Great Pyramid of Giza

The Pyramid of Cheops is the oldest and largest of the three pyramids of Giza and is therefore also called the "Great Pyramid". The tallest pyramid in the world was built as a tomb for the Egyptian king (pharaoh) Cheops (ancient Egyptian Chufu), who ruled during the 4th Dynasty in the Old Kingdom (about 2620 to 2580 BC). Together with the neighboring pyramids of the pharaohs Khafre and Mykerinos, it is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World that has survived to the present day. Cheops did not choose the royal necropolis of Dahshur as the building site, like his predecessor Snofru, but the Giza plateau.

In ancient Egypt, the pyramid complex was called Achet Chufu ("Horizon of Cheops"). Its original side length is calculated at 230.33 m and the height at 146.59 m (about 280 cubits). Thus, it was the tallest structure in the world for about four thousand years. Since it was used as a quarry in later times, its height is still 138.75 m today. Its measurement was made to a very high degree of accuracy, which has not been equalled in subsequent buildings. It is exactly aligned with the four points of the compass, and the difference in the lengths of its four sides is less than one part per thousand. The building material was chiefly locally occurring limestone. Granite was used for some chambers. The facing of the pyramid was originally made of white Tura limestone, which was almost completely removed in the Middle Ages.

On the north side there is the original entrance and inside a chamber system consisting of three main chambers: the rock chamber in the grown rock, the so-called queen chamber a little higher in the core masonry and the so-called king chamber above the large gallery with the sarcophagus in which the king was presumably buried. No body or grave goods were found. The pyramid was obviously plundered in the Middle Ages at the latest, probably already in Pharaonic times. The function of the individual chamber systems in the Cheops pyramid is unclear in many respects. The spatial program probably reflects religious ideas, such as the idea of the ascension of the dead king to heaven: initially to the imperishable stars of the northern sky, then to the land of light, the realms of Re in the sky.

On the east side of the pyramid is the mortuary temple, of which only the foundations remain today. Almost nothing has been preserved of the way up and the valley temple. In the adjacent eastern cemetery the nearer relatives of Cheops were buried. Among them are several large mastabas mainly for his sons and their wives as well as three queen pyramids whose assignment to individual queens and princesses cannot be made without doubt so far. A fourth, smaller pyramid served as a cult pyramid for the king. In the west a cemetery of smaller mastabas was built, mainly for high officials. Seven boat pits were discovered in the vicinity of the Pyramid of Khufu, two of them still intact and sealed. The king's barque, disassembled into 1224 individual parts, has been restored and reassembled and has been on display in the Boat Museum since 1982. The significance of the king's boats is still unclear. Perhaps they are connected with burial or with certain ideas of the afterlife.

Ancient historians already dealt with the Cheops pyramid, especially Herodotus, who lived more than 2,000 years after the construction of the pyramids, drew his information partly from dubious sources and wrote from the perspective of a Greek. It was with him that the confusion about the pyramid, which continues to this day, began. From the 15th century it was the destination of European travellers and from the 18th century of research expeditions. At the latest, the investigations of Flinders Petrie, founder of modern Egyptian archaeology, refuted numerous mythical ideas. In more recent times, especially the shafts of the Queen's Chamber were the subject of investigations.

Of particular interest for the logistics of the construction of the Cheops pyramid are papyrus fragments that were discovered in Wadi al-Garf in 2013. Among them was a logbook of an inspector named Merer, who led a work crew that shipped stones from the Tura quarry to Giza for the construction of the Cheops pyramid (Papyrus Jarf A and B). These papyrus finds provide for the first time an "inside" picture of the administration of the early Old Kingdom.

The Pyramid of Khufu, together with many other pyramids, has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1979 as part of the complex "Memphis and its City of the Dead - the Pyramid Fields from Giza to Dahshur".

The pyramid

The Giza Plateau

King Snofru, presumably father and predecessor of Cheops, had a total of three large pyramid complexes built: the Meidum Pyramid in Meidum, the Bent Pyramid and the Red Pyramid in Dahshur. With the latter, a geometrically true pyramid was achieved for the first time, and the development from the brick mastabas to the stepped pyramids of the 3rd Dynasty came to an end. Cheops chose a new building site, the "Giza Plateau", for his building project. Presumably, he left the royal necropolis in Dahshur because it no longer offered sufficient space for a large pyramid complex, because there was not enough limestone available and perhaps because he feared the unstable subsoil of clay slate. In contrast, the saddle-shaped rock plateau, the so-called Mukattam formation, at Giza was characterized by a firm, compact subsoil and possessed the necessary geological consistency. At the time of Cheops, there were already a number of private tombs there of obviously influential officials from the first three dynasties. The northeast edge of the Mokattam Formation was chosen as the building site, where a large compact rock mound rose. Michael Haase assumes that such rock bases, on which also the Djedefre Pyramid and the Khafre Pyramid were erected, were a decisive criterion for the choice of location. Beside a saving of work this could also have been motivated by static problems during the construction of the kink pyramid. The rock core emerges clearly in a total of five places:

- After a descending section of 33 m, the descending corridor is a gallery carved out of the rock, from a height of 3 m above the base of the pyramid to the level of the base level.

- The air/escape shaft also penetrates the rock core from the base level to a height of 7 m above.

- At the northwest corner of the core wall, the rock clearly extends northward and southward.

- At the northeast corner, the rock outcrops to a height of 1.95 m above base level. It was adapted to the shape of the superstructure by working it down in terraces or filling it with layers of stone to optimally fit the outer facing stones.

- On the south side, near the southeast corner, the core appears at least two steps high.

The volume of the rock core is estimated at 7.7% of the total volume of the Cheops pyramid.

Levelling and calibration

First, the base surface was leveled by making a level plateau around the rock core, on which the base of the pyramid was measured. On the one hand, the rock core was removed for this purpose, and on the other hand, the cracks were filled with well-paved blocks. A foundation base of Tura limestone was laid on the levelled rock near the pyramid core. This was used to accurately measure the edge lines, construct the right angle, and ultimately lay the first course of stone. The levelling of the foundation is very precise: The largest difference in height is only 21 mm.

The measurement of the pyramid was the task of the Harpedonapts. It also shows an admirable accuracy, which was already not reached or striven for in the following constructions. This is all the more astonishing in view of the elevated rock core, which made an exact measurement of the diagonals impossible. The pyramid is basically exactly aligned with the four cardinal points, for the azimuth, the deviation from the north direction, amounts to only 3′ 6″ to the west. The four sides deviate very little from the intended length of 440 cubits (≈ 230.383 m), by 7 cm on the south side and 13 cm on the north. An even greater accuracy is found in the measurement of the right angle at the corners. The deviation is 2″ at the northwest corner, 3′ 2″ at the northeast corner, 3′ 33″ at the southeast corner, and 33″ at the southwest corner. The angle of repose was 51° 50′ 40″, which, according to ancient Egyptian measurement, gives a setback of five and a half handbreadths (5 hands plus 2 fingers is 5.5 seced) to 1 cubit in height. From this an original height of 280 cubits (= 146.59 m) can be deduced. Today the pyramid is still 138.75 m high.

Today's outer surfaces of the pyramid are curved inwards and are not flat. On the north side, the inward curvature is 0.94 m.

Core masonry and cladding

Originally, the Pyramid of Khufu was faced with polished Tura limestone. However, many of these stones were broken out and later reused for the construction of buildings in Cairo. As a result, the outer faces are no longer smooth, but step-like. The cladding is only partially preserved in the lowest layers. On these still preserved blocks markings from the quarry work could be detected, which had been applied with red paint. The top of the facing was the pyramidion (no longer preserved). This was probably the only element of the facing that was not made of Tura limestone, but of basalt or granite.

The core masonry consists of blocks of nummulitic limestone. The blocks on the outside of the core masonry are arranged horizontally. Their height is one to one and a half meters. Today only 203 layers are preserved, the top seven have probably been broken out. The weight of the blocks is estimated at one (in the uppermost layers) to three tons (in the lowermost layers). For the construction of the King's Chamber, however, blocks of rose granite weighing forty to seventy tons had to be transported to a height of about 70 meters.

Between the outermost layer of the core masonry and the limestone cladding, a further layer of mortar and so-called "backing stones" was inserted. These are small stones that increased the adhesion of the two types of masonry, which were different in terms of material and construction. Georges Goyon discovered a quarry inscription on a backing stone of the 4th stone course on the west side. As with the inscriptions in the relief chambers, this is upside down and in cursive script. Leslie Grinsell located other inscriptions and marks in ochre and sometimes black paint on what are now exposed "backing stones" of the 5th and 6th stone courses. These are measurement lines, names of workers' troops and in two cases the name of Cheops.

The mortar used in the construction of the core is very hard and usually of a pale pink colour. It is composed of various elements such as gypsum, sand, powdered granite and limestone. The joints are less than half a millimetre wide on the outer sides and were filled with a semi-liquid gypsum mortar. On the undersides, the cladding blocks have lifting holes. Through these, the blocks could be pushed in sideways with levers. The lever holes were also closed with mortar and patching stones after the blocks had been moved. Investigations by French geophysicists have shown that the structure of the core masonry is probably very uneven. It probably contains spaces filled with sand, fine gravel and other waste material from the site. This method saved material, effectively shifted the pressure in the pyramid, and probably had a beneficial effect during earthquakes.

Quarry inscription on a "Backing Stone" with the name of Cheops after Georges Goyon.

Blocks of the outside of the core masonry

Corner of the Khafre pyramid, where the massive rock core can be seen, over which the pyramid was built.

Bottom layer of the original limestone cladding

The construction of the pyramid

See also: Section "Stone Construction" in: Building Techniques in Ancient Egypt and Theories on Stone Transport in the Construction of the Egyptian Pyramids

Quarries and stone working

Most of the stone for the construction of the pyramid was quarried on site. Most of the material for the core masonry came from the main quarry area about 300 m south of the tomb. Today, the quarry is a huge, horseshoe-shaped plateau void that lies up to 30 m below the original surface. A petrographic analysis of rock samples has shown that stone material also came from a quarry area on the break-off edge east of the pyramid, from a quarry area in the southeastern area of the plateau, and a small amount from an undetermined quarry area. Valuable clues to the ancient quarrying techniques are provided by the triangular rock area between the main quarry of Cheops and the Sphinx. Here the rock was not quarried as thoroughly as in the main quarry, which is why blocks left standing by the quarrymen are still recognizable. Rock rectangles the size of small houses, separating corridors so wide that whole groups of tourists can march through them today, are divided by narrower gullies that were just wide enough for a worker picking his way to stand in. In some places the blocks have remained almost detached from the rock.

The surviving copper tools, machining marks on the stone surfaces, unfinished monuments and tests on the hardness of copper tools have shown that Egyptian stonemasons could work softer rocks with copper tools, but harder ones only with stone tools. The two groups divide between limestone, sandstone and alabaster on the one hand and granite, quartzite and basalt on the other. In addition to the numerous copper tools that archaeologists found, small fragments of corroded copper were detected in the cover blocks of the southern boat pits, which appear to be broken edges of the copper tools. To smooth the pyramid mantle of finest Tura limestone, only chisels about 8 mm wide were used. The granite blocks, on the other hand, were worked with pear-shaped dolerite mallets weighing 4-7 kg, but these became rounder the more often the stonemason used them. Smaller stones, sometimes clamped between two wooden sticks, were used for the fine work.

The granite had to be worked with a material at least as hard as quartz, the hardest of the minerals of which it is composed. For the external shaping of the slabs and the granite sarcophagus, therefore, copper saws and copper drills were used in conjunction with a grinding mixture of water, gypsum and quartz sand. The copper only served as a guide, the quartz sand did the actual cutting. Dried remains of the mixture, which was coloured green by the copper, can still be seen in the incisions on the blocks of the temple of the dead. The sarcophagus was hollowed out using tubular drills made of copper, as known from various representations from the Old Kingdom.

·

Stone carving after a representation in the tomb of Rechmire (TT100) from the New Kingdom.

·

Use of a tubular drill

·

Copper tools found in Giza

Construction ramps

The type of ramp that was necessary for the construction of the Pyramid of Khufu has been the subject of countless studies. However, many do not take into account that for this pyramid in particular there is little evidence from which to reconstruct a clear picture of the type of ramps used, but that such ramps are well attested from several other pyramids. These remains show that the Egyptians did not use the same ramp system for every pyramid. Just as there was no standard pyramid, there was no standard method for building a pyramid, and it is precisely the largest ones that also offer the greatest variation in terms of construction methods.

The following ramps, among others, are attested from the 3rd and early 4th dynasties:

- At the unfinished Sechemchet pyramid in Sakkara a ramp leads from the quarries west of the pyramid perpendicularly over the huge enclosing wall up to the first step of the pyramid.

- With the pyramid of Sinki, Günter Dreyer and Nabil Swelim discovered, as it were, a snapshot of the construction of a small stepped pyramid, with four ramps leading from all sides towards the pyramid.

- At the Meidum pyramid remains of a grinding track or possibly ramp have been preserved, which apparently led directly over the subsidiary pyramid from the southwest and projected onto the higher pyramid levels on the west side, and another ramp comes from the east.

- At the Red Pyramid of Dahshur there are remains of two construction ramps of compact stone chips and marl, which come very close to the pyramid from the quarries to the southwest. From the east come two more ramps of white limestone chips, over which perhaps the facing stones were brought.

Near the Pyramid of Khufu, a huge ramp was excavated leading from the quarries west of the Sphinx onto the pyramid plateau, to the east of the Queen's Pyramids. The ramp, carefully constructed of read stones, is 5.4 to 5.7 m wide, contained two parallel courses of masonry, and was coated with mortar. The ramp survives for a length of 80m. The fill, which has been removed today, contained seal impressions with the name Cheops. Probably, the ramp served for the delivery of the rocks to the plateau, possibly not for the pyramids, but for a mastaba of the late 4th Dynasty (Mastaba G 5230).

Mark Lehner suggested that the rock excavation northwest of the Pyramid of Khufu might indicate the position of the main ramp leading up from the quarries to the pyramid ramp proper, the foot of which he assumed to be in this corner of the pyramid. The position and shape of this ramp were the starting point of some recent theories on the construction of the pyramid. For Dieter Arnold, however, all these theories remain in vain, since no traces of actual pyramid ramps have survived.

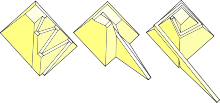

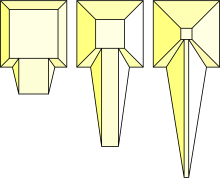

The question of the shape of the ramp gave rise to a wide variety of reconstruction attempts. Perhaps a combination of different shapes was also used:

- The straight or perpendicular ramp: Many researchers assume a straight ascending ramp on one side of the pyramid. It is disputed whether it covered the side surface completely or only partially.

- The zigzag ramp: According to this theory, the ramp should have zigzagged up one side of the pyramid.

- The spiral ramp: According to this idea, the ramp spiraled up around the pyramid. Dows Dunham, for example, proposed that a total of four ramps, each starting at a corner, wound their way up the stepped, non-switched layers in a counterclockwise direction.

- The inner ramp: Dieter Arnold suggested this model, which, in contrast to the straight ramp, did not start so far outside, because part of the ascent would have been in the pyramid masonry itself.

Rainer Stadelmann assumes a ramp from the quarry to a corner, which then leaned against one side for the middle section of the pyramid. Via a multitude of small ramps the material was brought up onto the truncated pyramid from all four sides until a height of about 15 to 20 m was reached. Above a certain height these ramps could no longer be raised without the angle of inclination becoming too steep and the ramps too narrow. For this reason, Stadelmann proposes a variant here that the architect Nairi Hampgian has worked out: she allows the core building to grow upwards in a step or cube shape. While the four corners were already lined with cladding blocks, flanking ramps in the middle were still used for transport until space became too tight here too. The remaining stones were transported up the steps of the cube building by means of levers or pulley-like devices. After the pyramidion was brought up and the corners filled in, the last steps were filled in.

In the so-called NOVA experiment, Mark Lehner, the stonemason Roger Hopkins and a group of Egyptian masons attempted to test various theories on pyramid construction in practice by building a small pyramid near the Giza plateau. In the process, Lehner had the idea that ramps leaned against the outer surface: "Shuttering stones could serve as the foundation of an earthen embankment, complete with construction road, which were allowed to protrude further (singly or in layers)." Recent research by Zahi Hawass seems to support this theory: At the foot of the Queen's Pyramids, he was able to detect left-behind casing stones not decorated with bosses, which were in fact a block projection.

Port facilities

Rocks from the distant quarries and other materials and supplies were supplied via a large port area. At that time, the Nile probably ran two to three kilometres further west than it does today, and so a port could be connected to the Nile via one or more canals.

A harbor was located at the village of Nazlet el-Sissi, directly in front of the Valley Temple. In 1993, remains of walls could be found about 550 meters to the east, which indicate the eastern boundary of a flood basin or quay walls of a more extensive harbor complex. Thus, this harbor may have played a role not only in the context of the royal burial as a landing place and for the later supply of the cult of the sacrifice of the dead, but may also have been part of the infrastructure during the construction of the pyramid.

Another port may have been located east of the Giza Plateau, at the entrance to the central wadi. Investigations of the site confirm its existence, but an exact dating has not yet been possible. Logistically, the port would have provided a good connection to the quarries and their workplaces.

Workers' settlements

Since 1988 Mark Lehner has been excavating a workers' settlement south of the so-called Crow's Wall and Zahi Hawass an associated cemetery site. Although an unambiguous dating has so far only been possible to the reigns of Chephren and Mykerinos, it is assumed "that the settlement was already laid out under Cheops in the course of the erection of his tomb and was further used by the later royal builders on the Giza plateau."

Today the excavation area amounts to 40,000 m², but the settlement extends even further to the south. The settlement consists of gallery-like, north-south oriented complexes built of mud bricks, which were planned according to symmetrical specifications and partly separated from each other by roads. These run from east to west and divide the settlement into sectors. So far, various bakeries and production sites for copper, beer and fish have been identified, as well as administrative buildings. Furthermore, magazines and residential buildings could be located, including a purely residential area for the craftsmen and workers.

Traces of another workers' settlement, clearly dating to the reign of Cheops, were discovered between 1971 and 1975 south of the ascent of the Mykerinos pyramid. Enormous amounts of settlement debris, architectural parts of dwellings, seal impressions with the names of Cheops and Khafre, and pottery fragments of household furnishings from the early 4th Dynasty were found. The settlement was obviously removed with the construction of the Mykerinos pyramid and filled up at the site.

Further workshops are assumed to be located west of the quarries (near the Pyramid of Khafre), west and east of the actual construction site and in the vicinity of the harbour and the Valley Temple.

Hemiunu, the builder

Master builder of the Pyramid of Khufu was probably Hemiunu. He was a son of the construction supervisor Nefermaat, who led the construction of the Meidum pyramid under Snofru. Since Nefermaat was a brother of Cheops, Hemiunu belonged as a nephew to the extended family circle of Cheops. He held the office of the vizier and had also the title "overseer of all building works of the king". Thus, he supervised all construction work on the necropolis of Khufu.

Hemiunu's own tomb was Mastaba G 4000 in the West Cemetery. Excavators discovered a life-size seated statue of the tomb's owner in the statue chamber in 1912. It is the only known statue of this kind from a private person from the time of Cheops.

Papyri from Wadi al-Garf

→ Main article: Papyrus Jarf A and B

Of particular interest for the logistics of the construction of the Pyramid of Cheops are papyrus fragments discovered in 2013 in Wadi al-Garf, a port used in the 4th Dynasty for shipping traffic with the Sinai Peninsula. Among them was a logbook belonging to an inspector named Merer, who headed a work party that shipped stones from the Tura quarry to Giza for the construction of the Pyramid of Cheops. Presumably, the logbook was kept by the work party itself so that it could report to the administration on its activities. Other papyri recorded daily or monthly food deliveries for the work troops and are not least comparable to the Abusir papyri from the time of Neferirkare and Raneferef (5th Dynasty). These papyrus finds provide for the first time an "internal" picture of the administration of the early Old Kingdom. The port complex at Wadi al-Garf appears to be closely associated with the construction of the Pyramid of Khufu. It may even have been built for the purpose of bringing in copper from the Gulf of Suez, which was necessary for the tools used in pyramid construction.

From left to right: zigzag ramp (according to Hölscher), inner ramp (according to Arnold) and spiral ramp (according to Lehner).

Statue of Hemiunu in the Roemer- und Pelizaeus-Museum Hildesheim

Quarries near the Chephren Pyramid

Examples of straight ramps.

Search within the encyclopedia