Great Society

![]()

This article describes the social reform program. For the American band of the same name, see The Great Society.

The Great Society is the name given to an elaborate program of social policy reforms undertaken by the U.S. government under President Lyndon B. Johnson, who held office from 1963 to 1969. Johnson proclaimed it four months after assuming the presidency following the assassination of his predecessor, John F. Kennedy, in a speech at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor on May 22, 1964. In a series of speeches and messages to Congress, he elaborated on his concept in the months that followed. It continued until the end of Johnson's time in the White House in January 1969. The main goals of the reform program were to fight poverty, strengthen the rights of African Americans and other minorities, and make comprehensive reforms in the areas of education and health. Other aspects included environmental and consumer protection and the expansion of infrastructure.

The Great Society programs are strongly aligned with progressivism and can be seen as a continuation of the New Deal of the 1930s under President Roosevelt. The Great Society programs were favored in the 1960s by several factors such as the political leadership style of President Johnson and the great successes of his Democratic Party in the 1964 elections. During his tenure, about 96 percent of the Johnson administration's bills passed Congress, more than under any other president. Many of the legislative measures and resulting programs continue to have a significant impact on many aspects of life in the United States today.

President Johnson on his tour of poor neighborhoods in May 1964. .

Previous story

After the global economic crisis at the end of the 1920s, the Americans elected the democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt as their new president. Roosevelt, who initiated numerous social reforms in the 1930s under the slogan New Deal. These included the introduction of a Social Security Act and programs to combat poverty. As World War II began and the United States entered the war in 1941, foreign policy issues came into focus. Due to the noticeable recovery of the economy during the war years and the post-war boom, the signs of the economy were set for expansion anyway. After Roosevelt's death shortly before the end of the war in 1945, his successor in the office of President Harry S. Truman was anxious to continue socio-political reforms under the slogan Fair Deal (in reference to the New Deal). Truman also addressed the widespread problem of racial discrimination for the first time. By executive order, his directive to end racial segregation in the U.S. armed forces caused a sensation. Numerous African Americans were already benefiting in significant ways from New Deal programs. Truman's efforts to expand Social Security, among other things, were initially slowed by the 1946 midterm elections, however, as his Democrats lost their majority to the Republican Party in both chambers of the U.S. Congress. Truman was able to defend the presidency in 1948 against the Republican Thomas E. Dewey and again win the majority of seats in Congress, but his positions, which were regarded as liberal in the USA, were difficult to implement at the time, as conservative Democrats and many Republicans formed a "Conservative Coalition" against the reform ambitions of Truman, who remained in office until 1953.

After the moderate Republican Eisenhower administration, the Democrat John F. Kennedy took over the presidency in 1961, planning comprehensive social reforms under the title New Frontier. In particular, the poverty figures, which rose again after his inauguration, were to be reduced and the civil rights of colored people strengthened. While the Kennedy administration was able to set important accents in foreign policy during the Cold War, far-reaching domestic policy reforms were initially absent. In the summer of 1963, Kennedy spoke out in favor of nationwide desegregation. However, a parliamentary majority for this did not seem assured. Kennedy was unable to implement most of his domestic policy ambitions until the fall of 1963. In November 1963 he was assassinated in Dallas, Texas.

In accordance with the Constitution, his previous vice president, Lyndon B. Johnson, took over as president. Johnson, who unlike his predecessors had many years of experience in the legislative process, announced a decisive implementation of social reforms. In his New Year's address in January 1964, he announced the Great Society program, which he fleshed out in public speeches in the spring of 1964. In addition to the elimination of discrimination against African Americans, the war on poverty and programs to promote education were at the forefront.

Overview

Civil Rights

President Lyndon B. Johnson was a staunch opponent of racial discrimination and, after taking office, supported the Civil Rights Movement of African Americans led by the well-known civil rights activist Martin Luther King. Although people of color had been formally free and had civil rights since the end of the War of Secession in 1865, racial segregation, discrimination, and prejudice against dark-skinned Americans continued to prevail in the early 1960s. A desegregation bill proposed by President Kennedy seemed unlikely to pass Congress at the time of his death. Johnson supported its rapid passage and exerted considerable pressure with members of Congress, many of whom he knew personally. After the House of Representatives approved a bill, a filibuster (standing speeches) occurred in the Senate by senators who opposed it. Passage was then again called into question. President Johnson, on the other hand, took the position that the bill should be vigorously pursued, so that on his initiative the House ended the filibuster by voice vote. After lengthy deliberations, the bill passed the House of Congress and, after being signed by Johnson in a ceremony on July 2, 1964, became law. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 is considered the most significant U.S. federal law to equalize citizens of color and had lasting effects on many aspects of life. African Americans could now go to the same restaurants, swimming pools or shops, dark-skinned children could henceforth attend the same schools as whites.

When civil rights activists like Martin Luther King, who were in constant contact with the White House until 1966, called for the passage of a bill to strengthen voting rights for people of color, President Johnson initially stated in late 1964 that it would not be possible to follow up the 1964 Civil Rights Act with another one the following year. This would have to wait. As a result, there were numerous mostly peaceful rallies of colored people in the spring of 1965, especially in Southern cities. Johnson, however, had complied with the desire to protect these black protest marches with federal troops. After several demonstrations, Johnson finally changed his mind and declared in his March 1965 special session of Congress that a Voting Rights Act must be passed. A passage of the Voting Rights Act succeeded in the summer of 1965. The law, signed by Johnson on August 6, 1965, repealed racially discriminatory voting tests and led to a surge in the number of registered voters of African American descent. Southern states, where racial problems were most pronounced, saw particularly large increases in voters of color. What is less well known is that the Voting Rights Act applied not only to African Americans, but also to all other minorities. The Act also provides for the deployment of election observers to regions where discrimination is considered particularly likely.

The relationship between the president and leading figures of the civil rights movement such as Martin Luther King did not remain permanently positive. In foreign policy, the Vietnam War came more and more to the fore, against which a growing number of citizens turned. After initial hesitation, King increasingly criticized the president for his policies, which were aimed at preventing a communist takeover in the Southeast Asian country. Johnson always firmly rejected this and increasingly distanced himself from the civil rights activist. Although he did not change his basic position that African-Americans should be granted equal rights and opportunities, he increasingly regarded King's statements on foreign policy issues as a burden, so that King became de facto an undesirable person in the White House. After King's assassination in April 1968, the president nevertheless paid tribute to him as an important figure and called on people of color to condemn violent riots in King's image. Nevertheless, bitter riots broke out in many major U.S. cities in the weeks that followed. Shortly after King's death, Johnson again succeeded in passing significant civil rights legislation as part of the Great Society. The Civil Rights Act of 1968 was intended to make it easier for African Americans to find housing, expanding on the 1964 law. In addition to legislative initiatives, Johnson also used his executive powers as head of state and government by becoming the first U.S. president to fill high cabinet and Supreme Court positions with African Americans.

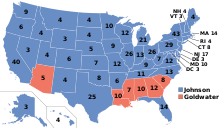

Elections 1964

When the 1964 presidential election came around again, the Great Society was Johnson's central domestic campaign issue. Johnson called for the expansion of the welfare state in many areas and the improvement of the living conditions of black people. Whereas in 1960 the Republicans had declared the more moderate Richard Nixon as their presidential candidate, who was only narrowly defeated by Kennedy, in 1964 the arch-conservative Senator Barry Goldwater from Arizona succeeded in securing the top candidacy. Goldwater stood for a massive dismantling of social and welfare programs; he was also known for his opposition to the president's racial policies. He called for leaving them to the states and also took an aggressive stance on foreign policy. The election on November 3, 1964, however, ended in a fiasco for Goldwater and his party: Johnson had defeated him with the largest popular vote in U.S. history, 61.1 percent (Goldwater scored 38.5 percent). Only some conservative southern states had voted for Goldwater, so that he had reached 52 votes in the electoral college, while Johnson had 486 there. Because of this sentiment against the Republican program, the Democratic Party was also able to expand its already clear majorities in Congress. In the Senate, 68 Democrats henceforth sat opposite 32 Republicans; in the House of Representatives, Johnson's Democrats won 295 seats, while the Republicans gained 140 mandates (→ see on this: Election to the United States Senate 1964 and Election to the United States House of Representatives 1964).

Johnson viewed the clear vote of the electorate as a clear mandate to further expand Great Society programs. His party's solid majorities in Congress made this expansion possible through the large number of liberal delegates who moved into the Capitol. Those "conservative coalitions" of Southern Democrats and Republicans who had blocked legislation under Truman and Kennedy could no longer maintain their policies because of the loss of power. The president now enjoyed broad support among many parliamentarians with a liberal worldview.

Poverty reduction and education

A central tenet of the Great Society was the war on poverty. Johnson proclaimed in his State of the Union Address in January 1964: "This administration declares here and now an unconditional war on poverty in America. Despite the thriving economy and growing prosperity in the United States, about 23 percent of U.S. citizens lived in poverty in 1963-64. For African Americans, that number was as high as 58 percent. Johnson succeeded in getting comprehensive legislation through Congress as late as 1964 aimed at reducing the poverty figures. The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 created anti-poverty programs at the local level. Legislative enactments of 1964 and 1965, in particular, established numerous programs that enabled children from poor families to attend preschool to improve their later opportunities in life. Other initiatives were aimed at promoting education (especially during and after school) among citizens who were considered poor. In the field of education, these included the creation of part-time classes with the aim of improving the quality of learning, as well as the provision of financial resources for teaching materials. In Johnson's and Congress's view, government initiatives should not only be designed to encourage the take-up of programmes, but in particular to enable the people concerned to "break out" of poverty themselves by providing a higher quality of education. This included various job preparation programs devoted primarily to young people. Other important initiatives were projects for the rehabilitation of slums and social housing.

The social programs to combat poverty quickly led to growing government spending. In 1964, one billion US dollars had already been allocated; by 1965, this sum had doubled. The number of citizens living in poverty fell from 23 to less than 13 percent within five years. For African Americans, that number dropped from 58 to 27 percent.

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, signed by Johnson on April 11, 1965, ended the federal government's longstanding taboo on providing additional funding for education (which is largely a state responsibility). The act provided about $1 billion for the expansion of educational facilities. This included, in particular, the expansion of learning opportunities in schools and the purchase of new teaching materials. A 1968 law also provided funding for various English language courses, mostly for immigrants. However, this program expired in 2002.

Health policy

On July 30, 1965, Johnson signed the Social Security Act of 1965 in Independence, Missouri, in the presence of former President Harry S. Truman. The newly introduced tax- and contribution-financed health protection included, on the one hand, Medicare, a public and federal health insurance predominantly for pensioners over the age of 65, and, on the other hand, Medicaid, financed only by federal, state and local taxes, a health insurance for particularly needy people, thus closing a central gap of the New Deal. President Truman had planned a similar law during his term, which Congress rejected.

Environment

Another consideration of the Great Society programs was an improvement in environmental protection. Despite the fact that environmental policy was a marginal issue in the 1960s, some laws of central importance were enacted as part of the program: for example, on the initiative of Johnson and his Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Lee Udall, Congress passed the Water Quality Act, a law designed to ensure the quality of water in the United States. The Clean Air Act of 1963 made air purity an authoritative aspect of industrial and energy policy for the first time. The Great Society laid the foundation for federal species protection, establishing four National Parks, six National Monuments, eight National Seashores and Lakeshores, nine National Recreation Areas, and 20 National Historic Sites, and dedicating 56 National Wildlife Refuges of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. On October 2, 1968, Johnson signed into law the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which provided for the protection of rivers as well as the reintroduction of wildlife near rivers.

Consumer protection

The issue of consumer protection was also addressed as part of Great Society social reform, with government quality standards introduced for many products such as meat through the Wolesome Meat Act of 1967. Further quality standards were enacted for electronics and clothing.

Gun Control

Under the impression of the deadly assassinations of the civil rights activist Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy in April and June 1968, the Johnson administration sought to tighten gun laws. After long deliberations in Congress, the Gun Control Act was passed in October 1968. Among other things, this provided for a ban on fully automatic firearms and the illegalization of private mailing of guns. The President signed it on October 22, 1968, but spoke of the need for further action. Since two major rampages in the USA in 2012 and the efforts of President Obama's administration to take further action at the federal level, gun rights and the Great Society measures of the 1960s have once again become the subject of increased attention in the US public.

Congressional elections 1966

After numerous Great Society programs had been launched in the 88th and 89th Congresses (1963 to 1965 and 1965 to 1967) by the end of 1966, Johnson had to accept a setback for his government program in the 1966 midterm elections. While the Democrats had lost only three seats in the Senate in the November 1966 elections (instead of 67 they now had 64 of 100 seats), the Republican Party gained 47 seats in the House of Representatives. While the president's party was still clearly in the majority, the result reflected growing popular dissatisfaction with foreign policy developments such as the Vietnam War, which was causing a growing polarization in U.S. society. While the 1966 election did not spell the end of the Great Society, a slowdown was noticeable in 1967 after the newly elected Congress convened in January. Due to the rising costs of the military involvement in Vietnam, spending increases also had to be slowed.

Final phase in the Johnson administration

The year 1968, on the other hand, despite the tense foreign policy situation and under the impression of a polarized society in the USA, once again led to a "wave" of important legislation within the framework of the program. President Johnson had declared his renunciation of a further term of office on 31 March 1968, leaving office on 20 January 1969. He was succeeded by Republican Richard Nixon, who won a close election against Johnson's Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey.

Johnson signs the Social Security Act of 1965, with former President Harry S. Truman on the right.

Signing of the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964

President Johnson during his tour of poor neighborhoods, here in Knoxville in May 1964.

Result of the 1964 presidential election by state

President Johnson signing the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 is signed by President Johnson in July 1964.

March of the Civil Rights Movement in Alabama in the spring of 1965.

Search within the encyclopedia