Gothic architecture

![]()

This article explains the Gothic style of art and architecture. For other meanings of gothic see ibid.

Gothic refers to an epoch of European architecture and art of the Middle Ages, which in its various national manifestations of the early, high and late Gothic period extends temporally approximately from the middle of the 12th century to around 1500. The previously predominant style of building and art is known as Romanesque, the subsequent as Renaissance.

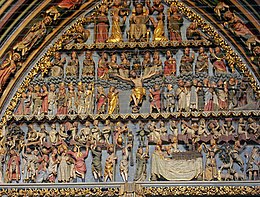

Initially spread by Giorgio Vasari as a pejorative description of architecture, the term gradually established itself in the course of the 19th century also for painting and sculpture, which were created at the same time. Gothic architecture originated around 1140 in Île-de-France (Paris and its environs) and lasted north of the Alps until the first half of the 16th century. The Gothic style can only be precisely defined in architecture, while this is not possible with the same clarity in the fields of sculpture and painting. The most outstanding artistic creation is the Gothic cathedral, which unites architecture, sculpture and (glass) painting of the Middle Ages as a total work of art. It stands at the beginning of a new design of the church interior, which became apparent through the first unification of Burgundian (pointed arch) and Norman formal elements (ribbed vault) and the further development of innovative building measures. In addition, secular architecture also experienced its first flowering, especially in the urban environment: in addition to aristocratic residences, town halls and the burghers' houses, which are rarely preserved in their original condition, are particularly important building tasks.

In architecture, a distinction is made between the phases of early, high and late Gothic, which were adopted at different times in the various European artistic landscapes and then developed further, sometimes independently of each other. In England, for example, one speaks of the Early English Style, the Decorated Style and the Perpendicular Style. In France, a distinction is made between the early Gothic Gothique primitif (1130-1180), the mature Gothique classique (1180-1230), then the refined Gothique rayonnant, followed by the late Gothic Style flamboyant. Brick Gothic is not only found in the north of Germany.

In the post-Gothic period, the Gothic architectural style lived on outside its epoch and can even be traced in the Baroque period as Baroque Gothic as a hybrid between Baroque and Gothic. In the 19th century, the architectural style of neo-Gothic found new interest as a variety of historicism.

Beauvais Cathedral, "outstanding" Gothic style

Evolution of the style name

The style and the new building technique developed in France were called opus francigenum around 1280. In the 20th century, the term French style or French style can again be found in specialist literature. Since the pointed arch is considered a central element of Gothic architecture, the style was originally called the pointed arch style. The modern term Gothic (from Italian gotico "strange, barbaric," originally a swear word derived from the name of the Germanic tribe the Goths) was coined during the Renaissance by the Italian art theorist Giorgio Vasari, who used it to express his disdain for Gothic art compared to the golden age of antiquity. Although Vasari's assessment is no longer shared today, this designation was adopted, gradually became commonplace, and later lost its negative connotation. Vasari is also said to have coined the term "maniera tedesca" (German manner), which was commonly used during the Renaissance.

In Germany, a new enthusiasm for the Gothic began with Goethe's text "Von Deutscher Baukunst" (On German Architecture), printed in 1773, which declared it to be the German style. The misunderstanding that the Gothic originated in Germany was only cleared up by art historical research in the mid to late 19th century. In Germany, as in many other countries, the Gothic was regarded as a national style in the 19th century, which led, among other things, to a positive re-evaluation of medieval art, which had been despised until then.

First Gothic choir gallery of the former monastery church of Saint-Denis, before 1144

Historical foundations in the 12th and 13th centuries

The 12th and 13th centuries were marked by an intellectual, theological, political, economic and technical upheaval. The demands on church building therefore changed:

- As in the Romanesque period, church buildings were demonstrations of the power of the rulers and the clergy. Alongside the power of the king and the bishops, the influence of religious orders such as the Cistercians grew in France in the 12th century. In addition, various large lay movements, such as the Cathars, emerged as competitors to the official church. But also the strengthening of the cities led to "buildings of power" in the middle of the city. In this competitive situation, the king, the monarchically oriented nobility, cathedral chapters, bishops and cities tried to outdo each other with ever more magnificent buildings - as a demonstration of their claim to leadership, but also out of genuine pious enthusiasm.

- At the beginning of the era began a period of general restructuring in the economic life of the country. The economy developed positively in certain regions and in the cities. The focus of trade shifted from the countryside to the city. The rural population flocked to the cities (rural exodus). In France, the economic basis was the strengthening of the French royalty in the 12th century at the expense of the lower nobility and the economic strengthening of the flourishing burgher towns promoted by the kings. It was the cities that developed the strength to finance and realize the elaborate buildings of the Gothic period. The growth of the cities also created a need for new church buildings.

- Gothic architecture was able to draw on the foundations of technically developed architecture and the craftsmanship of the Romanesque period. Ribbed vaults, pointed arches and buttresses had already been successfully introduced in the Romanesque period and Romanesque buildings were increasingly built higher and with greater exposure. The further development of the building trade created the conditions for being able to build the increasingly sophisticated and complex Gothic architecture on a very large scale.

- In theological terms, churches were understood as a built part of the liturgy. They pointed to the New Jerusalem. According to Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis, the cathedral of Saint-Denis was to become the new temple of Solomon. Durandus of Mende († 1296) wrote: "All that belongs to the ecclesiastical services, things and ornaments (ornamenta) are full of divine signs and mysteries." Church buildings, like the cosmos, were to become a perfect unity: beautiful, harmonious, and clear through light, geometry, proportion, material, and color. In the Romanesque period, there were relatively small window openings and large wall surfaces. In the Gothic period, the wall surfaces were increasingly dissolved and replaced on a large scale by glass windows, which from the inside looked like translucent "glass walls" and became an essential design element of church architecture. The rays of the sun, the light of God, were to encompass the entire church and transform the building into a constructed metaphysics. In France, this light architecture developed to perfection from Saint-Denis (from 1130/35) to ChartresCathedral (1194-1260) and the Sainte-Chapelle (1244-1248) in Paris.

Origin of the style

From the Romanesque to the Gothic

The Gothic style developed in the Middle Ages from the Romanesque style. Many individual elements of the Gothic system can already be found in the Romanesque period, especially in Normandy, in the French crown lands of the Île-de-France, in Burgundy and in Norman Sicily. The ambulatory existed in the Romanesque period as early as the 11th century; it was further developed in the Gothic period with the ambulatory and chapel crown into a coherent system of supports and vaults. The first double-towered western facades were built at about the same time in Normandy and Burgundy. But it was not until the construction of the Gothic cross-ribbed vault with load-bearing ribs succeeded that a new building system was able to develop which allowed vault cuts over a wide variety of ground plans and an extensive breaking through of the wall. The Gothic period did not create any fundamentally new building types. However, in the course of its development, the Gothic building was increasingly understood as a unit in which each individual part depended on the whole. Thus, the Gothic period developed its own architectural system as well as a number of new architectural elements. However, even in the case of large hall churches of all phases of the Gothic period, not all elements of Gothic basilicas were adopted. Even more so in the case of village churches and secular buildings, stylistic elements that had become fashionable were used, but not the entire system from the perfect precursor buildings.

Norman forerunners

The most important step towards the Gothic pointed-arched ribbed vault can be seen as a series of Norman basilicas that were donated by William the Conqueror or had ecclesiastical dignitaries appointed by him as builders. These include the abbey church of Lessay, the men's abbey of Saint-Étienne and the ladies' abbey of Sainte-Trinité in Caen (both donated c.1060), and Durham Cathedral in northern England. All have Romanesque portals and windows. In all of them at least the nave has ribbed vaults and two-layered clerestory masonry. In the continental churches these ribbed vaults are round-arched. In Durham alone, built from 1093, the vaults are pointed-arched. The first pointed-arch vaults had previously existed in individual chapels of small Norman churches in England, but it was decades before vaults replaced the wooden ceilings of the central aisles in other English cathedrals.

The first lancet windows and lancet portals of Christian buildings were built at the same time in another area of Europe, but also under Norman rule. They are, from 1071, works of Norman-Arab-Byzantine architecture in Norman-dominated southern Italy.

Burgundian Late Romanesque

In Burgundy, beginning with the third basilica of the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, built from 1088 onwards, a number of sophisticated basilicas were built with Romanesque façades but pointed vaults and arcaded arches. However, the pointed vaults of the central naves and transept arms and the pointed groined vaults of the side aisles did not yet have ribs.

At the start of construction of Cluny III, most of the Arabonormannic architecture had not yet been built, but there was still Arabic architecture in Sicily, which over time was rebuilt or replaced under the rule of the Normans (for example, in Palermo, the summer palace of the emir became a Norman royal palace). As the Latin monastic orders sought to regain a foothold in Sicily, which was then dominated by Orthodox monasteries, monks traveled to Sicily (and back again). Thus Ansgerius, the founding bishop of the Latin diocese of Catania, was a Benedictine from Normandy called to Sicily in 1091.

The abbey church "Cluny III", was provided with buttresses out of necessity until 1130, i.e. ten years before the construction of the abbey church Saint-Denis began, after the first central nave here had collapsed.

The beginnings in France

The first Gothic church building is generally considered to be the former abbey church of Saint-Denis in Paris. The abbey, which was directly subordinate to the king, was the burial place of the French royal house and already occupied a special position in the Romanesque period. Under Abbot Suger, the west building with its double-towered façade was erected in 1137-1140, and from 1140 onwards the ambulatory with its large windows, chapel crown, buttresses and ribbed vaults, which combined all the architectural elements into a unified space. With the simultaneous construction of Sens Cathedral (from 1140), a rapid development of early Gothic began. Examples include the gallery basilicas of the cathedrals of Senlis (from 1153), Laon (from 1155) and Noyon (from c. 1157) and, as a high point, Notre Dame de Paris (from 1163). The recipe for success in the development of the style was that each large building summarized what had been achieved before it and at the same time became the basis for subsequent buildings.

According to another view, the early Gothic period is only considered a preliminary stage, and the "real" Gothic period begins with the High Gothic period at the end of the 12th century. The High Gothic begins with the three "classical" cathedrals of Chartres (from 1194), Rheims (from 1211) and Amiens (from 1218) as three-nave basilicas with ambulatory, three-storey wall elevation, tracery windows and double tower facade.

·

Cathedral (former abbey church) Saint-Denis, before 1140 (modified in the 18th and 19th centuries)

·

Notre-Dame de Chartres, façade, portals around 1150, rose and left tower from 1194 onwards

·

Notre-Dame de Chartres, north portal

·

Double tower facade of Notre-Dame de Paris, 1190-1250

·

High Gothic façade of Amiens Cathedral, portals 1220-1230, rose window and towers 1375-1402

Development outside France

Outside of France, Gothic architecture was first adopted in England, beginning as the true English Gothic (Early English) with the construction of Wells Cathedral in 1180. Again and again, Gothic architectural forms were also exported to neighbouring French countries through monastery foundations by the Cistercians, who came from France, before the Gothic style had become generally accepted there.

In the Roman-German Empire, the Romanesque style initially remained the predominant style. However, Limburg Cathedral, built in the 11th century, was modernized after 1180 on the model of the French early Gothic, and the interior was modelled on Laon Cathedral. The collegiate church of Lilienfeld (Cistercian, from 1202) and Magdeburg Cathedral (from 1209) show that the new French style was aspired to, but that it was still necessary to feel one's way into it. The Capella Speciosa in Klosterneuburg (1222) can no longer be examined, as it was demolished in 1799. From 1224 onwards, Bremen Cathedral was vaulted and redesigned in a Gothic style, without, however, removing the Romanesque arcades. New Gothic buildings were erected from 1230 onwards: the Liebfrauenkirche in Trier and from c. 1230 onwards the Abbey Church of St. Mauritius in Tholey. The present construction of Paderborn Cathedral was begun in 1210 as a Romanesque basilica, but after completion of the first two bays it was continued from 1231 by other builders as a Gothic hall church. The Elisabethkirche in Marburg was built as a Gothic hall church from 1235 onwards. With the Cologne Cathedral, begun in 1248, Germany caught up with the French High Gothic style. Six years later, work began on Utrecht Cathedral in the same style. In the Netherlands, this stone Gothic was not without competition. At the same time, brick Gothic also spread there. There is even visible brick on the tower of Utrecht Cathedral.

In Flanders, the transitional style is called Scheldt Gothic. Later, the splendid Brabant Gothic spread northwards here. The brick Gothic of Flanders did not have an early Romanesque Gothic phase. Finally, the Kempian Gothic combined brick building with the stonemasonry culture of the Brabant Gothic.

The spread of Gothic forms in church building in Italy, where many features of French cathedral Gothic were abandoned, can be traced back to mendicant orders such as the Franciscans and Dominicans. Gothic forms were used extensively in secular architecture in Italy, for example in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena.

In Spain, experts from northern France were brought in to introduce the Gothic style. This is why many Gothic churches in Spain are closer to the architecture of the French crown land than buildings in southern France, where the more angular Gothic méridional developed. In addition, in Aragon and Old Castile, Muslim craftsmen combined Gothic inspiration with Oriental traditions to create the Gotico-Mudéjar style.

Considerable departures from the programme of French cathedral Gothic are to be found in rural and small-town churches in all regions of Europe, including France itself.

Building

From the Romanesque to the Gothic basilica

The Gothic period did not create a fundamentally new building typology, but it did further develop the previous forms into an architectural system of its own.

The original form of the Romanesque church building was based on the Roman secular basilica. The elements atrium, porch, west work and tower or side towers, nave with or without side aisles, transept, main apse, possibly side apses and choir (rarely with ambulatory) as well as double choirs in the east and west added up to a complex spatial structure; one speaks of the additive principle in the Romanesque.

In the Gothic period, porches are rarely built, and the Romanesque elements of atrium and west choir are dispensed with altogether. West works in their original form are no longer built, but Gothic second-tower facades can either open up the view to the roof ridge of the nave, as in Reims Cathedral and St. Mary's Church (Lübeck), or still form high crossbeams, as in Strasbourg Cathedral and Magdeburg Cathedral. A compromise is found at Notre-Dame de Paris, where a tracery arcade between the second uppermost tower storeys provides a view of the roof ridge.

·

Lübeck's Marian towers, seen from the ridge turret of the nave.

·

Magdeburg Cathedral: The gable of the west building towers far above the nave.

·

Strasbourg Cathedral: magnificent facade with horizontal launch, tower a little later.

·

Rostock's Marienkirche: late decision for a central tower, on the left the choir of the transept.

Gothic churches usually have a choir only in the east. However, this can be very large. While Romanesque choirs are rarely more than one or two bays long, Gothic ones are sometimes longer than the nave. Whereas in Romanesque churches the choir usually ends with a gable adjoined by a semicircular apse, which may be much lower, Gothic choirs often end in a polygon, around which a choir ambulatory may still be led. In England and parts of northern Germany, however, rectangular choir ends predominate, in Gothic times without apse. In many churches originally built in Romanesque style the apse was removed in Gothic times. Individual Gothic cruciform basilicas have a Greek cross as their ground plan. There, the very large and long transept may also have a choir.

Floor plan

As in the Romanesque period, the most common ground plan was the simple long building with transept. The early Gothic churches still follow the bound system, in which a square central nave bay with a six-part vault is assigned two bays in each side aisle. As a Gothic church without a transept, the three-aisled cathedral of Sens (1140-1160) with a simple ambulatory without side chapels stood at the beginning. As directional buildings followed, for example, the cathedral of Senlis (from 1153) as a three-storey, three-aisled gallery basilica. The cruciform cathedral of Laon (from 1155), on the other hand, has a wide projecting transept and, as a special feature, a rectangular choir plan in the English tradition. Particularly high-ranking buildings were emphasized by a five-nave ground plan, as in the early Gothic gallery basilica of Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral (from 1163) or the High Gothic basilica of Bourges (from about 1195).

In the High Gothic period, the bound system was abandoned in favor of transverse rectangular nave aisles. The pattern for the "classical" French cathedral, the basilica with a three-nave nave and projecting transept, double-towered façade and ambulatory with chapels, was set by the High Gothic buildings of Chartres (from 1194), Rheims (from 1211) and Amiens (from 1218). In the course of the development of increasingly complicated vaulting forms, the rhythmic bays of hall churches in particular became less and less important, and the central and side aisles, crossing and choir were able to merge into a unified space.

·

Ground plan of the cathedral of Sens early gothic three-aisled basilica (from 1140/45) with later added transept

·

Bonded system of the early Gothic cathedral of Laon (1155-1235)

·

Floor plan of the High Gothic cathedral of Chartres with transverse rectangular nave vaults (from 1194)

· ![]()

Floor plan of Freiburg Cathedral with High Gothic nave and Late Gothic choir

· ![]()

Ground plan of Canterbury Cathedral with early Gothic choir and late Gothic west longhouse

Development of the choral sector

The Gothic architecture brought considerable changes to the choir area. The choir ambulatory, already known in the Romanesque period, with a chapel ring of attached chapels was combined by the Gothic period with the ribbed vaulting to form a uniform space, in which in the course of development the chapels can also largely merge with the ambulatory. Compared to the relatively small choir areas of Romanesque churches, the Gothic choir area is considerably extended in length and width, which can also be multi-aisled and have double ambulatories. In some cases, the row of chapels is also continued along the long choir, which made it possible to install a large number of altars. At the same time, the extended choirs provided space for the installation of large choir stalls for a large number of canons.

The crypts that were often built in the Romanesque period, which raised the floor of the choir considerably, are generally dispensed with in Gothic churches. The only slightly raised choir was often separated from the lay room by rood screens. As a new element, the pulpit, which originated in the preaching churches of the mendicant orders, found its way into the church interior in the 13th century. Another creation of the Gothic period is the sacrament house as a small piece of architecture.

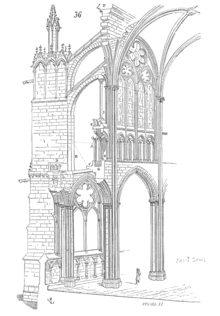

The towers

The church towers were intended to proclaim the claim to power of their builders. In the Gothic period, this claim was pushed to the limits of what was technically possible: higher, lighter and more organic, as part of the overall building. Many of the world's tallest church towers date from the Gothic period or from later completions of Gothic buildings.

The building type of multi-towered basilicas still originates from the Romanesque period (e.g. Bamberg, Naumburg, Limburg), but became a discontinued model in the early Gothic period, as for example in the three-aisled cathedral of Laon with its five towers. Originally, seven towers were planned here: two west towers, two on each of the transept facades and a crossing tower. Reims Cathedral was also to have seven towers, but only three were realized. In Chartres even nine towers were planned, but were not built.

The double-tower façade is the almost "classic" type of French Gothic cathedral (bishop's church), which could also be used for important collegiate or abbey churches. The façade with the towers was intended to fit organically into the overall Gothic building, and so the two towers stand in front of or above the side aisles; the central nave lies between them. The facades, which were often richly decorated, could also have large portals and sometimes very extensive sculptural cycles. Double-towered facades are found, for example, in the cathedrals of Paris, Rheims and Amiens or the Elisabethkirche in Marburg. A variant with towers standing to the side of the aisles is offered by the English cathedral of Wells. In the Middle Ages, Gothic double-towered facades often remained unfinished, were given different towers, as in Chartres and Bourges, or remained with a single tower, as in Strasbourg. Several buildings were not completed until the 19th century, such as Cologne Cathedral, which, with its huge double-tower façade, is considered the third-highest church building in the world.

Gothic parish churches were usually given only a main tower or a single-tower façade, but in the German and Dutch-Flemish Gothic - supported by the emerging bourgeoisie of the cities - could sometimes compete with the dimensions of the largest cathedrals (bishop's churches). One architecturally outstanding example is Freiburg Cathedral, whose 116-metre-high west tower dominates the façade. After this tower was completed, a competition between the cities began. Individual towers were built in Landshut, Frankfurt am Main, Hamburg and Delft, for example. The Ulm Minster Tower, at 161.53 metres the highest church tower in the world, was not completed until the 19th century, as were quite a few Gothic church towers in Central Europe. A special case is the 136.67-metre-high south tower (1359-1433) of St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna, which was built as a choir flank tower to the side of the nave. Its position is not so rare in southern Central Europe: the cathedral in Donauwörth has a flank tower, as do many parish churches south of the Danube. In Italy, west towers were the exception at all times. An example of a west tower completed in the Middle Ages in the middle of the nave of a cathedral is the Utrecht Cathedral. There, however, the nave collapsed in a hurricane in 1674 and was not rebuilt.

Single towers as crossing towers can be found e.g. at the cathedrals of Salisbury and Beauvais, whose almost 150 m high late Gothic crossing tower, however, collapsed again after only 4 years.

Construction and style

General features

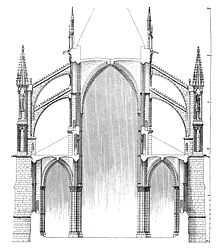

A central feature of Gothic architecture is the extensive use of windows to break through the outer wall surfaces and the reduction of wall thicknesses and vault masses to a minimum. In order to achieve this, the construction elements already known in the Romanesque period, such as ribbed vaults, pointed arches and buttresses, were consistently developed into a new system in which design and structural concerns were combined. The constructive system of the Gothic period developed the principle of ancient architecture of support and load considerably further.

The decisive innovation of the Gothic construction consisted in shifting the load-bearing elements of the construction to a large extent to the exterior, so that towards the interior it became possible to relieve and break through the walls to a large extent, which could now be filled with glass windows and made the entire interior appear light and seemingly weightless. At the same time, the lighter Gothic construction made it possible to erect ever taller buildings.

An important technical innovation from the 13th century onwards is the use of tie rods and ring anchors made of iron, which can be used to stiffen and stabilise the statics of parts of buildings and the entire building structures. For the increasingly large tracery of the windows, iron bars also become an integral part of the window construction.

Basilica

The principle of static equilibrium is established in the basilica form of construction in that the lateral shear forces of the vaults are diverted to the buttresses on the outside of the building and balanced out by the compressive forces applied. In the three-nave basilica, a lower side-nave bay is assigned to each side of a central nave bay. Above the central nave bay rests an ogival cross-ribbed vault, whose diagonal ribs are supported by the central nave piers, which absorb the downward thrust of the vault. The outward thrust of the vault is transmitted via the buttresses formed by buttress arches across the side aisle vaults to buttresses which absorb the lateral thrust. The stability of the buttresses can be increased by masonry superimposed loads, which counteract the thrust by their mass.

Another way of absorbing or reducing the vault thrust acting on the outside of the building is to install tie rods or tie beams under the base of the vault from one side of the wall to the other, which is particularly common in hall churches, where there is no buttressing.

On the walls of the clerestory and side aisle, the vault stretched between the piers of a yoke is caught by a pointed arch that serves as a relief arch. This allows the side wall between the supporting skeleton of the piers to be completely pierced and filled with windows. A high point of this development is reached in the High Gothic, where large tracery windows take up almost the entire wall surface of the clerestory and the rear wall of the triforium below is additionally pierced with windows. The first time a translucent triforium is found is around 1231 in the cathedral of Saint-Denis.

Hall churches

→ Main article: Hall church

A special form of Gothic church building is the hall church. In contrast to the basilica, here all side aisles have the same height, so that the nave resembles a huge hall. However, the model for this was not provided by Île-de-France, but by the Angevin Empire, which existed in western and northern France from 1128 to 1204, where hall churches had previously been built in the Romanesque style in Poitou, with barrel vaults. Now, as an alternative to the pointed ribbed vault, the domical vault was developed as a likewise pointed ribbed vault. In the cathedral of Poitiers and some other buildings, halls of naves of the same height were built with domical vaults, which corresponded to the aesthetics of the emerging Gothic style. Probably due to the exile of Henry the Lion and Bernhard zur Lippe there, it became a model for the construction of hall churches in Germany.

Poitiers Cathedral is strictly speaking a staggered hall, its central nave thus slightly higher than the side aisles. Between the cross-section of the staggered hall and the basilica lies that of the pseudo-basilica, here the imposts of the central nave vaults are at or above the apex height of the side nave vaults. In Spain, conversely, basilicas were created with the cross-section of staggered halls, in which small windows of the central nave are located above the apexes of the side nave vaults, which are only slightly lower. The form of the individual vault bays and the question of basilica or hall church were not firmly coupled: in the German late Romanesque period several basilicas were built with cathedral vaults but still Romanesque windows and portals, and many if not most Gothic hall churches received groined vaults.

Hall churches manage with considerably less external buttressing than basilicas, and even without any if stabilized by a row of chapels. And naves of equal height made innovative vault constructions possible, from the choir polygon supported by a central column ("palmier") in the two-aisled Jacobin church in Toulouse (1230) to the dissolution of the yoke boundaries in the St.-Annen church in Annaberg-Buchholz (1499-1525).

Although the hall church type was particularly popular in Germany, it is also found in other countries. Probably the highest hall nave built in the Middle Ages is that of the Frauenkirche in Munich at 37 metres. The vaults of the Jacobin Church in Toulouse and those of the Marienkirche in Gdansk have a height of 29 metres. In particular, but by no means exclusively, city parish churches were often realized as halls or staggered halls. Pseudo-basilicas were sometimes created by extending single-nave churches or by simplification.

Romanesque basilicas were often subsequently converted into Gothic hall churches. Two-aisled hall churches were built regionally, especially in Austria, and in terms of purpose especially as religious churches. One of the largest is the Franciscan/Jacobean church in Toulouse (choir completed around 1290, nave around 1330).

Double aisles are not usually counted as halls. Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral and Cologne Cathedral have five aisles along their entire length. The double ambulatory of Reims Cathedral provided space for the coronation ceremonies of French kings. The double side aisles of Augsburg Cathedral were built in the course of the extension of the originally Romanesque nave. In the case of Ulm Cathedral, which was planned with three naves, the threat of collapse was averted by dividing the side aisles lengthwise. Among the five-aisled Gothic basilicas, only in Milan Cathedral are the outer aisles lower than the inner aisles.

·

Cathedral of Poitiers, from 1166, is considered the model of the German hall churches

· .jpg)

Herford Minster 1220-1250, partly Romanesque walls, Gothic vaults

·

Hall nave of St. Sebald in Nuremberg

·

St. Maria zur Wiese in Soest, before 1421, piers without fighters

·

Central nave of St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna, 1st half 15th century

·

Reims Cathedral: double ambulatory, no hall choir

·

Cathedral in Verden (Aller), hall choir as of 1290

·

Jacobean church in Toulouse, choir around 1290

·

St. Sebald in Nuremberg, choir as of 1361

·

Schwäbisch Gmünd Minster, from 1330, vaults around 1500

·

Church of Our Lady in Pirna, from 1502

Individual elements of Gothic architecture

Ribbed vault

Cross ribbed vaults were already built in the Roman Empire. The first cross ribbed vaults originated in Norman architecture, in England even from the beginning with pointed belt arches. The oldest are yokes in the side aisles of Durham Cathedral, from 1098 onwards, which at that time had only round arches apart from these belt arches. The innovation was that in the vault with a quadrangular plan, two round arches were placed crosswise over the two diagonals, usually with a decorative keystone at the intersection. This improved the stability of the vault, and the vaulting shells could be thinner and thus lighter. The belt and shield arches above the four outer sides were built pointedly upwards and could thus be given the same height as the two longer and higher round arches above the diagonals. However, in most ribbed vaults, the apexes of the vault quarters rise from the outer sides towards the central keystone. The ribs allowed for any number of intermediate shapes between a cross vault and a domed vault (domical vault). During construction, the vault caps between the cross ribs could now be freely bricked up without having to create a full casing. It is not uncommon for the ribs to be pointed-arched as well. It became possible to create a vault bay over a rectangular floor plan, rather than just a square floor plan as in Romanesque groined vaulting. As the style developed further, more complex and intricate forms were also created, such as reticulated vaults. The use of vault ribs remained characteristic of the style.

Pointed arch

The pointed arch is considered a central element of Gothic architecture, which was therefore formerly also referred to as the "pointed arch style". Although pointed arches are already known as a single element from the Romanesque period, the use of round arches still prevailed there. The pointed arch is constructively an approximation of the arch form, which corresponds to the favourable static force course of a parabola. Pointed arches determine the appearance of Gothic buildings and are found practically universally in the cross-section of all vaults, in the form of window and portal jambs, and in the tracery. Keel arches are a late Gothic pointed arch variant, which, however, is only possible with iron anchors; the convexity of the upper arch sections contradicts the basic principle of vaulting. In Gothic secular architecture, cross-storey windows with rectangular jambs without pointed arches were also common. Furthermore, as in the preceding and subsequent styles, segmental arches were built. The basket arch was a new addition.

Longwall

→ Main article: Longwall

The buttress is another central structural and design element of the increasingly tall church buildings. It is composed of buttresses and buttress arches and, in the case of a basilica, serves to absorb the lateral thrust of the vault and the wind load from the central nave and high choir. The stability of the buttresses is increased by superimposed loads, which can be designed as decorative elements such as pinnacles. Drains for rainwater and melt water were also integrated into the buttress, which shot away from the building via gargoyles in the arch and was thus kept away from the masonry and foundations. While in the early Gothic period the flying buttress had mainly a static function, it later developed into an important architectural element and is clearly emphasised. However, the choir and nave of Magdeburg Cathedral, the first Gothic-designed basilica in Germany, manage without flying buttresses, and since the side aisles carry free-standing transverse roofs, there are no hidden flying buttresses either.

Resolution of the wall

The Romanesque period is still characterised by a massive, fortress-like construction of wall and building, in which the thickness of the wall is often still deliberately emphasised. In the Gothic period, the lighter construction method with pointed arches, ribbed vaults, buttresses and buttresses made it possible to shift the load-bearing elements to the exterior, to greatly reduce the thickness of the walls and to largely break through the walls with windows. The static function of the structural elements is deliberately masked in the interior in order to create an illusion of lightness and weightlessness in the architecture.

In the interior, a walkway known as a triforium is let into the wall above the arcades to the side aisles and choir gallery, so that an "inner" and "outer" wall shell is created. However, this double shell is already found in the Norman basilicas. Notre-Dame de Dijon in Burgundy offers an exemplary example of Gothic double-shell wall construction. A large number of large windows were set into the outer wall, making the building appear light and flooded with light. Finally, in the High Gothic period, the rear wall of the triforium is also windowed, so that the wall appears completely open. Nevertheless, practically every element of a Gothic building is load-bearing. Gothic builders created new constructions by evolutionary development according to the principle of "trial and error". This is why some buildings collapsed during the construction phase or had to be subsequently reinforced with additional force-dissipating elements due to cracks that occurred.

Emphasis on the vertical

This stylistic feature is particularly pronounced in the French Gothic. As a climax, the vaults of Beauvais Cathedral reached a vertex height of 48.5 m; Cologne Cathedral, for example, has 45 m. In comparison, the vault apex of the Romanesque cathedral at Speyer has a height of only 33 m. The height increased in proportion to the width. In the Romanesque period, this ratio is, for example, 1:1.9 for St. Michael in Hildesheim and 1:2.5 for the Speyer I section of the Speyer Cathedral. A leap then took place in the Gothic period. The width/height ratio in the cathedral of Reims is 1:3 and in the cathedral of Amiens 1:3.3. In the English Gothic period, great room heights with emphasized verticals were dispensed with and the length of the building was increased in relation to the width.

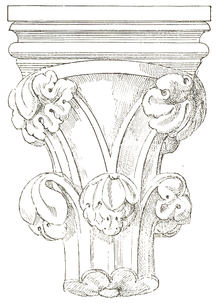

Pillars and capitals

In the Romanesque period, the wall elevation still follows the ancient principle of "support and load", in which the round-arched arcades are supported by columns whose capitals are based on a block as the basic form and are often richly decorated with figures, ornaments or plant motifs.

In the Gothic period, these antique columns are replaced by slender structured round pillars, which are often surrounded by services or carry further services themselves. The early Gothic bud capitals now have a cup-like basic form and are usually only decorated with plant motifs. An increasing number of accompanying services led to the development of the bundle pillar, in which the capital recedes further and further until, in the late Gothic period, the forms merge and the capital disappears completely as an architectural element, which means a complete departure from ancient building principles.

A special form of pillar arrangement in Gothic churches is the so-called single-pillar room.

Tracery and other decorative elements

→ Main article: Tracery

·

early gothic windows still without tracery: Noyon, from 1150 onwards

·

early gothic windows still without tracery: Magdeburg Cathedral, from 1209 onwards

· .jpg)

Windows at Herford Minster,

from left to right: Romanesque, late Gothic, early Gothic, late Gothic

·

Brick Gothic with ashlar tracery: Bruges Cathedral, Late Gothic

·

Iron tracery since time immemorial: Windows of St. Mary's Church in Gdansk, late Gothic

·

Tracery made of fired clay: Katharinenkirche in Brandenburg

The tracery is a typical building ornament of the High and Late Gothic, which is developed from geometric shapes, such as circles and arches. It can be executed in ashlar or brick and is used in the arched field of windows, but also on parapets and wall surfaces. The invention of tracery is also known as the "birth of Gothic proper" and first appears around 1215/20 at Reims Cathedral. In addition to lancet-arched tracery windows, circular rose windows can also be found, which in the Gothic period can be increased to dimensions up to the width of the façade. Finally, in the late Gothic period, more intricate and complicated tracery forms were developed in a variety of fish-bubble and flame patterns (flamboyant). The models for many Gothic ornaments came from the plant world. Oak leaves played a special role. The tops of gables and towers were often ornamented with a finial or pinnacle (compare also Wimperg).

Builders and master builders

Owner

The builder of an episcopal church was the chapter as landlord (see Domkapitel, Stiftskapitel) and not the bishop. The construction of collegiate and monastic churches was initiated by the abbot or abbess and determined or influenced financially and also in terms of content by the patron. Chapter and bishop or city and city parish priest agreed on the organization for the construction of an episcopal or parish church in various ways and appointed, as for example in Narbonne for the construction of the cathedral of Narbonne, two canons and two clerics each as administrators for a limited period. Builders were also called ecclesiastics, procurators, magister fabrice, magister operis, operarius, or even architectus.

The royal family, the urban bourgeoisie, the monarchically oriented nobility, the church chapter and to some extent also the bishops supported the new style.

Opposed to this were the leading classes of the feudal nobility with their estates, threatened with relegation, who saw in the Gothic cathedrals manifestations of a new power hostile to them. Also opposed were those monastic orders whose position of power in the countryside was endangered, at first thus the Cistercians, later - after 1220 - above all the new mendicant orders of the Dominicans and Franciscans, who often made themselves the mouthpiece of the urban lower classes - and of course the heretic movements were also against the new splendid architecture. In Paris, therefore, there were serious conflicts between the cathedral clergy and the scholars of these aforementioned orders teaching at the university: Thomas Aquinas, Bonaventure of Bagnoregio, and Albertus Magnus. And all these orders then also formed other building concepts for their churches, which represent, so to speak, architectural models against the Gothic cathedrals.

Even among the proponents of the Gothic there was discord due to competition and prestige. The bishops and the nobility wanted to manifest their power with the cathedrals. The up-and-coming citizens of the cities, however, also wanted to make their pious contribution. But the clergy and nobility did not tolerate this. They rejected the donations of the citizens, because the work of the cathedral should be their merit alone. There were even uprisings of the citizens about this, who wanted to force their contribution. Later on, citizens built churches named after them as a demonstration of their own power against the bishop, often close to the cathedral. In doing so, they tried to outdo the cathedral.

Builder

The leaders of the construction were often called wercmeistere (master craftsmen) or master builders; they mostly came from the stonemasonry trade and were the medieval architects. Designations such as magister operis also occurred. In execution the master stonemason (magister lapicidae) and the master mason (magister caementari) as well as the sculptor were important. The masters of construction changed more frequently with each building, if only because of the long construction times.

Some important cathedral builders or master builders and stonemasons of the Gothic period became famous:

- at Cologne Cathedral as Cologne Cathedral master builders, in particular Master Gerhard († 1271), Master Arnold († 1308), John of Cologne, Master Michael († after 1387), Master Andreas von Everdingen († before 1412), Nikolaus van Bueren (1380-1445), Konrad Kuene van der Hallen (1400/10-1469)

- at St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna in particular Michael Knab (1340/50- after 1399), Wenzel Parler (before 1360-1404), Hans Puchsbaum (1390-after 1454), Laurenz Spenning (1400/10-1477), Anton Pilgram (1460-1515), Jörg Öchsl (around 1500)

- the Roriczer dynasty of master builders at Regensburg Cathedral, whose members occupied the position of cathedral master builder from 1415 to 1514 at the latest - beginning with the master Wenczlaw (before 1415-1419), who came from Bohemia, through Konrad Roriczer (1456- around 1476), to the brothers Matthäus (1476-1495) and Wolfgang Roriczer (1495-1514).

- William of Sens, master builder around 1175 at Canterbury Cathedral and before that at Sens Cathedral

- Master craftsman Guerin of the Cathedral of St. Denis (13th century)

- Master craftsman Hugues Libergier (1229-1263) from the abbey church of St-Nicaise in Reims.

- Master craftsman Pierre de Montreuil (c. 1250) of Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral

- The Parler family of master builders, including Heinrich Parler the Elder (1300/1310-1370), Michael Parler (c. 1330-1390), Johann the Younger (c. 1359-1405) and Johann the Elder, worked on the cathedrals of Basel, Freiburg, Gmünd, Strasbourg and Ulm, as well as St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague and St. Barbara's Cathedral in Kutná Hora; the name Parler gave rise to the term foreman.

The masters could often be identified by their stonemason's mark, a common mark in the Middle Ages that they placed on their work.

Regional dissemination and further development

In architecture, a distinction is made between early, high and late Gothic, which developed differently in the various regions:

| Early Gothic | High Gothic | Late Gothic | |

| France | 1140–1200 | 1200–1350 | 1350–1520 |

| England | 1170–1250 | 1250–1350 | 1350-ca. 1550 |

| Italy | since 1200 | ||

| Holy Roman Empire | 1220–1250 | 1250–1350 | 1350-ca. 1520/30 |

As the Renaissance spread north, east and west of the Alps in the early 16th century, the Gothic style quickly lost influence.

Regional style terms

In addition to the general chronological distinction between early, high and late Gothic, some special terms are used for certain regional style characteristics or building techniques:

- Rayonnant, French for radiant, stands for the High Gothic style phase from ca. 1230 to 1350 with maximum large window areas and translucent triforium. In the tracery, the window roses are divided into radially radiating courses, as in the rose windows of Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral.

- Flamboyant is the term used to describe the last stylistic stage of the late Gothic period in France, Flanders and England.

- The Decorated Style (also Decorated Period) is a phase in English Gothic architecture that lasted from 1250 to 1370.

- The Perpendicular Style is a typical style of the late Gothic period in England.

- Brick Gothic refers to the implementation of the Gothic style with the building material brick, from the 13th to the 16th century as North German Brick Gothic in northern Germany and the Baltic region widespread, but without this additional designation also in other regions (see below the section on brick Gothic).

- As a term, the German Sondergothic is a controversial, ideologized style level designation of the Gothic period of the 14th and 15th centuries in Germany.

- The Chiaramonte style is a Gothic architectural style of the 14th century in Sicily.

- Post-Gothic is the term used to describe the continuation of the Gothic architectural style after its actual epoch in the Renaissance period and also still in the Baroque period.

- Neo-Gothic or Neo-Gothic is one of the earliest styles of historicism in the 19th century. Its dependent formal language was oriented on an idealized image of the medieval of the Gothic.

France

Around the beginning of the 13th century, the episcopal churches of Chartres (from 1194), Rheims (from 1211) and Amiens (from 1218) developed the "classical" French cathedral as a three-aisled basilica with a gallery, three-storey wall elevation with triforium, double tower façade and tracery windows. The large-scale building of Bourges Cathedral (from 1195), on the threshold of the High Gothic period, also brought some innovations, but remained unique in its form as a five-nave basilica without transepts. The dissolution of the wall reached a climax in Burgundy with the double-shell wall construction, as in the cathedrals of Lausanne (now Switzerland, from 1190) and Auxerre (from 1215) or the parish church of Notre-Dame in Dijon (from 1230).

The High Gothic phase begins with the introduction of tracery windows around 1215/20 in the choir of Reims Cathedral. With wall surfaces largely broken up by windows, the fenestration of the triforium (for the first time around 1230 on the nave of St.-Denis and in Amiens) and the radiating tracery of the window rosettes, the High Gothic Rayonnant style was created around 1230. New standards were set by the cathedral of Amiens, which was still largely completed in the 13th century, with a nave height of 42.30 metres. The striving for size and maximization of window areas culminated in the cathedral of Beauvais, begun in 1247, which surpassed Amiens with a choir of over 46 m nave height, but whose vaults partially collapsed as early as 1287. The Gothic gigantism was not finished in Beauvais, however, until 1569, when an approximately 150 m high crossing tower was added on top of the repaired choir, which also collapsed after four years. Apart from the choir and the transepts, the church was never completed.

In addition to the sometimes huge cathedrals, large monastery churches were built, as well as thousands of parish churches and chapels such as the famous Sainte-Chapelle in Paris (1244-1248), whose vaults seem to float on luminous "glass walls".

Some art historians place the precursors of the French late Gothic as early as around 1300. There was no further significant development in the building types, the scheme of the "Cathedral Gothic" was rather simplified. The Hundred Years' War (1337-1453) with England brought building activity largely to a halt after the first third of the 15th century. A major new cathedral was only begun in Nantes in 1434, but numerous large parish churches were built for the rapidly growing city population after the end of the war. However, many interrupted large buildings were also continued and finished. Since most of the large churches were built for centuries, many buildings also show elements of the various Gothic eras. One did not slavishly adhere to the original plans, but continued to work in the current style.

From around 1350, the late Gothic flamboyant style came to the fore as a decorative style, which takes its name from the flame-shaped tracery and ornamental forms that often cover huge areas. Some large buildings were now finished off with magnificent west facades, and transept facades were also built in the Flamboyant style. An early Flamboyant building is the abbey church of Saint-Ouen in Rouen (from 1318). Other examples include the Basilica of Notre-Dame de L'Épine (from c. 1405), the Abbey Church of Vendôme, the Chapel of Brou (from 1513) or the transepts of Senlis Cathedral (16th century).

The deep roots of the Gothic style in France can be seen in its continuation in the post-Gothic period, which still produced buildings such as the Cathedral of Orléans (from 1601) or Saint Eustache in Paris (1532-1649) in the Renaissance period.

· Early Gothic in France and Germany

· ,_cathédrale_Notre-Dame,_croisillon_sud,_tribunes_côté_est_2.jpg)

Gallery of the Laon Cathedral 1155-1235

·

gallery of the Limburg Cathedral, (ca. 1190) -1235

Germany

In the period of the French early Gothic, only one significant work of this style was begun in Germany, the Gothic reconstruction of Limburg Cathedral from about 1180. The first large Gothic building begun, Magdeburg Cathedral (from 1207/1209), already falls into the period of the French High Gothic, but still shows clearly early Gothic features in its oldest parts, the ambulatory has the cross-section of a gallery basilica and without tracery pointed arch windows. In contrast to most Gothic basilicas, Magdeburg Cathedral has no flying buttresses, a feature that was adopted by some neighbouring buildings to the east. It was not until the end of the High Middle Ages that the Gothic style became generally accepted in Germany. However, in several churches of the late Romanesque period, the traditional overall proportions and the round-arched portals and windows were retained, but the statically advantageous innovation of the pointed-arched ribbed vaulting was adopted for the ceilings. The central building of the Liebfrauenkirche in Trier (from c. 1230), the abbey church of St. Mauritius in Tholey (from c. 1230) and the hall church of the Elisabethkirche in Marburg (from 1235) are readily regarded as the first purely Gothic church buildings on present-day German territory. Closely related to the Elisabethkirche is the early Gothic Cistercian monastery church of Haina, which may also predate the Marburg church. The choir of the Wetzlar Cathedral and the nave of the Freiburg Minster were also begun as Gothic reconstruction projects around 1230. In the case of Freiburg Cathedral, Gothic forms may have been mediated by the Cistercian monastery church of Tennenbach, the chronological position of which, however, has not been clarified. At Paderborn Cathedral, whose two western bays still correspond to the concept of a Romanesque basilica, Gothic construction continued from 1231 onwards, although not according to the pattern of the Île de France, but according to the pattern of Poitiers Cathedral.

Following the pattern of French cathedral Gothic, the High Gothic nave of Strasbourg Cathedral was built in 1245-1275, followed by its large-scale west façade from 1277, which is on a par with the best achievements of French master builders. Although Strasbourg now belongs to France, it is historically a major work of German High Gothic architecture. It was followed in 1248 by the cathedral building of Cologne Cathedral, which, with a five-aisle plan and immense dimensions, attempted to surpass its model of Amiens Cathedral. In the Middle Ages, the cathedral was not even half completed and could only be finished in the 19th century according to the original plans as one of the largest churches in the world. The St. Mary's Church in Lübeck, built between 1250 and 1350, is hardly less ambitious. It was designed as a parish church in the form of a French cathedral and to demonstrate its supremacy over the bishop's church in Lübeck through its size and height. Through its adaptation to the local building material of brick, St. Mary's Church also became the initial building of the Brick Gothic style for northern Germany and the Baltic region. Around 1260, the reconstruction of Halberstadt Cathedral began according to the Reims model, of which initially only three nave bays could be realized; the rest of the construction took until around 1500. The Regensburg Cathedral, modelled on St-Urbain in Troyes, was the only building in Bavaria to be built according to the French cathedral scheme, and was begun around 1285/90.

In addition to the large episcopal churches, numerous parish churches were quickly built in the cities, which sometimes reached or even exceeded the dimensions of the cathedral buildings. In Freiburg im Breisgau, the cathedral was an early major work of German Gothic architecture, whose main tower with its openwork helmet, completed around 1330, became the model for many later tower solutions and was one of the few large Gothic towers to be completed in the Middle Ages. From 1377 onwards, Ulm Cathedral reached even greater dimensions, but its main tower, the tallest in the world, was not completed until the 19th century. As a monastery church, the Cistercian monastery church of Altenberg, begun in 1259, stands out. Without towers and with reduced architectural decoration, it expresses Cistercian "modesty", but its dimensions are impressive.

From the early Gothic (rebuilding of Limburg Cathedral on the model of Laon Cathedral) to the late Gothic, the German or Central European Gothic had a wide range between close imitation of French models (St. Barbara in Kutná Hora, Bohemia, 1388-1588) and its own ideas. The German preference for hall churches was hardly shared in the Rhineland, and in the southwestern Baltic cities from Lübeck to Stralsund at least one large basilica with flying buttresses was built in each case - in brick. For deviations from the model of Capetian France, including the abandonment of the ambulatory and chapel crown, there is the term "reduction Gothic". The term "German Special Gothic" is outdated.

The hall enabled the development of elaborate vaulting systems, in which the demarcation of the individual bays receded further and further, merging into a unified space and often spanned by magnificent net or loop ribbed vaults (Annaberg, Freiberg). Especially the late Gothic period created significant examples here. The southern German imperial cities, especially Nuremberg and Regensburg, and the Hanseatic cities on the Baltic coast, especially Lübeck and Stralsund, developed into local centres of Gothic architecture.

For a long time, especially in the 19th century, Gothic was considered a typically German style. After the wars of liberation against Napoleon, Gothic architecture was transfigured into the epitome of an original German, Christian, medieval world order. This romantic dream image was elevated to a positive counter-image. Cologne Cathedral, which was not yet completed at the time, became the architectural epitome of German greatness, and at the same time Gothic architecture was reinterpreted as a German style. At the height of the glorification of the German Gothic, Franz Theodor Kugler was the first to publicly state that the home territory of the Gothic was northern France.

·

Strasbourg Cathedral, a major work of German High Gothic architecture, from 1245, north tower completed 1439.

·

Cologne Cathedral, general view of the west facade completed in the 19th century

·

West facade of the Altenberg Cathedral, from 1259

·

Regensburg Cathedral of St. Peter, the only cathedral of French scheme in Bavaria, from 1273.

·

Nuremberg Church of Our Lady, from 1350.

·

Ulm Cathedral, from 1377, with the highest church tower in the world, since 1890.

England

English Gothic cathedrals often have two transepts in the east and a straight chancel end. The choir was greatly lengthened, and instead of an apse, a Lady Chapel was often added. What is remarkable about the exterior of the cathedrals are the wide west facades. It is also striking that the crossing tower often towers above the main towers. Another peculiarity of English Gothic is the special emphasis on length in contrast to the more obvious striving for height on the Continent. The English buildings were almost without exception built with three naves. No effort was made to increase the area by double aisles or side chapels; instead there were extreme length-to-width ratios. The abbey church of St. Albans and Winchester Cathedral reach lengths of about 170 m.

On the island, from about 1175 onwards, "modern" continental architectural forms were adopted, which combined with the native Anglo-Norman tradition (Norman Style) to form the Early English Period (1175-1260) and were brought to the country in particular by the Cistercian Order. Among the stylistic features of the Early English Style, which is very sparse, is the ribbed vaulting. In the 13th century, the development of more complicated vaulting forms (star vaulting) and more decorative patterns of ribs (e.g. apex ribs) began. The first English Gothic building is considered to be the choir of Canterbury Cathedral, built between 1175 and 1184 by William of Sens.

During the Decorated Style (1250-1370), hardly any wall surface was without tracery veneering; the vault ribs also join together to form richer patterns (star or net vaults). The pointed arch becomes the ogee arch. The raised clerestory allows for the installation of larger, colored windows, thus brightening the interior. Examples of the Decorated Style can be found in Westminster Abbey in London (choir, begun 1246) and in the cathedrals of York (c. 1290-1340) and Wells (c. 1290-1340). A masterpiece is the crossing octagon of Ely Cathedral, built between 1321 and 1353, with its lantern terminating the tower.

The Perpendicular Style (1330-1560) (Latin perpendiculum: perpendicular, guide) took back the ornamentation of the Decorated Style in favour of a clear, geometric style with an emphasis on widths. The windows became very wide, often covering the entire east side, and were given a very shallow pointed arch, the Tudor arch, which developed because normal pointed arches would have found no place with the new dimensions of the windows. The fan vault occurs.

The new style was first realized in Gloucester Cathedral (choir, cloister with fan vault, 1337-1357). Other examples include Winchester Cathedral (nave, begun 1394), King's College Chapel in Cambridge (begun 1446), and Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey (1503-1519). Perpendicular style building continued in England for over 200 years, well beyond the end of the Middle Ages. As late as 1640, for example, the staircase of Christ Church College in Oxford was built with a fan vault. The Tudor Style blended the Perpendicular Style with Renaissance forms. England is the only European country in which the Gothic style never completely died out, but continued to exist in part in the countryside and were taken up again in the Gothic Revival.

·

Canterbury Cathedral

·

Salisbury Cathedral

·

The typical layout of the English cathedral based on Salisbury Cathedral.

·

rood screen in the gothic cathedral of Bristol

·

The situation in Ireland is similar: Early Gothic Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin

Italy

In the Italian architecture of the Middle Ages, which remained strongly oriented to the ancient models, there is a direct development from the Romanesque, sometimes called the Proto-Renaissance, to the Early Renaissance (Quattrocento) in the early 15th century. The Gothic architectural style, in the French or Central European style, was not completely adopted in Italy, nor was it ever dominant on its own.

The Italian Gothic style shows its own characteristics, which lack many of the features of the French Cathedral Gothic. As a rule, they avoided rooms with a pronounced upward thrust, large openings in the walls with large tracery windows, open buttresses, rich architectural decoration, large figural portals, and double-towered facades. Italy preferred clear and straight building forms with large, often richly painted wall surfaces, as well as lower and often wide rooms. The exterior buildings made of typical building materials such as marble and brick are often kept very simple except for the façade.

The Cistercians imported Gothic architectural forms into Italy for the first time with the abbey churches of Fossanova (1187-1208), the cross-rib-vaulted monastery church of Casamari (1203-1217) and the abbey of San Galgano (from 1224). Under the influence of Cistercian architecture, the mendicant orders introduced Italian Gothic and mendicant architecture with the construction of the Gothic upper church of San Francesco in Assisi. The architectural sculpture was reduced to the most necessary, and the extensive walls were decorated with extensive fresco cycles. The church buildings of the Franciscans and Dominicans were often in competition with each other, such as the Franciscan Frari Church and the Dominican San Zanipolo in Venice. This did not lead, as in France, to ever new heightening of a uniform concept, but to self-expression through originality.

In Siena, the Romanesque cathedral was gothicized from the early 13th century. Particularly noteworthy here is Giovanni Pisano's three-portal west façade (from 1284), which probably draws on French models. Another prominent building is the Romanesque-Byzantine basilica of St. Anthony in Padua.

From 1387 onwards, the Milan Cathedral was built, which, as an exception, was strongly oriented towards the Central European Gothic style. The interior of the huge, 157 m long five-aisled building is reminiscent of Bourges Cathedral but also of local Romanesque models (Piacenza Cathedral). The city lord Gian Galeazzo Visconti wanted to manifest the power and influence of his city and his family through one of the largest cathedrals in Europe. Its Gothic construction and decoration met with great resistance from the local population and bitter controversies arose among the master builders. Heinrich Parler, for example, withdrew from the building business in a huff after his proposal to raise the central nave was rejected as too "un-Italian". As a rival building to Milan, the five-nave Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna was built from 1390 onwards, also in huge dimensions of 132 m in length and 45 m vault height, whose simple, clearly structured interior is once again typical of Italian Gothic architecture.

The municipal palaces of the Italian city republics, some of which were fortress-like and often had a high belfry, competed with the church buildings. Important Gothic secular buildings include the Palazzo Vecchio (1299-1314) and the Loggia dei Lanzi (1376-1382) in Florence, the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena (1297-1310) and the Doge's Palace (from 1340) in Venice.

· _-_Facade.jpg)

Padua: Basilica of St. Anthony, from 1290

·

Sta-Maria della Spina in Pisa, from 1323

·

Five-nave nave of the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna

·

Palazzo Pubblico of Siena

Netherlands and Belgium

Starting from Tournai and using limestone from the Tournai area, a transitional Romanesque-Gothic style developed in Flanders, which was then still a French fiefdom, the Scheldt Gothic style, whose influence extended as far as northern Germany.

The choir of Utrecht Cathedral was built from 1254 onwards by the same master builders as that of Cologne Cathedral (from 1248 onwards), and accordingly bears a very close resemblance. The western parts of Utrecht Cathedral (the nave of which collapsed in a hurricane in 1674 and was subsequently demolished piece by piece) are built with a brick core, which also forms the outer skin of two chapels and parts of the tower.

In the course of the Gothic period, in Flanders and almost the entire area of today's Netherlands, domestic stone imported from more southerly regions, especially tuff from the Eifel, was increasingly replaced by brick, the use of which there, a little later than in northern Germany, had already begun in the Romanesque period. The Count's Palace in the Binnenhof in The Hague, the ruling centre of the County of Holland, is one of the most important works of Dutch brick construction. The Romanesque eastern part ("Rolzaal") was built around 1250, the early Gothic knights' hall 1280-1295, i.e. at the time when the construction of the Prussian Marienburg began.

In the late Gothic period, the so-called Brabant Gothic developed in the Duchy of Brabant, which in the church architecture (Herzogenbosch Cathedral, Antwerp Cathedral, Nikolaaskerk in Ghent and Martinkerk in Ypres) dispensed with building elements compared to French models and is therefore called reduction Gothic, but in secular buildings unfolded a splendour hardly known elsewhere. Examples of this are the town halls of Louvain and Mechelen. One of the most important architects was Jehan d'Oisy from Picardy in France. Particularly important churches and town hall façades often follow the Brabant Gothic in material and design, even in places where brick construction had otherwise been adopted. Bruges, in particular, has important works of stone Gothic, but even more numerous works of brick Gothic.

In Germany, Xanten Cathedral is clearly influenced by the Dutch Gothic style; other Lower Rhine buildings are also worthy of mention here (in Kalkar St. Nicolai and several brick houses, built mainly of tuff the Willibrordi Cathedral in Wesel and the Salvatorkirche in Duisburg, mainly of brick the Stiftskirche in Kleve and the Maria-Magdalena-Kirche in Goch). Decorative layers of natural stone, mostly tuff, and brick can be found on numerous buildings, such as the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam and the church Alt St. Martinus in Stommeln near Cologne.

The Meuse Gothic style also developed in the diocese of Liège, which today extends over parts of the Netherlands and Belgium.

·

Knight's Hall in The Hague, ca. 1280

·

Oude Kerk in Delft, South Holland

·

wooden barrel vault of the Oude Kerk in Delft

·

Nieuwe Kerk, Amsterdam, North Holland

·

Grote Kerk in Workum, province of Friesland

·

Choir (from 1254), transept and tower of Utrecht Cathedral

·

Town hall in Culemborg on the Lek, Gelderland

·

St. John's Cathedral in 's-Hertogenbosch, Noord-Brabant

·

Petruskerk in Oirschot, Noord-Brabant

·

Brussels Cathedral, 15th century facade

·

Antwerp Cathedral

·

Church of Our Lady in Bruges, from 1210, stonemasonry according to the French model, tuff, brick

· .jpg)

St. Salvator Cathedral in Bruges from 1280, yellow brick

· .jpg)

Bruges City Hall, 1376-1421

·

Sint-Janshospitaal in Bruges, present parts from 1200 onwards

· .jpg)

Brussels City Hall, 1402-1449

·

City Hall of Leuven, 1439-1468

·

Town hall of Oudenaarde, 1526-1536

Austria

The only Gothic cathedral in Austria is St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna, a large hall with two planned huge choir side towers, of which only the south tower was completed. Important monastic churches with hall choirs are to be found at Heiligenkreuz and Zwettl; large Gothic city parish churches are St Stephen's in Braunau and St Jacob's in Villach. The parish church in Königswiesen and the parish church in Weistrach stand on the border from the late Gothic to the Renaissance and, with their looping ribs, exhibit an almost "baroque" formal dynamic. These two churches were built at the beginning of the 16th century and are characterised by their autonomous vault design.

·

St Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna

·

Pulpit in St. Stephen's Cathedral, Vienna

·

Graz Cathedral

Eastern Europe

In the Gothic sacred architecture of Poland, Bohemia, Moravia, Hungary and other Eastern and East-Central European countries, special local developments mix with basic structures imported from Western Europe and Germany. In the cities and regions dominated by the German bourgeoisie, Central European influences prevailed. Through the trade relations of the Baltic cities, Dutch elements also entered this area; the Church of St. Mary in Gdansk may be cited as an example.

In Bohemia, the great cathedral on Prague's Hradcany remained unfinished until the early 20th century. The high to late Gothic choir of St. Vitus Cathedral was begun by a French master and continued by Peter Parler. In addition to St. Vitus Cathedral, the "Cathedral" of Kutna Hora, dedicated to St. Barbara, is considered a highlight of Bohemian architecture. Nearby Kolín on the Elbe also has an important choir building of the Parler school. In Most (Brüx), the late Gothic deanery church was moved some 800 metres in a spectacular action to save the richly vaulted hall from open-cast lignite mining.

The former Greater and Lesser Poland also has numerous Gothic sacred buildings. Brick dominates as a building material; Cistercian architecture in particular was stylistically influential here for a long time. In the case of the great cathedral (from 1320) on the Wawel in Krakow, these influences are now partly blurred by later alterations. The two-nave, star-vaulted church in Wiślica (c. 1350) refers to models of monastic secular architecture (refectories, chapter rooms).

Krakow's St. Mary's Church was the parish church of the German community in the Middle Ages. The steep brick basilica has an original late Gothic spire crowned by a golden crown. The Poznan Cathedral has a "French" ambulatory chancel; however, due to the devastating destruction of World War II, the building today presents itself mostly as a reconstruction of its original medieval state. Several Gothic churches in Poland, not only those of special orders, have no or only a moderately high bell tower, but representative gables.

·

St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague, from 1344

·

St. Barbara in Kutná Hora (end of the 14th century)

·

Wenceslas Cathedral in Olomouc, 13th-14th c.

·

Elisabeth Cathedral in Košice, 15th c., a middle building between a basilica and a central building

·

St. Martin and St. Nicholas in Bydgoszcz, 1466-1502

·

Church of the Raising of the Cross in Koło, 14th/15th c.

·

Sandomierz Cathedral, around 1360, Baroque gable 1670

·

St. Mary's Church in Gdansk, 1343-1502

· .jpg)

Latin Cathedral of Lviv (Lemberg), Ukraine, 1370-1474

·

Gothic vaults of the Orthodox Cathedral of Vilnius, later remodeled on the outside, from 1346 onwards

The Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) have several larger brick churches of North German or Westphalian style in the old Hanseatic cities of Riga and Reval (Tallinn). However, the magnificent brick façade with elements of the "Flame Gothic" of the Lithuanian St. Anna's Church in Vilnius is far removed from the German models.

In the Slavic parts of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, several partly Catholic, partly Orthodox churches and one or the other castle were built in the first half of the 16th century in a mixture of Gothic, Renaissance and Byzantine elements, also known as White Russian Gothic.

In Romania, the Gothic architectural style had difficulty developing due to its affiliation with the Orthodox cultural sphere. Nevertheless, the Romanian Orthodox Church is the only one among the Orthodox churches that accepted Gothic or Gothic-influenced buildings. Gothic architecture, however, remained mainly confined to Transylvania, which belonged to the Kingdom of Hungary during the Gothic period. The influence of occidental culture on the Romanians can be seen here in the Romanian Orthodox wooden churches of the Maramures and the Apuseni Mountains. Outside the Carpathian arc, the Gothic style can be found in some of the Moldavian monasteries and in isolated churches from Wallachia and Moldavia.

In Transylvania, on the other hand, there are numerous buildings of the German and partly of the Hungarian minority, which were built in the Gothic style. The largest and probably best known of these is the Black Church in Brasov. It is not only the largest Gothic cathedral in southeastern Europe, but also the most southeastern. At the same time, it is the largest cult building between St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna and the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

· Romanian Orthodox churches in Gothic style

·

Putna Monastery in the north of the Vltava

·

Wooden church from Transylvania

·

Wooden church from the Maramures

·

Saint Spiridon Church in Bucharest

· Evangelical Lutheran and Reformed Churches in Transylvania

·

Black Church in Brasov, Transylvania

·

City parish church in Sibiu, Transylvania

·

High Gothic fortified church in Biertan, Transylvania

·

Calvary Church in Cluj-Napoca, Transylvania

In the other predominantly Christian-Orthodox states of Eastern and Southeastern Europe, the Gothic style was unable to develop because of their affiliation with the Orthodox (Byzantine) cultural sphere.

Switzerland

The Swiss Gothic style is naturally oriented towards France in western Switzerland (Lausanne, Geneva). German-speaking Switzerland has three major Gothic sacred buildings in the cathedrals of Basel, Bern and Freiburg im Üechtland (French Fribourg, originally German-speaking). Bern and Fribourg i.Ü., with their single-tower facades, are reminiscent of the cathedral in Fribourg im Breisgau. The cathedral of Basel is Romanesque in essential parts. The high choir was rebuilt in Gothic style after a severe earthquake (1356). The west towers also date from a later period.

·

Lausanne Cathedral, from c. 1170, the most important early Gothic building in Switzerland

·

Former Franciscan church Barfüsserkirche of Basel, after 1298

·

Late Romanesque Basel Minster with Gothic additions, after 1356-1500

· .jpg)

Late Gothic nave of Bern Minster, from 1421

·

Romanesque-Gothic cloister of the Hauterive monastery near Fribourg, 1150-1330

Scandinavia