Greek government-debt crisis

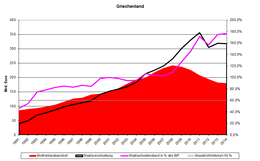

The Greek sovereign debt crisis (also Greek financial crisis and Greek depression) is a crisis of the national budget and economy of the Republic of Greece that has been ongoing since 2010. Following the elimination of national currencies and the associated exchange rate mechanism after the introduction of the euro, the development of appropriate internal adjustment mechanisms in the euro countries had failed. One year before joining the euro zone in 2001, Greece's public debt was already 104.4% of gross domestic product (GDP). During the global financial crisis starting in 2007 and the Karamanlis government's bank bailout program, Greece's public debt ratio rose further from 107.2% (2007) to 129.7% (2009).

In October 2009, newly elected Prime Minister Giorgos A. Papandreou (PASOK) announced upwardly revised debt data (from 3.7% to 12.7% of GDP) and other poor economic data. Methodological shortcomings of the Statistical Office of Greece (ESYE) and possible political influence on the statistics prompted this correction. The new data caused Greek government bond yields to rise sharply. That same year, Papandreou asked IMF chief Strauss-Kahn to launch an aid program for Greece, which the latter refused, referring the prime minister to his EU partners. The latter prepared a much larger loan package with the IMF, which Papandreou originally wanted to accept only after a referendum, which in turn was rejected by some of the most important euro partners. The Sarkozy and Merkel governments demanded that Greece either accept the loan terms without a vote or leave the eurozone. Since the government did not feel able to repay loans that were due, Papandreou gave in, and Greece applied for the prepared three-year aid package without a prior referendum on April 23, 2010.

An IMF loan of 30 billion euros for Greece was initially increased by the EU to a total volume of 110 billion euros and declared as a measure to save Greece and the euro. While the IMF loans for Greece (also known as "emergency loans") have only been corrected slightly to 32 billion euros to date (as of May 2018) due to inflation, the EU and ECB increased the share for the euro rescue (so-called "emergency guarantees") to 290 billion euros (= euro rescue umbrella) in what are now three loan packages, despite reservations on the part of the prime ministers Papandreou, Samaras and Tsipras, who were each involved in turn. Thus, the financial framework granted by the three institutions involved - the so-called "troika" - is now 322 billion euros, ten times as high as the aid program launched by the IMF. Of this, 277.6 billion euros were ultimately disbursed (as of September 2018). 31.9 billion euros of IMF credit went to the Greek state and 245.7 billion euros of so-called EU guarantees to European banks.

This was followed in March 2015 by the purchase of bonds from euro states by the European Central Bank (ECB). Among other things, the "institutions" and the Greek government decided on comprehensive budget cuts. The measures included wage cuts, for example in the public sector and in the minimum wage, general budget cuts and an increase in value-added tax. In addition, privatisations were carried out. In addition, measures were initiated to improve the Greek administration. These include the implementation in May 2010 of the administrative reform according to the Kallikratis program, the numerical registration of all persons working for the state and the review of pension payments to those who may already be deceased. The consolidation of the numerous local land registry offices (υποθηκοφυλάκειο "mortgage office, land registry"), which has been underway for years, into a national cadastre of all the approximately 3.6 million properties is to be completed by 2020[obsolete].

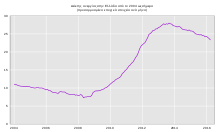

Greece was in recession from 2008 onwards, losing around 26 percent of its real (price-adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP) by 2013. In 2014, there was a minimal gain of 0.4 percent in real GDP. The relative debt level - despite debt cuts in 2012 and despite or due to imposed measures by the Troika - increased from 107.2% to 177.1% of shrinking GDP from 2007 to 2014. Greece has been in deflation since March 2013. Unemployment has risen sharply to around 26 percent in 2014, and problems had increased sharply in the health sector, among others.

On January 25, 2015, there was a change of government in Greece. The new governing party SYRIZA initially continued negotiations on the second program for five months. On the night of June 27, 2015, head of government Alexis Tsipras broke off the negotiations and scheduled a referendum. The very next day, parliament overwhelmingly decided to hold the referendum. As a countermeasure, ECB chief Mario Draghi immediately stopped capital transfers to Greek banks, so that Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis, for his part, was forced to introduce capital controls. In June 2015, foreign transfers were placed entirely under government supervision and released only in exceptional cases. Cash withdrawals by banks were restricted to €60 per day. These restrictions mainly affected the self-employed and businesses; the majority of the population supported their government's referendum, voting 61.3% against the ECB and against EU partners. Tsipras then surprisingly made a U-turn on election night, which Finance Minister Varoufakis refused to support and resigned.

On July 12, 2015, eurozone leaders unanimously agreed on framework conditions for the start of negotiations on a third aid program and Athens received a bridging loan of 7.16 billion euros from the EU bailout fund EFSM, which had previously not been used for several years. The euro finance ministers approved the third aid package on August 19, 2015. The third package was worth 86 billion euros and expired in August 2018. It was implemented through the ESM. On August 20, Alexis Tsipras announced his resignation to legitimize the revision of his position through a re-election. In the September 2015 general election in Greece, Tsipras again emerged victorious and continued in coalition with the ANEL party.

The third aid program for Greece, which expired in August 2018, was not continued. The prime minister had closed it prematurely, even before the funds provided had been used up. Of the 86 billion euros originally agreed, Greece finally accepted to pass through only 55 billion euros to the banks. Instead, Tsipras announced that his country would manage without European aid programs in the future. The final payment to Athens of 15 billion euros and a postponement of loan repayments by ten years were agreed by the eurozone finance ministers.

Euro bills and Greek euro coins

Origin and course

Until the change of government in 2009

Greece joined the euro area on January 1, 2001. In 2004, Eurostat issued a report stating that the statistical data provided by Greece could not be correct. This was attributed to the fact that the Statistical Office of Greece (ESYE) had incorrectly evaluated the data available to it and that the authorities and ministries had supplied the office with distorted data. Against this background, Eurostat published a report in November 2004 on the revision of Greek deficit and debt figures, according to which incorrect figures had been reported in eleven individual cases in the years before 2004.

In January 2010, the European Commission again reported methodological deficiencies in fiscal statistics at the ESYE, a lack of political control and political influence on statistical data in its "Report on Greek Statistics". Since July 2010, a new, government-independent statistical authority, ELSTAT, has been in place.

According to reports in Der Spiegel and the New York Times, U.S. banks such as Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan had helped various euro countries such as Italy and Greece to conceal the extent of their national debt over the past ten years. New borrowing had been booked as currency swaps, which were not counted as government debt. The use of financial derivatives for government financing was not regulated until 2008. Following regulation by Eurostat in 2008, the Greek government did not comply with the reporting requirements when subsequent reporting of such transactions was requested.

According to a report by Bloomberg Business, the Greek government was able to borrow more than 2.8 billion euros via a currency swap deal concluded with Goldman Sachs in 2001. With the help of fictitious exchange rates, this deal was able to hide approximately two percent of Greek government debt on the balance sheet. However, the deal turned out to be disadvantageous for the Greek government, probably also due to its lack of transparency and complexity, so that a renegotiation was scheduled just three months after it was concluded, resulting in a deal with inflation-linked derivatives. However, these subsequently turned out to be equally unfavorable for the Greek state, so that in August 2005 the Greek government negotiated with Goldman Sachs for the repurchase of the entire bonds by the Greek central bank. The repayment of these derivatives eventually amounted to 5.1 billion euros, for which over-the-counter interest rate swap transactions were entered into. Goldman Sachs reportedly received 600 million euros for executing this transaction. Other reports speak of future expected revenues, for example from airport fees and lottery winnings, being assigned.

From the change of government to the outbreak of the crisis

In the parliamentary elections on October 4, 2009, the PASOK party won an absolute majority of seats in Parliament with a 43.9 % share of the vote. Two days later, Giorgos Papandreou was sworn in as the new prime minister. The spending increases in the social sector previously promised to voters by PASOK could not be financed. On October 20, 2009, the new finance minister, Giorgos Papakonstantinou, declared that the 2009 budget deficit would not be around 6 percent of GDP, as stated by the previous government, but probably 12 to 13 percent. This far exceeded the agreed 3 percent new debt limit. The pledge made by the previous government in April 2009 as part of ongoing deficit penalty proceedings to reduce its 2009 public deficit to 3.7 percent (of GDP) could therefore not be kept. As a result, Papandreou contacted IMF chief Strauss-Kahn a month after his election as prime minister and, according to his own account, asked for technical assistance, which the IMF chief refused and referred to the EU. Strauss-Kahn later portrayed the conversation in the press in a different light; at the time, he said, it was about financial aid. Around the same time, in an interview with the ALTER channel, Antonis Samaras, the incoming leader of the ND, accused the new government of amending the planned 2009/2010 budget in such a way as to anticipate 2010 expenditures and shift revenues from 2009 to 2010. As a result of these deliberate (but legal) budget changes, the 2009 deficit shot up from the originally calculated level of around 8% to 12%. The Supreme Court dealt with this matter in 2016 and overturned a previous court ruling in its decision 1331/2016. In doing so, it followed the prosecution's complaint that the Papandreou government had artificially revised the 2009 government deficit upward after the fact and that the head of the Greek statistics authority ELSTAT covered up this correction in order to deliberately drive Greece into the memorandum.

The government in Athens agreed with the EU to report to Brussels every two to three months on its savings successes. An ambitious target was set for Greece to reduce net new debt to below the three percent of gross domestic product stipulated in the stability and growth pact by 2012. At a special EU summit in Brussels on Feb. 11, 2010, Papandreou was urged to implement drastic austerity measures to avert national bankruptcy. The expectation of the summit participants that declarations of solidarity with Greece would be enough to calm the financial markets was not fulfilled. After lengthy controversy over the form of the aid measures, the heads of state and government of the euro states agreed at the end of March 2010 to provide Greece with financial support.

| Rescue Package I for Greece (2010-2013) | |||

| Funders | Commitments | Paid out | Transfer to 2nd program |

| Euro countries | 77,3 | 52,9 | 24,4 |

| IMF | 30,0 | 20,1 | 9,9 |

| Total | 107,3 | 73,0 | 34,3 |

| Source: EU Commission. When it became known that the Troika was planning a second loan package, the prime minister ended the current first one prematurely. He thus prevented the transfer of the remaining €24.4 billion and waived €9.9 billion in loans, instead announcing a referendum. Only after Papandreou was toppled was the EU able to put together the second package. The rejected aid money totaling €34.3 billion was imposed on the Samaras government as contractually agreed following the signing of the second loan package. | |||

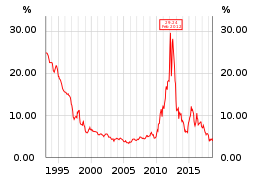

Imminent insolvency and call for help to IMF and EU

Following Strauss-Kahn's rejection of IMF support and the subsequent protracted negotiations with the troika of IMF, EU and ECB, risk premiums for long-term Greek government bonds climbed to new record levels. Finally, on April 23, 2010, the Greek government officially applied for financial aid. Under the leadership of Strauss-Kahn, the troika agreed with Papandreou on May 1-2, 2010, on an IMF loan of €30 billion and a guarantee by EU countries of €77.3 billion this time on condition that Greece implement a rigorous austerity program. To prop up banks holding Greek government bonds, the European Central Bank has been accepting Greek government bonds in full par value as loan collateral since May 3, 2010, even though their creditworthiness is rated low by rating agencies.

However, the aid agreed for Greece was not enough to permanently calm the markets. Risk premiums for Greek government bonds continued to rise. In view of these developments, European heads of state and government agreed at a summit meeting (on May 7, supplemented by a meeting of finance ministers on May 9 and 10, 2010) to set up the European Financial Stabilization Facility (EFSF), which is intended to prevent the imminent insolvency of a eurozone member state if necessary.

Economic and Political Consequences of the First Memorandum

The economic situation deteriorated as a result; insolvencies in the private sector and the unemployment rate (rate increase from 8.5% to 12%) increased. Investments, GDP and thus the tax revenues based on them declined. The risk premiums on Greek government bonds determined on the financial market rose again and in September 2010 almost reached the level of the crisis peak in May.

In Greece, economic output contracted by 4.5% in 2010 (recession). To counteract this, the Greek government asked the European Commission to release certain subsidies for Greece from the EU structural funds in a simplified way. Greece was previously unable to draw on these funds, which amounted to €15.3 billion, as the country was unable to raise the necessary equity contribution as a result of the austerity measures.

In the first half of 2011, protests against the austerity measures adopted increased in Greece. The largest opposition party at the time, Nea Dimokratia (ND), as well as several smaller opposition parties, opposed the downsizing of the civil service and the announced privatization of state-owned enterprises. As early as November 2010, this led to a split from ND, with reform-minded party members founding the new party Dimokratiki Symmachia. Conflicts also arose within the governing faction of PASOK over the austerity course, which some deputies did not want to continue to support. On May 27, the Greek Parliament rejected a government proposal on further austerity measures in a vote. The EU then demanded a bipartisan consensus from the Greek parliament on debt reduction and made further aid conditional on the Greek parliament passing a new austerity package. The European People's Party also increased pressure on its member party ND.

At the end of June 2011, Greek Prime Minister Papandreou reshuffled his cabinet and appointed, among others, former Defense Minister Evangelos Venizelos as Minister of Economy and Finance. On June 29, against the votes of most ND deputies, the Greek Parliament approved a new austerity package that the member states had named in the European Council as a precondition for further aid measures.

In the first half of 2011, new Greek debt amounted to just under 14.7 billion euros - planned for the whole of 2011 was around 16.7 billion euros. At that time, Greece had debts of more than 350 billion euros. At the end of 2010, Greek government debt was 142.8% of GDP; for the end of 2011, the EU Commission expected it to be around 157.7% of GDP.

At a special summit on July 21, 2011, the euro countries agreed on a second bailout package for Greece despite Papandreou's misgivings. Because of the far-reaching consequences for citizens of this second, significantly larger borrowing, Papandreou once again announced that he would let citizens decide in a referendum on the EU's way out of the crisis and stopped further borrowing of EURO bailout loans. The EU saw its way as having no alternative and expressed massive reservations about the referendum. It finally denied Papandreou further support, so that he withdrew the referendum and stepped down as prime minister. Just 2 weeks later (November 10, 2011), a government of EU technocrats was installed in Athens for six months, which immediately called for the next tranche of the first loan package. After that, the bailout package was stopped (after only 73 of the planned €107.3 billion), and instead the second loan package was prepared by the EFSF and the IMF in the amount of €130 billion plus debt cut. Shortly after it was signed by the new Prime Minister Antonis Samaras, it turned out that he also had to call in the unused €34.3 billion from his predecessor

Consequences of the First Memorandum for Democracy

Giorgos Papandreou had signed a memorandum with the three troika institutions, the IMF, the EU and the ECB, on May 1, 2010. Under pressure from his EU partners, he had previously renounced a referendum and, in addition to the requested IMF loan for Greece, a much larger package was agreed to rescue banks in other EU countries (the so-called euro rescue). For this, he was awarded the Quadriga Prize together with Wolfgang Schäuble on German Unity Day 2010 for his "strength of truthfulness." Papandreou's laudation was given by Josef Ackermann.

The next year, Schäuble announced a second euro rescue package without consultation, whereupon Papandreou - notwithstanding his award

shortly before - immediately put all further money transfers for European banks on hold. With his announcement on October 30, 2011, of his intention to hold a "binding" referendum later that year, the prime minister posed with the words, "We trust the citizens, we trust their judgment, we trust their decision. This is an act of democracy. We have a duty to promote the role and responsibility of citizens" openly opposed the agreements. Shortly thereafter, he was forced to resign under domestic and foreign political pressure, and a former Goldman Sachs employee and ECB vice president was installed without election. Since 2010, the Quadriga Prize has no longer been awarded.

Both the provisions of the loan agreements and the form of their implementation have met with legal criticism. Parliamentary involvement - the Greek constitution requires a three-fifths majority for the ratification of such far-reaching international agreements - was limited. A law was passed by a simple majority, according to which the treaties are valid from the moment they are signed. In the opinion of constitutional lawyer Giorgos Kassimatis, this procedure constitutes a breach of the constitution. In his view, the loan agreements violate the basic democratic and social rights of Greek citizens and property rights secured in the Greek constitution, as well as state sovereignty, for example by completely tying up all Greek state assets. An expert opinion commissioned by several European trade union organizations and prepared by the Bremen-based legal scholar Andreas Fischer-Lescano primarily problematizes the lack of legal binding of the EU institutions when concluding the loan agreements. The constitutional law expert Kostas Chrysogonos criticizes the fact that, in the course of implementing the terms of the loan agreements, laws are increasingly being enacted by decree and emergency law is being applied in labor disputes.

Parliamentary elections 2012 and further development

| Rescue Package II for Greece (2012-2014) | ||

| Funders | Commitments | Paid out |

| EFSF | 144,6 | 130,9 |

| IMF | 19,8 | 11,8 |

| Total | 164,4 | 142,7 |

| Source: BMF/EFSF; as of March 2018 | ||

Early parliamentary elections were held in Greece on May 6, 2012. Both major parties, Nea Dimokratia (ND) and the social democratic Panellinio Sosialistiko Kinima (PASOK), suffered heavy losses of votes; together, neither had an absolute majority or governing majority in parliament. The neo-Nazi and racist Chrysi Avgi entered parliament for the first time, as did the right-wing populist Anexartiti Ellines and the left-wing Dimokratiki Aristera. Alexis Tsipras' radical left-wing SYRIZA surprisingly became the second strongest party. Tsipras' attempt to form a government failed; Evangelos Venizelos, leader of PASOK and finance minister, was then given the job. His attempt also failed.

Andonis Samaras formed a new government (Samaras Cabinet) shortly after the June 17 parliamentary elections. It was supported by three parties (Conservatives (ND) Socialists (Pasok) and Dimokratiki Aristera) until June 2013; from then on by ND and PASOK.

In December 2014, the Samaras government failed to have a new president elected in parliament: the candidate did not receive the required majority in any of three rounds of voting (more here). After the failure of the third round of voting (December 29), the President of the Republic had to dissolve the Parliament within ten days and call a general election. The election took place on January 25, 2015.

Parliamentary elections 2015 and further development

| Rescue package III for Greece (2015-2018) | ||

| Funders | Commitments | Paid out |

| ESM | 86,0 | 55,2 |

| Total | 86,0 | 55,2 |

| Source: BMF/EFSF | ||

The early parliamentary election of 2015 was won by the left-wing SYRIZA under party leader Alexis Tsipras with a surprisingly high share of the vote of 36.34 % (2012: 27.77 %). After Tsipras and Panos Kammenos were able to agree on a coalition government between SYRIZA and ANEL (Tsipras Cabinet I), he was sworn in as Greek prime minister the day after the election.

On August 20, 2015, Tsipras announced his resignation, so elections were held again in Greece on September 20, 2015. Syriza obtained 35.46% of the vote, the conservative Nea Dimokratia 28.10%, the radical right-wing Chrysi Avgi (Golden Dawn) 6.99%, the Dimokratiki Symbarataxi (electoral alliance of PASOK and DIMAR) 6.28% and the right-wing populist ANEL (Independent Greeks) 3.69%. Tsipras continued the coalition with ANEL (Tsipras II cabinet).

On December 9, 2016, Prime Minister Tsipras announced plans to make one-time payments totaling 617 million euros to around 1.6 million Greek pensioners with a monthly pension of less than 850 euros. On December 15, 2016, the Greek parliament approved this plan. Other euro state governments criticized that the measure had not been agreed with them. The euro bailout fund ESM subsequently halted the debt relief measures agreed shortly before.

Gross domestic product (GDP), public debt in billions of euros and in relation to GDP. Own calculations based on the AMECO database.

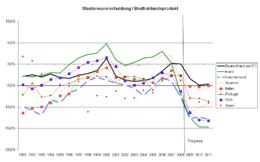

General government net lending/borrowing as % of GDP, according to AMECO data

Interest rates for long-term bonds issued by Greece between 1993 and 2018

Repayment

The agreements between Greece on the one hand and the troika of IMF, ECB and EU on the other to tackle the European financial crisis include very different measures.

IMF loans

Traditionally, the IMF offers the requesting government so-called "technical" assistance together with a medium-term bridging loan. Technical assistance includes the joint elaboration of an austerity plan, which would hardly be politically enforceable by the elected government on its own. Thus, in consultation with the applicant, the measures are formulated in a memorandum as conditions for the loan.

While the technical assistance provided to the Papandreou and Samaras governments met the usual IMF standards, the associated loan was unusually high, totaling €31.9 billion. Repayment of the loan, as well as interest payments, was clearly regulated. Repayment began in 2013, still under the Samaras government. The first loan package of €20.1 billion was finally repaid in 2016 under the Tsipras government. Repayment of the second IMF loan package of €11.8 billion is already underway and is expected to be completed by 2026. A third IMF loan to Greece under the third memorandum has not been agreed. Neither the Greek finance minister nor the IMF chief saw any need for this.

Payments for the euro bailout

The situation is quite different for by far the largest item in the agreements, the €290 billion of European taxpayers' money for the so-called "euro rescue". Here, there is some confusion as to whether the EU countries will get their money back at all, and if so, in what form. While the press reports controversially about this, politicians seem to avoid a clarifying word here. Former Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis hinted at precisely this problem with his refusal to sign a third memorandum. He expected his colleagues in the Eurogroup to pre-determine the timetable for the formal write-off of these book credits and to disclose it to the peoples. But because this, too, is politically unenforceable - this time with the voters of the 27 EU partners - the Eurogroup is taking the position that a refund would indeed be made. On the other hand, it cautiously argues that any relief would only be up for discussion after the third program is completed as of August 20, 2018. The IMF, on the other hand, has been announcing increasingly clearly since the end of the first program and in the recent past that the debt cut would now be forthcoming.

Follow

Retroactive effect on the EU

The development of the Greek financial crisis and the approach of the EU partners had a serious impact on the decision of the British in their Brexit referendum in 2016. In an article in the English Daily Express from July 2015, Albert Edwards, global strategist at Société Générale, is quoted as saying: "... this could now tip the balance for the UK's in/out referendum on EU membership...". Edwards speculated that the British left was running into argumentation problems because of the humiliation of Tsipras by his EU partners. After all, it was precisely the Labour Party that had declared EU membership to be "progressive" for years. Now the party base would organize against membership. Edwards, until then an EU supporter himself, would now probably vote to leave, and he recommended that investors prepare for a possible British exit from the EU.

Yanis Varoufakis is quoted in a BBC program by host Andrew Neil as saying that Brussels is to blame for the dissolution of the EU through authoritarian measures. However, when asked whether the handling of the financial crisis had any influence on the separatist developments in Scotland and Catalonia, he gave a differentiated answer. Whereas in Scotland nationalism had a historical tradition, in Catalonia the separatists had only become a force capable of winning a majority as a result of the handling of the crisis of formerly only 10-15%. He criticized the decision of the Madrid government, in 2010, to curtail Catalonia's autonomy and Juncker's subsequent statement that this was an internal Spanish matter.

Economic consequences

After a drastic widening of the budget deficit in 2008 and 2009 (negative budget balance), it fell again in 2010 and 2011, but in 2011 it was still above the already very high level of 2007. The primary balance, i.e. the budget balance excluding interest expenditure on existing debt, was also still negative in 2011. Similarly, primary expenditure is defined as government spending excluding interest payments on existing debt.

| Development of government revenue and expenditure | |||||||||||

| # | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

| Nominal GDP (billion euros) | 223,16 | 233,20 | 231,08 | 222,15 | 208,53 | 191,20 | 180,65 | 177,94 | 175,69 | 174,20 | 177,74 |

| Government revenue (total revenue) (% of GDP) | 40,7 | 40,7 | 38,3 | 40,4 | 42,3 | 46,6 | 49,1 | 47,0 | 47,9 | 50,2 | 48,8 |

| Government expenditure (total expenditure) (% of GDP) | 47,5 | 50,6 | 54,0 | 51,5 | 51,9 | 55,4 | 62,3 | 50,6 | 55,4 | 49,7 | 48,0 |

| Primary expenditure (% of GDP) | 42,8 | 45,5 | 48,3 | 44,6 | 43,4 | 41,7 | 43,3 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Budget balance (budget balance/net lending) (% of GDP) | −06,8 | −09,8 | −15,6 | −10,7 | −09,5 | −08,8 | −13,2 | −03,6 | −07,5 | +00,5 | +00,8 |

| Primary balance (primary balance/net lending) (% of GDP) | −02,0 | −04,9 | −10,4 | −05,0 | −02,3 | −03,7 | −09,1 | 00,4 | −03,9 | +03,7 | +04,0 |

| Gross consolidated debt (billion euros) | 239,30 | 263,28 | 299,69 | 329,52 | 355,17 | 305,09 | 320,51 | 319,72 | 311,67 | 315,04 | 317,41 |

| Development of the labor market | |||||||||

| # | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

| Population (in millions) | 11,036 | 11,061 | 11,095 | 11,119 | 11,123 | 11,086 | 11,004 | 10,927 | 10,812 |

| Employed persons (in millions) | 4,564 | 4,611 | 4,556 | 4,390 | 4,054 | 3,695 | 3,513 | 3,536 | 3,604 |

| Unemployment rate | 8,40 % | 7,75 % | 9,60 % | 12,73 % | 17,85 % | 24,43 % | 27,48 % | 26,50 % | 25,00 % |

High current account imbalances prevail in the euro zone. Greece was particularly affected by these problems and was not prepared for the euro crisis; higher government debt also left it with less room for maneuver than other countries in responding to the financial crisis starting in 2007. Moreover, according to economist Manolis Galenianos, the Greek governments of the time had taken the wrong measures after the onset of the financial and euro crises. The wrong measures to address this "twin deficit" have led to high social costs. Likewise, he says, the response of other European governments was wrong because they initially ignored the current account deficits and did not help Greece regain international competitiveness. Other current problems cited are the lack of credit domestically in Greece for investment and the lack of demand for products in other euro countries as a result of restrictive fiscal policies.

Since 2009, the public debt ratio has skyrocketed (from 129% in 2009 to 164% in 2011). Public sector salaries fell by 30% from 2009 to 2011, pensions by 10%. The total number of state employees fell from 768,009 in 2010 to 712,157 in February 2012.

According to EU data, in the period from 2010 to 2011, half of the competitive gap created from 2000 to 2009 was made up.

According to a 2012 World Bank report, Greece was among the ten countries worldwide that had improved business conditions for companies the most in 2011; only seven countries had made greater efforts. While urgent reforms had been tackled and great progress had been made, further reforms would have to be implemented in the coming years.

While some trading companies withdrew from the country, other activities expanded, as evidenced by Unilever's production of 110 different products for export (2010) and the new Hewlett-Packard distribution center for Europe, Africa and the Middle East in Piraeus.

In 2012, Rolf Langhammer of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy warned creditor institutions that there was nothing to renegotiate or readjust in view of the lack of compliance with Greek commitments. According to the first aid package of 2010, budget consolidation through tax increases and spending cuts of 30 billion euros was foreseen from 2014. Dirk Meyer (Chair of Regulatory Economics, Helmut Schmidt University of the Federal Armed Forces) points out that this amounts to about 13% of Greek GDP and is therefore illusory in terms of the amount. The practice of all aid programs has shown that Greece does not or cannot keep its promises.

Rating agencies and financial markets

Even before the start of the Greek budget crisis, Greece as a debtor was not rated with top marks by the rating agencies. The three major rating agencies Standard & Poor's, Fitch Ratings and Moody's successively lowered their rating codes over the course of the crisis, signaling to the financial markets an increased default risk for loans and government bonds issued by Greece.

On June 14, 2011, the rating agency Standard & Poor's lowered its rating for long-term Greek government bonds by three notches to CCC. Greece thus had the worst rating of all rated countries in the world since June 2011.

In March 2012, Greece was classified as insolvent by both the rating agencies and the ISDA.

In the course of the financial crisis, the Athex Composite Share Price Index, the benchmark index of the Athens Stock Exchange, lost massive value. The leading index fell to below 500 points in May 2012, its lowest level in 20 years. A gradual recovery began in June 2012, and the index rose to over 1,000 points by February 2013. At the beginning of May 2013, the index had reached 970 points.

On December 18, 2012, Standard & Poor's upgraded Greece several notches to B- and B (long-term and short-term government bonds, respectively). On May 14, 2013, Fitch gave Greek long-term government bonds a B- rating, while short-term government bonds received a B.

Economic policy consequences in Greece

In polls conducted immediately before the vote on the austerity package in May 2010, a majority of Greeks were in favor of it. In November 2010, the ruling socialist party PASOK won the second round of local elections, including the city halls of Athens and Thessaloniki for the first time in 20 years. Nevertheless, there were demonstrations in the city center and other protests: for example, banners were placed on the steep face of the Athens Acropolis. These peaceful actions were mainly carried out by trade unions and communists. In contrast, during demonstrations against austerity plans on May 5, 2010, autonomists set fire to a bank building with incendiary devices, killing three people.

In the course of the austerity measures, the protests became increasingly violent. In 2011, for example, there were numerous demonstrations that repeatedly led to confrontations with the police and, in June 2011, to an occupation of Syntagma Square in front of the Athens Parliament building that lasted several weeks. In addition, from January to June 2011 there were four general strikes, some lasting several days, against the austerity measures.

Since the outbreak of the crisis, many Greeks have reduced their balances at domestic banks in order to hold them as cash or transfer them abroad or to foreign banks ("capital flight"). Possible motives include fear of taxation, the expectation of monetary reform or fear of insolvency of the bank holding the account or fear of a sovereign default. According to TARGET2 balances, capital flight from Greece accelerated in January 2015.

The high level of unemployment is also accompanied by many early retirements and, among other things, a loss of social security contributions due to unemployment. The pension funds have suffered considerable losses. As a result of low contributions, due to high unemployment and the poor economic situation for companies, pension funds were short at least 17 billion euros at the end of 2016. Since the beginning of the economic crisis, the number of farmers has increased by 40,000 within two years.

In June 2013, the IMF stated in a report on the first aid package that it should not have been disbursed at all because Greece met only one of four conditions in 2010. In addition, the troika's conditions had provided too little stimulus for growth and had instead further exacerbated the severe recession that was inevitable due to the country's over-indebtedness and lack of international competitiveness. IMF economist Blanchard conceded that the multiplier effect of the budget cuts had been stronger than initially assumed. Overall, however, fiscal consolidation had caused only a fraction of the recession. Other important causes, he said, were credit bubble-driven growth above Greece's growth potential in the years leading up to the crisis, the lack of or poor implementation of structural reforms, capital flight due to Grexit fears, low business confidence and unstable banks.

As a result of the social ills in the country caused by the financial crisis and further exacerbated by austerity measures, right-wing and populist parties have gained strong support.

In the refugee crisis since 2014, Greece was particularly hard hit due to its location as the first European country where refugees arrived. Greece was on a preferred refugee route through which refugees from Africa and Asia primarily arrived in Europe (alongside Spain, Italy and Malta). This created major financial, administrative and logistical challenges for the Greek state. This also had a serious impact on the state's pre-existing problems. Since a fence was erected on the border with northern Macedonia by the government there and with Austrian help, refugees have been piling up in Greece. An EU-wide distribution of refugees was initially not possible despite an agreement by EU heads of government. The transfer of financial aid and the deployment of officials to Greece were equally slow.

In September 2016, a meeting of the heads of government of the European Mediterranean countries suffering from the financial crisis was held in Athens at the invitation of the Greek prime minister. The leaders of France, Italy, Portugal, Malta, Spain (which sent a representative of the acting head of government) and Cyprus attended. According to Greek government circles, the economic future of Europe and the refugee crisis were discussed there.

Social consequences in Greece

The financial crisis and subsequent reforms have led to a deep social crisis in Greece. The recession that began during the financial crisis in 2008 deepened with the onset of the Greek debt crisis and continued into 2013. Compared to 2007, Greece's price-adjusted gross domestic product plummeted by 26 percent by 2013. Only in 2014 was there a slight recovery for the first time, with growth of 0.4 percent. Private assets have declined.

As part of the reforms, taxes were raised sharply and new taxes were introduced. Value-added tax, at 19 percent before the financial crisis, was raised to 24 percent, a figure in the upper third of rates within the EU.

Unemployment rose from 7.4 % in July 2008 to 27.2 % in January 2013, and many citizens are poor or at risk of poverty after repeated cuts in pensions and social services (abolition of the minimum wage, reduction in health care spending and spending on the unemployed). Infant mortality - comparable to the situation in other EU countries suffering from a financial crisis - has increased since the reforms were implemented. Many high achievers, including entire families, have left the country, which means that Greece is suffering from a talent exodus.

As of October 2016, the minimum wage has been reduced by 22% and salaries have fallen by an average of 24% as a result of labor market reforms. Protection against dismissal is to be relaxed.

One in three children in Greece is at risk of poverty; the proportion increased from 27.7 percent (2010) to 37.8 percent. The increase in the total number of children at risk of poverty since 2010 is the highest in the EU, while in second place is Cyprus, according to Eurostat.

Since the first bailout in 2010, the average income of pensioners has fallen from 1,200 euros to 833 euros per month by 2016. One in four Greeks over 65 is considered at risk of poverty. By comparison, around one in six new pensioners in Germany is currently at risk of poverty.

The financial crisis is also having an impact on the healthcare system. After pharmacists were no longer paid by the state health insurance funds for months, hundreds of thousands of insureds of the largest health insurance fund Eopyy have to pay for their medications in cash at pharmacies and then submit the receipt to the health insurance fund. For the chronically ill and the destitute, the obligation to pay some of the costs of medication themselves is jeopardizing medical care.

According to wastewater analyses, the use of psychotropic drugs in Athens (where about one-third of Greeks live) has increased 35-fold (neuroleptics) to 11-fold (antidepressants) since 2010, depending on the substance class studied. During the economic crisis, Greece's suicide rate increased, in some cases significantly. According to the Greek Ministry of Health, it nearly doubled between 2008 and 2011 and was 40 percent higher in the first five months of 2011 alone than in the same period a year earlier. According to the latest WHO survey of 2012, however, Greece still has the lowest rate of all eurozone countries. The suicide of 77-year-old pharmacist Dimitris Christoulas, who shot himself in Syntagma Square on April 4, 2012, caused a particular stir. In his suicide note, he wrote that he preferred to end his life with dignity before it became necessary to search the garbage cans for food, because his pension was no longer sufficient for him to live with dignity, and this despite the fact that he had paid into it for 35 years without any subsidies.

In addition to changes expected by the "institutions" in the right to strike and the trade unions, as well as in the pension system, privatization is also to be continued. After the EU Parliament spoke out against the privatization of the public water supply in a resolution in September 2015, saying that "water is not a commodity but a public good", the "institutions", which include the EU Commission, now expect the privatization of the Greek water supply. Similarly, the railroads, several airports, roads and other infrastructure are to be privatized. Half of the expected proceeds are earmarked for debt reduction. In the case of the privatization of the airports, the sale to Fraport met with massive criticism, as documents relating to the sale became known which not only deal with the sale but also prove that the Greek state is liable for losses incurred by the company despite the sale.

Financial consequences for creditors

The aid packages have fundamentally changed the creditor structure. While Greece was mainly indebted to banks and insurance companies before 2010, it became more and more a debtor of the euro countries in the years thereafter.

In July 2011, banks and investors had agreed to "voluntarily waive an average of 21 percent of their claims. While the Greek government urged them to agree to this voluntary waiver, the German government objected to these plans and demanded a larger debt waiver, which would have to be at least 50 to 60 percent. In the end, private creditors then waived 53.5 percent of their debts and also agreed to a lower interest rate on the newly issued bonds, so that they lost "more than 70 percent" of their money overall.

The situation was different for the state creditors: In the first aid package of May 2010, the IMF had granted 30 billion euros and the other euro countries 77 billion euros (of which Germany granted 15.17 billion euros) in aid loans. By the end of 2011, Greece had transferred 380 million euros in interest to Germany for loans that had fallen due.

In the second aid package from February/March 2012, Greece was lent a total of approximately 130 billion euros by the ECB and the EU.

As of February 2012, the ECB held Greek government bonds worth EUR 56.5 billion. When the investments mature, the ECB receives interest as well as repayment. As of June 2015, Greece is paying the repayment and interest originally agreed in the 2010 and 2012 aid packages for the loans it received from the IMF and the ECB. Interest rates on the ECB loans range from 2.3% to 6.5%. The repayment of principal and interest is scheduled for a period from 2012 to 2037. In March, May and August 2012, Greece transferred a total of around EUR 11.1 billion to the ECB for debt repayment. In 2012, an FTD article from March 2012 expected interest of 2.5 billion euros, and by 2037, 12.7 billion euros in interest gains were to be accumulated. The profits will be distributed to the euro countries proportionately according to the size of the ECB's capital providers. Accordingly, the largest ECB capital provider, the Deutsche Bundesbank, also receives the largest share of interest from the ECB. Low interest rates and long maturities do not reflect the credit default risk in line with the market.

Compared with the ECB loans, the borrowing countries have to pay lower interest rates for loans originating from the EFSF or the ESM. They consist of the EFSF borrowing fee and administrative costs (see also section Second EU and IMF rescue package - July 2011 to February / March 2012). The EFSF or ESM lenders changed the terms and conditions for Greece several times (see section #Measures by the EU, ECB and IMF). The loan maturity of the EFSF loans was increased by several decades and interest was deferred for 10 years.

In January 2015 Athens had liabilities of around 320 billion euros. Private creditors accounted for around 20% of this, or 64 billion euros. The major European commercial banks have sold most of their Greek bonds. "23.5 billion euros the German financial institutions currently still have lying there, much less than years ago."

Athex Composite Share Price Index 1974-2012

Unemployment trend in Greece since 2004

Price Development of a Greek Government Bond between January 2007 and August 2011

Demonstration in Patras 2011

International positions and actions on austerity and debt relief.

26 well-known economists, including Joseph Stiglitz and Thomas Piketty, positioned themselves against EU austerity in a public letter in 2015.

In October 2016, the IMF, led by Christine Lagarde, found that austerity and reform measures alone were not a solution to the crisis and called for a debt haircut for Greece.

Prime Minister Tsipras demanded in mid-2016 that the EU end austerity and provide an investment program for the states suffering from the crisis.

U.S. President Obama advocated debt relief during his visit to Greece in November 2016.

In November 2016, Portuguese Finance Minister Mário Centeno spoke out in favor of a debt haircut for Greece, saying that aid to consolidate Greece's public finances without the IMF would be acceptable to the EU.

EU Economic and Financial Affairs Commissioner Pierre Moscovici advocated debt relief in November 2016.

German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble currently rejected a second debt cut or debt relief for Greece at the end of November 2016.

On December 5, 2016, the finance ministers of the Eurogroup decided on several measures that will enable Greece to obtain further debt relief. After Prime Minister Tsipras decided in mid-December 2016 to help out needy pensioners with an additional one-off payment and at the same time lowered VAT on islands hit hard by the refugee crisis, the Eurogroup froze the previously agreed debt relief. The leader of the SPD MEPs, Udo Bullmann, expressed that Schäuble and Dijsselbloem wanted to use this to bring about a change of government in Greece. He said the Social Democrats in the European Parliament were "dismayed by the attempt of the EU lenders to influence the domestic policy of Greece and thus of a member of the Eurogroup"; the one-off payments to Greek pension recipients with particularly low incomes were fully financed. Here, he said, the aim was not to restore the economy to health, but to bring about a change of government. Tsipras spoke of "political blackmail.

On December 15, 2016, Pierre Moscovici, the commissioner in charge of the EU's economic, monetary, fiscal and customs union affairs, published an article in the Financial Times. He said that a debt cut for Greece was essential. Former Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis responded by accusing Moscovici of hypocrisy, saying Moscovici rejected further austerity but demanded economic growth of 3.5% per year for 10 years from Greece. A few weeks earlier, the ECB ruled out another aid package for Greece. As of December 2016, the Greek government is counting on being included in the ECB's bond-buying program, which in turn will allow it to raise money in the market in 2017. The IMF's decision on Greece's debt sustainability is expected in January, with the IMF already announcing in December that "austerity measures in Greece have gone too far and that the IMF does not expect austerity measures in the social sector."

See also

- International Financial Control in Greece 1898-1978

- Public debt of Greece

- ELSTAT

- Euro crisis

- Grexit

- London Debt Agreement

Questions and Answers

Q: What caused the Greek government-debt crisis?

A: The Greek government-debt crisis was caused by sudden reforms and austerity measures following the financial crisis of 2007–08.

Q: How did this affect people in Greece?

A: This made people in Greece poorer, as they lost money and land.

Q: How long has the recession been going on for?

A: The recession has been going on for longer than any other advanced capitalist economy to date, even longer than the US Great Depression.

Q: What is a trade deficit?

A: A trade deficit means that a country is buying more goods from other countries than it produces itself, so it must borrow money from others to finance its purchases.

Q: How did reports of Greek government disorganization influence borrowing costs?

A: Reports of Greek government disorganization increased borrowing costs, making it difficult for Greece to borrow money at an affordable cost to finance its deficits.

Search within the encyclopedia