoric between Moscow and Ankara has been very tense for many years. Against the backdrop of the shooting down of a Sukhoi Su-24 of the Russian Air Force by the Turkish army in the Syrian-Turkish border area in 2015, the already poor relations reached their lowest point so far. As a sign of goodwill or "a friendly step," Russian Duma deputies, including Sergei Gavrilov, head of the Property Issues Committee and coordinator of the parliamentary group for the protection of Christian values in the Duma, are calling for the return of Hagia Sophia to the Orthodox Church. It was built as such, and it had been used as a church much longer than as a mosque.

Gavrilov supported his motion with the importance of "friendly relations" between Russia and Turkey. He said the opening of the new Grand Mosque in Moscow underscores Russia's respect for Islam. "In the spirit of friendly relations, it would be up to Turkey to take an equal step by returning Hagia Sophia to the Christian Church," Gavrilov said. Russia is ready to send the "best specialists" to Istanbul "to restore this monument of world Christianity," he said. The Russian state is ready to contribute financially and hire renowned Russian architects and scientists for the restoration. "This step would help Turkey and Islam to show that good will prevails over politics," Gavrilov said.

Bartholomew I, Archbishop of Istanbul and Ecumenical Patriarch, also stressed, "If Hagia Sophia is opened for prayer, then it should be converted back into a church." In a map prepared by the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism in 2007, Hagia Sophia appears not as a museum but as a church. This also shows the intention of certain circles who still want to see and have Hagia Sophia seen as a church.

Selina Özuzun Doğan, one of the few Christian politicians to sit in the Turkish parliament for the Kemalist opposition party CHP, found the active use of the Hagia Sophia during Ramadan 2016 "disrespectful. Hagia Sophia is one of the most important symbols of the country's cultural past and the non-religious use is right for this reason, he said. "If you absolutely wanted to restore the building to some original state, then logically you would have to use it as a church again," Doğan said, adding that Hagia Sophia was, after all, originally built as a church and used as such for centuries. Moreover, there is a far greater shortage of Christian places of worship in the country than of Muslim ones, he adds.

Common place of worship

The Armenian Orthodox Patriarch of Constantinople, Sahak II, proposed in June 2020 that Hagia Sophia be transformed into a joint place of worship for Muslims and Christians in the debate over the building's future status.

Mosque

Several times in Turkish history, the conversion into a mosque has been discussed. In 2010, the right-wing nationalist splinter party BBP demanded that the Turkish government open Hagia Sophia for Muslim prayer at the end of Ramadan (September 8, 2010). In late 2013, ahead of Turkey's 2014 local elections, the Islamic conservative government called for Hagia Sophia to be converted back into a mosque with the aim of winning votes from devout Muslims. Hagia Sophia, they argue, is the Islamic symbol of Istanbul. Some critics claim that Atatürk's signature was forged or that the decision was made under foreign pressure. The Anadolu Gençlik Derneği, a pro-government youth organization, held a demonstrative mass prayer with thousands of participants in front of the museum in late May 2014.

As part of the opening ceremony of a new exhibition in Hagia Sophia, on April 10, 2015, Good Friday for Orthodox Christians, an imam quoted suras from the Koran for the first time in 85 years. Members of the government also took part in the ceremony, which was intended to honor the Prophet Muhammad. Parts of the opposition saw this ceremony as another push by the government to turn Hagia Sophia back into a mosque.

Historian İlber Ortaylı argued that the conversion into a museum was something Turkey should be proud of in terms of respect for foreign art. He referred to the former Great Mosque of Cordoba, which he said, unlike the Hagia Sophia, had its structure destroyed by the addition of a Christian church and was still a cathedral. The world would not appreciate Atatürk's decision to turn it into a museum, but first and foremost the appreciation of Turkish society is necessary, he said.

On the occasion of the fasting month of Ramadan in the Islamic year 1437, Hagia Sophia was temporarily reopened as a mosque in June 2016, causing controversy in Turkey and Greece. Ahead of local elections in 2019, President Erdoğan announced the conversion into a mosque. On May 29, 2020, the 567th anniversary of the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople, a cleric recited Quranic verses at Hagia Sophia. In July 2, 2020, after a hearing that lasted only 15 minutes, the Council of State, Turkey's highest administrative court, announced that it would issue a ruling on the matter within 14 days. On July 10, 2020, the court ruled that the 1934 cabinet decision converting the structure from a mosque to a museum had no legal basis and was therefore void. Erdoğan announced that Hagia Sophia would be opened for Muslim prayers. The chairman of the Diyanet religious authority, Ali Erbaş, then announced that work would begin. It is hoped to be ready by July 24, 2020. UNESCO warned Turkey against the high-handed conversion, saying Hagia Sophia's World Heritage status "carries a number of commitments and legal obligations." Greece condemned the planned rededication to a mosque and said it would do "everything it can to ensure that there are consequences for Turkey." The European Union, the United States and Russia called the decision regrettable. The Russian Orthodox Church expressed horror. Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev, head of the Moscow Patriarchate's foreign office, spoke of a blow to Orthodoxy and said "the spiritual and cultural heritage of an entire world should not be taken hostage to a political situation." The rededication will affect Turkey's relationship with the Christian world, he explained, because "for all Orthodox Christians in the world, Hagia Sophia is an important symbol like St. Peter's Basilica in Rome is for Catholics."

Serbian Orthodox Patriarch Irinej, in a statement on July 13, 2020, spoke of a historical injustice and appealed to Turkey to maintain the status of the building. In view of the transformation that has taken place, both Irinej and the President of Serbia, Aleksandar Vučić, expressed the wish on August 20, 2020, that the Cathedral of St. Sava, expected to be inaugurated in October 2020 in the presence of Vladimir Putin, become a "New Hagia Sophia." Vučić said in this regard, "In a special and indirect way, the Cathedral of St. Sava is a replacement of Hagia Sophia, it becomes a kind of New Hagia Sophia with Our Lady above the altar, which is practically an identical copy in the mosaic in Hagia Sophia, as His Holiness Irinej already pointed out."

The World Council of Churches expressed "sadness and dismay" over the decision. The Hagia Sophia was "a place of openness, encounter and inspiration for people of all nations and religions". Until now, it had been a symbol of Turkey's "attachment to secularism" and its "desire to leave behind the conflicts of the past." The Ecumenical Council criticized Erdoğan for "turning this positive sign of Turkey's openness into a sign of exclusion and division." Other voices argue that anyone who hails the end of the Hagia Sophia Museum as a victory over secularism fails to recognize the power-political motives underlying such a decision. At Sunday prayers in St. Peter's Square on July 12, 2020, Pope Francis said he was thinking of "Santa Sophia" and was "sorely struck."

The Hagia Sophia during the blue hour (2013)

.jpg)

Hagia Sophia (2005)

Paul Tournon, Saint-Esprit, Paris 1928-1935

In Sinan's late work, Istanbul's Kılıç Ali Pasha draws most heavily on the model of Hagia Sophia. It is Sinan's mosque that looks most like a church.

Geometries and dimensions of Hagia Sophia were paraphrased in the Cathedral of St. Sava. The distance of the base square as well as dome dimensions were derived, the interior was structured with arcades

.jpg)

Hagia Sophia (1852)

Search within the encyclopedia