Gulag

The abbreviation Gulag refers to the network of penal and labour camps in the Soviet Union; in a broader sense, it stands for the entirety of the Soviet forced labour system, which, in addition to camps and forced labour colonies, also included special camps, special prisons, compulsory labour without imprisonment and, in the post-Stalinist period, some psychiatric hospitals as places of detention. In the broadest sense, the entire Soviet system of repression is meant.

Gulag or GULag in the linguistic usage of the Soviet authorities stands for Russian Главное управление лагерей (abbreviated ГУЛаг, stressed on the last syllable) ![]() or officially also Главное управление исправительно-трудовых лагерей и колоний, transcribed Glawnoje uprawlenije isprawitelno-trudowych lagerej i kolonij, translated "Main Administration of Corrective Labour Camps and Colonies". Initially, this authority was attached to the secret police GPU of the RSFSR. After the founding of the Soviet Union in 1922, the secret police was expanded to include all the then Union republics, following the Soviet Russian model of the GPU, and was renamed the OGPU in 1923. In 1934, the OGPU was incorporated into the NKVD, the Soviet Ministry of the Interior.

or officially also Главное управление исправительно-трудовых лагерей и колоний, transcribed Glawnoje uprawlenije isprawitelno-trudowych lagerej i kolonij, translated "Main Administration of Corrective Labour Camps and Colonies". Initially, this authority was attached to the secret police GPU of the RSFSR. After the founding of the Soviet Union in 1922, the secret police was expanded to include all the then Union republics, following the Soviet Russian model of the GPU, and was renamed the OGPU in 1923. In 1934, the OGPU was incorporated into the NKVD, the Soviet Ministry of the Interior.

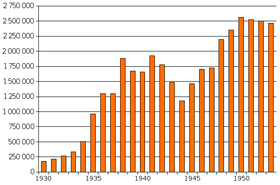

From 1930 to 1953, at least 18 million people were imprisoned in the camps. More than 2.7 million died in the camps or in exile. In the last years of Stalin's life, the Gulag reached a peak of about 2.5 million inmates. In addition, during this period there were about six million people who were exiled as "special settlers" or "labour settlers" to remain in their place of work. During World War II and in the postwar years, the Soviet Union further held some four to six million prisoners of war in GUPWI camps (Главное управление по делам военнопленных интернированных, transcribed Glawnoje uprawlenije po delam wojennoplennych i internirovannych, translated "Main Administration for Affairs of Prisoners of War and Internees") detained and demanded forced labor from them. Immediately after the end of the war, 700,000 inmates of filtration camps were added. Today, experts estimate that a total of around 28.7 to 32 million people had to perform forced labor in the Soviet Union.

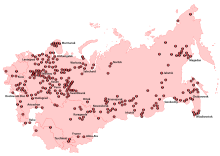

Map with camps of the Gulag

Historical development

Background and history

Ssylka and Katorga

In the penal system of the Russian Empire, banishments (ссы́лка - 'ssylka') and the system of the katorga occupied an important place. In this context, the katorga exhibited a number of typical signs of labor camps: Condemnations, hard physical labor without special expertise, the simplest dwellings, and compulsory labor. It took place predominantly in the sparsely populated, hostile but resource-rich regions of Siberia and the Russian Far East. The epitome of the katorga system in the 19th century was the penal colony on the remote island of Sakhalin. Katorga prisoners, who were sentenced to several years or life imprisonment, often worked in mines and in the timber industry. As punitive categories, ssylka and kartorga concerned convicted political opponents, such as the Decembrists and Narodniki or the Bolsheviks, but also serious criminals.

From 1824 to 1889, 720,000 people were exiled to Siberia. In comparison, the katorga remained a rarer punishment; in 1906 it affected around 6,000 people, and in 1916 this number was 28,600. Literarily, Fyodor Dostoevsky (Notes from a House of the Dead), Anton Chekhov (The Island of Sakhalin), and Lev Tolstoy (Resurrection) dealt with banishment and forced labor, thus making the distant places of imprisonment known in European Russia.

After the February Revolution of 1917, the katorga punishment was abolished. The reintroduced harsh form of punishment katorga (katorshnye raboty, KRT) experienced a new edition in the form of the so-called Stalin katorga from 1943 until the establishment of the special camps of the MWD in 1948. Stalin's katorga camps were camps with a particularly harsh regime for both political prisoners and criminals.

Camps at the beginning of the 20th century

In addition to Russian punishment traditions, the international development of the (isolation) camp is also among the roots of the Gulag. During the Cuban War of Independence (1895 to 1898), Spanish military forces established so-called concentration camps (campos de reconcentración) to separate the Cuban civilian population from insurgents fighting for the island's sovereignty. During the Second Boer War (1899 to 1902), British military forces forced Boer women and children and Africans living in Boer territory into concentration camps. German colonial troops, at the behest of the Reich government under Bernhard von Bülow, isolated members of the Herero and Nama tribes in concentration camps in German Southwest Africa from 1904 to 1908.

POW camp

The First World War saw the proliferation of camps. The POW camps were militarised, the camp infrastructure and the labour of the prisoners were used intensively, and the camp architectures were similar.

The war justified a pronounced friend-or-foe mentality not only on the battlefields. The search for enemies, spies and potential collaborators was also rampant within the belligerent states, for example in the Russian Empire. The experience of camps was omnipresent there as well: interned soldiers of the Russian Empire knew them, as did their relatives. But employers who used the labor of prisoners of war from the Russian camps were also familiar with the camps, as were neighbors and the administrative and guard personnel of such facilities.

Origin and development until the German-Soviet War

Revolution, civil war and terror

In the turmoil that followed the February and October Revolutions, violence spread through Russian civil society. The Bolsheviks fueled it by resorting to terror, with reference to the Jacobins of the French Revolution, along the lines of the Grande Terreur. After the Left Social Revolutionaries left the joint government with the Bolsheviks because they refused to sign the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty (March 3, 1918), the Bolsheviks had supporters of their former partner sent to prisons and concentration camps. Often these concentration camps had previously been prisoner-of-war camps - the military institution thus transformed into a political one.

In August 1918, with the Russian Civil War already months in the making, Lenin invoked the term concentration camp. He called for terror against "kulaks," "popes" and members of the White Army; "dubious elements" were to be locked up in a concentration camp. Since 1917, the Cheka, then the GPU, and from 1923 its successor, the OGPU, developed into the central organs of terrorist violence. After the assassination of Lenin on August 30, 1918, carried out by the anarchist and social revolutionary Fanny Kaplan, a decision of the Council of People's Commissars on September 5, 1918, legitimized the systematic use of Red Terror against "class enemies" and their transfer to concentration camps. In 1921 there were 48 such camps in 43 governorates. In addition to former prisoner-of-war camps, monasteries were also used as concentration camps.

During and after the Russian Civil War, the use of so-called labour armies was of not insignificant importance for the further development of the Gulag system as an economic factor. This was a militarized form of forced labor to which Red Army soldiers were subjected to remedy the negative economic consequences of wartime communism. Parallels between the labour armies and the Gulag can be clearly seen as early as the early 1920s during the 1st period of the labour armies - they existed again from 1942 to 1946. Common features were compulsory or forced labor, the mass use of laborers for hard labor, a military command economy, a bonus system for the fulfillment of labor standards, and food rations linked to this.

Solovetsky

Although the Bolsheviks claimed that prisons and exile had no future under socialism, let alone communism, these instruments of repression remained in use after the Civil War. Ideological concepts of imprisonment initially focused on "education" and "conversion" (perekovka): offenders were to be turned into citizens who welcomed Soviet society and the state. The idea of "reformatory work" took up a great deal of space here; during Lenin's lifetime it dominated competing models aimed at exploiting prisoners' labour. In 1924, the first codification of "reformatory work" took place: in the penal system, work was to play a central role in education. In contrast to Western concepts of imprisonment, the social origin of the delinquent flowed into the type and duration of the punishment; in sentencing and imprisonment, the class approach replaced the principle of equality.

On the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea, about 160 kilometres south of the Arctic Circle, the "original cell of the later Soviet camp system of the Stalin era" was created. Starting from the Solovetsky Monastery there, a camp complex developed from 1923 onwards: the "Solovetsky Camps for Special Use" (SLON). Until its closure in 1939, more than 840,000 people were imprisoned here. The camp complex was intended for serious criminals and political prisoners. The latter were transferred there for this purpose from the so-called "political isolators" (special detention centres for political prisoners) on the mainland. In the 1920s, the SLON held an average of several thousand prisoners. "Political" (members of left-wing parties, anarchists) and "counter-revolutionaries" (survivors of the Kronstadt sailor uprising, representatives of the old regime such as White Guard officers, clergymen, nuns, etc.) constituted the majority of inmates, "criminals" were in the minority. Until 1928/1929 the "politicals" set the tone among the prisoners, then the "criminals" took over. Everyday life in the camp included beating guards, harassment, torture practices, as well as rape and sexual assault of female inmates.

The SLON developed into an experimental field for the future Gulag. In particular, Naftali Frenkel, formerly a prisoner himself, became a reshaper of the camp system in the second half of the 1920s, enforcing economic principles in the use of the labor force. Regardless of whether they were "political", "counter-revolutionaries" or "criminals", the prisoners were extensively used for road construction work and in timber harvesting. Corresponding work was carried out not only in the vicinity of the islands, but also in far-flung areas of the Karelian Republic or Arkhangelsk Oblast. Complaints by Soviet authorities about SLON and its competitive advantages due to cheap prisoner labor were to no avail. Frenkel also linked food rations to labor yield, i.e., to the fulfillment of the given labor standard. He divided the prisoners into three groups according to their physical condition: Capable of heavy labor, capable of light physical labor, and invalids; each of these groups now had its own tasks and work standards. Rations corresponded with the work categories. The differences were considerable: the prisoners in the lowest category received only half the rations that the prisoners in the highest category were entitled to.

In the 1920s, reports about conditions in the Soviet camps repeatedly reached the West because the "politicals" had corresponding connections to exile organizations. The SLON camp complex was also affected. For example, an incident on December 19, 1923, sparked outrage abroad: Guards had fired on a group of political prisoners, killing six of them. In the years that followed, prisoners continued to try to keep foreign countries informed of conditions and events. Communist propaganda, however, drowned them out more and more. Maxim Gorky made his contribution here. After a visit to the Solovetsky Islands on June 20, 1929, he wrote a hymn-like travelogue praising the prisoners' living and working conditions and their successful "reshaping" into useful Soviet citizens. Only six weeks earlier, a commission of the OGPU had come to quite different conclusions. Its report spoke of catastrophic working conditions, torture of prisoners and arbitrary shootings. 13 of the 38 officers of the camp administration were executed.

High officials of the OGPU, the Soviet secret police, also viewed Frenkel's measures with favor. Frenkel's ideas promised to turn costly and unproductive "sit-in prisons" under the jurisdiction of the judiciary into productive and profitable labor camps for the industrialization of the Soviet Union by reducing the cost of housing and feeding prisoners to the bare minimum. Genrich Jagoda, referring to the Solovetsky Islands, called for the establishment of more such camps in the north. In April 1929, a plan to this effect provided for the opening of such camps and placing them under the direction of the OGPU. The majority of prisoners were now no longer subject to the directives of the Ministry of Justice. From 1928 to 1930, the number of prisoners now under the direction of the secret police grew from 30,000 to 300,000.

Special settlements and large buildings after the "Great Reunification

In 1929, Stalin had prevailed against all supposed opponents in the party and had his project of a "Great Turning Point" (Welikij perelom) set in motion. The first five-year plan (1928 to 1932), approved in 1929, provided for the accelerated industrialization of the Soviet Union. Within a decade, the economic and technological level of the industrialized countries was to be reached. Because the money for industrialization could not be raised either by exploiting colonies or by borrowing from abroad, the peasantry had to pay a "tribute," according to Stalin. Grain exports were to finance the equipment and goods necessary to build up industry. The peasants themselves were not to receive a full equivalent for the agricultural products acquired from them. The forced collectivization of agriculture thus became the necessary condition for industrialization, and peasant resistance was stifled in the deculacization campaign.

Deculacization created a large army of special settlers who were forcibly settled in inhospitable regions of the Soviet Union in order to develop them economically. The world of the special settlers was "a kind of middle ground (...) between the free world and the camp world". The sparse settlements in hostile environments, created from nothing with little, were basically peasant settlements under state supervision - without walls, barbed wires and fences. Central infrastructure facilities such as canteens or washrooms were usually absent. Occasionally, the men were separated from the women and children. In these cases, this forced segregation of male workers was only relaxed after the problems with the children and women left behind became increasingly serious. Furthermore, the special settlers were allowed to cultivate their own plot of land. Hunger and deprivation, however, remained the order of the day in these settlements.

The chaotically prepared settlement attempts could end fatally, especially if the special settlers were not peasants who knew about agriculture and the rigors of nature, but "socially harmful and declassed elements" - mainly urbanites. This was the term used by the Soviet authorities to describe groups of people whom they forcibly removed from the streetscape of certain towns (→Tragedy of Nasino).

In 1930/1931, around 1.8 million people eked out an existence in special settlements. Mortality was high: in the northern administrative region alone, around 240,000 people died in 1932/1933. Many people also fled from these settlements. The number of those who escaped between 1932 and 1940 was 600,000. Their destination was either their homeland or the growing and industrializing cities. From the mid-1930s, the importance of the special settlements slowly declined; in 1939, some 1.2 million special settlers were still recorded. During the Second World War, their numbers rose sharply again, as the special settlements filled up with members of those nations whom Stalin suspected of collaborating with the enemy and therefore had them forcibly deported. The number of special settlers in 1953 was 2.7 million.

The White Sea-Baltic Canal built from 1931 to 1933, initially called the Stalin Canal, was the first example of a large-scale infrastructure project implemented through the mass use of forced labor. The novel connection of such large-scale construction sites with the camp system is considered a "turning point in camp policy", and the canal itself was "style-setting" in this respect.

The waterway was to cover 227 kilometres of land, five dams and 19 locks were to be built. Frenkel led the construction work from November 1931 until its completion, OGPU boss Jagoda bore the political responsibility. Because there was hardly any machinery available, the work was done with bare hands - labour became a "bulk commodity". 170,000 forced laborers were used on the construction site, 25,000 of whom died during the large-scale project. Initially, SLON provided the forced laborers, then the BelBaltLag established itself as the warehouse of this canal.

Stalin and his entourage considered the canal a success: the large-scale project was completed within the planned deadline, the mass use of forced laborers, who had been promised reduced prison sentences if they met the specifications, seemed to have proved successful, and the OGPU demonstrated management qualities in Stalin's eyes. However, the new canal was hardly suitable for the intended economic and military purposes because the water depth was insufficient. In this respect it is regarded today as a "symbol of both senseless and deadly excesses of Soviet despotism". Communist propaganda saw things differently. It considered the canal a showpiece of Soviet creative will. Thirty-six authors, including the well-known writers Maxim Gorky, Alexei Tolstoy, Mikhail Shshchenko, Viktor Shklovsky, Vsevolod Ivanov, Demyan Bedny, Valentin Katayev, Bruno Yasieńsky, and Nikolai Tikhonov, wrote a jubilant pamphlet to its fame, praising the "forging" effect of prisoner labor and the overcoming of all natural adversities. The collection of texts appeared not only in the Soviet Union, but also in an English edition. Today it is regarded as a prime example of the "avowed terror" of Stalinism and of the corresponding exploitation of intellectuals and writers.

A comparable development project was the Moscow-Volga Canal, a main project of the Second Five-Year Plan (1932 to 1937), with its DmitLag camp complex near Moscow. From 1932 to 1938 it was the largest Gulag camp ever. It held nearly 200,000 prisoners annually from 1934 to 1936. From mid-September 1932 to the end of January 1938, more than 22,800 DmitLag prisoners died.

Prisoners were also used in railway construction, for example for the Baikal-Amur-Magistrale (BAM). In the associated camp, the BamLag, which opened in November 1932, there were up to 268,700 people. The task of the forced laborers was to prepare the first construction phase of the BAM, which included the execution of civil construction works along the BAM route. They also had to lay a second track for the Trans-Siberian Railway.

The Gulag also played an important role in the development of raw material deposits. In 1929, for example, the so-called Ukhta expedition was launched. Its task was to locate oil deposits in the northwest of Russia. The first base of the expedition gradually became the town of Ukhta. More significant than oil discoveries was the discovery of extensive coal deposits. In a few years the camp point "Rudnik 1" (Mine 1) became the town of Workuta and the center of the WorkutLag camp. In 1938 there were already 15,000 prisoners living in WorkutLag. By 1953, about one million prisoners were to pass through the Workuta camps, a quarter of whom perished. Camps also sprang up elsewhere as a result of the Ukhta expedition, including the UchtPetschLag as early as mid-1931, a camp that continued to expand over the years, often changing its name. In 1932, it held just under 4,800 inmates; by mid-1935, it already held nearly 18,000.

The large camp complexes also included the SibLag, which operated from 1929 until at least 1960. The inmates of the SibLag were employed mainly in the timber industry, agriculture, construction of roads and industrial facilities, and industrial production. Camp prisoners built parts of the cities of Novosibirsk and Mariinsk. The maximum number of prisoners in this camp compound was more than 78,000. Average occupancy varied between 30,000 and 40,000 detainees.

In Dolinka near Karaganda in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, the headquarters of the KarLag had been located since 1931. The prisoners of this camp worked in a number of industries, mainly in agriculture, but also in coal mining. The camp complex included about 10,400 inmates at the end of 1932. At the beginning of January 1936, more than 38,000 prisoners were registered.

Another example of comprehensive peupling and development projects is the NorilLag. North of the Arctic Circle, it functioned from the summer of 1935 as a forced labor camp for the construction and operation of the Norilsk copper-nickel combine, which exploited the non-ferrous metal deposits in northeastern Siberia. The NorilLag convicts also built the city of Norilsk. The inmate population of this camp was 1,200 on October 1, 1935, and steadily increased, reaching about 70,000 to 90,000 in the early 1950s. 270,000 people in total passed through the camp, and 17,000 to 18,000 died during imprisonment.

An extensive forced labor complex was created in the Kolyma region from April 1932. This area included more than the landscapes along the Kolyma River. Again and again, other areas throughout the northeast of the USSR were added to the forced labor complex, until in 1953 it finally reached an extent of 3.5 million square kilometers - one-seventh of the territory of the Soviet Union. Eduard Bersin (1894-1938) served as the first director of the industrial giant Dalstroi and the SevVostLag camp, even though these organizations were formally separate. The directors of Dalstroi, Bersin and his successors, were at the same time plenipotentiaries of party, executive, police and intelligence organs - they were unchallenged rulers of the region. The Communist Party remained without any influence of its own on the territory, in which hundreds of camp points (lagpunkty) wandered on with the extensive exploitation of nature. The reason for the outwardly emphasized separation of Dalstroi on the one hand and SewWostLag as well as its sub- and successor camps on the other hand was the concern that foreign countries would boycott the mined mineral resources - especially gold - after the forced labor had become known. Such an outlawing could have jeopardized the industrialization of the Soviet Union, which, in addition to agricultural products, was financed by gold sales. Dalstroi was also interested in deposits of uranium and tin. Magadan emerged as an economic and administrative center. Between 1931 and 1957 about 880,000 people were imprisoned in the Dalstroi dominion, about 125,000 died in the camps.

Organization

Between 1929 and 1953, 476 camp complexes with thousands of camp points were built. In addition, there were no less than 2,000 colonies for "special settlers", "work settlers", repressed youths, etc. The steady growth of the camp and special settlement system necessitated the reorganization and restructuring of the official administrative structures. In 1934, the OGPU was absorbed into the NKVD, which now had jurisdiction over all camps, special settlements, prisons, and other places of detention in the USSR. Still in 1934, the Main Camp Administration (GULag) was established in this ministry. In accordance with the growing importance of the camps for the Soviet economy, the camps had to fulfill specifications of state economic planning. Important branches of the Soviet economy were reflected in the responsible Gulag branch administrations, for example, for the timber industry, agriculture, mining, railway and road construction. Specialized departments also existed for camp personnel, such as those for cadre management, for informers and repression ("Operative Chekist Administration"), for medical and hygienic matters, for camp administration and supply, or for propaganda, cultural, and educational tasks in the camps.

Over the years, different types of camps and settlements developed: There were transit camps, labor camps, punishment camps, women's camps, camps or "labor colonies" for children and young people, camps for invalids, special camps for scientific research, testing and filtration camps, special settlements, work settlements, and more.

Great terror and forced labor

Many Gulag officials also fell victim to the Great Terror in 1937 and 1938, most notably Jagoda, the former head of the OGPU. Many of his protégés also did not survive, among them Matwei Berman, for many years head of the Gulag authorities, and his successor Israil Pliner (1896-1939). Eduard Bersin died violently, as did Semyon Firin (1898-1937), who had headed the DmitLag. With Firin, another 200 or so DmitLag cadres were executed. They were accused of conspiring against Stalin.

The shootings during the Great Terror, however, affected Gulag prisoners to a far greater extent. At the end of July 1937, NKVD Order No. 00447 "on the repression of former kulaks, criminals and other anti-Soviet elements" alone provided for the shooting of 10,000 people in the Gulag camps. By the end of the Great Terror, the number of prisoners murdered on the basis of this order was 30,178. On the basis of this and a number of other operational orders on ethnic cleansing, NKVD members shot, for example, about 1,000 to 1,800 inmates of the SLON, about 2,000 to 2,900 in Workuta, and about 3,000 to 5,900 in the Dalstroi area.

The Great Terror also shook the system of prisons, camps and special settlements of the Gulag in other ways. The number of inmates increased significantly: from 786,595 on July 1, 1937, to 1,126,500 on February 1, 1938, to 1,317,195 on January 1, 1939. The precarious logistics of the Gulag came apart at the seams because of this. This had consequences for the reception, distribution, supply, guarding and labour use of these masses of prisoners. The camps were overcrowded, the camp regime became harsher, and the productivity of the camps decreased. In 1937, according to official Soviet statistics, 33,499 people died in the camps, special settlements, and prisons. The number of people who died during deportation transports and on routes between Gulag camps also soared by 38,000 between 1937 and 1938. The statistics further indicated that the rate of inmates unable to work due to illness, disability, or emaciation exceeded nine percent in 1938, affecting more than 100,000 persons. In 1939, some 150,000 inmates were unable to work, not including invalids. The Great Terror proved to be a disaster for the Gulag economy, not only for the camp system, but for the entire Soviet economy.

Productivity only increased again under the direction of Lavrenti Beria, who took over the leadership of the NKVD in November 1938 at the end of the Great Terror. His reorganization of the Gulag after 1939 led to the abandonment of the geographical or functional division, and instead it was now organized by branch. Inside the camps, the individual's living conditions were again to be linked to the degree to which he or she met standards, similar to what had been conceived in the SLON in the late 1920s. Individuals were classified according to their level of punishment, occupation, and ability to work. Basically, each prisoner was given a task and a standard that dictated productivity goals. How individual prisoners met their needs for food, clothing, shelter, and living space was to depend only on the degree to which they met their particular standard. Beria's concern was to align every aspect of camp life with predetermined production outcomes. Even when productivity increased, the realities of the camp often looked different: Corruption, embezzlement, theft, fraud, and cheating on norm fulfillment - the so-called tufta - were commonplace; prisoner hierarchy was not dependent on work performance.

Second World War and post-war period

members of enemy nations

From 1939 to 1941, as a result of the Hitler-Stalin Pact and the Soviet occupation of corresponding territories, NKVD employees deported many Poles, Balts and Ukrainians who were considered particularly dangerous to the Gulag, a total of about 170,000 people, plus Moldovans and Belarusians.

The war years following the German invasion of the Soviet Union (22 June 1941) brought further waves of deportations against members of ethnic groups suspected of collaborating with the invaders or acting as the enemy's fifth column. Shortly after the war began, this affected about one million Soviet citizens of German origin, especially those from the Volga German Republic (ASSRdWG). In addition, thousands of German emigrants, mostly former citizens of the German Reich, were caught up in another wave of deportations beginning in November 1941 and lasting until the spring of 1942. The exile destinations for Germans, which for the Soviet authorities since the Anschluss of Austria in 1938 also included Austrian emigrants of the KPÖ or former Schutzbündler, were generally - for security reasons - behind the Urals, predominantly in Siberia and Central Asia. In 1942 the deportees, mainly Russian Germans and ethnic Germans, were mobilised into labour armies and conscripted into forced labour. The so-called "labor armies" were sometimes gathered in the same Gulag camps as regular prisoners. In 1943, deported peoples from the North Caucasus and the Crimea were added: Karachay, Kalmyks, Chechens, Ingush, Balkars, Crimean Tatars, Meskhetians and Kurds.

High mortality rates characterized life in the new settlements and the transports there: 20 to 25 percent of the deportees died by 1948. Not only did the Gulag camps fill up, but the special settlements grew as well. Whereas the number of these settlers had been around one million shortly before the Second World War, by the beginning of October 1945 it had risen to 2.2 million.

Evacuations

Triggered by the surprise attack of the Wehrmacht, the camps in the western Soviet Union were hastily evacuated in the summer of 1941. Due to a lack of transport capacity, this evacuation often took place on foot. The prisoners were forced to make forced marches, often more than 1,000 kilometres. 210 labour colonies and 27 camps were evacuated in this way, affecting 750,000 people. Another 140,000 prisoners from 272 prisons were also taken to eastern parts of the country. Many deportees did not arrive at their destination. Where there was insufficient time for deportations, NKVD personnel summarily murdered the detainees. If German units discovered such murder victims on their advance, they used this for propaganda purposes and for pogroms against Jews - such as in Lemberg or Tarnopol. The National Socialists accused the Jews of being behind all the crimes of the Bolsheviks (→Jewish Bolshevism).

War Years

Although during the war about one million prisoners were released as combatants to the front to compensate for the high losses of the Red Army, the living conditions in the camps deteriorated dramatically. These deteriorations, however, were not a special phenomenon of the Gulag, but a general trend affecting the entire country. The provision of food and shelter for the prisoners was catastrophic in many places. Hunger and epidemics increased, especially cholera and typhus. More than two million people died in the camps and labour colonies during the war. The death rate of prisoners was 20 to 25 percent. The living were also predominantly in poor condition: at the end of 1942, 64 percent of all camp inmates were unable to work or only capable of light work due to health deficiencies.

After the end of the war

While prisoners of war on Soviet territory were generally subject to the "Main Administration for the Affairs of Prisoners of War and Internees" (GUPWI) from 1944 onwards, people convicted of war crimes served their sentences in the Gulag. Due to the expansion of the Soviet sphere of power, the Gulag was filled with people from countries in East-Central Europe as well as from Austria and the Soviet occupation zone after the end of the war. These included people who came from Poland, the Baltic States, or Ukraine and were considered nationalists; often they had experience in partisan struggle; in the Gulag their cohesion was considered great. The number of prisoners also grew because hundreds of thousands of Soviet soldiers who had become prisoners of war or had to perform forced labour, as well as returning civilian workers from the East, were sent to the Gulag. They were considered guilty because they had allegedly committed desertion or collaborated with the enemy. Finally, the extremely repressive anti-theft decrees of June 4, 1947 - a harsh reaction to the famine of 1946/1947 - caused an increase in the number of prisoners. Despite an amnesty for 600,000 prisoners announced in July 1945, the convict population doubled between 1944 and 1949. By the early 1950s, the prisoner population reached an all-time high of 2.5 to 2.6 million, equivalent to four percent of the working-age population in the Soviet Union.

Zenith and crisis

That the Gulag was a significant factor in the Soviet economy was clearly evident in individual branches of production. At the beginning of the 1950s, it accounted for 100 percent of diamond and platinum production, 90 percent of silver production, 35 percent of nickel and nonferrous metals production, one-third of Soviet gold production, 50 percent of all timber production, and 50 percent of coal production. Uranium production, which had military-strategic importance for the construction of the Soviet atomic bomb, came 100 percent from the Gulag and its affiliated enterprises such as Dalstroi. The Soviet Union's first nuclear reactor near Chelyabinsk was built by Gulag prisoners.

In the construction of waterways, river power plants, and other large-scale hydroenergetic projects, the economic importance of the Gulag was also evident. The Volga-Don Canal is a case in point: Here, more than 236,000 Gulag prisoners were employed from 1948 to 1953, but they had access to a much larger pool of machinery than in pre-war projects. Four camp complexes of the VolgoDonStroi provided the convict reservoir. In propagandistic accounts, however, the forced labor of Gulag prisoners was completely omitted. Gulag prisoners were also used in the construction of the Kuibyshev Reservoir, which belonged to the Kuneyevsky camp, where, according to official figures, almost 46,000 people were living on January 1, 1953. The Akhtubinsky camp provided the forced labor reservoir for the construction of the Stalingrad reservoir; at the beginning of 1953 it held more than 29,000 prisoners.

Another large area of use of Gulag prisoners after the Second World War was railway construction, in particular the further construction of the BAM. The Polar Circle Railway, which became famous as the Death Line, as well as the Selichino-Sakhalin railway line are also among them - both large-scale projects that remained unfinished.

In 1952, a total of nine percent of all state investments went into the Gulag. However, this sheer size also concealed problems: The availability and mobilizability of forced labor drowned out weaknesses in labor productivity and acted as a narcotic. Productivity often reached only 50 percent, measured against that of free labor. Forced labor appeared useful where crude and simple work was performed; where specialized knowledge and dedication were required, however, it reached its limits. Despite the Soviet Union's large population losses due to the war, the Gulag administration found no means of using the prisoners' labor sparingly. The aging Stalin also exerted strong pressure by advocating economically nonsensical large-scale projects; such prestige projects based on forced labor seemed to have arisen from Stalin's desire to erect monuments to himself during his lifetime. All attempts to establish incentive systems in prisoner labour failed - not least because they were undermined by the so-called tufta (work for appearances or ubiquitous and systematic norm fraud). Another characteristic of the economic crisis was the Gulag's enormously bloated administrative apparatus. At the beginning of the 1950s, this authority comprised some 300,000 people, two-thirds as guards and one-third as technical and administrative staff. In March 1953, the number of Gulag employees was 445,000; 234,000 of them worked as guards.

The economic crisis was accompanied by changes within the camp society. The rule of the serious criminals among the prisoners, unchallenged since the 1930s, was challenged by the new groups that arrived in the camps after the war: former soldiers of the Red Army as well as Ukrainian, Baltic and Polish "nationalists". They were imprisoned for up to 25 years without any prospect of release, emphasised their cohesion and were therefore difficult to discipline. The guards and the serious criminals were now faced with a dangerous opponent: experienced in war, violence and organization. The authorities reacted to this from 1948 to 1954/1957 by establishing and operating so-called special camps of the MWD (Ossobye lagerja). Here, a harsher detention regime, longer working hours and stricter guard regulations applied; accommodation and care were consistently worse, visits from relatives were forbidden, contact with letters was severely restricted (one to two letters per year) or prohibited altogether. At the beginning of 1953, 210,000 people were in the special camps. This measure did not bring peace. On the contrary, the isolation of the recalcitrant "political prisoners" led to the formation of veritable pockets of resistance. Between 1948 and 1952 there were around 30 hunger strikes, demonstrations, strikes and revolts in the special camps - harbingers of the great uprisings after Stalin's death.

The Gulag after Stalin

"Dissolution" and continuation in a new form

Formally, the main administration of the camps within the MWD was abolished shortly after the XXth Party Congress of the CPSU in May 1956. However, this did not mean the end of the camp institutions, but their reorganization in a new form. First, the individual camps that were not incorporated into the economy were briefly subordinated to the judiciary from October 1956 to April 1957, as they had been in the early 1920s and 1930s. Some camp complexes, such as the one on the Kolyma (Dalstroi) and WorkutLag, were not closed until the early 1960s. The Main Camp Administration (GULAG) became the Main Administration of Corrective Labour Colonies (GUITK) within the USSR Ministry of Justice. In the early 1960s, this was renamed the Main Administration of Correctional Institutions (GUITU) and was again under the MWD. In principle, all the successor organizations of the structure were adhered to the old Stalin's Gulag system, only somewhat milder in the camp regime. This remained essentially the case until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Uprisings

Shortly after Stalin's death, there were major uprisings in the Gulag in the summer of 1953. The GorLag, a special camp near Norilsk, was affected by this from the end of May until the beginning of August 1953. From mid-June to the beginning of August, the prisoners in the Workuta special camp RetschLag (Workuta Uprising) rose up. In both camps, during this rebellion, Western Ukrainians, Poles and Balts took the lead in the actions. Although negotiations took place between the insurgents and representatives of Moscow, the Soviet state power eventually put down the revolts. This violent pacification resulted in eleven deaths, 14 serious injuries and 22 minor injuries in GorLag; in Workuta there were 64 deaths and 123 injuries.

From mid-May to the end of June 1954, the Kengir Uprising took place in StepLag, which also ended in a violent suppression despite negotiations. The death toll here was 35 and 37 respectively, 106 wounded prisoners were added; 40 soldiers suffered injuries. There was also considerable unrest in other camps during this period, for example in the Kuneyevsky camp.

The news of Stalin's death on 5 March 1953, of the uprising of 17 June 1953 in the GDR and of Beria's deposition (26 June 1953) are considered to have triggered the uprisings. Many prisoners attached to this news the hope of a fundamental change in their life situation.

Reforms, amnesties and rehabilitation

Immediately after Stalin's death, Beria restructured the secret police. He assigned responsibility for the Gulag to the Soviet Ministry of Justice. Large camp-industrial complexes were placed under the control of other ministries, such as those for forestry, mining, road construction, and manufacturing. Moreover, Beria had more than 20 large-scale construction projects halted that were based on forced labor. In June 1953, he announced his intention to liquidate the entire forced labor system, claiming that it was economically inefficient and lacked perspective. The number of camps decreased: in March 1953 the Gulag included 175 camps; by April this number had fallen to half. At the end of 1953 it was 68.

Not only the number of camps changed, but also the camp regime. On July 10, 1954, the Central Committee of the CPSU passed a resolution to reintroduce the eight-hour day, the regulations on the daily routine in the camps were relaxed, and prisoners were once again given the opportunity to qualify for a shortened prison sentence through good work. The special camps were dissolved or converted into ordinary work camps. Prisoners were now allowed to write letters and receive parcels without restriction. Even the marriage of prisoners was officially permitted.

After Khrushchev's secret speech at the XX Party Congress of the CPSU on February 25, 1956, in which he addressed Stalinist crimes and pushed for de-Stalinization, the overall administration of the camp system came to an end: as early as May 1956, the Gulag's governing body, the Main Camp Administration, was officially dissolved. This was followed in 1957 by the liquidation of the Dalstroi and Norilsk camp complexes. Three years later, in 1960, there were only 26 camps left in the Soviet Union.

On March 27, 1953, barely three weeks after Stalin's death, 1 to 1.2 million of the 2.5 million Gulag prisoners were granted amnesty. This amnesty covered all inmates serving a sentence of up to five years for official and economic crimes, as well as pregnant women, women with young children, minors, the elderly, and the seriously ill. Those who were considered "counter-revolutionaries" were not amnestied.

The wave of releases in the weeks after March 27, 1953 was precipitous and chaotic: Due to the lack of planning, preparation and control, there were many assaults, debauchery, looting, mass rapes, murders and violent clashes with the forces of order. Removal from the places of detention was slow due to inadequate transport logistics. Many ex-prisoners were subjected to bureaucratic harassment, often already at the place of their detention itself, in order to hinder their departure in this way. Some of the amnestied prisoners therefore remained on the spot; these people now lived as "freemen" near their place of imprisonment. Largely destitute and without the support of family or friends, they saw few prospects for themselves elsewhere. The surprising amnesty and its chaotic side effects caused fear and unrest among the Soviet population.

Even after Beria's end, the wave of amnesty continued. From the beginning of 1954 to the beginning of 1956, 75 percent of the remaining political prisoners were released. By January 1, 1960, the proportion of those imprisoned for political reasons in the camp population had fallen to 1.6 percent.

Those who were amnestied were not automatically rehabilitated. To restore their reputation, the former prisoner or his family members had to undergo bureaucratic procedures. The relevant applications were very often rejected. Even successful applications for rehabilitation were secret in every case and never accompanied by a public apology from the state. From March 1953 to February 1956, the Soviet authorities rehabilitated about 7,000 persons. It was not until Khrushchev's "secret speech" that a change was initiated: By the end of 1956, a total of 617,000 people had now been rehabilitated. Despite this absolute number, rehabilitations remained the exception. For example, the so-called revision commissions, which had been set up immediately after the XXth Party Congress and were active directly in the Gulag camps, had only issued rehabilitation decisions for four per cent of all cases examined by 1 October 1956; in relation to all those released, this was 6.4 per cent.

The revision commissions moved in a contradictory field of forces. While Khrushchev wanted to push ahead with the practice of rehabilitation, the public prosecutor's office, fearing a loss of competence, put the brakes on. The CPSU headquarters, for its part, reserved the right to revise the commissions' verdicts. The commissions often had only a few minutes to examine each individual case. The request for old investigation files alone was lengthy and complicated and could take weeks. Many former prisoners therefore preferred to forego rehabilitation and settle for mere amnesty. The wrangling over competences and the bureaucratic hurdles were compounded in 1956 by the uncertainty of the political leadership following the Poznan Uprising and the Hungarian National Uprising. Accommodating dismissed prisoners in this situation seemed less and less opportune. The pace of rehabilitation slowed markedly until it all but ceased: Only 24 people were rehabilitated between 1964 and 1987.

As compensation for imprisonment, the Soviet authorities often granted the rehabilitated no more than two average monthly wages equal to their earnings before arrest. Despite statements to the contrary, ex-prisoners remained at a disadvantage when it came to finding housing and work. There were restrictions in other areas as well: Deported peasants, for example, remained entirely without recognition of their innocence. Confiscated property was not refunded to rehabilitated persons. The Volga German Republic was not restored, the Crimean Tatars were not allowed to return to their homeland.

A fundamental change came only towards the end of the Soviet Union. On January 16, 1989, a ukase of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet annulled all extrajudicial sentences of the 1930s and from the beginning of the 1950s, at the same time declaring all persons who had been punished under such sentences to be rehabilitated. Politically, the USSR President's ukase "On the Restoration of the Rights of All Victims of Political Repressions in the 1920s to the 1950s" of 13 August 1990 went even further. All repressions committed on political, national, religious and social grounds were for the first time designated as unlawful in this document. It classified the repressions as criminal and a violation of the norms of civilization. The ukase also addressed the victims of collectivization, as well as the persecution of the clergy and the inconsistencies of the rehabilitation process after the XX Party Congress.

On 18 October 1991, a few weeks before the dissolution of the USSR, the law "On the rehabilitation of victims of political repression" - it was adopted by the Russian Federation - regulated the future understanding and procedure: All victims of political persecution since the October Revolution of 1917 were addressed. The USSR was described as a totalitarian state, state terror was condemned, sympathy was expressed to the victims and relatives. The law stipulated that politically persecuted persons, persons convicted by extrajudicial bodies, exiles, special settlers, forced labourers, deported peoples, exiled family members and other relatives were to be rehabilitated. It also clarified how to apply for and process such applications. It also regulated compensation payments and privileges for victims concerning local transport, rents and medical care. At the end of 2001, 4.5 million political prisoners had been rehabilitated in Russia.

Dissident

Political repression also characterized the post- or neo-Stalinist Soviet Union of the Brezhnev era. However, its nature and scope were not comparable to the repression that had been part of everyday life in the decades before. The number of politically persecuted persons in the USSR from 1957 to 1987 was between 8,000 and 20,000. In 1975, Amnesty International estimated the number of imprisoned dissidents at 10,000 out of a total of one million prisoners in the USSR. This group included people who had sympathised with the Hungarian uprising, Jews who had been refused entry to Israel, Baptists, members of special religious groups, politically maladjusted children and relatives of "enemies of the people", and many intellectuals.

Special camps for political prisoners of the post-Stalinist era were the Perm 36 camp and the Dubraw camp in Mordovia. In the 1970s, the Vladimir Prison took over such a function. Occasionally, prisoners died from the conditions of detention and from hunger strikes in which they rebelled against imprisonment. The deliberate psychiatrization of dissidents led to psychiatric hospitals being misused to imprison political prisoners, such as the Serbsky Institute in Moscow. Mikhail Gorbachev put an end to such practices and announced a general amnesty for all political prisoners in the USSR at the end of 1986.

Remains of the polar railway line between Salechard and Nadym (2004)

Gold mine on the Kolyma (1934)

Construction work on the White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal (summer 1932)

20 June 1929: Maxim Gorky (fourth from the right), surrounded by functionaries of the Soviet secret police OGPU, visits the Solovetsky Islands.

Development of prisoner numbers in the Gulag (1930-1953)

Photo of the Solovetsky Monastery, summer 1972

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the Gulag and how long was it in operation?

A: The Gulag was a network of "slave labor" camps run by the Soviet Union from the 1920s to the 1950s.

Q: Why did the Soviet Union imprison people?

A: The Soviet Union imprisoned people who spoke out against it or were otherwise considered dangerous.

Q: Did Imperial Russia also have a system of prison camps?

A: Yes, Imperial Russia had a similar system of prison camps.

Q: Who set up the Soviet camp system?

A: The Soviet camp system was set up under Vladimir Lenin.

Q: When did the Gulag reach its peak?

A: The Gulag reached its peak during Joseph Stalin's rule from the 1930s to the early 1950s.

Q: What were the yearly mortality rates in the Soviet concentration camps?

A: According to Nicolas Werth, the yearly mortality rate in the Soviet concentration camps varied, reaching 5% (1933) and 20% (1942–1943) and dropped in the post-war years to about 1 to 3% per year at the beginning of the 1950s.

Q: How many prisoners were in the gulags by 1936?

A: By 1936, there were 5,000,000 prisoners in the gulags.

Search within the encyclopedia