Greco-Persian Wars

![]()

This article is about the classical Persian Wars. For the centuries-long conflict of the Roman or early Byzantine Empire with the Sassanids, see Roman-Persian Wars.

Persian Wars

Ark - Marathon - Thermopylae - Artemision - Salamis - Plataiai - Mykale - Eurymedon

The Persian Wars, or Persian Wars for short, is the term generally used to describe the attempts made in the early 5th century BC by the Persian Great Kings Darius I and Xerxes I to annex Greece to their empire by force. These ventures failed, however, despite formidable Persian superiority, when some 30 poleis, led by Athens and Sparta, decided to resist. The victorious Greeks soon elevated the successful but also self-sacrificing defense of their motherland to the status of a political myth, which was also expressed in plays such as The Persians by Aeschylus. This myth has survived in part into the 21st century and has often been interpreted historically as a supposed defence of the freedom of the Occident against "Oriental despotism and tyranny".

The Persian Wars were triggered by the so-called Ionian Revolt (500/499 to 494 BC). The highlights of the Persian Wars were the Battle of Marathon (490 BC) in the first Persian War, the naval battle of Salamis (480 BC) and the Battle of Plataiai (479 BC) in the second Persian War. The defeat of the Persians had far-reaching effects on further Persian, Greek and ultimately European history. The most important contemporary source for the events is the ancient historian Herodotus.

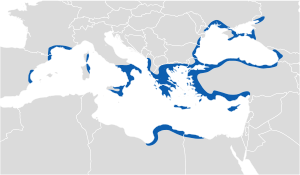

The Aegean during the Persian Wars

Initial Situation

Greece in the 6th century BC.

After the end of the Mycenaean palatial period at the beginning of the 12th century BC, parts of Greece had experienced an enormous decline in population and decline in material culture. Further decline occurred - even in regions spared from the upheavals around 1200 B.C. or those where there had been some after-bloom of Mycenaean culture in SH III C middle (second half of the 12th century B.C.) - during the 11th century B.C. From about the 8th century B.C. this process began to reverse. The population increased again, while influences from the Orient brought new art forms and also a new writing system. Even before this, the various Greek tribes had settled the islands of the Aegean and the western coast of Asia Minor. Due to the strong population growth and the resulting lack of land, the Greek colonization of the rest of the Mediterranean as well as the Black Sea area now began. At the same time, in the motherland and in the new colonies, the political organization based on the polis, the internally and externally autonomous city-state, emerged. Nevertheless, parts of the Greek population continued to be divided into tribal groups.

At the turn of the 6th century BC, the Greek poleis of Asia Minor came under the suzerainty of the Lydian Empire, while the European Greeks and the inhabitants of the colonies continued to remain independent. In the mother country, some larger poleis soon began to play a predominant political role. Sparta in particular, with its superior army, and Athens, which dominated economically, should be mentioned here. By the middle of the 6th century BC, Sparta had become the largest Greek polis in terms of area through numerous wars and had either subjugated most of the Peloponnesian peninsula or forced it into a system of alliances known as the Peloponnesian League. In Athens, the nobleman Peisistratos was able to establish a tyranny in the second half of the 6th century BC, similar to what had already happened in other Greek cities, and even passed it on to his sons Hippias and Hipparchus. In 510 BC, tyrannical rule was abolished by the Athenian aristocrat Kleisthenes, of the Alkmeonid family, and with the help of the Spartan king Cleomenes I. After Kleomenes tried to install Isagoras, a pro-Spartan politician, as archon in Athens, he was overthrown by Kleisthenes and his supporters, who then introduced democracy in Athens. The new political system was strong enough to repel a Spartan invasion to restore Isagoras to power, as well as attacks from Boeotia, Aegina, and Chalcis. Like Sparta and Athens, the other Greek poleis of the mother country were involved in constant conflict with each other and seemed hardly capable of common political action. The disruption of the Greek world even went so far as to cause various factions within the individual poleis to fight over power.

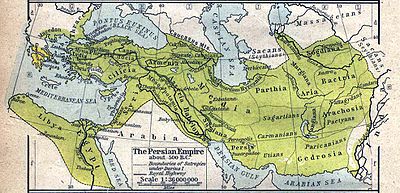

Persia in the 6th century BC.

In the middle of the 6th century BC, the world of states in the Near East, which had emerged after the end of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, underwent a profound transformation with the rise of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. This was triggered by the expansionist policies of the Persian king Cyrus II. who ruled over a small empire in southwestern Iran. Around 550 BC, he launched a war against the neighboring Iranian Medean Empire, which he eventually subjugated, so that he now abruptly commanded a territory that extended from Iran to eastern Asia Minor. Less than a decade later, Cyrus also brought Asia Minor under his rule with his victory over Kroisos, king of the Lydian Empire. Here the Persians came into contact for the first time with the Greeks settling on the western coast of Asia Minor, who had previously been under the sovereignty of the king of Lydia and who surrendered to the Persians after a brief resistance.

After some fighting in the east of the empire, the conqueror shortly thereafter turned south against the New Babylonian Empire, which stretched across Mesopotamia and the Levant. Disputes between the royal house there and the local priestly elite facilitated the conquest. After Cyrus had fallen in battle against Central Asian nomads, his son Cambyses II succeeded in conquering Egypt in the Battle of Pelusium around 525 BC, thus bringing the great phase of Persian expansion to a close, although smaller territorial acquisitions followed even later.

The death of Cambyses was followed by internal turmoil, and it fell to his successor Darius I, who was probably basically a usurper, to consolidate the young empire again. He achieved this through numerous reforms, such as the administrative and fiscal division of the empire into satrapies, the expansion of the transportation network, or the creation of new residences in Susa and Persepolis. His warlike undertakings included the conquest of parts of India and Thrace. The latter was related to the Persians' enduring struggle with the nomads of Central Asia and southern Russia. Darius crossed the Bosphorus into Europe in 513/512 B.C. with a ship's bridge to proceed against the Scythians north of the Danube. On his way north, he incorporated Thrace into the imperial federation and made the kingdom of Macedonia tributary. The struggle against the nomads was unsuccessful, but Darius had helped the Persian Empire to its greatest expansion by his campaign and made it a direct neighbour of the European Greeks. These now faced the greatest empire the world had seen up to that time.

The Persian Empire around 500 BC.

Greek settlement area in the middle of the 6th century BC.

The Ionian Revolt

→ Main article: Ionian Revolt

The Ionians formed one of the major Greek language groups. In the course of the shifts of peoples that Greece experienced during the Dark Ages, they had spread into Attica and over numerous islands and coastal areas of the Aegean. Among other places, they had also established themselves on the central part of the West Asia Minor coast (roughly from present-day İzmir in the north to north of Halicarnassus in the south). This area has since been known as Ionia. The cities that developed here formed the Ionian League in the early 8th century BC. Through the conquests of Cyrus, the Ionian Greeks in Asia Minor had also come under Persian suzerainty. Although the Persians endeavoured to grant the subjects a certain degree of internal autonomy, they also tried to secure their rule by installing tyrannical regimes loyal to them in the Poleis of Asia Minor. In the great Ionian metropolis of Miletus a certain Aristagoras exercised this position. About the year 500 B.C., however, the latter chose to fall away from his masters, to abandon his position as tyrant, and to place himself instead at the head of an anti-Persian revolt. Why he did so is quite unclear. Herodotus reports that Aristagoras was the leader of a failed expedition against the island of Naxos and then turned against the Persians so as not to be held accountable for the failure. It is also possible, however, that he joined a rebellion that was already in the offing, in order not to be promoted from office by it himself. The dissatisfaction of the rich Ionian trading cities with the Persian rule seems to have increased at that time due to economic problems.

Aristagoras first tried to gain support for his cause in the Greek motherland. With King Kleomenes I in Sparta he fell on deaf ears. The theater of war seemed too far away to the Spartans and the prospects too unpromising. Moreover, Sparta was about to start a war against its old arch-enemy Argos. In Athens Aristagoras had more luck. The government there was persuaded to assist the Ionians with twenty warships. Eretria on Euboea also sent five ships. All in all, the contribution of the European Greeks to the uprising was rather small, but nevertheless very momentous, as would later become apparent.

The revolt was initially quite successful. It apparently caught the Persian Empire unprepared. In 499 BC, the rebels succeeded in capturing and setting fire to Sardis, the ancient Lydian royal city and the most important Persian center in the west. Despite a defeat at Ephesus, the war spread to the Hellespont region and as far as Caria and Lycia. Even in Cyprus the Greeks now rose up. Then, however, the tide began to turn in favor of the Persians. Cyprus was reconquered, and the Greeks also had to withdraw from Sardis. In 494 BC, the Greek fleet was destroyed in the naval battle of Lade, and the revolt collapsed. The ships of Athens had withdrawn before, after a change of government at home. Aristagoras had also left Asia Minor early and fled to Thrace, where he died fighting locals in 497 BC. To make an example, the Persians destroyed Miletus, which was never again to occupy as important a position as it had before the revolt. Most of the cities, however, got off rather lightly. An attempt was made to pacify the region again, mainly by peaceful means. The land was re-surveyed and entered into cadastres, proper court hearings between members of different communities were made possible, and tyranny was also by no means reintroduced in all cities. The Persians also refrained from increasing tribute.

Questions and Answers

Q: What were the Greco-Persian Wars?

A: The Greco-Persian Wars were a series of wars fought between Classical Greece and Persia's Achaemenid Empire in the 5th century BC.

Q: How long did the struggle last?

A: The struggle lasted 50 years, from 499–449.

Q: Who wrote a history of the war?

A: Herodotus wrote a history of the war.

Q: When did Cyrus die in battle?

A: Cyrus died in battle about 530 BC.

Q: What was Aristagoras' role in the Ionian Revolt?

A: Aristagoras, the Tyrant of Miletus was on an expedition to conquer the island of Naxos with Persian support, but that was a failure. Before he could be dismissed, Arisagoras encouraged Ionia to rebel against the Persians which led to the Ionian Revolt.

Q: Who supported Aristagoras during this revolt?

A: Aristagoras got support from Athens and Eretria during this revolt.

Q: What action did they take together as part of this rebellion?

A: Together they burnt the Persian regional capital city, Sardis.

Search within the encyclopedia