Great Depression

![]()

This article is about the historically most significant Great Depression of the 1920s/1930s; for other meanings, see Great Depression (disambiguation).

The world economic crisis at the end of the 1920s and in the course of the 1930s began with the New York stock market crash in October 1929. The main features of the crisis included a sharp decline in industrial production, world trade, international financial flows, a deflationary spiral, debt deflation, banking crises, the insolvency of many companies and mass unemployment, which caused social misery and political crises. The Great Depression led to a sharp decline in overall economic performance worldwide, the onset of which varied in timing and intensity according to the specific economic conditions of individual countries. The world economic crisis lasted for different lengths of time in the individual countries and had not yet been overcome in all of them at the beginning of the Second World War.

National Socialist Germany had overcome the world economic crisis in 1936 in important respects and was one of the first countries to achieve full employment again. However, developments in Germany were also marked by job creation measures with poor working conditions as well as generally low wages, which were frozen at the 1932 level, and the introduction of compulsory military service in March 1935. In addition, full employment was contrasted with a massive misallocation of resources and ultimately the catastrophe of World War II, which Germany precipitated in 1939. In the United States, President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave the nation new hope with the economic and social reforms of the New Deal. Unlike the German Reich and many other countries, democracy in the United States was preserved during the Great Depression. The desolate state of the economy was overcome, but full employment was not achieved until 1941 with the arms boom after the United States entered World War II.

Modern scientific explanations of the causes and conditions of the world economic crisis include the analyses of Keynesianism and monetarism. More recent extensions to these explanations have been developed. There is a scholarly consensus that the initial recession of 1929 would not have become a world economic crisis if the central banks had prevented the contraction of the money supply and alleviated the banking crises by providing liquidity. The main contributors to the global spread of the economic crisis were the international export of crises through the then existing currency regime of the gold standard and the protectionism that set in during the Great Depression.

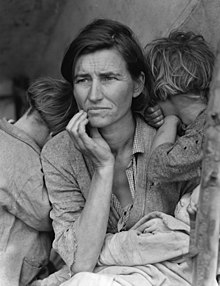

The crisis plunged many families into bitter hardship: migrant worker Florence Owens Thompson, California 1936 (Photographer: Dorothea Lange) .

Scientific explanations

There is a consensus among historians and economists that the initial recession of 1929 would not have become a Great Depression if the Federal Reserve had prevented the contraction of the money supply and eased the banking crisis by providing liquidity. This critique, elaborated in detail by Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz in A Monetary History of the United States (1963), had already been formulated in essence by John Maynard Keynes. The contemporary attempts at explanation that recommended the opposite are consequently discredited.

The Milton Friedman/Anna J. Schwartz thesis that the Great Depression was primarily a monetary crisis caused by a contraction of the money supply as a result of the banking crisis was supported in principle by 48% of the participating economists and by 34% of the participating historians in a 1995 survey. The opposite thesis of John Maynard Keynes, that a decline in demand, in particular through a decline in investment, caused the Great Depression and that the banking crisis was merely a consequence of it, was supported in principle by 61% of the economists and 51% of the historians in the same survey.

Peter Temin's thesis that a purely monetary explanation was artificial because the demand for money fell more sharply than the supply of money in the early years of the crisis was agreed to by 60% of economists and 69% of historians. More recently, there have been extensions of the Friedman/Schwartz monetarist explanation of the crisis to include non-monetary effects, which aim to better fit the empirical evidence and have met with a very positive response in the academic community.

Some countries did not experience a pronounced banking crisis, but were nevertheless hit by deflation, a sharp decline in industrial production and a sharp rise in unemployment. To these countries, the monetarist explanation is not readily applicable. However, historians and economists are almost unanimous that in these countries the gold standard acted as a transmission mechanism that transmitted the American (and German) deflation and economic crisis to the whole world by forcing (also) the governments and central banks of other countries to adopt deflationary policies. Furthermore, there is consensus that the protectionist trade policies brought about by the crisis made the global economic crisis even worse.

Contemporary attempts at explanation

The contemporary crisis interpretations of the Austrian School, Joseph Schumpeter, and the underconsumption theory have had no support in the mainstream of economists and historians since the mid-1930s. The theory that income inequality was a major cause of the crisis has been highly influential on some architects of the New Deal. It tends to be supported by historians; at least at present, there is no consensus for it in the mainstream of economics.

Joseph Schumpeter

Joseph Schumpeter saw the Great Depression as a historical accident in which three business cycles, the long-run Kondratiev cycle of technical innovation, the medium-run Juglar cycle, and the short-run Kitchin cycle, bottomed out simultaneously in 1929. Schumpeter was a proponent of the liquidation thesis.

Austrian School

In contrast to the later Keynesian and monetarist explanations, economists of the Austrian School saw the expansion of the money supply in the 1920s as the cause, from which a misallocation of capital had resulted. The recession, therefore, had to be endured as an unavoidable consequence of the negative effects of the wrong expansion in the 1920s. Government intervention of any kind was thought to be wrong because it would only prolong and deepen the depression. The monetary overinvestment theory was the dominant idea in the period around 1929. The American president Herbert Hoover, who largely followed this theory during the Great Depression, later complained bitterly about these recommendations in his memoirs.

Friedrich Hayek had criticized the FED and the Bank of England in the 1930s for not pursuing an even more contractionary monetary policy. While economists such as Milton Friedman and J. Bradford DeLong rank the representatives of the Austrian School among the most prominent advocates of the liquidation thesis and assume that they influenced or supported the policies of President Hoover and the Federal Reserve in the sense of non-interventionism, the representative of the Austrian School Lawrence H. White holds that the Federal Reserve's passivity cannot be attributed to the overinvestment theory. He objects that overinvestment theory did not call for contractionary monetary policy. Hayek's call for even more contractionary monetary policy was not specifically related to overinvestment theory, he argues, but to his hope at the time that deflation would break wage rigidity. From the 1970s onwards, Hayek also sharply criticised the contractionary monetary policy of the early 1930s and the mistake of not providing liquidity to the banks during the crisis.

Underconsumption theory and income inequality

In the industrial sector, productivity increased very strongly through the transition to mass production (Fordism) and through new management methods (e.g. Taylorism). In the Golden 1920s (mainly US due to balance of payments surplus as a creditor from World War I) there was a rapid expansion of the consumer goods and capital goods industries. Since corporate profits were rising much faster than wages and at the same time credit conditions were very favorable, there was a seemingly favorable investment climate that led to overproduction. Then, in 1929, there was a collapse in demand (which was already too low) and an extreme deterioration in credit conditions.

As in industry, productivity in agriculture had increased dramatically. The reasons for this were the increased use of machinery (tractors, etc.) and increased use of modern fertilizers and insecticides. This led to the fact that already in the 1920s the prices for agricultural products fell continuously. The Great Depression further reduced demand, so that by 1933 the market for agricultural products had almost collapsed. In the United States, for example, wheat fields rotted in Montana because the cost of harvesting was higher than the price of wheat. In Oregon, sheep were slaughtered and left as food for buzzards because the price of meat no longer covered the cost of transportation.

Some economists, such as Rexford Tugwell, Adolf Augustus Berle, John Kenneth Galbraith and others, see one cause of the crisis primarily in the pronounced concentration of income. They justify this with the fact that the highest-income 5% of the American population had almost one third of the total income in 1929. As a result of more and more income being concentrated in a few households, less was spent on consumption and more and more money went into "speculative" investments. This had made the economy more susceptible to crises.

Modern explanations

John Maynard Keynes

Theory

→ Main article: Keynesianism

In his Tract on Monetary Reform (1923), John Maynard Keynes had noted that fluctuations in the money supply can have distributional effects because some prices, such as wages and rents, are "stickier" (less flexible) than others. Because of this, in the short run, there can be an imbalance between supply and demand, which has a negative impact on economic growth and employment. During the Great Depression, it was actually observed that wages fell less than prices. Compensating through wage cuts was too risky a solution for Keynes, as companies would prefer to keep the money they saved liquid rather than invest it during an economic crisis. In this case, wage cuts would only lead to a reduction in demand. To restore the equilibrium between supply and demand, he recommended instead a corresponding expansion of the money supply.

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) explained the length and severity of the depression by the fact that investment decisions depend not only on the cost of financing (interest rate) but also on positive business expectations. Accordingly, a situation can occur where business owners are so pessimistic that they will not invest even if interest rates are extremely low (investment trap). Thus, firms would employ only as many people as needed to produce the quantity of goods expected to be sold. Contrary to neoclassical theories, a market equilibrium can thus settle below the full employment level (equilibrium under underemployment). This is the Keynesian explanation for the only slowly declining unemployment after the end of the recession phase (lasting from 1929 to 1933) until the end of the 1930s. In this situation of extremely pessimistic business expectations, monetary policy alone could not revive the economy; Keynes therefore considered a credit-financed government spending programme (deficit spending) necessary to stimulate demand and investment.

According to Keynes, deflation is particularly damaging because consumers and businesses assumed that wages and prices would fall even further based on the observation of falling wages and prices. This led to consumption and investment being put on hold. Normally, low interest rates would have sent an investment signal. However, since people expected that falling wages and profits would increase the real debt burden over time, they refrained from consumption or investment (savings paradox).

Concrete economic policy recommendations

Keynes, like Friedrich August von Hayek, had foreseen an economic crisis. Hayek, however, based on the theory of the Austrian School, had regarded the 1920s as a period of (credit) inflation. The theoretically based expectation was that prices should have fallen due to increased production efficiency. Consequently, Hayek advocated contractionary monetary policy by the Federal Reserve to initiate a mild deflation and recession that would restore equilibrium prices. His opponent Keynes disagreed. In July 1928, he stated that while there were speculative bubbles in the stock market, the key indicator of inflation was the commodity index and it did not indicate inflation. In October 1928, in light of several increases in the discount rate by the Federal Reserve, Keynes warned that the risk of deflation was greater than that of inflation. He stated that a prolonged period of high interest rates could lead to a depression. The speculative bubbles on Wall Street would only mask a general tendency for businesses to underinvest. According to Keynes' analysis, the prolonged period of high interest rates led to more money being saved or invested in purely speculative assets and less money flowing into business investment because some prices such as wages, rents and rents had little downward flexibility, consequently high interest rates would initially only reduce business profits. In response to the deflation that actually set in a little later, Keynes advocated moving off the gold standard to allow for expansionary monetary policy. Keynes' monetary policy analysis gradually prevailed, but his fiscal policy analysis remained unused during the Great Depression.

Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz (Monetarism)

→ Main article: Monetarism

For a long time after 1945, Keynes' explanation determined the interpretation of the Great Depression. In the 1970s, monetarism became the dominant explanatory model. Like John Maynard Keynes, monetarism attributes the global economic crisis to the restrictive policies of central banks and thus to misguided monetary policy. According to this view, however, it is not aggregate demand but the regulation of the money supply that is the most important variable for controlling the course of the economy. Unlike Keynesians, they therefore consider monetary policy to be sufficient and reject deficit spending.

The most detailed monetarist analysis is A Monetary History of the United States (1963) by Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz, which blames the Federal Reserve for making the Depression so deep and long. Among the mistakes made was that the FED

- accepted the contraction of the money supply (deflation) from 1929 to 1931, which was mainly caused by the banking crisis, without taking action, and

- in addition, the high interest rate policy of October 1931, and

- the high interest rate policy from June 1936 to January 1937.

According to this, the numerous bank failures between 1930 and 1932 destabilised the economy because, on the one hand, customers lost a large part of the money they had invested and because the banks' function of creating money on a collective basis was significantly disrupted. This led to a 30% reduction in the money supply in the US between the years 1930 and 1932 ("great contraction"), triggering deflation. In this situation, the Federal Reserve should have stabilized the banks, but did not. The monetarist view of the Great Depression is overwhelmingly considered correct, but some economists consider it insufficient on its own to explain the severity of the depression.

Common position of Keynesianism and monetarism

From the perspective of today's dominant schools of economics, governments should strive to keep the interrelated macroeconomic aggregates of money supply and/or aggregate demand on a stable growth path. During a depression, the central bank is supposed to provide liquidity to the banking system and the government is supposed to cut taxes and increase spending to keep the nominal money supply and aggregate demand from collapsing.

In 1929-32, during the slide into the Great Depression, the US government under President Herbert Hoover and the Federal Reserve (Fed) did not. According to a popular view, the disastrous effect was that some Fed decision makers were influenced by the liquidation thesis. President Hoover wrote in his memoirs:

"The leave-it-alone liquidationists headed by Secretary of the Treasury Mellon ... felt that government must keep its hands off and let the slump liquidate itself. Mr. Mellon had only one formula: 'Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate' ... 'It will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up the wrecks from less competent people.'"

"The leave-the-economy-to-liquidate-itself were led by Treasury minister Andrew Mellon [... They] believed that the government should stay out of it and let the economic downturn unwind itself. Mr Mellon kept saying 'wind down jobs, wind down capital, wind down farmers, sell off property [...]. That will flush the rot out of the system. High costs of living and high standards of living will adjust. People will work harder and live more moral lives. Values will adjust and enterprising people will take over the ruins left by less competent people.'"

Between 1929 and 1933, the liquidation thesis was the dominant economic policy idea worldwide. Many public policy makers (e.g. Reich Chancellor Heinrich Brüning), were substantially influenced by the belief in the liquidation thesis and decided not to actively fight the severe economic crisis.

Before the Keynesian revolution of the 1930s, the liquidation thesis was widespread among contemporary economists and was advocated in particular by Friedrich August von Hayek, Lionel Robbins, Joseph Schumpeter and Seymour Harris. According to this thesis, depression was good medicine. The function of a depression, they argued, was to liquidate bad investments and firms that were operating with outdated technology in order to free the factors of production, capital and labor, from this unproductive use so that they would be available for more productive investment. They pointed to the brief depression of 1920/1921 in the United States and argued that the depression had laid the foundation for the strong economic growth of the later 1920s. Similar to the early 1920s, they advocated deflationary policies at the onset of the Great Depression. They argued that even a large number of corporate bankruptcies should be accepted. Government intervention to mitigate the depression would only delay the necessary adjustment of the economy and increase social costs. Schumpeter wrote that

"... leads us to believe that recovery is sound only if it does come of itself. For any revival which is merely due to artificial stimulus leaves part of the work of depressions undone and adds, to an undigested remnant of maladjustment, new maladjustment of its own which has to be liquidated in turn, thus threatening business with another [worse] crisis ahead."

"we are of the opinion that economic recovery is sound only when it comes of itself. Any revival of the economy based merely on artificial stimulation leaves some of the work of the depression undone and leads to further aberrations, new aberrations of its own kind, which in turn must be liquidated and this threatens to plunge the economy into another, [worse] crisis."

Contrary to the liquidation thesis, not only was economic capital redeployed during the Great Depression, but a large portion of economic capital was lost in the early years of the Great Depression. According to a study by Olivier Blanchard and Lawrence Summers, the recession from 1929 to 1933 caused accumulated capital to collapse to pre-1924 levels.

Economists such as John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman believed that the policy recommendation of inaction resulting from the liquidation thesis exacerbated the Great Depression. Keynes tried to discredit the liquidation thesis by describing Hayek, Robbins and Schumpeter as "[...] austere and puritanical souls who regard the [Great Depression ...] as an inevitable and desirable nemesis to economic 'over-expansion' - as they call it [...]. It would be, in their view, a victory for the mammon of injustice if so much prosperity were not subsequently offset by general bankruptcies. They say that we need - as they politely put it - a 'prolonged liquidation period' to get back to square one. Liquidation, they tell us, is not yet complete. But in time it will be. And when sufficient time has passed to complete the liquidation, all will be well again [...]".

Milton Friedman recalled that such "dangerous nonsense" was never taught at the University of Chicago and that he could well understand why at Harvard - where such nonsense was taught - bright young economists turned away from their teachers' macroeconomics and became Keynesians. He wrote:

"I think the Austrian business-cycle theory has done the world a great deal of harm. If you go back to the 1930s, which is a key point, here you had the Austrians sitting in London, Hayek and Lionel Robbins, and saying you just have to let the bottom drop out of the world. You've just got to let it cure itself. You can't do anything about it. You will only make it worse. ... I think by encouraging that kind of do-nothing policy both in Britain and in the United States, they did harm."

"I think the Austrian School's overinvestment theory has done serious damage to the world. If you go back to the 1930s, which was a crucial time, you see the proponents of the Austrian School - Hayek and Lionel Robbins - sitting in London saying that you had to let things break. You had to leave it to heal itself. You can't do anything about it. Anything you do will only make it worse. [...] I think that by encouraging inaction they have done harm both in England and in the United States."

Recent developments

Debt deflation

→ Main article: Debt deflation

Building on the purely monetary explanation of Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz and on The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions (1933) by Irving Fisher, Ben Bernanke developed the theory of the so-called credit crunch due to debt deflation in 1983 as a non-monetary (real economic) extension of the monetarist explanation.

The starting point is Irving Fisher's observation that a fall in prices (deflation) leads to falling nominal incomes. Since the nominal amount of debt and interest owed remains unchanged, this leads to an increase in the real debt burden. This can lead to a debt deflationary spiral: the increase in real debt burden causes some debtors to become insolvent. This leads to a reduction in aggregate demand and thus to a further reduction in prices (worsening deflation). This, in turn, leads to even further falls in nominal incomes and thus to an even greater increase in the real debt burden. This leads to further insolvencies and so on.

Ben Bernanke expanded the theory to include the "credit view." When a borrower becomes insolvent, the bank has the collateral auctioned off. But deflation also causes the prices of tangible assets, real estate, etc. to fall. This causes banks to reconsider the risks of lending and consequently lend less. This leads to a credit crunch, which in turn leads to a reduction in aggregate demand and thus to a further reduction in prices (exacerbation of deflation).

There is strong empirical validity that debt deflation was a major cause of the Great Depression. Almost every industrialized nation experienced a period of deflation between 1929 and 1933, when wholesale prices fell by 30% or more.

Reflationary policies are recommended as a solution to the debt deflation problem.

The importance of expectations

An impressive extension of the monetarist view and the debt deflation effect is the additional modelling of expectations. The background to the extension is that rational expectations have increasingly found their way into economic models since the 1980s and have been part of the mainstream of economics since the widespread consensus for the new neoclassical synthesis. Thomas Sargent (1983), Peter Temin and Barry Wigmore (1990), and Gauti B. Eggertsson (2008) see the expectations of economic agents as a major factor in the end of the Great Depression. The assumption of office by Franklin D. Roosevelt in March 1933 marked a clear turning point for American economic indicators. The consumer price index had indicated deflation since 1929, but turned to mild inflation in March 1933. Monthly industrial production, which had been falling steadily since 1929, showed a turnaround in March 1933. A similar picture is seen in the stock market. There is no monetary reason for the March 1933 turning point. The money supply had fallen unabated up to and including March 1933. There had been no cut in interest rates, nor was there likely to be, since short-term interest rates were near zero anyway. What had changed were the expectations of businessmen and consumers, for Roosevelt had announced in February the abandonment of several dogmas: the gold standard would be effectively abandoned, a balanced budget would no longer be sought in times of crisis, and the restriction to minimal government would be abandoned. This caused a change in the expectations of the population: instead of deflation and a further economic contraction, people now expected moderate inflation, through which the real burden of nominal interest rates had to fall, and economic expansion. The change in expectations led entrepreneurs to invest more and consumers to consume more.

A comparable change in political dogma also took place in many other countries. Peter Temin sees a similar, albeit weaker, effect, for example, in the change in the German Reich government from Heinrich Brüning to Franz von Papen in May 1932. The end of Brüning's deflationary policy, the expectation of Papen's economic policy, albeit a small-volume one, and the successes at the Lausanne Conference (1932) brought about a turning point in the economic data of the German Reich.

The hypothesis explicitly does not contradict the analysis of Friedman/Schwartz (or Keynes) that a monetary policy appropriate to the situation could have prevented the recession from sliding into a depression. In the Great Depression, however, with nominal interest rates near zero, the limit of pure monetary policy had been reached. Only a change in expectations could restore the effectiveness of monetary policy. In this respect, Peter Temin, Barry Wigmore, and Gauti B. Eggertsson (contrary to Milton Friedman) certainly also see a positive effect of Roosevelt's (moderately) expansionary fiscal policy, albeit predominantly on a psychological level.

In 1937, a moderate tightening of monetary policy by the US Federal Reserve and a moderate tightening of fiscal policy by Roosevelt took place in the USA, motivated by the economic boom of 1933-1936. This caused the recession of 1937-38, in which gross domestic product declined more than the money supply. According to a study by Eggertsson/Pugsley, this recession is largely explained by a (mistaken) change in expectations to the effect that the policy dogmas from the period before March 1933 would be restored.

International crisis export through the gold standard and protectionism

Gold standard

→ Main article: Gold standard

Some countries did not experience a full-blown banking crisis, but were nevertheless hit by deflation, a sharp decline in industrial production and a sharp rise in unemployment. In these countries, the near-unanimous view is that the gold standard acted as a transmission mechanism, spreading the U.S. deflation and economic crisis around the world. Because of the gold standard in place at the time in the United States, many European countries, and parts of South America, central banks were required to hoard so much gold that any citizen could exchange their paper money for an equivalent amount of gold at any time.

- In the 1920s, many economies lost gold and foreign exchange due to large current account deficits in foreign trade with the US. This was offset on the capital account side by an inflow of gold and foreign exchange due to large loans from the US.

- At the turn of the year 1928/1929, the US Federal Reserve switched to a policy of high interest rates in order to dampen the economy. The high interest rates in the USA meant that creditors preferred to invest their money in the USA and no longer lent money to other countries. In France, too, a restrictive monetary policy led to gold inflows. While much gold flowed into the US and France, the uncompensated outflow of gold and foreign exchange from some countries in Europe and South America threatened to render the gold standard there implausible. These countries were forced either to abandon the gold standard or to defend it by an even more drastic high interest rate policy and a drastic cut in public spending (austerity policy). This led to recession and deflation. The resulting worldwide contraction of the money supply was the impetus that triggered the Great Depression beginning in 1929.

- The Great Depression was exacerbated by debt deflation and the severe banking crises of the early 1930s, which led to credit crunches and mass corporate failures. To combat the banking crisis, especially the bank runs, the central bank should have provided liquidity to the banks. For such a policy, however, the gold standard posed an insurmountable obstacle. Unilateral economic policy measures to combat deflation and the economic crisis also proved impossible under the gold standard. Initiatives to expand the money supply and/or to pursue countercyclical fiscal policy (reflation) in Britain (1930), the United States (1932), Belgium (1934), and France (1934-35) failed because the measures caused a deficit in the current account (and thus a gold outflow), which would have jeopardized the gold standard.

- Over time, this was seen as a mistake in monetary policy. Gradually, all countries suspended the gold standard and switched to a reflationary policy. According to almost unanimous opinion, there is a clear connection in time and substance between the worldwide departure from the gold standard and the beginning of the economic recovery.

Protectionism

As a result of the Great Depression, many countries switched to a protectionist tariff policy. Here the USA made a start with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 17 June 1930, which resulted in a wave of similar tariff increases in partner countries. Other countries resisted these protective tariffs by trying to improve their terms of trade in other ways: The German Reich, which depended on an active balance of trade to be able to pay its reparations, pursued a crisis-exacerbating deflationary policy from 1930 to 1932; the United Kingdom triggered the currency war of the 1930s in September 1931 by decoupling sterling from gold; the result was the end of the world monetary system that had been in force until then. All these measures provoked ever new attempts by the partners to improve their balance of trade. According to the economic historian Charles P. Kindleberger, all states acted according to the principle: Beggar thy neighbour - "ruin thy neighbour as thyself". This vicious circle of protectionism contributed to a considerable contraction of world trade and severely delayed economic recovery (see also the competition paradox).

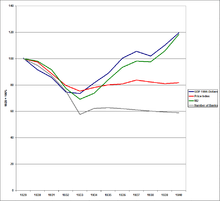

Effects of monetary policy in the US from 1929 to 1940. Real GDP in 1996 dollars (blue), price index (red), M2 money supply (green) and number of banks (grey) are shown. All data have been adjusted to 1929 = 100%. The contraction of the M2 money supply from 1929 to 1933 with a simultaneously falling price index (deflation) is, according to monetarist analysis, a consequence of the banking crisis and an excessively restrictive monetary policy of the FED and the main cause of the Great Depression.

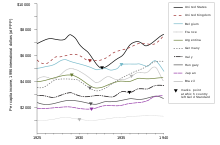

M2 money supply of the U.S. from 1900 to 1942. Between 1929 and 1933, the money supply declined sharply.

.png)

Classic competitive paradoxes in the 1930s

There is a clear link between the abandonment of the gold standard and the start of the economic recovery. Countries that abandoned the gold standard early on (such as the UK or Brazil) experienced only a relatively mild recession.

Unemployed migrant workers (hoboes) jump on a freight train to look for work in other cities

The ratio of private and government debt to US gross domestic product rose sharply during the Great Depression.

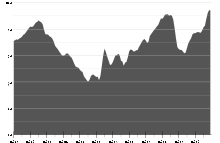

Industrial Production Index of the USA 1928-1939

Comparison with the global economic crisis from 2007

The global economic crisis that began in 2007 was preceded by a long period in which there were no major economic fluctuations (the period is called the Great Moderation). During this period, economists and policymakers overlooked the need to adapt to change the institutions created in the 1930s to avoid another crisis. Thus, a shadow banking system had emerged that evaded banking regulation. Deposit insurance was limited to $100,000 and this was not nearly enough to cushion the financial crisis that began in 2007. In a short-sighted parallel to the banking crisis beginning in 1929, the U.S. government and the Federal Reserve believed that the investment bank Lehman Brothers could be allowed to go bust because it was not a commercial bank and thus there was no danger that unsettled bank customers could plunge other commercial banks into liquidity difficulties in a bank run. Indeed, there was no bank run by "ordinary bank customers." However, the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers triggered a bank run by institutional investors whose deposits had exceeded the volume of deposit insurance many times over. This bank run then quickly spread to the entire international financial system.

After the consequences of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy had shattered the international financial system, governments and central banks reacted to the global economic crisis from 2007 onwards in a way that showed they had learned from the mistakes made during the Great Depression from 1929 onwards. In an internationally coordinated effort, governments increased government spending and cut taxes. Central banks provided liquidity to the financial system. Although the global economy experienced a severe recession and high unemployment, the peak level of the Great Depression from 1929 was avoided.

In 2007, the US and Europe also had a progressive tax system and a social security system that, unlike in 1929, was much larger in volume and therefore acted as an automatic stabilizer to stabilize the economy.

Questions and Answers

Q: What caused the Great Depression?

A: The Great Depression was caused by a crash in the U.S. stock market in 1929, as well as increased taxes on American citizens and increased tariffs on countries that traded with the United States. Economist Milton Friedman also suggested that it was worsened because the Federal Reserve printed out less money than usual.

Q: When did the Great Depression start?

A: The Great Depression started after the U.S. stock market crash in 1929, although many people think it started on October 29th, which is known as Black Tuesday.

Q: Who was president of the United States when the Great Depression began?

A: Herbert Hoover was president of the United States when the Great Depression began in 1929.

Q: How did Roosevelt help during this time?

A: President Franklin D Roosevelt got the government to pass many new laws and programs to help people who were hurt by the Great Depression, such as Social Security and Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). These programs provided income for those affected and put young men to work outdoors with free food and shelter.

Q: What ended wealth from The Roaring Twenties?

A: The prices on Wall Street falling drastically from October 24-29th, 1929 ended wealth from The Roaring Twenties due to many people losing their jobs or becoming homeless and poor afterwards.

Q: How did World War II end The Great Depression?

A: Between 1939-1944 more people had jobs again because of World War II, which helped bring an end to The Great Depression.

Search within the encyclopedia